Stickiness and Incomplete Contracts

Both economic theory and legal theory assume that sophisticated parties routinely aim to write contracts that are optimal, in the sense of maximizing the parties’ joint surplus. But more recent studies analyzing corporate and government bond agreements have suggested that some contract provisions are highly path dependent, or “sticky,” with future agreements only rarely improving upon previous ones.

Analyzing half a million contracts using automated text analysis, this Article demonstrates that the stickiness hypothesis explains the striking lack of dispute resolution clauses that can be found in agreements between even the most sophisticated commercial parties. When drafting these contracts, external counsel rely heavily on templates, and whether a contract includes a dispute settlement provision is almost exclusively driven by the template that is used to supply the first draft. There is no evidence to suggest that counsel negotiate over the inclusion of dispute resolution clauses, nor that law firm templates are revised in response to changes in the costs and benefits of incomplete contracting.

Together, the findings reveal a distinct apathy toward addressing dispute resolution through contracting. From an institutional perspective, this suggests that the role of default rules in contract law is more important than is often assumed. Whereas traditional accounts hold that commercial actors would simply contract around inefficient defaults, the evidence produced in this Article highlights that defaults are significantly important for transactions between even the most sophisticated commercial actors.

Introduction

In the 1990s, Sprint PCS, one of the leading telecommunications companies in the United States, created a wireless affiliate program. Under the affiliate program, Sprint and its partners would conclude several agreements1 that established cooperation between the parties. Under the terms of these agreements, the affiliates would invest “hundreds of millions of dollars” in order to offer services on behalf of Sprint under the Sprint name.2 In return, a noncompete clause stipulated that the affiliates would be the exclusive providers of Sprint services in their regions covered by the affiliate program.3

On December 15, 2004, Sprint announced a planned merger with Nextel Communications, Inc., then the fifth-leading provider in the U.S. mobile phone industry. Nextel operated stores and offered services in many parts of the United States, including regions covered by Sprint’s affiliate program. After the merger, Nextel’s services would be rebranded under the Sprint name. The affiliates did not look favorably upon the planned merger. They alleged that the rebranding of the Nextel stores and services would cause the newly formed Sprint Nextel to directly compete against them in their service areas, thus violating the noncompete provision. Consequently, they filed for an injunction seeking to prevent the merger, alleging a breach of contract.

Conspicuously, however, while the agreements that Sprint concluded with its partners under the affiliate program included a choice-of-law clause determining the substantive law applicable in the dispute, none of them included a choice-of-forum provision that would determine where the partners could sue.4 To Sprint, this omission would become detrimental.

In 2005, the affiliates commenced parallel suits in both Delaware5 and Illinois.6 In 2008, in the context of a separate dispute regarding the acquisition of Clearwire Corporation by Sprint, they pursued a similar strategy.7

In an effort to minimize the harm resulting from this multiforum litigation, Sprint negotiated a forbearance agreement, in which the parties promised to limit their claims to the jurisdictions in which their respective lawsuits were currently pending and to coordinate discovery in the parallel suits in order to reduce costs.8 In addition, the parties amended their existing agreements to include a choice-of-forum provision.9 With its less adversarial affiliates, Sprint negotiated exclusive choice-of-forum provisions that would limit its exposure in the future.10 However, notwithstanding these attempts, the subsequent proceedings were so complex and costly that Sprint Nextel ultimately resolved the lawsuits by buying eight out of its ten affiliates. The largest of these transactions was the $4.3 billion acquisition of Alamosa Holdings in February 2006.11

The Sprint-Nextel merger provides a particularly striking example of the profound negative consequences that it can have to leave important terms in a contract unspecified. And yet, contractual gaps such as these are no exception in even the highest-value transactions between the most sophisticated actors. For instance, choice-of-forum provisions are similarly absent in the May 2011 underwriting agreement between Merrill Lynch (represented by Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP) and Celanese Corp. for $140 million,12 and the November 2015 common unit purchase agreement between Sunoco (represented by Latham & Watkins LLP) and Energy Transfer Equity for $64.5 million.13 Indeed, a systematic study of half a million “material” contracts reported to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) between 2000 and 2016 reveals that dispute settlement provisions are absent in more than half of all agreements.14

To students of contract law, this variation in the adoption of dispute settlement provisions presents an intriguing puzzle. We currently lack any theory that would predict parties to prefer the uncertainties associated with not having a dispute resolution clause over the predictability that comes with choosing a forum ex ante. And even if we could conceive of such a theory ex post facto, it would need to explain not only the existence of contractual gaps with respect to the forum, but also the great variation between different contracts. It is difficult to find consistency in the use of dispute settlement provisions across any coherent dimension that is often thought to induce homogeneity, such as the type of the underlying transaction or the industry. Indeed, even multiple contracts of the same company vary widely in their use of dispute resolution clauses, such that any given company sometimes includes them and sometimes does not.15

But if the explanation is neither the identity of the party nor the characteristics of the deal, what does explain the observed variation in contractual terms? To get an anecdotal taste of the empirical argument advanced in this Article, consider the case of Huron Consulting Group Inc., a leading provider of financial services. On July 31, 2007, Huron announced the acquisition of Callaway Partners, LLC. Callaway specializes in finance and accounting project management. The purchase price was $60 million, paid in cash.16 Then, on January 4, 2007, Huron announced the acquisition of Wellspring Partners LTD for $65 million.17 On the same day, Huron also announced it had entered into a definitive merger agreement to acquire Glass & Associates, Inc., a leading turnaround and restructuring firm, for $30 million.18 What is striking about these acquisitions is that, while the underlying contracts for all of them include a choice-of-law clause specifying the “internal laws of the State of Illinois” as the governing law,19 none of them include a dispute settlement provision.

In searching for consistency among the three transactions that may help explain this absence, a glance at the underlying agreements—as filed with the SEC—is instructive. What can be noticed is that all three contracts use the same font and format, and have similarly titled provisions.20 For instance, the substantive choice-of-law provision in all three contracts is titled “Applicable Law,”21 which is a rarity among these agreements. Indeed, the three agreements look like almost identical copies of one another. A study of the notice clause reveals who wrote these contracts. All acquired parties were represented by different sophisticated and successful law firms, namely Epstein, Becker & Green, P.C.; Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Nicholson Graham LLP (now K&L Gates LLP); and McDermott Will & Emery LLP. At the same time, what all three agreements have in common is the counsel representing Huron, an experienced partner of one of the largest law firms in the United States. Together, this suggests that all agreements were written based on the same template, provided by the acquirer’s counsel. This template, in turn, did not include a dispute settlement clause, and so neither did any of the agreements supporting the acquisitions.

At its core, this Article is a systematic and comprehensive investigation of what is exemplified by the case of Huron. It shows that the decision whether to include a dispute settlement provision is not typically made in an effort to maximize the joint surplus of the agreement. Instead, the presence of these clauses is almost exclusively driven by the lawyers that are hired to draft the contract between the parties. And even though most of the transactions under investigation have a value of several million—or even billion—dollars, the dynamics of the deal seem not to explain the lawyers’ decision to include or not include a dispute settlement clause. Instead, external counsel relies heavily on templates, and whether the final contract addresses the settlement of disputes is determined almost exclusively by the template that a law firm uses.

Exploiting the fact that some law firms collapsed during the period of observation, forcing lawyers to move to different firms and clients to seek new counsel, this Article further demonstrates that there is no evidence to suggest that companies strategically hire law firms that use the most beneficial template for their deals. Similarly, external variation in the default rules on forum choice seems to have no bearing on how parties approach issues of forum selection. Instead, the final contract is almost always identical to the first draft that was provided by one of the law firms. In contrast, the historical practice of the law firm receiving the first draft has no measurable bearing on whether the final contract specifies a forum. This suggests that external counsel virtually never bargains over or adapts dispute settlement clauses as found in the initial draft.

The results show that sticky drafting practices characterize the most fundamental aspects of commercial transactions across a wide range of contexts. In doing so, these results contribute to the literature on the economics of contract design and the role of the legal profession in several important ways.

First, much of modern legal and economic scholarship on contracts assumes that sophisticated parties routinely write optimal agreements. Meanwhile, the popular Coase Theorem teaches us that default rules do not matter if transaction costs are negligible, because parties would simply contract around inefficient default rules.22 Together, these assumptions have resulted in a lethargy with respect to academic, regulatory, and judicial interest in analyzing and optimizing the default rules that pertain to transactions between sophisticated commercial actors.23

The jurisprudence on the default rules of personal jurisdiction are a case in point. Over the past decade, the Supreme Court has made important innovations in the legal framework surrounding dispute settlement provisions for claims directed against corporations.24 However, this jurisprudence was developed almost exclusively in the context of tort law and consumer contracts.25 At the same time, and consistent with the view that sophisticated actors are able to optimize the rules themselves, the Court has done very little to promote clarity in the at times opaque default rules on forum choice in contract disputes at arm’s length. The results of this study lay bare an important practical limitation of theoretical approaches to these traditional accounts of contract design. Default rules such as those on forum choice can have important welfare implications because they affect not only the distribution, but also the final allocation of the contractual surplus. As such, it is worth spending scholarly, regulatory, and judicial attention to the design of efficient default rules even as they pertain to transactions between highly sophisticated actors.

Second, while the recent trend toward more empirical scholarship on contracts resulted in many valuable insights, one can observe a tendency for researchers to infer the efficiency of a clause from its prevalence in contracts between commercial actors. For instance, a desire to explain a seemingly incoherent set of contract terms has led to increasingly complex theoretical models explaining the interplay between formal and relational contracts.26 Only few have taken into consideration that the nuanced provisions in these contracts may not be optimized.27 The results of the study described in this Article suggest that it may be suitable to exert caution more frequently, thus determining efficiency on its own terms rather than to infer it from observed practice.

Third, this Article adds to and expands on the growing body of literature that emphasizes the significance of the law firm’s role in the allocation of contractual rights. Prior research has found that the law firm is an important actor in explaining the design of pari passu clauses in sovereign bond agreements,28 the prevalence of arbitration provisions in these contracts,29 exclusive forum provisions in corporate charters and bylaws,30 takeover defenses,31 and the language of S-1 statements filed in the course of initial or secondary public offerings.32 However, law firms do not seem to matter for the formulation of event risk covenants in corporate bonds when controlling for the underwriter.33 The study described in this Article is the first to investigate the influence of the law firm in a wide array of contractual relationships at arm’s length, overcoming the problem of a lack of generalizability that affects previous contributions. It is also the first Article to compare the law firm’s influence to that of the company by considering another important legal actor, the general counsel.

Finally, heterogeneity in contractual drafting practices suggests an important domain in which legal education can be value enhancing. In particular, by raising awareness of and advising their students on the pitfalls of template-driven contract drafting, law schools can enable students to significantly improve the distribution of contractual rights in favor of their clients.

This Article proceeds in seven parts. Part I offers a brief primer on the laws surrounding forum choice and dispute settlement clauses. Part II describes two theoretical approaches to the study of contract design and develops competing predictions on how contracts should be drafted. Part III introduces the data set and presents summary statistics. Part IV investigates whether the contracts in the data set reflect law firm or company preferences. Part V asks whether law firms ever bargain over the issue of forum choice. Part VI analyzes how resistant law firm templates are to changing circumstances in the legal environment. Finally, Part VII discusses limitations and the implications of the findings for the study and design of contracts.

I. A Brief Primer on Forum Choice

In order for a court to exercise authority in a case, it requires personal jurisdiction over the defendant. Personal jurisdiction is established either by law or by voluntary submission of the defendant. Through the use of forum selection clauses (or “choice-of-forum clauses”), parties can opt to submit to a particular court’s jurisdiction ex ante, i.e., before the dispute arises. Forum selection clauses can be narrow in scope, such that they pertain to a limited subset of contractual claims. In contrast, broad clauses affect all disputes arising out of the contractual relationship between the parties and may even encompass tort and statutory claims.34

Choice-of-forum provisions can be either permissive or exclusive. A permissive clause bars the defendant from challenging a court’s jurisdiction. However, the plaintiff may still pursue litigation in a forum other than the one specified in the clause. Permissive choice-of-forum clauses are thus strictly beneficial to the plaintiff. In contrast, exclusive choice-of-forum provisions not only bar the defendant from challenging a court’s personal jurisdiction, but also allow her to transfer any dispute to the court that is specified in the provision. As such, exclusive choice-of-forum clauses are both enabling and disabling to the plaintiff.

In addition to choosing the court that hears their case, parties also have the option to refer disputes to private arbitration.35 In principal, arbitration allows parties to customize procedural rules with great flexibility. In practice, however, many parties opt for commoditized, structured arbitral proceedings as they are offered by a few large arbitral organizations, such as the American Arbitration Association or JAMS.36 In doing so, the active choices of the parties are often reduced to picking the arbitrators and specifying the seat and venue of the arbitral proceedings. The seat determines the jurisdiction that parties can turn to if they seek judicial intervention, e.g., if they want an arbitral award to be set aside or annulled. The venue determines the physical location of the arbitral proceedings. Parties can also choose to submit some claims to courts, while leaving others to arbitration. For instance, in M&A contracts, disputes surrounding the adjustment of the purchase price due to a change in the value of the acquired company are often subjected to the evaluation of a private expert, such as an independent accounting firm.

To avoid confusion, it should be noted that this Article uses the term “dispute settlement clause” or “dispute resolution provision” to refer to the collective of both clauses referring parties to courts, as well as those referring them to arbitration.

If the parties leave the forum unspecified, the default rules determine whether a court has personal jurisdiction over the defendant. Under complete diversity, it is possible for both federal and state courts to exert jurisdiction over the defendant. Within each court system, the rules by which courts can exert personal jurisdiction in any given dispute are not conclusive and overall lack clarity, especially in the period under study here. Nonetheless, one can try to formulate a few broad principles that apply to company contracts of the type under investigation.

Principally, states have an interest in holding residents and nonresidents accountable if they perform certain acts that have repercussions within the state. This interest has to be balanced against the parties’ interest in not being subjected to litigation in a forum to which they have no relevant “contacts, ties, or relations.”37 This has effectively led to the implementation of a test by which states can exert jurisdiction over a defendant if the defendant has “minimum contacts” with the state.38 The contacts necessary to satisfy the “minimum contacts” requirement vary based on whether personal jurisdiction is asserted under principles of general or specific jurisdiction.

A court with general jurisdiction over a defendant can hear any case against that defendant, irrespective of the specific cause of action. Courts all over the country have long differed in the level of intensity of the relationship between a company and the state that is sufficient to establish general jurisdiction. The most expansive view is expressed in the “doing business” test. Under that test, it is sufficient for a company to do business “with a fair measure of permanence and continuity” in a state in order for the courts in that state to exert general jurisdiction.39 A recent line of Supreme Court decisions, which will be discussed in detail below,40 has decreased the expansive “doing business” test to the more narrow “essentially at home” test, which limits general jurisdiction over a company to its place of incorporation and its principal place of business.

Specific jurisdiction over a defendant is based on the particular action that gives rise to the claim. To define what constitutes “minimum contacts” with regard to specific jurisdiction, most states have enacted so-called long-arm statutes.41 Typically, these statutes provide that jurisdiction may be asserted by transacting business in a state, contracting to supply products or services within a state, or even by failing to perform contractually required acts in a state.42 Other characteristics that factor into the analysis in contract disputes, while not necessarily sufficient independently, are the place of contract negotiations,43 place of performance,44 place in which payments are to be made,45 and the choice-of-law provision.46

The Supreme Court has always upheld the validity of long-arm statutes,47 though its last decision dates back to 1985.48 As such, there are few universally applicable guidelines for parties to project the risk of being subjected to litigation in a particular forum, and the principles by which personal jurisdiction is established vary significantly.

This uncertainty is further amplified by a tendency of some courts to not cleanly distinguish between the requirements for general and specific jurisdiction in contracts cases. As Professor Charles Rhodes points out, general jurisdiction—if fully embraced by the courts—is “dispute-blind,” such that a breach of contract claim between a company registered in California and one registered in Pennsylvania could be litigated in Texas simply by virtue of the defendant having substantial business ties in the state, even though the contract has no other relations to Texas.49 In practice, however, some courts distinguish between general and specific jurisdiction simply based on the quantity of forum contacts. In these jurisdictions, pursuing a claim arising out of a breach of contract always requires some connection between the contract and the state, even under general jurisdiction. For these reasons, commentators have argued that, in some states, general jurisdiction is merely a “myth,” with courts essentially employing the same analysis as required under specific jurisdiction.50

What can then be taken away from this description of the default rule is that it induces uncertainty in contracting parties with respect to the particular court that will hear their case. In contracts between large public companies, the place of negotiations, place of performance, state of registration, principal place of business, and other provisions all might diverge, potentially subjecting the parties to litigation in multiple court forums, as exemplified by the Sprint-Nextel merger case in the Introduction.

II. Party Preferences and Stickiness

A study of over three million federal civil cases between 1979–1991 conducted by Professors Kevin Clermont and Theodore Eisenberg showed that, on average, there is almost one 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a) (change of venue) motion for each federal civil trial.51 The finding suggests that, even within the relatively homogenous federal court system, litigators assign great importance to the question which specific court hears their case. In addition, among all 557,014 relevant contracts cases, the probability for the plaintiff to win was 82% if the case was not transferred through a change of venue motion (and the venue thus reflects the preferences of the plaintiff). In contrast, if the case was decided pursuant to a successful § 1404(a) motion, the venue is more likely to reflect the defendant’s preferences, and the probability for the plaintiff to win drops to only 54%.52 Though it is necessary to exert some caution when interpreting this difference,53 it may suggest that the litigators’ interest in the choice of forum is well founded, as it can have a profound impact on the outcome of the suit.

In light of this evidence and uncertainty associated with the default rule, why is it the case that over half of all material contracts submitted to the SEC lack a dispute settlement provision?

Traditional contract theory assumes that sophisticated actors routinely write optimized agreements, and that the presence or absence of a clause is primarily driven by the costs and benefits conferred upon the parties,54 a view that is also held by the courts.55 Indeed, some commentators even argue that a belief in the ability of parties to maximize the contractual surplus is so deeply entrenched in the mindset of judges that it would be able to explain the vast majority of judicial reasoning and jurisprudence in contract law.56

At the same time, the literature on dispute resolution has not produced a theory that predicts parties will not include dispute settlement clause in their contracts. Instead, it is assumed that the cost-benefit calculus necessarily comes out in favor of inclusion, with the only remaining question being the type of clause that should be included. For instance, scholars have asked whether, and under what circumstances, parties prefer arbitration over courts,57 and how parties should design efficient procedural rules.58 In order to establish a baseline rate of dispute resolution clause usage under the null hypothesis that stickiness plays no role in contract drafting, it is worth revisiting the assumption of universal desirability by examining the potential costs and benefits of including such a clause.

A. Dispute Resolution Clauses: The Benefits

1. Decreased litigation costs.

Perhaps the most obvious benefit resulting from the inclusion of a dispute resolution provision is decreased litigation costs. As mentioned above,59 litigators perceive the forum as an important determinant for the outcome of the dispute and are willing to fight over it fiercely. Litigation over where to litigate can cost the parties significant time and—in the form of lawyer fees—considerable resources. In addition, these disputes can have substantial indirect costs, as exemplified by the case of the Sprint-Nextel merger, when multiforum litigation increased the uncertainty surrounding the legality of the merger, forcing Sprint to buy out most of its affiliates.

2. Efficient performance.

Including a dispute settlement provision can further incentivize the parties’ efficient performance with the contractual terms. In the Appendix,60 I formally develop this argument by introducing an extension to a standard model of forum choice by Professors Steven Shavell,61 Christopher Drahozal, and Keith Hylton.62 To develop a nonformal intuition for this result, consider that the parties’ incentive to breach a contract is related to the costs they face for the breach. These costs generally come in the form of dispute settlement expenses and damages awarded by the court. A party contemplating a breach of contract may be deterred if it predicts that its breach will subsequently be litigated in a jurisdiction in which litigation is cheap63 and damage awards are high.

Both expected dispute settlement expenses and damages vary from one jurisdiction to the other. This is certainly true for the difference in expenses between litigation and arbitration, provided that parties only bear the full costs of their disputes in arbitration. Indeed, studies indicate that about 20% of the total costs of complex arbitral proceedings are paid to the arbitration institution and the arbitrators.64 In the domestic court system, this amount is largely subsidized by the public. But even within forums of a particular type, costs can vary substantially. For example, most corporate legal firms have a significant presence in and familiarity with the courts of New York, lowering the costs for disputes litigated in the state, compared to litigation in a state that corporate lawyers are much less familiar with. Further, different states have different procedural laws, which, in turn, alter their costs. For example, it is well known that civil jury trials on average take twice as long as bench trials,65 but that not all states enforce jury waiver clauses, which potentially exposes parties to longer and more costly litigation.66 In addition to dispute settlement costs, damage awards can also vary with the dispute settlement mechanism and forum. Again, the most significant difference exists between courts and arbitration, where some evidence suggests that arbitrators might be susceptible to granting awards that split the baby to maximize their chances of reappointment.67 But even within the domestic judiciary, awarded damages can vary, for example, because of differences in the pool of juries or judges.68

Parties that choose their dispute settlement mechanism have the possibility to optimize the incentives provided in order to guarantee that a contract is only breached if it is efficient to do so. Parties that do not agree on a dispute settlement provision forego this possibility, allowing plaintiffs to unilaterally choose forums that are particularly favorable to their claim. Whether the expected dispute settlement expenses and damages awarded in the jurisdiction chosen by the plaintiff unilaterally exceed those awarded by the court or arbitrator that is chosen ex ante by mutual agreement cannot be determined generally. On one hand, it is evident that the plaintiff will have an interest to choose a forum that is particularly favorable to her claims. On the other hand, not choosing the forum ex ante significantly diminishes the set of jurisdictions in which the plaintiff can sue absent consent by the defendant, such that the plaintiff’s options are severely limited. However, what should be noted is that only in exceptional circumstances will the plaintiff’s choice of jurisdiction provide efficient incentives to the defendant. In all other cases, the defendant may be over- or underdeterred, leading to an expected welfare loss for the contractual parties.

3. Aligning forum and substantive law.

Lastly, benefits are conferred on parties who align the substantive law governing the contract with the courts that will hear their disputes. As Thomas McClendon notes, courts have a competitive advantage in deciding their own state law, one that stems from their familiarity with the applicable rules.69 That divergences between the choice-of-law and choice-of-forum are undesirable is further supported both by the data presented here, as well as by interviews conducted with transactional attorneys. As Table 4 demonstrates, contracts that specify both a governing law and a court forum hardly ever create a dispute resolution process in which courts apply a law from another state. In addition, interviews have shown that aligning the substantive law and forum are among the primary considerations governing the drafters’ choice between different forums.70 However, if parties do not specify a forum, the chance for the substantive law to differ from the forum increases significantly, making the outcome less predictable and potentially longer due to the unfamiliarity of the judges. Again, the Sprint-Nextel merger provides an illustrative case, where a Delaware court applied the substantive law of Pennsylvania, further amplifying the complexities of the dispute.71

B. Dispute Resolution Clauses: The Costs

1. Negotiation and drafting costs.

Perhaps the most evident costs associated with the inclusion of dispute settlement provisions are the costs of negotiations and drafting. Because the forum can have a significant impact on the outcome of a potential dispute, it is possible that any attempt for one party to include its preferred forum would be met by fierce opposition. It might then be best for the parties to leave the forum unspecified in hopes that a dispute does not occur between them. And even if parties can agree on a preferred forum, provisions still have to be drafted. Drafting could cost the parties significant resources, even though those can be mitigated through the inclusion of boilerplate language.

However, while comprehensive data on negotiation and drafting costs do not exist, available evidence suggests that these costs are negligible. In particular, a 2014 survey of general counsel in the Public Utility, Communications, and Transportation (PUCAT) industries conducted by the American Bar Association suggests that parties typically spend less than one hour negotiating and drafting dispute settlement provisions in “significant commercial contracts,” implying that their direct costs do not exceed $5,000.72 This is consistent with other survey evidence in which drafters describe dispute settlement provisions as “2am clause[s]” that are included without much negotiation after the substantive terms of the contract have been determined.73

2. Negative signaling.

Another potential cost associated with the inclusion of dispute resolution clauses is negative signaling. Because a contractual gap raises the ex post costs of dispute settlement, those who bring up the issue of dispute settlement during contract negotiations could convey to the other side that there is a significant probability for a dispute to arise. Conversely, not specifying the settlement mechanism ex ante may indicate trustworthiness and provide assurances that any dispute can be solved amicably between the parties.74

This argument, however, is only somewhat plausible in the context of dispute resolution clauses. As mentioned above, these provisions do not have to be exclusive, but can also be nonexclusive. Nonexclusive choice-of-forum provisions are strictly beneficial to the potential plaintiff, as they extend the set of jurisdictions she can sue in. Hence, rather than leaving the forum unspecified, a contractual partner seeking to indicate trustworthiness has an incentive to include nonexclusive choice-of-forum provisions that confer personal jurisdiction on courts that are particularly unfavorable to her claims. In addition, one of the central functions of contracts is to allocate risks and contingencies between the parties. It is thus true that virtually any provision in a contract conveys some form of private information. However, we see much less heterogeneity in some of these other terms. For instance, most contracts include a choice-of-law clause, even though specifying the substantive law governing the contract may have stronger implications for the parties’ future behavior than forum choice. Lastly, in interviews I conducted in the context of this study, both senior drafters and general counsel have described signaling costs as an “academic” concern that bears no relevance in practice.

3. Relational contracting.

It has been argued that some dimensions of contractual relationships should remain informal because formalizing them damages the relationship between the parties.75 For instance, based on interviews with sixty-eight individuals from business and law, Professor Stewart Macaulay notes that “[d]isputes are frequently settled without reference to the contract. . . . There is a hesitancy to speak of legal rights or to threaten to sue in these negotiations.”76 If true, it may be the case that those who indicate reliance on dispute settlement mechanisms risk formalizing their relationship and foregoing the advantages that come with trust. However, again, it is not immediately obvious why a similar argument should not apply to other clauses, such as choice-of-law provisions, as well.

4. Uncertainty as a screening device.

Lastly, commentators have argued that, under specific circumstances, parties may prefer uncertainty in a contract over the certainty of definitive terms and contractual language.77 The intuition behind this result is that uncertain terms that spur costly litigation present a form of ex post screening that separates claimants with strong claims from those with weak claims, potentially increasing the overall surplus of the contract. In addition, costly litigation may incentivize beneficial renegotiation of the contract. Note that, similar to the benefits conferred through efficient performance, this argument does not presuppose that parties actually litigate. Bargaining in the shadow of costly litigation may be able to increase the contractual surplus without the parties ever going to court.78

One may be inclined to argue that this rationale provides another reason for why parties omit a dispute settlement provision. After all, it was pointed out above that the uncertainty associated with leaving the forum unspecified can spur litigation over where to litigate. If high litigation costs are indeed desirable, then omitting a dispute resolution clause may further parties’ interests by increasing litigation costs. However, the flexibility granted to parties in designing their dispute settlement provisions makes this argument only partially compelling. Assume, for instance, that the default rules allow parties to litigate in New York and that litigating in New York is cheap because both parties are incorporated and conduct their business in the state. If the goal is to increase litigation costs in order to deter weak claims and promote renegotiation, the parties could simply opt for the exclusive jurisdiction of another, less competent, more costly, and geographically more distant jurisdiction. Indeed, only if we assume that the expected costs of omitting the dispute resolution clause exceed those of litigating in the most expensive jurisdiction, it is conceivable that parties’ optimal strategy is to not include any clause at all.

Overall, including a dispute settlement provision may create a number of different costs and benefits. While in most instances, it is reasonable to assume that parties would want to specify the forum ex ante, it is at least plausible that under some particular circumstances, a cost-benefit calculation suggests that the costs of inclusion outweigh the benefits. Hence, even under the baseline assumption that dispute settlement provisions reflect party preferences, we may observe some heterogeneity in their adoption.

C. Law Firms and Contractual Stickiness

Traditional theory, and with it the preceding discussion, views contractual parties as unitary actors and the costs and benefits to these unitary actors as determinative for contractual design. But more recently, this view has been challenged by a group of legal scholars. Through a series of empirical studies focusing primarily on covenants in corporate and sovereign bonds, they show that many high-value contracts are not merely a reflection of the costs and benefits conferred upon the parties.79 Instead, they argue that the contractual drafting process is “sticky.”

At its most fundamental level, stickiness simply describes path dependence. That is, whether a certain provision is included in the contract depends on whether said provision has been included in previous agreements. Note that some level of path dependence is perfectly consistent with traditional theory. After all, negotiating each term in an agreement can impose high transaction costs, so parties might benefit from using standardized (or “boilerplate”) agreements.80 However, where the stickiness literature goes beyond traditional theory is in its consideration of the relevant actor inducing the standardization.

In particular, the relevant literature relaxes the assumption of contractual parties as unitary actors. It argues that that the provisions in the agreements are based on templates used by the drafting law firms.81 These law firms would generally be resistant to making changes to their templates, even if it were for the good of their client.82 The unwillingness to amend their templates would then lead to a particularly profound path dependence that could lock parties into suboptimal agreements for extended periods of time.83

Several rationales have been proposed that may help explain this resistance. Some argue that increased economic pressure to commoditize legal services leads to standardization, and that it is economically infeasible to deviate from these templates.84 Others suggest that lawyers may be risk averse and afraid of the unknown scenarios that may unfold if the templates are tampered with, ultimately leading to a status quo bias.85 Yet others suggest that lawyers simply make routine cognitive errors and do not notice—or overlook—mistakes in their drafts.86 Sometimes, contract terms may also be “skeuomorphs” that lose their meaning over time,87 while continuously being used without much reflection—a phenomenon referred to as the “black hole problem.”88

What all of these explanations have in common is the conclusion that lawyers draft agreements that do not achieve an optimal allocation of the contractual surplus.

A few empirical studies have provided convincing evidence to support this hypothesis.89 However, currently, certain limitations prevent the stickiness literature from growing into an essential part of contract theory. First, the findings from previous studies are not necessarily generalizable. The majority of past inquiries focus on corporate charters and bylaws,90 as well as publicly issued corporate91 and sovereign bonds.92 However, none of these documents is the result of a traditional bargaining process at arm’s length that characterizes most commercial relationships. Charters and bylaws, though arguably susceptible to market incentives, are drafted by the corporation unilaterally.93 Similarly, though both bond issuers and holders can be large and sophisticated financial actors, the bond indentures for publicly issued bonds are rarely the result of a traditional bargaining process. Instead, bond issuers and underwriters cement the indentures, while bondholders do not participate directly.94 While underwriters have an incentive to create marketable bonds, they are also interested in preserving their relationship with the issuer, who wants to minimize constraints on the companies’ or governments’ future conduct. As such, bond indentures typically start with terms strongly favoring the issuer, and amendments are made in favor of bondholders only to the degree necessary to ensure marketability.95

Another aspect that makes bond indentures, specifically for corporate bonds, especially sticky—and conclusions drawn from their analysis difficult to generalize—is the existence of several model indentures that are widely used across the industry. The American Bar Association has published the ABF Model Debenture Indenture (1965), the ABA Model Simplified Indenture (1983, revised in 2000) and the Model Negotiated Covenants and Related Definitions (2006). It is believed that the model indentures provide a widely used template across the industry,96 again increasing the probability for sticky covenants to evolve. In contrast, the vast majority of contracts does not evolve out of an industry-wide model agreement, making results of the contracts under study here more representative and generalizable.

It should also be mentioned that studying bond indentures means studying one of “the most involved financial document[s] that has been devised.”97 The covenants that are the subject of previous studies typically deal with complex issues that require not only knowledge of the relevant legal rules, but also a significant level of expertise in the relevant financial market dynamics and incentive effects.98 The impenetrability of the underlying legal issues makes it especially likely for suboptimal rules favoring the issuer to emerge, given that most investors neither fully process, nor have an incentive to invest in identifying, how each covenant might affect their return or the default risk.

The lack of a traditional bargaining process, the existence of widely used templates, and the high degree of complexity raise questions as to whether the stickiness of contract provisions is an odd feature characterizing a small subset of particularly complex and standardized agreements, or whether law firm templates are an important determinant in explaining the resource allocation resulting from commercial contracts more generally.

This Article addresses many of these limitations by examining whether the stickiness hypothesis is able to explain the rarity of and variance in the use of dispute settlement provisions. By analyzing a broad range of corporate agreements across multiple issue areas, it provides a picture of how contracts are written outside of the area of bond issuances, allowing it to test whether rigidity is a characteristic of contract provisions more generally, or whether it is specific to certain issue areas. In addition, dispute resolution clauses lie at the core of legal expertise and touch upon an issue that is comparatively simple to comprehend and taught in every first-year law school curriculum. Hence, finding path dependence in the prevalence of dispute resolution clauses makes for an especially compelling case of stickiness in contract drafting.

Another advantage of the study described in this Article is that the analysis of contractual gaps significantly reduces the number of potential explanations for observing stickiness. Previous studies focused on the wording of a covenant and how it relates to the presumed goal of the indenture, concluding that commercial actors are incapable of optimizing the wording of a clause. But choosing the optimum wording of contractual language is a choice from a space with virtually infinite alternatives. Trying to find the optimum choice among a great number of alternatives in such a setting quickly becomes economically infeasible, incentivizing actors to settle for contract terms that are good enough to achieve their goal without the need to optimize the text—a decision-making process also known as “satisficing.”99 In contrast, this study focuses not on the optimal wording of the clause, but on its inclusion. The concept of satisficing is an unsuitable explanation for the existence of gaps, as parties should have clearly defined preferences on the inclusion or noninclusion of a clause.

Theoretical notions invoked by scholars in the 1990s to explain a suboptimal allocation of the contractual surplus are similarly unsuitable explanations for the existence of contractual gaps. For instance, it has previously been proposed that sticky drafting practices can be explained through the economics of networks and learning.100 By this account, because the benefits of standard clauses are often conferred only after they have been widely adopted in the future, companies are faced with a collective action problem that would cause them to choose a standard that is suboptimal from a social welfare perspective.101 Further, once a firm has accrued expertise and network benefits, switching would become prohibitively costly.102 Both of these rationales seem unlikely explanations for observing stickiness with respect to the omission of dispute settlement provisions. That is because parties who do not include such a clause can neither gradually improve upon it, nor can they feasibly be described as any coherent network. Given that leaving the forum unspecified introduces uncertainty, a line of reasoning which postulates that a fear of the unknown and an extreme level of risk aversion may explain some of the drafters’ behavior seems similarly ill-suited as an explanation.103 Thus, if it can be shown that stickiness characterizes the choice not to include a dispute resolution clause, this can be seen as compelling evidence in favor of one of the less discussed mechanisms, such as agency costs, cognitive errors, or another, yet undeveloped, theory.

D. Hypotheses

In this Article, I test the stickiness hypothesis in three steps. First, I examine whether the law firm is a relevant actor in the decision whether to include a dispute settlement provision. I investigate this question by considering the degree to which these clauses vary with external counsel, holding the parties to the agreement (and other observable characteristics) constant. To promote causal interpretability, I also exploit law firm closures as an external shock that forces both companies and drafters to change their law firm.

After establishing that the hiring decision of external counsel significantly influences not only whether or not parties have a dispute settlement provision in their agreement, but also which jurisdiction or arbitration organization they opt for, I examine the influence of the law firms’ use of templates. In particular, I identify the law firm that proposed the first draft to an agreement, as well as the template the draft is based on. With this information in hand, I consider whether law firms bargain over the presence or absence of forum choice as found in the template.

Lastly, I consider whether law firms can be induced to make changes to their drafting practice in response to external shocks that change the costs and benefits of including the dispute resolution clause. To that end, I exploit the fact that a series of Supreme Court decisions significantly altered the default rules on forum choice and investigate whether these decisions changed the ways in which parties implemented forum selection clauses into their agreements.

III. Data

This Article uses the collection of all “material contracts” filed with the SEC through its Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system (EDGAR) between 2000 and 2016.104 The SEC requires registered companies to report every “material contract,” which encompasses “every contract not made in the ordinary course of business that is material to the registrant.”105 During the period of observation, a company had to register with the SEC if it had made a public offering or had “total assets exceeding $10,000,000 and a class of equity security . . . held . . . by five hundred or more . . . persons.”106

Companies attach the agreements to their annual reports (Form 10-K), quarterly reports (Form 10-Q), and to reports filed due to important events and changes between quarterly reports (Form 8-K). Similar provisions exist for foreign companies, which have the option to report using Forms 20-F and 6-K. In addition, during mergers, the relevant contracts are reported as exhibits to Form S-4. I automatically collect all of these reported agreements for all registered companies through EDGAR. Overall, the data set includes 780,689 agreements between 2000 and 2016. From those, I drop 272,837 duplicates and amendments to existing contracts for a total of 507,852 unique contracts submitted by a total of 18,641 companies.

EDGAR includes data on the party that filed a contract and its industry. I assume the filing party to be the first party to the contract and its industry to be the industry pertaining to the contract. I then write a search algorithm that uses regular expressions to identify the paragraph in the contract that includes the parties to the dispute. The algorithm is described in detail in my other work.107 I scan this paragraph for the mention of any of the 630,106 companies and individuals that have ever disclosed information through filings with the SEC in order to supplement the information on the parties to the contract.

Next, it is necessary to identify whether a given agreement includes a dispute resolution clause and, if so, what type of dispute settlement provision the parties agreed on. Due to the large number of contracts, I train a machine learning algorithm that automatically identifies dispute resolution clauses. Separately, for clauses referring parties to courts and arbitration, training proceeds in these six steps:

- I split each contract into paragraphs and draw a random sample of 48,949 paragraphs.

- I manually inspect the sample, coding each paragraph as “1” if it contains a dispute settlement provision and “0” otherwise.

- I randomly divide the paragraphs into two sets, a “training set” (80% of the data) and a “test set” (20% of the data).

- With the training set, I calibrate an algorithm (“classifier”)108 to identify terms and phrases that are most indicative of dispute resolution clauses, based on the preprocessed text in the paragraph.109

- Using this trained classifier, I predict whether the provisions in the test set (which the classifier has not seen previously) are dispute resolution clauses or not.

- I compare the predictions generated from the trained algorithm to my hand coding in order to evaluate the performance of the classifier.

This approach correctly classifies 99.88% of the paragraphs. Overall, it can be considered as very accurate, with no strong tendency for false positives or negatives.110

I use a similar process to identify whether a contract includes a clause specifying the substantive law governing the contract and, if so, which law governs. In a last step, I use a combination of search terms and regular expressions to identify the type of the document (e.g., loan agreement, licensing contract) and the form of the document (e.g., agreement, plan, policy). The entire procedure is described in greater detail in my other work.111

In order to obtain data on a company’s general counsel, I rely on FactSet. Though it is one of the most comprehensive data sets on general counsel, it has two important limitations. First, the data set contains information only on individuals who are currently active as general counsel. Hence, I do have information about a company’s current general counsel and how long she worked for said firm, but I have no information on who the general counsel was prior to the current counsel.112 Second, the general counsel information on FactSet is limited to companies publicly traded on large U.S. stock exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ. In total, the data set includes information on 4,201 general counsels for 4,670 companies drafting a total of 138,617 agreements. Because the SEC uses a company central index key (CIK) to identify companies, whereas FactSet uses the security identifiers CUSIP and ISIN, I rely on Compustat to translate CIKs to ISINs and merge the two data sets.

|

|

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

Med |

IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

2008 |

4.35 |

2000 |

2016 |

2008 |

7 |

|

Dispute Resolution Clause |

0.44 |

0.50 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Forum |

0.30 |

0.46 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

FSC Length |

220 |

154 |

29 |

809 |

181 |

196 |

|

Arbitration Clause |

0.19 |

0.39 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Arb. Clause Length |

324 |

245 |

27 |

1,128 |

255 |

313 |

|

Choice of Law Clause |

0.75 |

0.43 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

CoL Length |

79 |

77 |

16 |

401 |

47 |

66 |

|

U.S.–U.S. |

0.89 |

0.31 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

U.S.– |

0.10 |

0.30 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

Foreign–Foreign |

0.01 |

0.09 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

Table 1 contains summary statistics describing the contracts in the data set.113

Eighty-nine percent of contracts, the vast majority, are concluded exclusively between U.S. parties. Only 44% of agreements in the period of observation include dispute resolution clauses, even though 75% include a clause specifying the substantive law of the contract. This may seem puzzling, given that both types of clauses seek to address issues arising out of uncertainties regarding the relevant and applicable legal framework. Among dispute resolution clauses, those that refer parties to courts are more prevalent than arbitration clauses (30%

versus 19%).

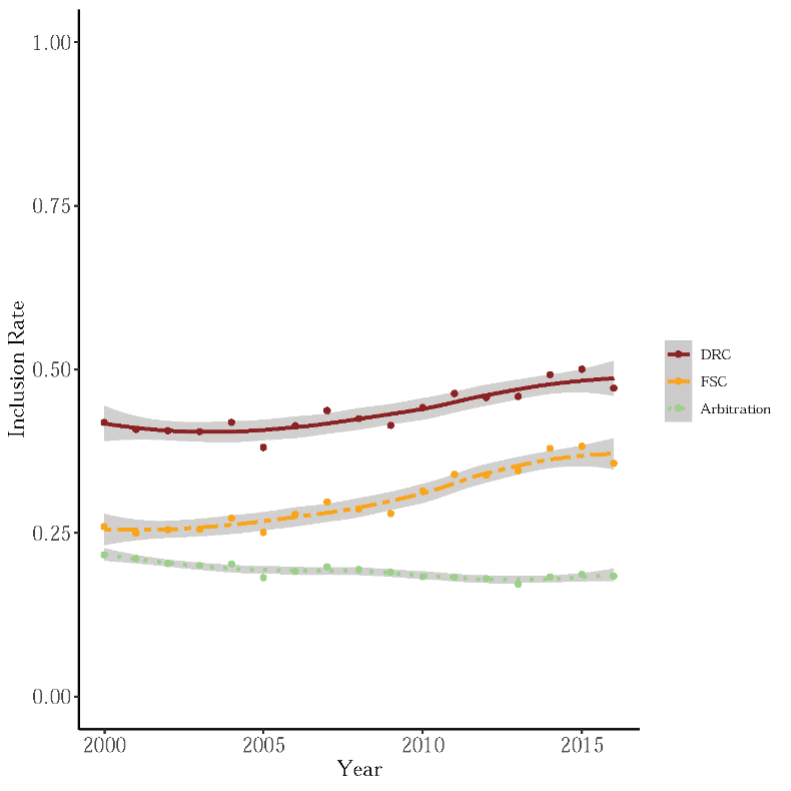

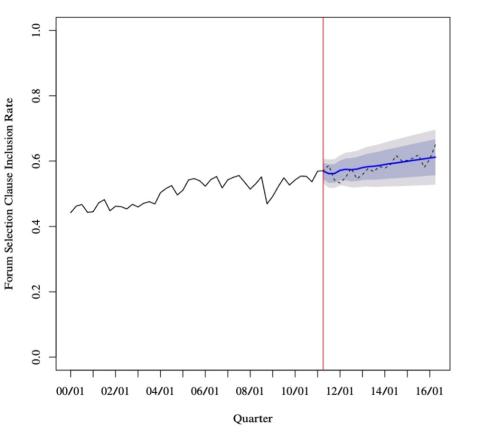

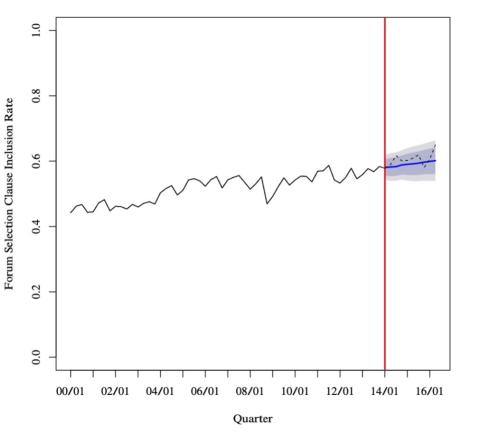

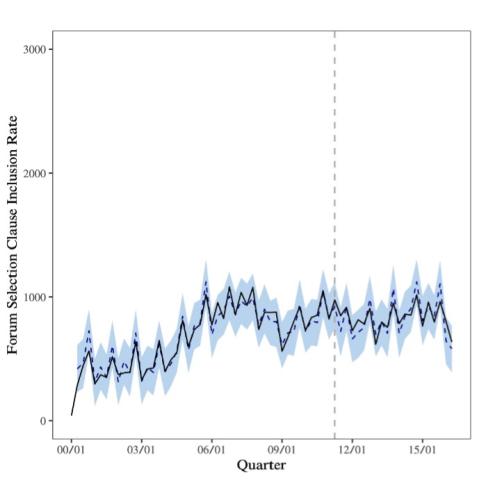

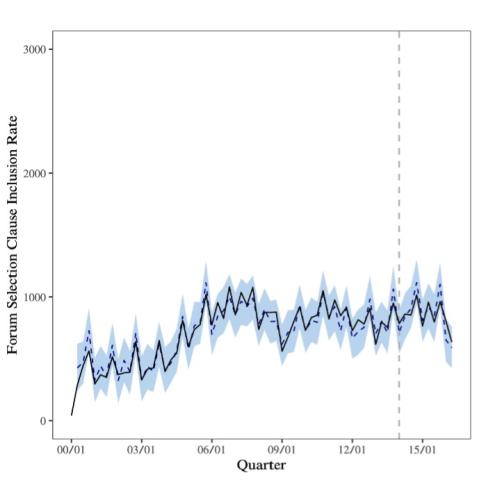

Figure 1: Dispute Resolution Clauses over Time

Figure 1 plots the use of different types of dispute resolution clauses (DRC) over time.114 It shows that contracts became more likely to include dispute settlement provisions over the years. However, there is a difference between the propensity to include a forum selection clause (FSC)—referring parties to courts—and arbitration clauses. In particular, the higher propensity to include dispute resolution clauses is exclusively driven by the increased presence of clauses referring parties to courts. In contrast, arbitration clauses became less common over time. This finding contradicts some of the claims found in the literature contending that arbitration is becoming increasingly popular.115

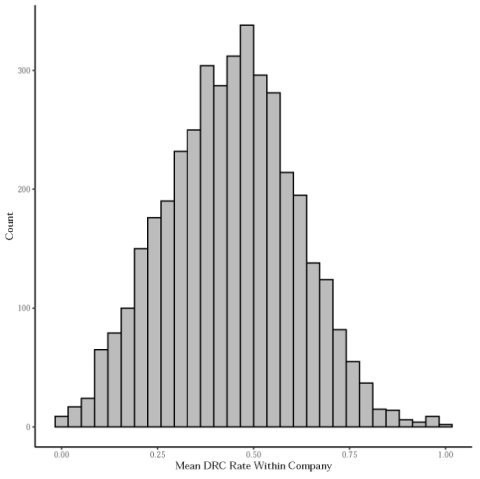

Next, it is useful to examine the internal consistency of companies using dispute settlement provisions. If companies adopt firm-wide policies on the use of these clauses, we would expect many companies to consistently include them in their contracts. To examine whether this is the case, for each company in the data set, I collect all of its agreements and compute the average occurrence of dispute resolution clauses. The resulting number reflects how internally consistent companies are in their use of dispute settlement provisions. For instance, if company i has an average rate of 0.95, it means that 95% of agreements to which company i is a party include dispute settlement provisions.

Figure 2: Internal Company Consistency

Figure 2 shows a histogram depicting where between 0 and 1 the mean usage rate lies for all companies in the data set. What can be seen is that the consistency measure is almost normally distributed around 0.5. This indicates that most companies sometimes use dispute settlement provisions while at other times omitting them. There are only very few companies that consistently include dispute resolution clauses, which is indicated by the fact that almost no company has a mean usage rate that is anywhere close to 1. Overall, the data suggest that the vast majority of companies lacks a coherent and widely enforced policy on the inclusion of dispute settlement provisions.

|

Industry |

Obs. |

Freq. |

FSC |

Arb. |

DRC |

CoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Agriculture |

13 |

0.00 |

0.23 |

0.38 |

0.54 |

0.85 |

|

Services |

99,596 |

0.20 |

0.32 |

0.21 |

0.46 |

0.75 |

|

Other |

9,360 |

0.02 |

0.33 |

0.18 |

0.46 |

0.83 |

|

Mining |

31,451 |

0.06 |

0.32 |

0.18 |

0.44 |

0.77 |

|

Transportation |

45,472 |

0.09 |

0.31 |

0.18 |

0.43 |

0.74 |

|

Manufacturing |

175,413 |

0.35 |

0.30 |

0.19 |

0.43 |

0.73 |

|

Trade |

40,671 |

0.08 |

0.30 |

0.18 |

0.43 |

0.75 |

|

Finance |

100,608 |

0.20 |

0.28 |

0.19 |

0.42 |

0.77 |

|

Construction |

5,268 |

0.01 |

0.30 |

0.15 |

0.41 |

0.74 |

Table 2 breaks down the prevalence of dispute resolution clauses by industry.116 Most of the contracts in the sample come from the manufacturing industry, followed by the finance industry and the service industry. What can be seen is that the agricultural industry is the only industry where dispute resolution clauses are more likely to be included than not included. However, with only thirteen observations, these numbers are not particularly reliable. In all other industries, fewer than half of the contracts analyzed contained a dispute settlement provision (between 41% and 46%), even though one is very likely to find a governing law clause in contracts across all industries (between 73% and 85%). Throughout all industries, arbitration clauses are relatively rare, with choice-of-forum clauses dominating the landscape of dispute settlement provisions.

|

Type |

Obs. |

Freq. |

FSC |

Arb. |

DRC |

CoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M&A |

62,839 |

0.12 |

0.53 |

0.23 |

0.64 |

0.89 |

|

Joint Venture |

1,399 |

0.00 |

0.26 |

0.44 |

0.61 |

0.74 |

|

Licensing |

9,431 |

0.02 |

0.32 |

0.39 |

0.61 |

0.80 |

|

Loan |

57,086 |

0.11 |

0.53 |

0.10 |

0.58 |

0.80 |

|

Sales |

15,898 |

0.03 |

0.37 |

0.21 |

0.50 |

0.78 |

|

Security |

21,084 |

0.04 |

0.44 |

0.09 |

0.49 |

0.82 |

|

Employment |

108,313 |

0.21 |

0.23 |

0.33 |

0.49 |

0.75 |

|

Consulting |

7,860 |

0.02 |

0.25 |

0.28 |

0.48 |

0.78 |

|

Other |

42,391 |

0.08 |

0.37 |

0.15 |

0.47 |

0.81 |

|

Transportation |

1,313 |

0.00 |

0.30 |

0.24 |

0.47 |

0.70 |

|

Lease |

16,076 |

0.03 |

0.21 |

0.27 |

0.40 |

0.66 |

|

Negotiable |

14,024 |

0.03 |

0.36 |

0.05 |

0.39 |

0.81 |

|

Legal |

10,002 |

0.02 |

0.30 |

0.11 |

0.38 |

0.71 |

|

Incentives |

140,136 |

0.28 |

0.12 |

0.11 |

0.21 |

0.64 |

Breaking contracts down by agreement type, as in Table 3, paints a somewhat different picture. M&A, joint venture, licensing, loan, and sales agreements are more likely than not to include a dispute resolution clause. At the same time, contracts providing incentives to key employees, such as employee stock option plans, pension plans, and ‘‘golden parachute” agreements are the least likely to include a dispute resolution clause. While caution is advised when interpreting descriptive statistics, these findings are at least consistent with the idea that contracts of great economic importance are more likely to be carefully drafted by parties making a greater effort to anticipate contingencies.

The descriptive statistics are also consistent with isolated findings in the literature on the relevance of dispute settlement clauses in specific settings. For instance, it has previously been argued that contracts over innovative goods—among them, joint venture and licensing agreements—are particularly sensitive to the issue of legal enforcement due to a high level of dependence on injunctive and emergency relief.117 For M&A, it has been argued that the close entanglement of contract law with corporate, securities, and antitrust law provides incentives for parties to pay especially close attention to harmonizing the legal framework surrounding their deal. In effect, this often means that forum selection clauses refer disputes to Delaware.118

|

Forum |

Mean FSC |

Mean CoL |

Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

|

New York |

0.37 |

0.26 |

0.91 |

|

Delaware |

0.11 |

0.15 |

0.89 |

|

California |

0.08 |

0.09 |

0.87 |

|

Texas |

0.05 |

0.05 |

0.89 |

|

Florida |

0.03 |

0.03 |

0.91 |

|

Illinois |

0.03 |

0.02 |

0.89 |

|

Nevada |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.92 |

|

New Jersey |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.94 |

|

Massachusetts |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.92 |

|

Pennsylvania |

0.02 |

0.02 |

0.86 |

|

Ohio |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.89 |

|

Colorado |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.88 |

|

Minnesota |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.84 |

|

Georgia |

0.01 |

0.02 |

0.91 |

|

Virginia |

0.01 |

0.01 |

0.80 |

Next, Table 4 depicts how frequently different court forums are chosen.119 Consistent with previous findings in the literature,120 New York is by far the most popular forum, with 37% of forum selection clauses referring parties to New York courts. It is commonly assumed that the reason for this dominance is the high level of expertise New York courts have in adjudicating complex commercial disputes.121 In addition, most large law firms are headquartered in New York, and economies of scale incentivize attorneys interested in practicing business law to seek admission to the New York bar, making it an unsurprising primary choice for dispute settlement. Other popular forums include Delaware (11%), California (8%), and Texas (5%).

If a contract includes both a choice-of-forum and a choice-of-law clause, parties consistently match the substantive law to the forum. This finding confirms interviews conducted by Professors Matthew Cain and Steven Davidoff in which lawyers stated that their primary concern in drafting these clauses is to avoid an incoherence between the law governing the contract and the forum that interprets it.122

Consider now the question of which law firm assisted in drafting a contract. While contracts often do not name a law firm responsible for drafting the agreement, there are many instances in which they do. Typically, the drafting law firm is disclosed in the notice clause, which requires a copy of any written communication relating to the contract to be submitted to the counsel that assisted in drafting the agreement. Other instances in which law firms appear include fee shifting clauses—when one party agrees to pay for the administrative costs of the other’s counsel—or clauses stating where the contract will be signed, which is often in one of the advising law firm’s offices. I exploit this fact using a list of 7,708 law firms with at least 50 employees, collected through LexisNexis Academic, to identify the external counsel involved in the drafting of an agreement. This approach successfully identifies participating law firms for 105,746 contracts. It is important to note that this is not a random sample of all contracts. Contracts identifiably drafted by law firms tend to be longer and more likely to include dispute settlement provisions and choice-of-law clauses than the average contract.123

|

Law Firm |

# Contracts |

FSC |

Arbitration |

DRC |

CoL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Latham & |

4,995 |

0.65 |

0.25 |

0.76 |

0.97 |

|

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP |

4,833 |

0.69 |

0.27 |

0.82 |

0.97 |

|

Kirkland & Ellis LLP |

3,362 |

0.64 |

0.22 |

0.73 |

0.97 |

|

Simpson Thatcher & |

3,232 |

0.71 |

0.21 |

0.81 |

0.97 |

|

Greenburg |

2,625 |

0.68 |

0.20 |

0.77 |

0.95 |

|

Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP |

2,310 |

0.73 |

0.21 |

0.81 |

0.96 |

|

Shearman & Sterling LLP |

2,118 |

0.65 |

0.15 |

0.72 |

0.98 |

|

Vinson & Elkins LLP |

2,084 |

0.66 |

0.23 |

0.76 |

0.97 |

|

Jones Day |

2,044 |

0.74 |

0.24 |

0.82 |

0.94 |

|

Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati |

2,008 |

0.68 |

0.31 |

0.79 |

0.96 |

|

Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz |

1,868 |

0.74 |

0.21 |

0.83 |

0.96 |

|

DLA Piper LLP (US) |

1,819 |

0.70 |

0.27 |

0.82 |

0.95 |

|

Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP |

1,813 |

0.78 |

0.14 |

0.81 |

0.97 |

|

Sidley Austin LLP |

1,798 |

0.73 |

0.23 |

0.79 |

0.97 |

|

Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP |

1,775 |

0.64 |

0.28 |

0.74 |

0.96 |

|

Mayer Brown |

1,771 |

0.68 |

0.17 |

0.74 |

0.95 |

|

Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP |

1,764 |

0.67 |

0.26 |

0.78 |

0.97 |

|

Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP |

1,698 |

0.82 |

0.14 |

0.85 |

0.97 |

|

Ropes & Gray LLP |

1,694 |

0.64 |

0.19 |

0.72 |

0.96 |

|

Cahill Gordon & Reindel LLP |

1,657 |

0.72 |

0.07 |

0.74 |

0.98 |

|

Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP |

1,596 |

0.65 |

0.26 |

0.77 |

0.96 |

|

Sichenzia Ross Friedman |

1,580 |

0.74 |

0.16 |

0.82 |

0.96 |

|

O’Melveny & Myers LLP |

1,506 |

0.60 |

0.30 |

0.77 |

0.96 |

|

Paul Hastings LLP |

1,501 |

0.70 |

0.28 |

0.81 |

0.95 |

|

Morrison & Foerster LLP |

1,453 |

0.68 |

0.26 |

0.79 |

0.96 |

|

Sullivan & Cromwell LLP |

1,433 |

0.73 |

0.22 |

0.82 |

0.97 |

|

White & Case LLP |

1,414 |

0.73 |

0.21 |

0.82 |

0.96 |

|

Goodwin |

1,351 |

0.69 |

0.29 |

0.80 |

0.96 |

|

Bingham McCutchen LLP |

1,302 |

0.66 |

0.21 |

0.75 |

0.95 |

|

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, |

1,295 |

0.74 |

0.21 |

0.82 |

0.97 |

Table 5 depicts the thirty most frequently relied upon law firms. By far the most contracts are drafted by Latham & Watkins and Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP, with 4,995 and 4,833 contracts, respectively. Choice-of-law clauses are almost universally adopted, with most law firms including them in over 96% of their contracts. Dispute resolution clauses are less common, with most law firms including them in 70–80% of contracts.124 One notion, consistent with the finding that both choice-of-law and dispute settlement provisions are more likely in contracts in which the drafting firm can be identified, is that the supervision of external counsel decreases, but does not reduce to zero, the probability for a contractual gap. Another theory consistent with this finding is that lawyers are used in more complex transactions, and that in complex transactions, all participants are more mindful of the issue of forum choice.

Lastly, I identify the particular counsel responsible for drafting the agreement. Similar to the identity of the drafting law firm, notice clauses typically specify the individuals the notices should be addressed to. I parse the notice clauses from the contracts using regular expressions and then perform a task known as “Named Entity Recognition” to extract personal names from the notice clauses.125 Overall, this process identifies 53,952 names in 73,701 contracts.

To summarize, for each material contract, the data set includes (1) information on contract characteristics, such as the type of the contract, its length and the year it has been filed; (2) information on the drafting parties, such as their Central Index Key, their industry, and their place of incorporation; (3) information on the choice-of-law and dispute settlement provisions in the contracts, including whether and where the parties opt for litigation and arbitration; and (4) the identity of the lawyers and law firms that assisted in drafting the agreement, if available.

IV. Law Firm Influence

Having thus compiled the data set, I proceed with the first test, examining if and to what extent the decision to include, or not to include, a dispute settlement provision is influenced by external counsel.

Figure 2 above shows that companies seem to lack firm-wide policies on dispute resolution clauses. Instead, most firms sometimes include, and sometimes do not include, these provisions. Because the identity of the company does not seem to induce consistency, it seems theoretically plausible that external counsel has ample room to determine independently whether a contract should specify the dispute settlement mechanism.

A. Main Analysis

In deriving a test that investigates law firm influence on the presence of dispute resolution clauses, consider the following analytical approach: Assume we have four similar contracts, A, B, C, and D. Contracts A and B are drafted by the same law firm, whereas contracts C and D are drafted by different law firms. Then we can assess the influence of the actors on dispute resolution provisions with the following three-step process:126

- Compute the difference in dispute resolution clause usage between contracts A and B.

- Compute the difference in dispute resolution clause usage between contracts C and D.

- Compare the quantity computed under (1) to the quantity computed under (2).

If law firms have an influence on whether a contract includes a dispute settlement provision, then, in the aggregate, the probability that two contracts both include the same dispute resolution clause should be high when the law firms are the same (quantity under step one) and smaller when the law firms are different (quantity under step two).127 A similar rationale applies to in-house counsel, allowing one to compare the influence of internal legal advisers to that of the law firms.

The main challenge in implementing this procedure is to guarantee that contracts A, B, C, and D are, in fact, similar. This is no easy feat. Indeed, contracts in the data set differ in a variety of ways, such as in the companies that are party to the agreement, the industry, or the contract type. If left unaddressed, it is at least possible that the difference between two contracts is caused by factors other than the law firm.

In order to ameliorate concerns arising out of this form of omitted variable bias, I employ matching to create pairs of company contracts. Matching is a popular method in the social sciences and causal inference that seeks to pair two units that look similar on a number of dimensions, with the only observable difference being the variable of interest.128 Among the different matching algorithms, exact matching is the most restrictive, as it requires each pair of observations to be exactly the same across all characteristics. This has advantages and disadvantages. The main disadvantage is that an exact-matching algorithm omits a lot of data, as pairs that are even slightly dissimilar are removed. However, in very large data sets such as this one, omitting data is not a primary concern as long as reliable standard errors can be obtained. The main advantage of exact matching is that it is able to achieve perfect homogeneity across all observed characteristics, making both contracts highly comparable on these observed dimensions.

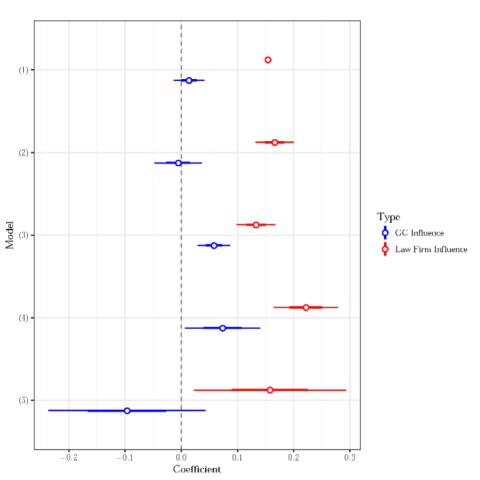

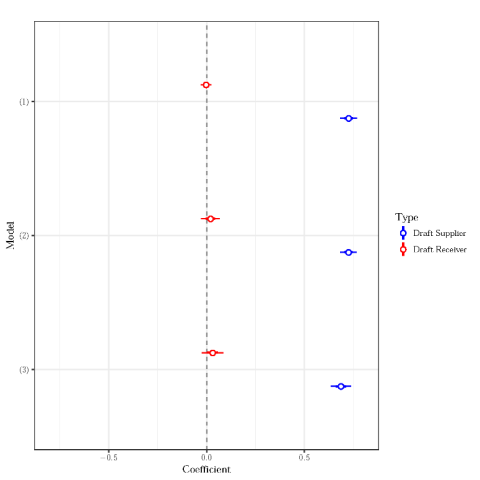

Having created matched pairs of similar contracts in this way, I use OLS regression to investigate the average law firm influence on the presence of dispute resolution clauses.129 I then do the same for general counsel influence. The results are presented in Figure 3.130 Each row in the plot corresponds to a different model and contains two dots. The red dots indicate a lower bound on the law firm’s influence on dispute settlement provisions in the contract.131 For instance, a dot at 0.1 suggests that a change in law firms is associated with at least a ten percentage point increase in the probability to encounter one contract with and one without a dispute settlement provision. The blue dot depicts the lower bound on the influence of the general counsel.

The red and blue lines depict 95% confidence intervals and can be thought of as a certainty measure. If the confidence intervals include the dotted line at zero, this suggests that that law firms or general counsel may have no impact on the prevalence of dispute settlement provisions. If it does not include zero, by conventional measures, the influence is statistically significant.132

Figure 3: Law Firm and General Counsel Influence on Dispute Resolution Clauses

Model (1) only matches on parties and provides a baseline. Model (2) only includes contract pairs where—in addition to the parties—the format, type, and industry of the agreements in the pair are identical, i.e., matched pairs. It further controls for the contract type, format, and industry through the inclusion of fixed effects.133 It also controls for the difference in years in which the contracts were reported. The resulting analysis guarantees that contracts are highly comparable on the observed dimensions. Model (3) adds party-pair fixed effects to control for unobserved, party-pair specific characteristics.

The results are striking. The probability for two contracts to differ is between thirteen and twenty-three percentage points if both agreements were drafted by the same law firm.134 If law firms change, depending on the model specification, the probability increases by fifteen to twenty-three percentage points. In relative terms, this is an increase of about 100%. Meanwhile, most specifications suggest that the general counsel has no discernable influence on whether a contract includes a dispute resolution clause. And even when the coefficient is statistically significant, it is small, with a difference of six percentage points.

Model (4) investigates the law firm and general counsel influence not on the presence of a choice-of-forum provision, but on the specific jurisdiction parties specify in their clause.135 Model (5) analyzes the influence on the particular arbitral institution that parties opt for. Both models yield generally consistent results with the other specifications.

B. Identification Through Law Firm Closure

The preceding analysis suggests that law firms have a large influence on the presence of dispute resolution provisions, whereas there is no consistent evidence that the general counsel is a significant actor. However, we need to exert caution in interpreting these estimates causally. For one, while matching guarantees that the contracts in each pair look identical on all observed characteristics, it is possible that unobserved characteristics, such as the transactional value, still govern which law firm is hired, as well as whether a dispute resolution clause is included. Hence, the presence of omitted variable bias cannot be ruled out with certainty.