The Case for Noncompetes

Scholars and other commentators widely assert that enforcement of contractual and other limitations on labor mobility deters innovation. Based on this view, federal and state legislators have taken, and continue to consider, actions to limit the enforcement of covenants not to compete in employment agreements. These actions would discard the centuries-old reasonableness standard that governs the enforcement of these provisions, often termed “noncompetes,” in all but four states (notably, California). We argue that this zero-enforcement position lacks a sound basis in theory or empirics. As a matter of theory, it overlooks the complex effects of contractual limitations on labor mobility in innovation markets. While it is frequently asserted that noncompetes may impede knowledge spillovers that foster innovation, it is frequently overlooked that noncompetes may encourage firms to invest in cultivating intellectual and human capital. As a matter of empirics, we show that two commonly referenced bodies of evidence fail to support zero enforcement. First, we revisit the conventional account of the rise of Silicon Valley and the purported fall of the Boston area as innovation centers, showing that this divergence cannot suitably be explained by differences in state law regarding noncompetes. Second, we show that widely cited empirical studies fail to support a causal relationship between noncompetes, reduced labor mobility, and reduced innovation. Given these theoretical and empirical complexities, we propose an error-cost approach that provides an economic rationale for the common law’s reasonableness approach toward contractual constraints on the circulation of human capital.

Introduction

On February 23, 2017, two titans of Silicon Valley went to war in federal court: Google filed a lawsuit against Uber, accusing it of using intellectual property allegedly stolen by one of the lead engineers on Waymo, Google’s self-driving automotive subsidiary.1 Specifically, Google alleged that Anthony Levandowski had misappropriated Google’s intellectual property before departing (along with other Google engineers) to found Otto, a self-driving car startup subsequently acquired by Uber for $680 million.2 The legal basis for Google’s lawsuit against Uber and Levandowski consisted of a medley of federal trade secret, patent infringement, and state trade secret and unfair competition claims.3 Given the high economic stakes, commentators speculated that if Google prevailed, the ultimate damages could exceed a billion dollars.4 While the litigation was pending, the trial judge ordered Levandowski to stop working on projects involving the technology that had been allegedly misappropriated.5 Although Google and Uber settled the dispute shortly after trial proceedings commenced for a mere $245 million, an arbitration panel subsequently found against Levandowski (who was fired by Uber6 ) and, on an interim basis, awarded Google $127 million in damages, for which Uber may be financially responsible under indemnification obligations to its former employee.7

The Google-Uber litigation, and the rich suite of legal and economic instruments deployed to restrain the departure of a prized employee, is a notable counterexample to the now-standard account of unrestrained employee movement in Silicon Valley, the world’s preeminent innovation cluster. That account emphasizes the ease with which technical and managerial talent, and the intellectual capital embodied in that talent, circulates among competitors, resulting in knowledge spillovers that redound to the collective benefit of the innovation ecosystem. This free-flowing movement of human capital is widely attributed to cultural norms, organizational practices, and, especially among legal scholars, California’s refusal to enforce a contractual clause known as a “covenant not to compete” (or “noncompete”).8

A noncompete typically limits a former employee’s ability to work for competitors in a certain industry and a certain geographic area for a certain period of time. In contemporary scholarly and policy discussions of innovation policy, the noncompete has recently become a surprising focal point. Specifically, the literature has widely adopted the view initially espoused by Professor Ronald Gilson—albeit in a much more qualified form—that California’s general refusal to enforce noncompetes in significant part explains the exceptional growth of Silicon Valley since the early 1980s while Massachusetts’s willingness to enforce noncompetes spurred the purported decline of the Route 128 area around Boston.9 Following this view, California has enjoyed a healthy circulation of human capital, while Massachusetts has been deprived of the “agglomeration economies” that promote robust innovation clusters.10 The result in California is a virtuous circle of accelerated innovation that led to the rise of Silicon Valley; the result in Massachusetts is a sad story of a Silicon Valley that could have been but wasn’t.

The recent surge of interest in noncompetes is a welcome extension of innovation policy analysis. Noncompetes, and the broader universe of contractual and economic restraints on labor mobility, are a critical but overlooked tool in promoting robust innovation ecosystems. Scholarly discussions of innovation policy typically focus on the extent to which intellectual property rights such as patents or copyrights regulate the flow of informational assets. But this misses a key component of any innovation environment—namely, the flow of intellectual capital embedded in the human beings that innovate and commercialize new products and services. In the business world, firms are keenly aware of the value of human capital and use contractual and economic instruments to avoid losing their most valuable personnel to competitors. Based on a survey of 11,500 participants, a recent study found that an estimated 18 percent of all US workers (roughly, 30 million people), and approximately one-third of workers in professional, scientific, and technical occupations, are subject to noncompetes.11 The extent to which the law should enforce these contractual instruments is a matter of fundamental importance.

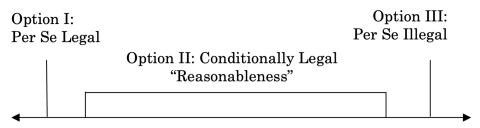

In recent years, a growing number of scholars and policymakers have adopted a simple answer to this question: never.12 Following this view—popularized by the slogan, “talent wants to be free”—the free circulation of human capital always, or usually, promotes innovation. As such, any constraints “imposed” by employers reflect either overreaching or economic irrationality.13 As a matter of policy, this view recommends that all states adopt California’s purported zero-tolerance regime—a change that would undo the common-law “reasonableness” standard currently used by forty-six states to adjudge the enforceability of noncompetes.14 (The current exceptions are California, North Dakota, and Oklahoma, which bar noncompete enforcement against individuals in most circumstances;15 recently, Hawaii barred noncompetes for “technology business[es].”16 ) To be clear, even under the long-standing common law doctrine (dating from an English precedent in 171117 ), noncompete clauses are enforceable only if they set forth “reasonable” temporal, geographic, and scope-of-industry limitations.18 For the “talent wants to be free” school of thought, it seems that no limitation on the movement of talent can ever be deemed reasonable.

These academic views now play a prominent part in ongoing policy debates and press coverage concerning proposed laws that would limit, or bar, the enforcement of noncompetes.19 On March 7, 2019, a bipartisan group of six Democratic and Republican US senators sent a joint letter to the Government Accountability Office requesting that it investigate the impact of noncompetes “on workers and on the economy as a whole.”20 Citing academic research that “California’s ban on non-compete agreements has been a prime factor in the state’s growing economy,” three Democratic US senators introduced legislation in April 2018 to impose a ban on noncompetes nationwide, which was re-introduced by two Democratic and Republican US senators in October 2019.21 Like these US senators, advocates for strict limitations on, or outright bans of, noncompetes explicitly refer to selected empirical studies in arguing that these reforms would facilitate labor mobility and promote innovation.22 A leading academic opponent of noncompetes has written: “[T]he research suggests that noncompetes should be banned for all employees, regardless of skill, industry or wage; they simply do more harm than good.”23 In 2018, the influential Economist magazine endorsed an only slightly more qualified position, arguing that noncompetes should be enforced only in narrow circumstances and similarly referring to academic research to support this position.24

A sizeable number of state legislatures have derived similar conclusions. Since 2014, the legislatures of thirty-seven states have formally considered laws that would affect the enforceability of noncompetes in employment agreements.25 Of those proposed bills, all but six proposed to limit enforceability (up to and including outright bans). In twenty-one states, these debates have translated into action. This includes Massachusetts, which in 2018 enacted a statute prohibiting noncompetes for certain categories of employees26 and, in most other cases, imposes notice obligations on employers.27 The Appendix shows all statutory changes to state noncompete laws during 2014–2019. Nineteen changes reduced enforceability and six enhanced it (although one was repealed two years later and the other was offset by other provisions that limited enforceability). In enacting its ban on noncompetes in the technology industry, Hawaii specifically referenced academic studies that purportedly supported this policy action as being conducive to innovation.28 Additionally, in California, some courts have recently adopted expansive understandings of the state’s statutory limitation on enforcing noncompetes against individuals, applying it to other contractual obligations that have long been thought to lie outside the purview of the statute.29 In 2018, a California lower court even applied the statutory limitation to prevent businesses from entering into exclusivity agreements between themselves, which had been traditionally the purview of California’s antitrust provisions, not its statutory prohibition against noncompetes.30 While the appellate court reversed this ruling, it is nonetheless indicative of an increasingly dogmatic approach against the enforcement of noncompetes or other contractual provisions deemed to have a comparable effect.31

The vigorous political debate and ongoing legislative activity relating to noncompetes encompasses a variety of policy concerns, including efficiency-related economic concerns as well as noneconomic concerns involving personal autonomy and distributive justice.32 In markets for highly skilled technical and managerial labor (as distinguished from lower-income and lower-skilled occupations, which has been the focus of some of the proposed legislative bans33 ), the debate on both sides has principally relied on economic arguments. The toolkit of law-and-economics analysis is well suited to provide a balanced analysis of efficiency-related arguments for and against proposed policy shifts with respect to noncompetes that apply to technical and managerial personnel in technology markets.

In this Article, we undertake that task. Specifically, we look closely and broadly at the economic arguments, both theoretical and empirical, that have been advanced in support of the “talent wants to be free” view. While the details are complex and nuanced, our conclusion is simple and modest. Neither economic theory nor empirical evidence provides compelling support to abandon the common law’s centuries-old reasonableness standard. Contractual restraints on labor mobility in technology markets raise complex trade-offs between employers’ training and R&D incentives (generally favored by noncompetes) and employee mobility (generally disfavored by noncompetes).34 While the latter is important for innovation, so is the former, and case-specific application of the reasonableness standard arguably offers the best, albeit imperfect, mechanism for balancing those competing considerations.

The now-popular view that innovation always or usually does best when human capital circulates freely relies heavily on a single historical example: the divergence in economic fortunes of Silicon Valley in California and Route 128 in Massachusetts and the different cultural norms and noncompete enforcement policies attributed to each innovation cluster. The results are surprising. Contrary to the standard account, we show that there is little compelling ground to attribute Silicon Valley’s ascendance over Route 128 in the late 1980s and early 1990s to differences in the enforceability of noncompetes.35

There are multiple reasons. First, during Silicon Valley’s ascendance, California’s policy against noncompetes was clouded by several important exceptions. Second, California firms could significantly mimic noncompetes through trade secret and patent infringement litigation, long-term contracts, deferred compensation, and other mechanisms. Third, it is not clear that Massachusetts law substantially restrained employee turnover as an effective matter. Contemporary accounts of Route 128 in the heyday of the minicomputer industry in the 1970s and 1980s describe the same type of job hopping and spin-off formation associated with Silicon Valley. Fourth, Silicon Valley’s rise over Route 128 most likely stemmed far more from technological and economic fundamentals associated with the “PC revolution,” rather than fine distinctions in noncompete enforcement. Lastly, Route 128’s decline was relatively short lived, and it has remained a significant innovation center, especially in the life sciences and certain information technology markets.

Our original and comprehensive reexamination of the Silicon Valley / Route 128 narrative raises doubts concerning the widely accepted causal sequence running from prohibiting noncompetes to increased employee mobility to increased innovation. These doubts are intensified by a close analysis of recent empirical studies that are regularly cited as evidence that noncompetes impede innovation. Contrary to the characterization of these studies in much of the policy commentary by academics and governmental agencies,36 these studies suffer from significant methodological limitations, deliver statistically weak results, and do not provide compelling support for the view that banning noncompetes promotes innovation.

A fully informed policy position concerning noncompetes must reflect the uncertain state of our empirical understanding of the effects of these agreements in innovation markets. That is, it must reflect the fact that available evidence can neither support nor rebut any systematically adverse relationship between noncompetes and innovation outcomes in general. Only this measured conclusion, rather than the strongly “abolitionist” position that scholars and policymakers have increasingly advanced, is consistent with theoretical analysis that identifies the countervailing efficiency effects of noncompetes and other constraints on employee mobility. The free movement of talent implies efficiency gains from knowledge sharing and accelerated “n-mover” innovation. However, a blanket prohibition of noncompetes implies efficiency losses from uncompensated transfers of intellectual capital to competitors—which, far from being mere efficiency-neutral transfers, may discourage first-mover innovation and employee training, which may depress the development of human intellectual capital in the first instance.

Complex problems deserve complex solutions. Contrary to what is hastily becoming conventional wisdom, which is in turn being converted into concrete policy actions, there is no one-size-fits-all solution to this trade-off as a matter of economic analysis. Based on available evidence, there is no reason to believe that the efficiency gains from freely circulating human capital systematically outweigh the efficiency losses from uncompensated uses of intellectual capital. Rather, the net efficiency effect of noncompetes in any particular market depends on the interaction between multiple factors that vary across industries, firms, and types of employees. Even if California’s zero-enforcement policy has been locally optimal (or at least, sufficiently workable) from an efficiency perspective, it may be suited to a particular type of innovation economy at a particular time—an important but neglected qualification that Gilson made when he originally attributed Silicon Valley’s success to California’s refusal to enforce noncompetes.37 At the same time, we emphasize that neither theory nor empirics support an unqualified freedom-of-contract approach that enforces noncompetes in all circumstances absent evidence of fraud or coercion. Rather, we explicitly recognize the uncertainty involved in assessing the net efficiency effects of noncompetes. Using the error-cost approach developed in antitrust analysis and jurisprudence,38 we embed that uncertainty in our policy analysis, concluding that the common law’s reasonableness standard remains the best available instrument to reflect, albeit imperfectly, the trade-off between efficiency gains and losses inherent to limitations on employee mobility in innovation markets.

In sum, our Article makes three important contributions to the literature. First, it exhaustively reviews the widespread contention that noncompetes thwart innovation.39 Our detailed analysis shows that neither theory nor empirics supports the economic arguments commonly wielded in favor of prohibiting noncompetes.40 As a matter of theory, conventional wisdom emphasizes that noncompetes impede the circulation of intellectual capital while overlooking that noncompetes may encourage firms to cultivate employees’ human capital.41 As a matter of empirics, we contest the widely accepted view that Silicon Valley surpassed Boston because of supposed differences in noncompete enforcement, which tend to be exaggerated.42 A careful examination of the evidence shows that the Boston area has remained a significant innovation center and that technological and economic factors better explain Silicon Valley’s exceptional trajectory.43 Second, we uncover serious factual and other deficiencies in several widely cited empirical studies, which cast substantial doubt on those studies’ findings and policy implications.44 Third, based on our exhaustive review of the available evidence, we propose an original error-cost framework to analyze noncompetes, which provides a robust economic rationale for the common law’s reasonableness standard.45

The Article proceeds as follows. Part I describes the noncompete debate and, in particular, contrasts newly ascendant views favoring the free circulation of human capital with older views that recognize that reasonable contractual limitations on employee mobility may promote social welfare. Part II reexamines the standard narrative of the rise of Silicon Valley and the decline of Route 128, looking closely at multiple factors that may account for Silicon Valley’s exceptional success as an innovation center. Additionally, we review more recent empirical studies on the relationship between noncompetes, employee movement, and innovation. Part III revisits the range of policy options with respect to noncompetes, using an error-cost approach that has not been previously applied to the enforcement of noncompetes. We briefly conclude.

I. Old and New Views: From Agnosticism to Abolitionism

In this Part, we review two key stages in the intellectual history of the current debate over noncompetes and other restraints on employee mobility, and situate that debate within a larger body of economic thought relating to the economics of human capital. First, we review an earlier generation of law-and-economics scholarship, which identified the social costs and gains attributable to noncompetes and generally adopted an agnostic position concerning these restraints as a general matter. These scholars were therefore sympathetic to the common law’s reasonableness standard, which upholds or invalidates noncompetes on a case-specific basis. Second, we review a more recent school of thought that takes the strong view that the social costs associated with noncompetes typically or almost always outweigh the social gains, and therefore supports ending noncompete enforcement following California’s example.

A. Foundations: Becker and Marshall

Economically informed analysis of noncompetes and other restraints on labor mobility in innovation markets stands at the intersection of two foundational bodies of economic thought: Gary Becker’s breakthrough work on the economics of human capital and Alfred Marshall’s classic writings on the agglomeration economies that derive from the interchange of intellectual capital. Contemporary discussions of the legal treatment of noncompetes has relied (sometimes implicitly) almost entirely on the work of Marshall, which is a key reference point in the literature on innovation policy, while devoting little attention to the insights of Becker, widely recognized as the foundational work in the modern field of labor economics.46 We review both contributions briefly below and will then integrate these classic insights from innovation policy and labor policy scholarship throughout our analysis of noncompetes and other constraints on the mobility of human capital.

1. Becker: Human capital as an economic asset.

Nobel Prize–winning economist Gary Becker effectively founded the economic analysis of human capital with the publication of his landmark work, Human Capital, in 1962.47 Becker showed that economic analysis could be applied to the acquisition and cultivation of human capital, whether through education, training, or other mechanisms. From an economic point of view, human capital acquisition involves the use of scarce resources to maximize net expected value, as with any other costly activity. In implementing this analysis, Becker drew a key distinction between general and firm-specific human capital assets.48 General human capital refers to technical, managerial, and other skills and knowledge that have value across a broad pool of firms or industries.49 Firm-specific human capital refers to the narrower set of technical, managerial, and other skills and knowledge that have value (or have greater value) only at a particular firm.50 The scholarly literature that has followed Becker’s work has identified an intermediate form of human capital that is specific to an industry—namely, skills and knowledge that have value within an industry but not more generally.51 As discussed below, these different types of human capital give rise to different implications when analyzing the efficiency effects of noncompetes and other limitations on employee mobility.

2. Marshall: Industrial districts and agglomeration economies.

In the innovation context, economic analysis of noncompetes and other limitations on employee mobility often makes reference to the concept of “industrial districts,” originated by Alfred Marshall in his landmark treatise, Principles of Economics, first published in 1890.52 In a short passage in that work, Marshall proposed that certain industries benefit collectively from a free-flowing exchange of ideas, even if an individual firm may periodically suffer the loss of some portion of its investment in developing an innovation.53 In Marshall’s famous words: “The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air.”54 The movement of R&D personnel among firms is one of the key mechanisms by which the “mysteries of the trade” are disseminated and, according to Marshall, promote the general long-term welfare of all members of that innovation community. This line of reasoning is the basis for an extensive literature on the “agglomeration economies” that arise in innovation clusters in which geographically proximate firms and other entities draw from a free-flowing pool of human and intellectual capital assets to mutual advantage.55

B. The Old View: Restricting Labor Mobility Is Good and Bad for Innovation

The recent wave of academic interest in noncompetes is predated by scholars who had examined the efficiency of noncompete clauses and, explicitly or by implication, other restraints on employee mobility. Generally speaking, that view identifies both efficiency gains and losses that in general could arise from the use of noncompetes in innovation markets. Without an empirical methodology by which to quantify those potentially offsetting effects, that literature largely concluded that the net efficiency of noncompetes is indeterminate as a general matter.

1. The credible commitment problem.

Earlier scholars observed that human capital markets suffer from what economists call a credible commitment problem. Specifically, potential employees cannot provide adequate assurance to employers who are reluctant to invest in cultivating the human capital of employees who can simply move to another employer, thereby conferring an advantage on a competitor.56 When an employee leaves, the employer potentially suffers three costs: (i) it loses its training investment, which may involve a combination of firm-specific and general human capital; (ii) the employee may transmit proprietary information to a competitor; and (iii) the firm must incur costs to recruit and train a substitute employee, which again involves the transmission of firm-specific and general human capital.57

Without the ability to block employees from moving to a competitor, and without a sufficient up-front payment from employee to employer to cover the employer’s expected costs in the event of the employee’s departure, an employer faces two choices. Setting aside the possibility of various substitutes for deterring employee movement (most notably, deferred compensation arrangements and long-term employment contracts), the employer can (i) decline to hire the employee or (ii) hire the employee but underinvest in training (especially training that involves the cultivation of general human capital that has positive postemployment value) and the development and transmission of proprietary, often innovative, information.58 These concerns account for apprenticeship systems that predate modern intellectual property regimes: limiting the apprentice’s ability to switch employers enabled the master to internalize the gains from the intellectual capital transferred to the apprentice.59 Or, put differently, limiting the apprentice’s ability to switch employers enabled the apprentice to credibly commit against expropriating the employer’s investment in the apprentice’s human capital.

2. The noncompete solution.

Just like the apprentice contract, the noncompete clause can result in joint efficiency gains by enabling employment transactions (and associated knowledge transfers) that otherwise would not take place. This is beneficial not only for the employer but the employee and the industry as a whole. This point is overlooked in recent discussions of noncompetes that tend to emphasize how these clauses block employment opportunities and suppress innovation.60 However, it is important not to overlook the possibility that the absence of noncompetes can block certain other employment opportunities. Assuming the prospective employee is financially constrained and cannot post a sufficient “bond” against expropriating the employer’s training investment or R&D assets, an otherwise efficient employment transaction—and the associated cultivation of human capital—may not move forward. In that case, both employer and prospective employee are made worse off.

Even if the absence of noncompetes does not entirely block the employment relationship, it may distort the employer’s behavior during the term of employment and, as a result, sometimes disadvantage both the firm and the employee. At least three distortions are possible. First, the inability to enforce noncompetes may induce an employer to modify the internal allocation of team personnel so as to mitigate informational leakage from employee departures. For instance, Apple is famous for its secrecy practices and separate teams that work on different projects so as to minimize information transfer between them.61 Second, the firm may skew the allocation of training resources toward the cultivation of firm-specific human capital so as to maximize the employee’s value in the internal labor market but minimize the employee’s value in the external labor market.62 Third, the firm may underinvest in R&D by reallocating resources to activities in which it is not generating informational assets that an employee can transmit to another employer. In a world in which noncompetes are enforceable at some reasonable cost and high probability, these distortions are mitigated and the firm can allocate resources more efficiently among the available set of innovation and noninnovation activities.

3. A weak objection to noncompetes.

Some commentators argue that noncompetes may discourage employees from cultivating their human capital (or, specifically, general or industry-specific human capital)—which in turn may depress employees’ effort or creative output—due to the limited ability to access postemployment opportunities.63 This objection is not especially persuasive. Discouraging employees from acquiring human capital would appear to be inconsistent with rational profit maximization. Put affirmatively, any employer has an incentive to reward employees who enhance their firm-specific human capital (or some value-maximizing combination of firm-specific, industry-specific, and general human capital) and can therefore make a greater contribution to firm value. While there are inherent measurement and verification difficulties in assessing employees’ relative contributions in a team environment,64 firms clearly use a variety of compensation systems to at least approximately reward employee performance, including promotion, monetary bonuses, and more tailored compensation mechanisms.65 This is unsurprising: in a competitive market, any firm that includes noncompete clauses in its employment package has a rational self-interest in adopting incentive structures that correct for any underperformance effects that could arise as a result.66 Market forces reward firms who do so successfully and discipline those who do not.

4. A better objection to noncompetes.

It is certainly the case that enforcing noncompetes limits to some extent the mobility of R&D personnel, which may impede the agglomeration economies that arise from the regular dissemination of knowledge within an industry. To be clear, however, it is not precise to say (as is often said) that a noncompete “binds” an employee to a firm; rather, a noncompete requires that the employee or (more typically) a third party pay a fee demanded by the employer to obtain a waiver of the noncompete.67 Payments exchanged for waiver of a noncompete are mere wealth transfers without efficiency consequences from a short-term static perspective. Precisely understood, a noncompete is simply a mechanism by which resource-constrained employees can credibly commit to indirectly compensate their employer for training and knowledge leakage costs in the event employees depart for a competitor.68 The employee’s commitment is made credible by providing the employer with a contractual right that can be “sold” to the employee’s next employer.

This is not to say that there is no circumstance in which noncompetes can frustrate the efficiency gains associated with the circulation of human capital from one firm to another. First, even when an employer permits an employee otherwise under a noncompete to move to a new firm, the transaction costs of negotiating and executing a waiver of the noncompete generate static costs that would not be incurred if noncompetes were wholly unenforceable. Of course, like all contracting costs, such costs are tolerable when the social gains from contracting (here, for a noncompete) outweigh these costs.

Second, when the costs of negotiating and executing the waiver of a noncompete are sufficiently great so as to impede employee turnover, this may generate long-term dynamic efficiency losses to the extent that slowing down employee turnover impedes the transmission of intellectual capital that benefits the industry as a whole. These dynamic efficiency costs present a potential collective action problem because these costs may not be fully internalized by an individual firm in a given industry when that firm makes a decision whether to adopt and enforce a noncompete for a particular employee.

5. Evaluation.

The welfare effects of noncompete agreements can now be summarized. On the one hand, noncompetes support employers’ incentives to invest in employees’ human capital and R&D projects that would otherwise be subject to expropriation by departing employees. On the other hand, noncompetes raise the transaction costs involved in the circulation of human capital, which may impede the innovation process in the industry as a whole. Given these offsetting effects, earlier scholars generally concluded that economic analysis does not support a definitive position against or in favor of enforcing noncompetes in all circumstances.69 If noncompetes enable firms to secure gains from training and R&D investments, then barring noncompetes may reduce the common pool of technological knowledge that is available for circulation through employee movement. A ban on noncompetes would yield a net social gain over time only if the disincentive effects arising from uncompensated human capital transfers were exceeded by the agglomeration economies and other benefits associated with the unimpeded circulation of human capital. Without empirical evidence in any particular case, this analytical framework is agnostic in general with respect to the net long-term efficiency of those restraints. However, it does recognize a meaningful range of circumstances in which enforcing noncompetes could make firms and employees better off by resolving the credible commitment problem that might preclude or distort employment relationships.

C. The New View: Restricting Labor Mobility is Bad for Innovation

The traditional approach is intellectually modest in taking the view that enforcing noncompetes may have a net positive effect on innovation. By contrast, the new view on noncompetes tends to take the bolder view that enforcing noncompetes usually, if not always, discourages innovation by slowing down the flow of intellectual capital and impeding the agglomeration economies and similar benefits that fuel the innovation process. This new view consists of a two-part logical sequence. In step one, it claims that barring noncompetes accelerates employee movement. Stated precisely, this assertion reflects the assumption that noncompetes increase the transaction costs of human capital movements. In step two, the new view makes the stronger assertion that increased circulation of R&D personnel promotes innovation by facilitating knowledge spillovers that benefit the industry as a whole. The normative implication is simple and clear: the law should decline to enforce noncompetes in all circumstances.

1. Background: Saxenian and Gilson.

The new view relies on the work of AnnaLee Saxenian, a sociologist, and Ronald Gilson, a law professor, both of whom apply the Marshallian concept of agglomeration economies to interpret a key episode in the history of US technology markets. Both Saxenian and Gilson contrasted Silicon Valley with Boston’s Route 128 area to argue that institutional mechanisms—cultural norms and organizational forms in Saxenian’s analysis70 and a legal ban on noncompetes in Gilson’s analysis71 —that promote employee mobility can promote innovation by facilitating the flow of intellectual capital among competitors. Both authors identify these institutional differences as key factors in accounting for Silicon Valley’s rise over Route 128 as the country’s leading innovation center starting in the late 1980s.

More specifically, Gilson argued that California’s ban on noncompetes represented a solution to a collective-action problem. While no firm individually would agree not to adopt a noncompete and thereby expose its human and intellectual capital to competitors, it may be in all firms’ collective long-term interest to refrain from adopting noncompetes and thereby enjoy the resulting flow of knowledge spillovers.72 By implication, Massachusetts firms were caught in a collectively irrational equilibrium in which all firms imposed noncompetes and could not enjoy the collective gains that would result from a more fluid circulation of human capital. Gilson cautioned that this explanation may be specific to Silicon Valley and would not necessarily generalize to other contexts.73 Nonetheless, a significant body of commentary by legal scholars and economists has endorsed this proposition in stronger formulations and has made largely unqualified policy assertions that enforcing noncompetes and other restraints on employee mobility depresses innovation.74 For these scholars, California’s approach should be the rule, not the exception.

2. An initial critique.

The new view on noncompetes reflects a coherent and straightforward application of the standard collective-action problem in economic analysis. However, it is incomplete in significant respects. Specifically, the new view makes little effort to address the efficiency losses inherent to a legal regime in which a voluntary restraint on the mobility of talent is removed from the table of contracting options. Earlier analysis of noncompetes had recognized that an efficiency loss would arise in any circumstance in which an employee could not credibly commit against expropriating the employer’s human capital investment and R&D assets. The employer would respond by distorting the terms of employment to limit its training investments or the employees’ exposure to R&D assets or by declining to enter into an employment relationship at all.

A recent economic model formulated by Professor James Rauch shows that this loss can extend well beyond just one employment transaction.75 Consider a sequence of transactions consisting of (i) an initial employment transaction involving a parent firm and an individual employee, followed by (ii) a series of spin-off transactions involving employees who depart from the parent firm to form or join a spin-off firm, and then depart from the spin-off to form a new entity, and so forth. Noncompetes may raise the transaction costs relating to, and even frustrate, some portion, or even all, of the potential spin-off transactions. That is the focus of the “talent wants to be free” literature. However, it is important not to ignore the possibility that the inability to enforce a noncompete may preclude the initial hire by restoring the credible commitment problem, in which case the subsequent stream of spin-off transactions could be stunted or blocked entirely.76 Moreover, if noncompetes are not enforceable, even a certain portion of the set of spin-offs may face the same credible commitment dilemma and may be wholly precluded or move forward under distorted terms.77 If that is the case, then compared to a regime in which noncompetes are enforced, talent may be freer but it could well be worse off.

3. The empirical challenge.

As a theoretical matter, the new view on noncompetes, and the accompanying policy arguments in favor of a total or near-total ban, provide no reason to arbitrarily value the social costs attributable to noncompetes—primarily, potentially reduced circulation of intellectual capital (the focus of Marshall’s analysis)—more heavily than the social gains—primarily, potentially increased investment in employee training and R&D (the focus of Becker’s analysis). Given this uncertainty, we can only make progress toward assessing the relative intellectual strength of the new view based on empirical inquiry. Commentary by scholars and policymakers in favor of a ban on noncompetes often asserts that empirical data shows that noncompetes depress innovation.78 In the next Part, we look closely at that body of evidence, finding that nearly all of these studies are badly flawed and, even so, common characterizations of their findings often dramatically overstate the policy conclusions that the data can reasonably support.

II. The Evidence Against Noncompetes: A Close Look

In this Part, we undertake the most comprehensive examination to date of the two principal bodies of empirical evidence that are commonly referenced in support of the “talent wants to be free” school of thought. First, we review in detail the explanation provided by Saxenian and in particular, Gilson, to account for Silicon Valley’s dramatic rise over Route 128 as the world’s leading innovation center. We find significant reason to doubt that this fundamental shift in economic trajectories can be traced back to relatively fine differences in the enforceability of noncompetes between California and Massachusetts. Second, we review some of the most highly cited empirical studies that purport to show a three-step causal link between bans on noncompetes, increased employee turnover, and increased innovation. This exercise identifies important methodological and other limitations that cast serious doubt on the policy positions for which those studies have been cited.

A. Reasons to Doubt the Standard Account of the Rise of Silicon Valley

As of the mid-1970s, Silicon Valley and Route 128 were both viewed as key centers for innovation in the electronics industry, but with different strengths.79 Silicon Valley excelled in semiconductor chips while Route 128 excelled in minicomputers, a category situated between the supercomputer (or mainframe) segment dominated by IBM and the nascent “microcomputer” (in today’s terms, PC) segment pioneered by Apple.80 Starting in the early 1980s, Silicon Valley overtook Route 128 and secured its place as the world’s preeminent information technology center. Saxenian attributes the ascendance of Silicon Valley, and the decline of Route 128, to differences in industrial organization and cultural norms.81 The West Coast environment was characterized by a constant flow of technical personnel among a network of loosely connected firms, which spawned spin-offs that accelerated the innovation process. This structure was supported by industry norms that promoted information sharing and employee mobility.

By contrast, the East Coast environment was characterized by a small number of vertically integrated firms and exhibited little employee turnover. This structure was purportedly supported by industry norms that promoted loyalty to a single employer and discouraged information sharing. Building on Saxenian’s narrative, Gilson argued that the free flow of human capital could be attributed in part to California’s refusal to enforce noncompetes, while Massachusetts’s insistence on enforcing noncompetes may have stagnated the flow of human capital, resulting in a slowdown in innovation.82 Put together, Saxenian and Gilson’s work identifies certain informal and formal institutional characteristics that purportedly set Route 128 on a path to decline, while sending Silicon Valley on an upward trajectory.

Both Saxenian’s and Gilson’s accounts of the rise of Silicon Valley and decline of Route 128 have been widely adopted in the academic literature.83 In the discussion below, we identify several considerations that cast doubt on this now-standard account. These include: (i) there were several exceptions (and other legal causes of action) that substantially qualified California’s “ban” on noncompetes during this period; (ii) firms could substantially mimic the effect of a noncompete through compensation and other mechanisms; (iii) it is not clear that differences in Massachusetts law on noncompetes and trade secrets resulted in substantial differences in employee mobility as a practical matter; (iv) there are fundamental technological and economic factors that more plausibly account for Silicon Valley’s ascendance; and (v) Route 128 has continued to exhibit robust innovative performance.

1. Did California courts really never enforce noncompetes?

Scholars have not adequately questioned whether California courts in actuality declined to enforce noncompetes during the period in which Silicon Valley overtook Route 128. That seems to be the case based on the California statute, which declares void “every contract by which anyone is restrained from engaging in a lawful profession, trade, or business of any kind.”84 Given that blanket prohibition, however, it is curious that California firms often insert noncompete clauses in executive employment agreements. Two studies that focus on adoption rates of noncompetes in executive employment agreements at large publicly traded firms find these clauses in 58–62 percent of agreements with firms headquartered in California, as compared to rates of 70–84 percent at the same types of firms headquartered in other states (which generally enforce noncompetes subject to the reasonableness standard).85 Even more surprisingly, a broader study involving all types of employees finds that the incidence of noncompetes in California (19 percent) is approximately the same as observed in states that enforce noncompetes.86

This discrepancy between law and practice might be attributed to the possibility that technical personnel are unaware of California law and firms include a noncompete clause as an in terrorem device to be used against departing employees. That explanation assumes that these personnel do not consult legal advisors, particularly a potential new employer’s legal counsel, or review publicly available information about a basic point of law. Alternatively, one might argue that, because knowledgeable employees understand that noncompetes are generally not enforceable in California, it is not worth the transaction costs of negotiating with an employer to remove these clauses. At a minimum, it is worth inquiring whether the standard understanding of California law is entirely precise during the period in which Silicon Valley overtook Route 128.

In fact, it is not. Writing in 1989, a treatise on trade secrets law observed: “Despite the clear language of” California’s statute, “the California courts do not regard all covenants not to compete . . . invalid per se.”87 Specifically, there were at least five important circumstances in which California employers could have had some expectation of being able to enforce a noncompete during the period in which Silicon Valley overtook Route 128. While it remains the case that California courts did not generally enforce noncompetes against individuals during this period, it is incorrect to assume that a sufficiently motivated employer would never rationally invest resources in enforcing (and therefore could never credibly threaten to seek) enforcement of a noncompete against a departing employee.

- Narrow restraints. In 1987, the Ninth Circuit held that noncompetes were enforceable under California law if the noncompete narrowly restrained postemployment opportunities, as distinguished from a general restraint that barred entry into an entire profession.88 From the 1970s through the 2000s, litigants that pursued variants of the narrow restraint exception achieved mixed results, sometimes achieving success in (mostly) federal courts but usually not faring well in California state courts.89 In 1997 and 1999, the Ninth Circuit again applied the exception to uphold a noncompete covenant.90 Only in 2008, well after Silicon Valley had established its place as the world’s technology center, did the California Supreme Court resolve this uncertainty by rejecting the narrow restraint exception.91

- Sale of a business. Based on a statutory exception,92 both federal and state courts typically enforced (and continue to enforce) noncompetes executed in connection with the sale of a business. The exception applies to noncompetes entered into by majority target shareholders and possibly other target employees with smaller equity interests.93 This exception provides some of the legal logic behind the now-popular “acqui-hire” transactional structure, in which a large firm acquires a start-up firm primarily for purposes of retaining the services of its founders and senior managerial and technical personnel. Without a commitment from key personnel that they will remain with or at least not compete with the acquirer for some reasonable period of time, the transaction is not viable. This partially explains why exempting business acquisitions from noncompete enforcement limitations, which is the rule even in California, is likely to be, and is widely viewed as, efficient.

- Protection of trade secrets. Since a California Supreme Court decision in 1958,94

California law has recognized that the statutory bar against noncompetes does not extend to certain postemployment restrictions—most typically, nondisclosure and nonsolicitation covenants—that are enforced for the purpose of protecting an employer’s trade secrets or confidential information.95

Since the 1980s, California courts have periodically applied the trade secret exception to enforce nonsolicitation and nondisclosure obligations (and, in one recent case, even a noncompete clause “construed to bar only the use of confidential source code, software, or techniques”96

) that were found to be narrowly tailored to protect a trade secret.97

In 2008, the Supreme Court of California specifically declined to affirm or reject the trade secret exception.98 A recent federal court opinion summarizes the current state of California law on this point: “Although California courts have consistently ‘condemned’ agreements that place restraints on the pursuit of a business or profession . . . ‘an equally lengthy line of cases has consistently held former employees may not misappropriate the former employer’s trade secrets to unfairly compete with the former employer.’”99 Simply put: Section 16600 does not preclude an employer from preventing a departing employee via injunctive relief from joining a new employer by enforcing nondisclosure, nonsolicitation, or other similar postemployment obligations when doing so promotes the employer’s interest in protecting its trade secrets.

- ERISA. A California employer can avoid the statutory ban on noncompetes by embedding the noncompete in a deferred compensation or severance pay arrangement governed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974100 (ERISA). These clauses operate as a forfeiture mechanism that conditions entitlement to certain benefits under the plan upon compliance with the noncompete obligation. As observed in practitioner commentary, this exception typically arises in litigation concerning deferred benefit plans for highly compensated executives.101 In 1981 and 1987, the Ninth Circuit held that ERISA preempts state law, specifically including noncompete restrictions.102 California state courts have adopted the same position.103 This enforcement strategy is limited only by the ERISA requirement that a noncompete forfeiture clause cannot be applied to deprive the employee of benefits accrued after ten years of service.104

- Choice-of-forum clauses. California courts will not enforce a noncompete entered into under the law of another state that generally enforces noncompetes. However, prior to 2017, if an employer and former employee were subject to the jurisdiction of an out-of-state court that enforces noncompetes, and the decision was final in that state before any decision in a parallel California action, then a noncompete agreement was typically enforceable within California. In general, the two key factors at issue in such situations were whether (1) the agreement selected another state’s courts as the forum for disputes; and (2) whether the employee is now a California resident employed by a California employer. Although California courts will generally not enforce an out-of-state choice-of-law clause, especially if the defendant-employee is a California resident employed by a California firm,105 prior to 2017, they often respected an out-of-state choice-of-forum clause, even if the other state potentially applied its own law.106 In practice, this meant that California employees employed by a firm with corporate headquarters out of state—or out-of-state employees moving to California—could be subject to enforceable noncompete restrictions under a properly drafted agreement prior to 2017.107

2. Substitutes for noncompetes.

In addition to the five exceptions described above, California firms could elect (and still can elect) from a large menu of substitute legal and economic instruments to deter employee mobility. To illustrate these alternatives concretely, we can return to the case involving the former Google engineer who took a new position with Uber. As noted previously, the employee had been involved in developing Google’s autonomous driving technologies.108 Under California law, Google would appear to be powerless to prevent the employee from working for Uber. Even assuming that Google cannot wield a noncompete covenant, however, Google has several other credible legal threats at its disposal. Given the existence of these additional legal instruments, any marginal preclusive effect that can be reasonably attributed to noncompetes appears to be significantly attenuated, and would need to at least be accounted for in any empirical analysis comparing the differential effects of noncompetes on innovation between California and out-of-state firms.

- Patents. A firm may use patents to protect against knowledge leakage resulting from employee movement. Although a patent may not cover tacit knowledge per se, it may cover a product or method incorporating that tacit knowledge. Assuming the firm can bear the anticipated enforcement costs, the expropriation risk posed by a departing employee would then be limited to informational assets that fall outside the firm’s patent portfolio. A patenting strategy makes any departing employee less attractive to competitors, which implies that the employee will receive fewer or lower offers from other firms and is less likely to leave the current employer. Hence, even in a jurisdiction that is hostile to noncompetes, there may be significant patent-based obstacles that discourage employee movement. Consistent with these expectations, a 2009 empirical study found a deterrent effect on labor mobility in the US semiconductor industry proportional to a firm’s propensity to bring patent infringement suits.109 Another study finds that, while the likelihood of an acquisition increases when a target’s employees are subject to noncompetes, that effect weakens in the case of targets that hold strong patent portfolios, suggesting that patents substitute in part for noncompetes as a device for protecting against knowledge leakage after consummation of the acquisition.110

- Breach of contract. If the employee had signed a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) and then took a position with a competing enterprise, Google could potentially bring (or threaten to bring) a breach of contract claim against the employee. As noted earlier, there is no plausible legal challenge under § 16600 to the enforcement of an NDA so long as it is sufficiently tailored to promote the employer’s interest in protecting its trade secrets.111

The credibility of Google’s threat to sue to enforce an NDA would depend on the negotiated scope of the definition of “confidential information” in the NDA and the ease with which Google could demonstrate that the employee had actually breached the NDA’s confidentiality provisions at his or her new position. In certain jurisdictions, courts are willing to enforce NDAs that encompass information that would not otherwise qualify as a trade secret;112

in other jurisdictions (including California), Google may be required to show that enforcement of the NDA targets only nonpublic information that would be protected under trade secret law.113

Alternatively, Google could bring (or threaten to bring) a breach-of-contract claim if it had entered into a long-term employment contract or a shorter-term employment contract with periodic renewal at the employer’s option. (The former option may be unattractive to both employers and employees because it locks each party into a potentially unwanted long-term commitment that is difficult to mitigate even through the most carefully crafted provisions for early separation under certain circumstances.) In yet another variation, Google could bring a tortious interference with contract claim against Uber, on the ground that Uber was aware of the long-term contract to which the departing engineer was then bound.114

- Invention assignment agreements. In the technology industries, it is typical for employees to enter into invention assignment agreements, under which an employee agrees in advance that all “inventions” (as defined in the governing agreement) developed by the employee during the course of his or her employment are deemed to belong to the employer.115

Under such an agreement, Google could bring a claim against the departing employee if the employee is using an “invention” that the employee made while employed by Google. As long as Google’s claim could at least survive a motion to dismiss, it could credibly threaten to impose significant discovery and other litigation costs on the employee-defendant (or, more typically, the new employer who may have agreed to indemnify the employee-defendant). In a widely followed litigation over ownership of the “Bratz” line of dolls, involving Mattel (as plaintiff), Mattel’s former employee (as codefendant), and a smaller toy manufacturer (as codefendant), an invention assignment agreement provided the basis for several years of protracted litigation that burdened the defendant with substantial legal fees.116

Alternatively, Google and its former employee may have entered into an invention assignment agreement with a “trailer” clause, which would grant Google ownership over any inventions that the former employee developed within a certain amount of time following termination.117 That too may limit the employee’s attractiveness to any potential outside employer. The doctrine of assignor estoppel can have a similar effect in a departing employee scenario. Under that doctrine, some courts have held that not only is the employee precluded from arguing against the validity of a patent that the employee assigned to the former employer, but also any new employer of the employee is similarly precluded from doing so. The practical consequence: if the old employer brings a patent infringement suit against the new employer, the latter may be unable to argue in defense that the underlying patent is invalid. Like a trailer clause, this expansive understanding of the assignor estoppel doctrine may limit the attractiveness of an employee to any potential new employer.118

- Trade secret misappropriation. Google could (and did) bring a trade secret misappropriation claim against the employee and Uber as the new employer, alleging that the employee or Uber had used or disclosed trade secrets belonging to Google.119 In certain states (although not California today), even absent evidence of use or disclosure, Google could seek an injunction to prevent its former employee from joining Uber if the court found that the employee would inevitably disclose the employer’s trade secrets in his new position.120 Trade secret litigation in a departing employee scenario is not an uncommon occurrence in Silicon Valley. Intel, Broadcom, Cisco, Apple, and other Silicon Valley companies have been involved in prominent trade secret disputes involving former employees.121 Depending on the credibility of any such legal threat, and the potential injunction, damages, and litigation costs to which the employee and future employer could be exposed,122 Google may be able to dissuade Uber from hiring its employee. This effectively occurred in the Google-Uber litigation: first, Levandowski was barred by court order from working on certain projects at Uber; and, second, Uber fired Levandowski in connection with Google’s litigation and related allegations of trade-secret theft.123 Effectively, this approaches the result that would have been achieved if Google had been able to enforce a noncompete covenant against a departing employee. Aside from these clearly legal mechanisms, Google and Uber might enter into a mutual “no-hire” (also known as antipoaching) agreement. Beginning in 2005, Apple, Google, and other Silicon Valley–based companies reportedly entered into unwritten “no-hire” agreements to protect their trade secrets and to suppress wage competition among one another.124 Although these arrangements were ultimately dissolved following a settlement with the Department of Justice for alleged antitrust violations,125 they illustrate how firms that are precluded from using noncompetes may have strong incentives to use other mechanisms to dampen labor mobility.

- Economic alternatives to noncompetes. Even in the absence of any alternative legal instrument, employers have another potent mechanism by which to discourage employee movement: they can use deferred compensation mechanisms to encourage employees to remain with the firm.126 There are multiple methods. Employers can set the vesting schedules of deferred equity compensation (often a substantial portion of an employee’s compensation at high-tech firms) so that departing employees suffer an implicit financial penalty by departing prior to the date on which all their options to acquire stock in the company have been triggered. Cisco, a Silicon Valley incumbent and repeat acquirer of startups, typically requires that a target’s employees waive vesting rights (in the target’s stock) that accelerate upon an acquisition and adopt a new graduated vesting schedule (in Cisco’s stock), precisely in order to deter departures by the target’s key employees for a certain period of time following the acquisition.127 Alternatively, an acquisition agreement can skew the division of deal consideration such that a small portion is allocated to the up-front purchase price and the remainder is allocated to a future postacquisition date, contingent on the founders and certain other employees remaining with the acquiror postclosing for a certain period of time.128 In yet another variation, a recent empirical study shows that S&P 500 firms often pay severance to California-based executives in discretionary installments following separation (as contrasted with lump-sum amounts that the same firms usually pay to non-California-based executives immediately upon separation), subject to compliance with noncompete provisions in the executives’ employment agreements that are not directly enforceable through breach-of-contract suits.129

3. Was Massachusetts’s noncompete and trade secret law significantly different from California’s?

The traditional narrative relies on a significant difference in legal treatment between Massachusetts and California with respect to the enforcement of noncompetes and related doctrines that impact employee mobility. Below we look more carefully at comparative differences between Massachusetts and California law in the enforcement of noncompetes and trade secret law. We do not discern any meaningful differences with respect to trade secret claims. Although we do not contest that there were material differences in the enforceability of noncompetes between the two states during the historical period in question, the comparison is more nuanced than commonly explained, especially taking into account the above-noted exceptions to California’s oft-described “ban” on noncompetes.

- Trade secrets; inevitable disclosure. In general, there are few substantial differences in the trade secret doctrines followed by California and Massachusetts courts.130

Where there are fine differences, these do not necessarily support the conventional expectation that Massachusetts provides stronger trade secret protections. To illustrate these tendencies, we look more closely at the inevitable disclosure doctrine and its evolution in California and Massachusetts during the period in which Silicon Valley rose to preeminence. Under this doctrine, a court can enjoin an individual from working for a new employer on the ground that the individual will inevitably disclose trade secrets belonging to the former employer.131

This represents a plaintiff-favorable extension of trade secret law, which typically requires that the plaintiff show that the defendant has actually used or disclosed the trade secret after having misappropriated it.

As of the late 1970s and early 1980s, we are not aware of any indication in California or Massachusetts case or statutory law that either jurisdiction had explicitly recognized or rejected the inevitable disclosure doctrine or any equivalent under trade secret law. In 1984, however, it was California—not Massachusetts—that signaled openness to the inevitable disclosure doctrine by adopting the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA), which became effective the following year. California’s version of the UTSA, the California Uniform Trade Secrets Act (CUTSA), follows the language of the model statute and provides that a plaintiff can obtain injunctive relief under trade secret law if the court finds there is “threatened misappropriation.”132 Those two words mattered: in 1996, AMD, a leading California semiconductor manufacturer, successfully relied on the inevitable disclosure doctrine to secure a preliminary injunction preventing more than twelve of its former employees from taking certain positions at their new employer, Hyundai.133 Given the language in the CUTSA, and the outcome in the AMD-Hyundai litigation, it can be understood why a Silicon Valley practitioner observed in 1997 that it was unclear whether the inevitable disclosure remedy was available under California law.134

In 1998, the author of a leading treatise on trade secret law observed that California law authorized courts generally to intervene to protect against “threatened harm” and concluded:

“California has never rejected the fundamental idea that underlies the [inevitable disclosure] doctrine.”135 In 1999, a California intermediate appellate court even explicitly adopted the doctrine (although it ruled against the trade secret claimant and the court’s opinion was subsequently “depublished” by the California Supreme Court).136 Commentators observed that the court’s opinion reflected the actual law on the ground in some California lower courts: “The . . . decision now makes explicit what many trade secret practitioners have known for years: California courts will grant narrowly tailored injunctions in appropriate circumstances to prevent a former employee from performing certain tasks for a new employer to minimize the threat to a former employer’s trade secrets.”137

In the immediately ensuing years, the case law shifted in a more defendant-friendly direction, as several federal district courts applying California law138 —and, in 2002, a California intermediate appellate court—rejected the inevitable disclosure remedy,139 specifically distinguishing in the latter case between “inevitable disclosure” and the “threatened misappropriation” language in the CUTSA.140 Nonetheless, a contemporary observer wrote that it remained uncertain whether a California court might apply the inevitable disclosure doctrine, given that the 2002 case was a ruling by an intermediate appellate court.141 Reflecting this lingering uncertainty, a California court in 2008 recognized the continuing possibility of bringing a trade secret claim based on the “threatened misappropriation” language in the CUTSA.142 Although it is almost certain today that the inevitable disclosure doctrine is no longer viable in California in view of Edwards v Arthur Andersen LLP,143 during the ascendance of Silicon Valley in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, this was not the case.

During approximately the same period, the development of the law in Massachusetts concerning the inevitable disclosure doctrine followed a remarkably similar trajectory, with the only potential difference being that Massachusetts common law provided an even weaker basis for asserting the inevitable disclosure doctrine. Given that Massachusetts (unlike California) had not adopted the UTSA and therefore required that a trade secret claimant show actual use or disclosure by the defendant, there was arguably no basis under Massachusetts common law to issue injunctive relief under a theory of inevitable disclosure. In 1995, a federal district court (applying Massachusetts law) found that it was “inevitable” that a software developer would use his former employer’s information in his new position; however, the case involved a noncompete agreement and therefore it was not necessary for the court to address the inevitable disclosure doctrine.144 In 2002, a federal district court did address the doctrine directly and rejected it, stating: “Massachusetts law provides no basis for an injunction without a showing of actual disclosure.”145 As of 2003, a commentator summed up the state of the law by observing that “no Massachusetts appellate court has ruled on the viability of the inevitable disclosure doctrine, and the few Massachusetts trial court decisions dealing with the doctrine have been decidedly lukewarm about it.”146

Consistent with our general view stated at the outset of this discussion, with respect to the inevitable disclosure doctrine, it was actually California that was more protective of trade secret holders. Any current differences can be dated either to 2008, the year of the Edwards v Arthur Andersen LLP decision (insofar as it signaled California courts’ likely rejection of any effort by plaintiffs to seek injunctive relief under the inevitable disclosure doctrine), or 2018, when the Massachusetts legislature adopted its version of the UTSA. This gave rise to the same uncertainty that arose following California’s adoption of the UTSA in 1984. Following the model statute, the Massachusetts version refers to “threatened misappropriation,”147 which could provide a basis for Massachusetts courts to adopt the inevitable disclosure doctrine, although they may adopt California courts’ now-prevailing understanding that the “threatened misappropriation” language does not imply endorsement of the inevitable disclosure doctrine.148 While that particular point remains unresolved today, it is notable that practitioners have commented that acceptance by Massachusetts courts of the inevitable disclosure doctrine would run counter to those courts’ historical tendency to reject or at least resist application of the doctrine.149

- Noncompetes. During the time in which Silicon Valley overtook Route 128, and continuing through the present, it is certainly the case that Massachusetts law, as compared to California law, provided employers with a higher level of confidence in the enforceability of noncompetes. But the differences should not be exaggerated nor should it be assumed that Massachusetts employers have had unfettered ability to enforce noncompetes without constraint. Like almost all states, Massachusetts applies the common-law reasonableness standard. This standard limits the enforceable scope of a noncompete by duration, scope and geography, provided in all cases that the noncompete is deemed necessary to protect the employer’s legitimate business interests.150

For this purpose, Massachusetts courts have defined the employer’s legitimate interest narrowly. In a trilogy of cases decided in 1974, the Massachusetts Supreme Court emphasized that noncompetes were enforceable only to the extent required to protect the employer’s goodwill, trade secrets, or confidential information.151

Massachusetts courts apparently took these constraints seriously: writing in 1991, a leading practitioner of trade secret law observed that “Massachusetts courts have often refused to enforce non-competition agreements on the ground that no trade secrets or confidential business information were involved” and that “[i]n numerous cases, Massachusetts courts have cut back restrictions to make them reasonable.”152

Other obstacles stood in the way of a Massachusetts employer who sought to enforce a noncompete. Since 1968, Massachusetts courts have recognized the material change doctrine, which bars enforcement of noncompetes if the employee’s position and salary changed significantly since starting employment.153 In 1979 and 1982, the Massachusetts courts extended the reasonableness standard to employment contracts that required employees to forfeit certain deferred compensation upon termination, on the ground that these provisions implicitly operated as noncompetes.154 Additionally, Massachusetts courts have held that noncompete agreements are to be construed strictly in favor of the employee and, relatedly, have declined to enforce noncompetes if the contractual language has been deemed to be excessively ambiguous.155 Contrary to the standard narrative, Massachusetts courts during the decline of Route 128 were far from enthusiastic about noncompetes and applied the common-law reasonableness standard to limit their enforceability.

4. Did weak enforcement of noncompetes really cause the Valley to rise?

The standard narrative correctly observes that Massachusetts was an early pioneer of technological innovation. Ironically, the Boston area essentially originated what is now viewed as the Silicon Valley model consisting of a strong academic research complex coupled with a robust venture capital community and substantial movement of human capital among academia, startups, and large firms. In 1946, a Boston firm (the American Research and Development Corporation, or ARD) established the first major successful venture capital enterprise.156 Supported by federal defense funding and local VC investors, MIT and Harvard University labs spawned hundreds of spin-offs throughout the 1960s and 1970s.157 Those spin-offs included firms that later pioneered the “minicomputer”158 market such as Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) (founded in 1957 as a MIT startup with funding from ARD), Wang (founded by a Harvard physicist in the 1950s), Data General (founded in 1968 by ex-DEC engineers), and Prime (founded in 1972 by engineers from Honeywell).159

Contrary to Saxenian’s account of cultural norms, Paul Ceruzzi describes the most important Route 128 firm, DEC, as having been characterized by a nonhierarchical engineer-driven culture that dispensed with the formalities and bureaucracy of incumbents such as IBM.160 Certainly, as DEC and other large Route 128 firms grew, they tended to adopt vertically integrated structures.161 But it would be inaccurate to describe the Route 128 environment in its heyday as a monolithic industry consisting of a handful of vertically integrated incumbents. Although DEC and three other Route 128 firms (plus IBM) dominated the minicomputer segment in the late 1970s and early 1980s,162 observers and studies systematically documented that those firms spawned a continuing flow of small-firm spin-offs.163 An interview-based study of twenty-two Massachusetts-based computer firms between 1965 and 1975 found that half of the firms’ products “were the result of direct technology transfer from previous employers and another quarter indirect transfer.”164 A study of patent coauthoring patterns found similarly that Boston innovators were regularly involved in information exchange networks that were comparable in robustness (but not size) to those in Silicon Valley.165 In a manner akin to accounts of Silicon Valley, qualitative histories observe that Route 128 spin-offs could procure necessary inputs from a disaggregated network of small- to medium-size component producers and suppliers, assemblers, and distributors.166 A history of the period concludes: “[C]ompanies spinning off from other companies were at the very heart of the monumental growth that the Route 128 area experienced from the 1960s through the 1980s.”167

On the West Coast, Silicon Valley pioneered innovations in the semiconductor field and, by the late 1970s, was the recognized leader.168 Historical accounts of Silicon Valley’s semiconductor industry typically attribute its origins to the departure in 1957 of leading engineers from Shockley Transistors to form Fairchild Semiconductor, which generated a sequence of leading semiconductor firms.169 Semiconductor chips are a critical component in a wide array of computing and electronics products and operated as a launching pad for Silicon Valley to achieve dominance in information technology more generally.170 Even after lower-cost Japanese producers in the 1980s undermined the local memory chip production industry, Silicon Valley adapted by shifting resources to the design and development of customized chips171 and developing strengths in hardware and software markets. By contrast, the Massachusetts minicomputer industry did not recover as quickly from the entry of lower-cost workstations and personal computers.172 Massachusetts had bet on the wrong horse and was unable to recover the lead.