Exporting American Discovery

This Article presents the first comprehensive study of an intriguing and increasingly pervasive practice that is transforming civil litigation worldwide: US judges now routinely compel discovery in this country and make it available for disputes and parties not before US courts. In the past decade and a half, federal courts have received and granted thousands of such discovery requests for use in foreign civil proceedings governed by different procedural rules. I call this global role played by US courts the “export” of American discovery.

This Article compiles and analyzes a dataset of over three thousand foreign discovery requests filed between 2005 and 2017 under 28 USC § 1782—an expansive statute that is now the pivotal law governing the export of American discovery. I use the dataset to show that the foreign civil demand for US discovery has approximately quadrupled during the study period, that demand from foreign private actors now overshadows demand from foreign tribunals, and that the requests’ countries of origin have diversified. I then map the ways in which the machinery of domestic discovery is distorted in the context of global discovery, leading to missing foreign stakeholders and systematic bias toward compelling discovery. Reflexively exporting US discovery, in turn, undermines Supreme Court doctrine, risks imposing unintended externalities on foreign tribunals and foreign litigants, and erodes universal notions of fairness and due process.

Although foreign discovery requests account for a small fraction of federal dockets, they provide an illustrative case study of the larger phenomenon of disputes straddling multiple legal systems. Litigants and attorneys are now strategizing across borders and deploying national procedural tools to their global advantage. Yet, judges continue to operate within national silos even as they play a global role. Consequently, judges are at an informational disadvantage when they adjudicate disputes only parts of which are before them. This contemporary challenge calls for institutional solutions in the form of court-to-court information sharing and coordination across borders, as well as a reconceptualization of federal judges as global actors who share overlapping authority with foreign judges and arbitrators.

“A curious quirk of our law is that American courts are not limited to American disputes.”

–Then–Magistrate Judge Paul Singh Grewal, Northern District of California1

“[T]he obvious question is well, why, don’t they have access to that discovery vehicle in Argentina, why do they need access to this little Reno office[?]”

–Then–Chief Judge Robert C. Jones, District of Nevada2

Introduction

Across the country, federal courts now routinely have a hand in the resolution of foreign civil disputes. They do so by compelling discovery in the United States—typically as much discovery as would be available for a lawsuit adjudicated in federal district court—and making it available for use in foreign civil proceedings3 governed by different procedural rules. In the past decade and a half, federal courts have received and granted thousands of such discovery requests.4 They come from foreign courts and foreign parties.5 They seek discovery for cases ranging from billion-dollar environmental controversies6 to the dissolution of marriages,7 and in countries as varied as Chile,8 Romania,9 Iran,10 and South Korea.11 Since most of these requests are decided in low-profile, unpublished orders buried in federal dockets around the country, they have received little systematic attention from scholars despite their transformative impact on the practice of global litigation.12 Nearly every major law firm and numerous smaller ones now advise clients and strategize around the availability of compelled discovery in the United States for use abroad.13 Practitioners consider this feature of US law “an invaluable tool,”14 “a powerful strategic advantage,”15 and “a back door” for foreign litigants16 that parties ignore “at their peril.”17

I call this growing global role played by US courts and judges the “export” of American discovery.18 In today’s globalized world, disputes increasingly cannot be confined to one legal system alone. The fact that evidence relevant to a foreign dispute might be located in and exported from the United States is a symptom and symbol of this modern reality. The export of American discovery provides an illustrative case study of the institutional challenges that arise when disputes straddle contrasting legal systems. For what is being exported is not just information—typically in the form of witness testimony or the production of documents—that may be submitted as evidence before a foreign tribunal. Along with that information comes the compulsory power of US courts and a set of procedures and litigation values found virtually nowhere else in the world.

American civil procedure is well recognized as being exceptional.19 Discovery in US federal courts is “far broader” in scope than in other countries20 and is primarily conducted and controlled by the parties, rather than by judges.21 Expansive discovery is central to American litigation, and is intertwined with the very mission of government in American society—one that is more “reactive” and plays a smaller ex post role resolving disputes, rather than a larger ex ante role implementing state programs.22 Outside the United States—where litigation may perform a different function in regulating society—American discovery is regarded as excessive and has been approached with skepticism and animosity.23

Operating across different discovery systems offers private actors opportunities for arbitrage. Seeking US discovery is typically straightforward. One files a request with the federal district court where the discovery target is located. That request is usually entertained and granted with minimal judicial activity and on an ex parte basis—without the participation of the foreign opposing party or the foreign tribunal before which the discovery is to be used. The target of the request is then subpoenaed and ordered to produce discovery according to the scope and practices of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure (FRCP). The target might happen to be the foreign opposing party or might choose to voluntarily alert the foreign opposing party, who might in turn inform the foreign tribunal, but that does not always happen. The foreign opposing party and the foreign tribunal might never know that one side of the case was built using different discovery practices than those governing the remainder of the dispute.

These requests generate complications for both the foreign opposing party and the foreign tribunal. Take the example of a discovery request filed in the Northern District of Alabama by a private actor seeking discovery from a US bank for a contemplated lawsuit in the British Virgin Islands.24 Such prefiling discovery requests are permitted under 28 USC § 178225 —an expansive federal statute written in the 1960s that is now the pivotal law governing the export of discovery. The request was initially granted ex parte and a subpoena was served on the bank, which was not a party to the contemplated suit. Months after the request was granted and the subpoena served, the anticipated opposing party moved to intervene, arguing denial of due process because the company was never informed of the request at the time the court considered it. In fact, similar discovery requests had been made in three additional US district courts without alerting the opposing party.26 The Northern District of Alabama nevertheless declined to vacate the discovery order.27 This fact pattern is common, and there is no effective procedural mechanism for ensuring symmetrical discovery when one side benefits from broad US discovery while the other is limited to the more restrictive procedures of the foreign tribunal.

Consider also the example of the European Commission filing an amicus brief before the US Supreme Court in 2003 to prevent a district court in the Northern District of California from compelling the production of evidence, ostensibly in its aid.28 At the time, the European Commission was investigating an antitrust complaint brought by Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) against its worldwide competitor, Intel.29 When the Commission declined AMD’s suggestion that it seek certain documents from Intel, AMD asked the Northern District of California, the jurisdiction where Intel is headquartered, to subpoena Intel for that same information.30 The request eventually reached the Supreme Court, where the European Commission argued that granting AMD’s request in the United States would be a “direct interference” with the Commission’s own “orderly process” and would undermine its policies, increase its workload, and divert its enforcement resources.31 The Commission protested: “[we do not] want to be used as a pawn by . . . private entities seeking to employ [American] processes . . . to obtain . . . discovery that’s available under no other circumstances.”32

These two cases illustrate the consequences that American discovery can have for foreign courts and foreign parties—consequences that were not intended by Congress or by the Supreme Court. When Congress first enacted § 1782 in its current form, it believed the statute to be “the kind of assistance that is likely to be preferred abroad,”33 and advised federal courts to consider the “character” of the foreign proceeding and the “nature and attitudes” of the foreign country and tribunal.34 When the Supreme Court took up the dispute between Intel and AMD, it further directed district courts to avoid offense to foreign courts and to maintain an appropriate level of parity between foreign litigants.35 Based on factors set out by the Court,36 the Northern District of California denied AMD’s discovery request on remand, given the European Commission’s expressed rejection of US discovery.37

Yet, the export of American discovery has also been described as “legal imperialism”38 and “officious intermeddl[ing].”39 And this Article’s empirical and doctrinal analyses confirm that federal judges are not able to apply the Supreme Court’s instructions in practice. Some pinpoint the problem as § 1782’s conferral of broad discretion on federal judges,40 though there is much disagreement over how that discretion should be narrowed.41 Others contend that the export of American discovery violates the separation of powers in the United States,42 and that it is a unilateral fix for a set of issues that call for a multilateral solution.43 While a treaty governing the international exchange of evidence—the Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters (“Hague Evidence Convention”)—was signed in 1970,44 it is widely considered to be ineffective,45 leading some to demand further efforts to forge procedural uniformity across nations46 and others to bemoan the futility of seeking convergence given the vast procedural differences worldwide.47 Needless to say, there is no consensus on whether the export of American discovery is working, and, if not, where the problems lie and what an alternative system for sharing evidence would look like.

I argue that the export of American discovery is in need of reform. Its most pressing shortcoming is its failure to include and to provide due process to the appropriate actors. When discovery is exported, it has ripple effects for foreign adversaries against whom the evidence is to be used, and for the foreign tribunal overseeing the dispute. Yet, there is no established mechanism for informing or involving those entities. Instead, federal judges have remained at arm’s length from the very foreign proceedings they are influencing, and have engaged in the impossible task of abstractly weighing foreign interests with no foreign input. The problem, therefore, is not an excess of discretion, but a shortage of information. This problem can be addressed in the immediate term through shifts in judicial practice, and in the medium term through changes to the FRCP and amendments to § 1782. In the long term, a broader reconceptualization of the global role played by federal judges—and the global space in which they operate—is needed.

This Article proceeds in four Parts. Part I describes the centrality of § 1782 to the export of discovery. The statute allows foreign tribunals and foreign private actors to seek US discovery directly from federal district courts. In interpreting the statute, the Supreme Court instructed district courts to consider a foreign tribunal’s need for and receptivity to US discovery, and to maintain an appropriate measure of parity between the parties.48 The statute’s implementation by lower courts is now fractured along many lines, exposing confusion surrounding the statute’s purpose and scope, as well as its intended effect on foreign tribunals and the parties before them.

Part II provides a comprehensive, nationwide, descriptive account of how foreign discovery requests have operated in district courts. I compiled a dataset of over three thousand foreign discovery requests filed under § 1782 between 2005 and 2017, approximately two thousand of which are for use in civil proceedings abroad. Relying on the dataset, I show that the foreign civil demand for US discovery has approximately quadrupled in that time, and that their countries of origin have diversified. Demand from foreign parties now overshadows demand from foreign tribunals, with private actors making more complex and creative strategic uses of US procedures across borders. Overall, the grant rate is very high (94 percent in 2015) while the contestation rate is relatively low (22 percent in 2015), calling into question whether US judges are serving as effective discovery gatekeepers for disputes in foreign tribunals.

Part III performs a doctrinal evaluation of the export of American discovery and concludes that US judges are at a severe informational disadvantage when fielding requests from foreign parties. It is assumed that the machinery of domestic discovery can be extended to exported discovery, but the discretion and expertise exercised by federal courts in the domestic context cannot be transferred to discovery requests from foreign parties due to the absence of critical actors and the lack of relevant information. Consequently, federal judges have devised shortcuts for the analyses they conduct, which in turn place a heavy thumb on the scale for granting discovery. Those shortcuts not only undercut congressional intent and the Supreme Court’s interpretation of § 1782, but also pose larger normative problems by eroding comity, adverseness, and basic notions of due process and fairness. By contrast, the discretion and expertise exercised by federal courts in the domestic context is inapposite for discovery requests from foreign tribunals, the vast majority of which are governed by treaty.

Part IV proposes several reforms. I advocate for more active judicial management of § 1782 requests that systematically seeks out the participation of foreign opposing parties and foreign tribunals. I also recommend restructuring § 1782 requests so that each foreign discovery request is no longer filed as a stand-alone US case—a feature that makes these requests uniquely difficult to administer.

Finally, I conclude that this study of § 1782 and its unaccounted-for foreign impacts suggest broader challenges that courts face when disputes straddle multiple legal systems. Litigants and attorneys are adapting to the transnational nature of litigation by strategizing across borders and deploying national procedural tools to their global advantage. Meanwhile, judges are increasingly at an informational disadvantage as they continue to operate within national silos, adjudicating disputes, only parts of which are before them. These challenges call for institutional solutions in the form of court-to-court information sharing and coordination across borders, as well as a shift toward reconceptualizing federal judges as global actors who share overlapping authority with foreign judges and arbitrators.

I. The Mechanics of Export

This Part sets out the mechanics, governing laws, and institutional actors engaged in the export of discovery. The United States has been offering some form of exported discovery since the mid-nineteenth century. Today, 28 USC § 1782 is the key governing statute. It provides the broadest and most direct access to US discovery, and it is also used internally by the Department of Justice to execute discovery requests made through two indirect routes—the traditional system of letters rogatory and the Hague Evidence Convention. This Part describes the three existing paths to US discovery, highlights the centrality of § 1782, and examines the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the statute.

A. Three Paths to US Discovery

1. Letters rogatory.

The traditional “letter rogatory”—a formal request to perform a judicial act sent from the court of one country, typically through diplomatic channels, to the court of another country49 —is the oldest mechanism for obtaining discovery assistance in the United States.50 It continues to operate today, with the Department of State and Department of Justice acting as intermediaries for executing them.51 Internationally, letters rogatory are fulfilled on a discretionary basis and as a matter of international comity.52 Domestically, they are accorded the same more favorable treatment as requests made under the Hague Evidence Convention,53 described below.

Because letters rogatory originate with a request from a foreign court (rather than a party to a foreign suit), the receptivity of that court to US discovery assistance is assured. Letters rogatory have been criticized for being unwieldy, time-consuming, and costly.54 They typically travel from the requesting court in a foreign country, to that country’s ministry of foreign affairs, then to that country’s embassy in the United States,55 then to the US Department of State, and then to the Office of International Judicial Assistance (OIJA) in the Department of Justice. OIJA screens the request for straightforward technical requirements, attempts to secure the requested discovery voluntarily, and in the absence of voluntary compliance, submits the request to a district court,56 which then relies on § 1782 for execution. Once compelled, the discovery travels back to the requesting court via the same path. The State Department estimates that this process can take a year or more and recommends use of more “[s]treamlined procedures,” such as an international treaty or a direct petition to a court, when possible.57

2. 28 USC § 1782.

During the years following World War II, a surge in international business and other cross-border activities led to a “flood of litigation” in the United States with international elements.58 American lawyers, frustrated by procedural differences between the United States and the civil law countries of Europe and Latin America, called for “a modernization of international legal procedure.”59 With the adoption of the FRCP in 1938, American lawyers were accustomed to a liberal, party-driven system of discovery aimed at uncovering the “fullest possible knowledge of the issues and facts before trial.”60 Yet, in other countries they were forbidden from taking evidence directly,61 and had to rely on letters rogatory, which they found to be “inefficient, time consuming, and costly.”62 Some jurisdictions, like Germany and the Netherlands, would not compel the testimony of unwilling witnesses even when a letter rogatory was issued.63 And testimony secured through a letter rogatory might not be usable in the United States due to noncompliance with domestic requirements such as examination under oath and oral questioning by an attorney.64

Congress enacted a number of measures to address these challenges. To facilitate the import of discovery, Congress authorized federal courts to subpoena and to hold in contempt an American citizen or resident in a foreign country.65 The FRCP were revised to specify how testimony could be taken abroad,66 and permitted district courts to order the production of documents, regardless of location, so long as they are in the “possession, custody, or control” of a party to a US proceeding or a nonparty witness over whom the court has jurisdiction.67

To facilitate the export of discovery, Congress passed 28 USC § 1782 in 194868 and rewrote it in 1964.69 The statute reads:

The district court of the district in which a person resides or is found may order him to give his testimony or statement or to produce a document or other thing for use in a proceeding in a foreign or international tribunal. . . . The order may be made pursuant to a letter rogatory issued, or request made, by a foreign or international tribunal or upon the application of any interested person and may direct that the testimony or statement be given, or the document or other thing be produced, before a person appointed by the court. . . . The order may prescribe the practice and procedure, which may be in whole or part the practice and procedure of the foreign country or the international tribunal, for taking the testimony or statement or producing the document or other thing. To the extent that the order does not prescribe otherwise, the testimony or statement shall be taken, and the document or other thing produced, in accordance with the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.70

In 1996, the statute was revised to include discovery for use in criminal investigations71 —a subject beyond the scope of this Article.

At the time of the 1964 revision, the statute was considered “a major step in bringing the United States to the forefront of nations.”72 It was thought to provide “equitable and efficacious procedures” for foreign tribunals and litigants, and to meet the “requirements of foreign practice and procedure.”73 Congress hoped that foreign countries would reciprocate by providing US litigants with easy access to foreign discovery.74 Despite these aspirations, many have observed that foreign countries have not in fact reciprocated.75

3. Hague Evidence Convention.

While these domestic policies were being put into place, it was also recognized that the problems arising from international litigation needed an international response. During the late 1960s, the United States led the negotiations for the Hague Evidence Convention, which was adopted in 1970 and entered into force for the United States in 1972.76 It operates through “Letters of Request,” which are issued by the judicial authority of one contracting state to the designated “Central Authority” of another, and then to the proper domestic authority for execution.77 Within the United States, OIJA serves as the Central Authority.78 Once a request reaches OIJA, it is carried out in the same way regardless of whether it is a request under the Hague Evidence Convention or a letter rogatory from a non-Convention country.79 OIJA screens the request, attempts to secure the evidence voluntarily, and then forwards the request to the appropriate federal district court for compelled discovery under § 1782.80 Since requests must originate from a foreign judicial authority (rather than from a party), receptivity of that authority to US discovery is assured.

The Convention was initially presented to the US Senate and to bar associations as requiring other countries to make concessions while not necessitating significant changes domestically given the existence of the more powerful § 1782.81 It is now in force between the United States and fifty-four countries.82 Many have commented that it has failed to achieve its intended purpose of bridging the gap between the United States and civil law countries.83 All but a handful of contracting states have adopted a declaration that they will not execute letters of request seeking pretrial discovery of documents as is common in the United States.84 Meanwhile, observing that the Convention’s procedures “would be unduly time consuming and expensive, as well as less certain to produce needed evidence than direct use of the Federal Rules,” the Supreme Court concluded in 1987 that the Convention is not the exclusive or even the required first resort procedure for American litigants seeking evidence abroad.85 Instead, a US court may continue to unilaterally compel extraterritorial discovery from those subject to its jurisdiction86 —a practice resented by foreign countries.87 There remains no effective international agreement governing discovery across borders, and some suggest that the United States should denounce the Hague Evidence Convention.88

B. The Centrality of 28 USC § 1782

These three paths to US discovery now overlap. A foreign tribunal seeking discovery in the United States may either use letters rogatory, the indirect path of the Hague Evidence Convention, or the direct path of § 1782. Similarly, a foreign private actor may either indirectly ask the relevant foreign tribunal to send a request, or directly request it from a federal district court under § 1782, bypassing the foreign tribunal and other intermediary national authorities. Within the United States, all requests are ultimately executed by federal district courts under § 1782.89 Section 1782’s statutory language does not differentiate between direct requests and indirect requests, or between requests from foreign tribunals and those from foreign private actors.

Direct requests from foreign private actors have caused the most complications and are the source of nearly all appeals in the past decade.90 Some scholars argue that permitting private actors to access US discovery was a “dramatic departure” from the traditional notion that judicial assistance is provided by one court to another.91 In particular, courts have struggled with the question of how they should weigh a foreign tribunal’s receptivity to US discovery. Section 1782’s statutory language does not shed light on this question, but the statute’s legislative history notes that federal district courts should consider “the nature and attitudes of the government of the country from which the request emanates and the character of the proceedings in that country” when granting or denying a § 1782 application.92

In 2004, the Supreme Court considered whether sought-after discovery must be discoverable abroad for it to be discoverable under § 1782—a shorthand for determining receptivity that had been adopted by some courts.93 The Supreme Court rejected the foreign discoverability requirement in Intel Corp v Advanced Micro Devices, Inc,94 a case in which the discovery sought by a private actor under § 1782 was not discoverable abroad and expressly not wanted by the foreign tribunal at issue: the European Commission.95 The Commission filed an amicus brief explaining that the discovery would give AMD access to documents it is not permitted to review under European law, would undermine the Commission’s policies on confidential information, and would increase its workload and divert its enforcement resources.96 Section 1782, the Commission argued, could “become a threat to foreign sovereigns if interpreted expansively.”97 Several industry associations filed amicus briefs expressing concern that compelling discovery under § 1782 that is not discoverable abroad could produce unfair outcomes when US-style discovery benefits one side of a dispute but not the other.98 The Department of Justice filed an amicus brief supporting a broad interpretation of § 1782 since it relies on the statute to execute letters rogatory and letters of request under the Hague Evidence Convention.99

The Supreme Court reasoned that a foreign discovery restriction does not necessarily translate into an objection to exported discovery from the United States.100 Instead, the Court enumerated four discretionary factors for district courts to consider: (1) whether the requested evidence is available without § 1782; (2) whether the foreign government or court is receptive to US federal court judicial assistance; (3) whether the request “conceals an attempt to circumvent foreign proof-gathering restrictions or other policies of a foreign country or the United States”; and (4) whether the request is unduly burdensome or intrusive.101 The Supreme Court explained that these factors, as well as the exercise of judicial discretion more generally, could safeguard comity. Similarly, parity between the foreign adversaries could be maintained either by the district court conditioning its grant of discovery, or by the foreign tribunal conditioning its acceptance of US discovery, on a reciprocal exchange of information.102 On remand, the Northern District of California denied the discovery request given the European Commission’s amicus brief expressing resistance to US discovery.103

Since the Supreme Court’s decision in 2004, lower courts’ implementation of § 1782 have continued to fracture along many lines. Most prominently, the Courts of Appeals now disagree on whether the statute can be used to compel discovery in aid of foreign commercial arbitrations. The Seventh Circuit recently held that § 1782 does not extend to private international commercial arbitrations, placing it in agreement with the Second and Fifth Circuits and in conflict with the Fourth and Sixth Circuits.104 Lower courts also disagree on whether § 1782 can be used to compel documents physically located abroad but under the possession, custody, or control of a US entity.105 Further complicating the matter, entrepreneurial litigants now use discovery obtained through § 1782 in multiple proceedings before multiple tribunals once the statute’s requirements are deemed satisfied with respect to one foreign proceeding.106 These are just a few of the developments that expose persistent confusion surrounding the statute’s purpose and scope, as well as its intended effect on foreign tribunals and the parties before them.107

II. Evidence from Federal Dockets

This Part presents the findings of the first nationwide study of foreign discovery requests in federal district courts. Despite anecdotal reports that foreign discovery requests have experienced “a groundswell of popularity,”108 there have been no attempts to systematically investigate recent trends in the overall number of requests, or their nature, origins, and outcome. I fill this gap by compiling and analyzing the most exhaustive existing dataset of requests for discovery to be used in civil disputes abroad.

The number of discovery requests for use in foreign civil proceedings received by district courts has indeed surged, approximately quadrupling between 2005 and 2017. Their countries of origin have diversified, suggesting that the historical concern about procedural differences between the United States and the civil law countries within Western Europe and South America may not be as central as it used to be. Meanwhile, there is a growing need to understand legal systems in Asia and Eastern Europe.

The vast majority of requests fall into two categories: indirect requests from foreign courts and direct requests from foreign parties. In other words, foreign parties now have a more direct relationship with US district courts than do foreign tribunals. Moreover, demand from foreign parties now overshadows demand from foreign tribunals in both number and complexity of requests. Whereas foreign tribunal requests are fairly straightforward, homogenous, and most frequently connected to family law matters, foreign party requests are more sophisticated, varied, and most frequently connected to commercial matters. These divergences suggest that there are different dynamics at play in these two sets of requests. Whether US judges are serving as effective discovery gatekeepers in each type of request is examined in the next Part.

Analysis of federal dockets is also illuminating for what it cannot reveal. Requests are typically considered ex parte, without informing or including the foreign tribunal or foreign opposing party, though occasionally notice is given in haphazard ways. For reasons explained below, it was not possible to systematically track when notification was provided to the foreign tribunal or foreign opposing party and therefore when a foreign tribunal was aware that a US discovery request had been made. Because I could not track foreign tribunal awareness of a US discovery request being made by a foreign party, it was also not possible to determine how often and which foreign courts tended to welcome or resist sought-after discovery. Finally, docket analysis provides an incomplete picture of when multiple US discovery requests are made for the same foreign proceeding, and no information about what happens after a request is granted. Federal judges make foreign discovery decisions in the absence of this information.

A. Data Overview

I compiled a dataset composed of over three thousand discovery requests, filed between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2017, seeking compelled discovery under § 1782 for use in foreign proceedings. Since § 1782 authorizes discovery requests for foreign civil and criminal proceedings, this initial dataset included both. Appendix A describes the process I used to build the dataset. Briefly, I relied on the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) system—a mandatory electronic docketing system that provides access to all actions filed in federal district courts nationwide.109 I devised a text search for identifying § 1782 requests that maximized sensitivity without significant sacrifices in specificity. I then ran the search on Bloomberg Law, which renders PACER text searchable. I manually eliminated false positives and performed several checks to ensure that the dataset is close to exhaustive and lacking in bias. I selected the time period 2005 to 2017 to capture recent trends in foreign discovery requests: 2005 is the first full calendar year after the Supreme Court decided Intel, and 2017 is the final full calendar year prior to commencement of this study. The dataset is summarized year by year in Table 5 of Appendix C. I drew a random sample of over one thousand discovery requests for more detailed analysis, also summarized year by year in Table 5.

Analysis of the sample shows that approximately one-third (919) of all requests were connected to criminal proceedings abroad (“criminal requests”), while approximately two-thirds (2,070) were connected to civil proceedings abroad (“civil requests”). Breaking down the requests by year shows that the number of civil requests has grown rapidly, approximately quadrupling between 2005 (49 requests) and 2017 (208 requests). While it is not possible to determine from docket analysis the causes of this rapid rise, there are several possible reasons for it: (1) an increase in cross-border activity leading to more disputes abroad for which evidence may be gathered in the United States;110 (2) an increase in foreign substantive laws with extraterritorial reach such that more transnational activity is subject to civil suits abroad;111 and (3) an increase in awareness and use of § 1782 by law firms, attorneys, and parties.

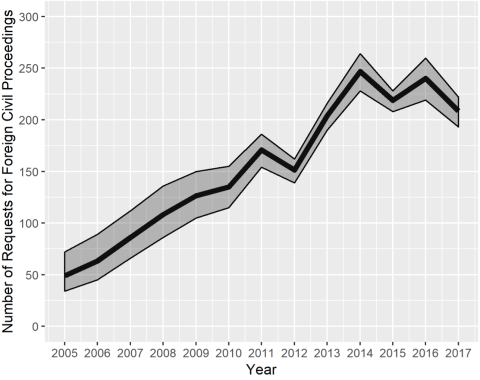

There is an inverse trend for criminal requests brought under § 1782,112 though this does not necessarily reflect an overall contraction in criminal requests due to the enactment of an overlapping federal statute in 2009.113 There is also a small number of cases every year—cumulatively more than one hundred over the study period—that are refiled under another case number due to confusion concerning the proper case type designation for foreign discovery requests.114 The rising number of civil requests, along with upper and lower bounds representing 95 percent confidence intervals, are visualized below in Figure 1 and summarized numerically in Table 6 of Appendix C.

Figure 1: Estimated Number of Civil Requests, 2005–2017115

Approximately half of civil requests are sent to the Southern District of New York, the Southern and Middle Districts of Florida, and the Northern and Central Districts of California,116 with the rest distributed across the country. Over 60 percent of district courts nationwide received at least one foreign civil discovery request during the study period.117 The remaining analyses below rely on in-depth coding of civil requests from the randomly drawn sample. Appendix B describes the methodology I used for coding.

B. Request Analysis

I examined basic characteristics of civil requests: who requested them, who they targeted, the nature of the foreign tribunal, the nature of the foreign proceeding for which they were requested, and the country of origin.

1. Requestor.

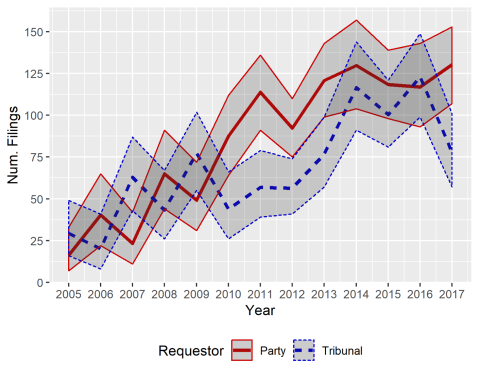

The vast majority of foreign discovery requests come either indirectly from foreign tribunals through OIJA (approximately 40 percent) or directly from foreign parties under § 1782 (approximately 55 percent). For the most part, foreign tribunals continue to seek judicial assistance indirectly through the Hague Evidence Convention and letters rogatory despite having direct access to federal courts.118 Additionally, a tiny number of requests originate from a broader class of “interested persons” (approximately 0.77 percent) who are not a party to, but have some procedural rights in, a foreign proceeding.119 These findings are summarized in Table 8 of Appendix C. Figure 2 below visualizes the increase in tribunal and party requests over time, and shows that the number of party requests has exceeded the number of tribunal requests in most recent years.

Figure 2: Estimated Number of Civil Requests from Foreign Tribunals and Foreign Parties, 2005–2017120

2. Target.

The vast majority of civil requests seek discovery from nonparties to the proceeding abroad. This is true for requests from foreign tribunals (approximately 85 percent) and foreign parties (approximately 88 percent), and remains consistent over the study period. Nonparty targets include banks, Internet and social media companies, as well as law firms. The prominence of nonparties as targets is in part because nonparties located in the United States cannot be reached by the foreign court where the case is pending, and in part because discovery targeting nonparties is favored under Intel, so it is advantageous to target a US nonparty even if a foreign party holds the same information.121 Table 9 of Appendix C provides a breakdown of requests from foreign tribunals and foreign parties by target.

3. Nature of foreign tribunal and proceeding.

Overall, requests from foreign tribunals are more homogeneous than those from foreign parties. Virtually all requests from foreign tribunals seek discovery for use in one pending litigation before a foreign court. Requests from foreign parties are more varied. The vast majority are for use before foreign courts (approximately 90 percent), but a steady number are for use in commercial arbitrations (approximately 9.9 percent) and a smaller number are for use before foreign regulatory agencies (approximately 4 percent) and investor state arbitrations (approximately 2.5 percent).122 Most party requests are for use in one foreign proceeding (approximately 72 percent) or in only pending foreign proceedings (approximately 84 percent). But nearly a third are for simultaneous use in multiple proceedings worldwide (approximately 28 percent) and a steady number are for use in contemplated foreign proceedings that are yet to be filed (approximately 15.9 percent). Tables 10 and 11 of Appendix C summarize these findings. The number of foreign party requests seeking discovery for contemplated prefiling proceedings—as well as those for multiple parallel proceedings worldwide—are increasing over time.123

There is significant breadth in the substantive merits issues in dispute in the foreign civil proceedings. Requests from foreign tribunals are concentrated primarily in family law (approximately 52 percent), followed by contract (approximately 15 percent) and employment law (approximately 12 percent). These substantive areas have remained consistently prevalent for tribunal requests over the study period.124 Requests from foreign parties are concentrated primarily in contract law (approximately 27 percent), followed by intellectual property and trade secret law (approximately 19 percent), and corporate law (approximately 12 percent). While the prevalence of contract law disputes in foreign party requests has remained consistent over the study period, the number of intellectual property and corporate law disputes has grown over time and the number of family law disputes has diminished.125 These shifting tides suggest that the private usage of § 1782 is increasingly driven by corporations and increasingly involves the types of cases that are likely to result in voluminous discovery requests.126 Table 12 of Appendix C summarizes these findings.

4. Country of foreign proceeding.

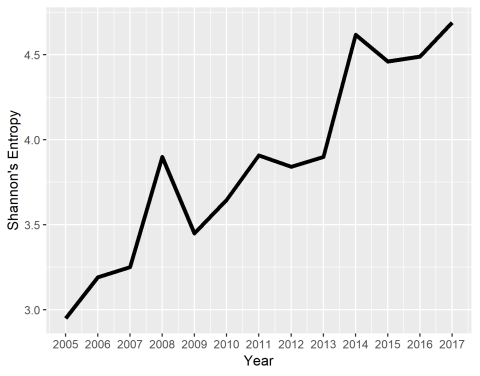

As the number of civil requests has increased over the years, so too has the diversity of countries from which they originate.127 This is true both for all requests taken together and for tribunal and party requests taken separately.

Breaking down the countries by region, legal system type, and Hague Evidence Convention status128 further illustrates the range of countries with which district courts are interacting. The majority of tribunal requests come from the Americas (approximately 62 percent), and the most significant region of growth during the study period is Eastern Europe. The majority of party requests come from Western Europe (approximately 61 percent), and the most significant region of growth for party requests is Asia.129 Tribunal requests predominantly seek discovery for use in civil law countries (approximately 93 percent) and in countries for which the Hague Evidence Convention is in force with respect to the United States (approximately 86 percent). Party requests are again more varied. About as many come from common law countries (approximately 44 percent) as civil law countries (approximately 46 percent), and a steady number comes from mixed or other legal systems (approximately 17 percent).130 Most party requests come from countries for which the Hague Evidence Convention is in force with respect to the United States (approximately 62 percent), but a significant number also come from other countries (approximately 43 percent).131 See Tables 1 and 2 below summarizing these findings.

| Requests from Foreign Tribunals | Requests from Foreign Parties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number 95% CI |

>Percentage 95% CI |

Number 95% CI |

Percentage 95% CI |

|

| Americas | 565483–660 | 62% 53%–73% |

273 219–343 |

23% 18%–29% |

| Caribbean | 0 0–11 |

0% 0%–1.2% |

60.7 40–96 |

5.1% 3.3%–8% |

| Western Europe |

166 126–222 |

18% 14%–24% |

732 639–837 |

61% 53%–70% |

| Eastern Europe |

112 81–158 |

12% 8.9%–17% |

53.9 35–87 |

4.5% 2.9%–7.2% |

| Middle East | 38.3 23–67 |

4.2% 2.5%–7.4% |

74.2 51–112 |

6.2% 4.2%–9.3% |

| Asia | 25.5 14–50 |

2.8% 1.5%–5.5% |

209 163–271 |

17% 14%–23% |

| Africa | 3.2 1–17 |

0.35% 0.11%–1.9% |

20.2 11–43 |

1.7% 0.92%–3.6% |

| Requests from Foreign Tribunals | Requests from Foreign Parties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number 95% CI |

Percentage 95% CI |

Number 95% CI |

Percentage 95% CI |

|

|

|

||||

| Common Law | 28.7 17–54 |

3.2% 1.9%–5.9% |

525 445–620 |

44% 37%–52% |

| Civil Law | 846 759–940 |

93% 83%–98% |

553 470–650 |

46% 39%–54% |

| Mixed/Other | 35.1 21–63 |

3.9% 2.3%–6.9% |

210 163–273 |

17% 14%–23% |

|

|

||||

| In Force | 779 >690–878 |

86% >76%–97% |

745 652–851 |

62% 54%–71% |

| Not in Force | 131 97–181 |

14% 11%–20% |

519 441–613 |

43% 37%–51% |

Breaking down the countries by rule-of-law rating,136 which was examined for the three-year period 2015–2017 due to limitations in the rule-of-law data used,137 more party requests are for use in countries with relatively high rule-of-law scores than are tribunal requests. Approximately half (57 percent) of party requests came from countries with rule-of-law scores in the top quartile compared to a third (33 percent) of tribunal requests. At the other end of the spectrum, approximately one-tenth (9.4 percent) of party requests came from countries with rule-of-law scores in the bottom quartile compared to approximately a quarter (24 percent) of tribunal requests. Note that a far greater proportion of party than tribunal requests (approximately 22 percent versus 0.95 percent) came from countries for which no rule-of-law rating is available, suggesting that more party requests are coming from countries that have not traditionally received as much attention in the US legal community. Table 3 below summarizes these findings.

These findings suggest that US courts are now interacting with a larger spectrum of legal systems worldwide, as opposed to the relatively narrow focus on the civil law systems within Western Europe and South America when the Hague Evidence Convention was negotiated during the 1960s.138 Since most legal scholarship on comparative law concentrates on these regions, it is unclear how conclusions from that literature extend to the rest of the world. There is a growing need to understand a more diverse set of legal systems worldwide, and the types of discovery to which they may be open.

| Requests from Foreign Tribunals | Requests from Foreign Parties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number 95% CI |

Percentage 95% CI |

Number 95% CI |

Percentage 95% CI |

|

| Quartile 4 | 101 >73–142 |

33% 24%–47% |

224 180–279 |

57% 46%–71% |

| Quartile 3 | 95.3 68–136 |

31% 22%–45% |

59.2 39–92 |

15% 9.9%–23% |

| Quartile 2 | 31.8 19–57 |

10% 6.3%–19% |

28 16–53 |

7.1% 4%–13% |

| Quartile 1 | 72.2 50–108 |

24% 16%–36% |

37.4 23–65 |

9.4% 5.8%–16% |

| No Rule-of-Law Score | 2.9 1–15 |

0.95% 0.33%–4.9% |

87.2 61–126 |

22% 15%–32% |

C. Outcome Analysis

Finally, I examined the outcome of requests. I used two crude proxies to gauge the complexity of requests: the number of docket entries and the number of orders.140 I also tracked whether the request was ultimately granted.141

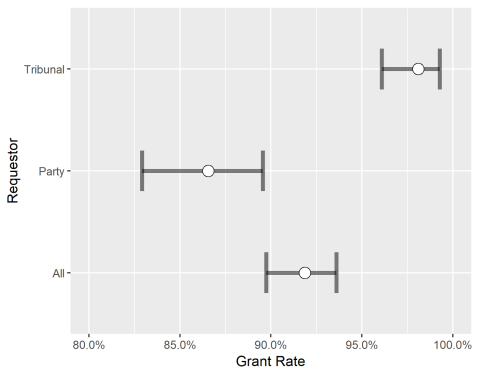

Foreign party requests are more complex and require more judicial activity to resolve than those from foreign tribunals. But both sets of requests are resolved relatively quickly and with minimal judicial activity. Requests from foreign tribunals are typically resolved with one order—the order granting or denying the request—and such requests were granted approximately 98.1 percent of the time.142 Requests from foreign parties typically take about three orders to resolve, and were granted approximately 86.6 percent of the time.143 The overall grant rate for all requests over the study period was approximately 91.9 percent.144 Excluded from these grant rate calculations are requests that did not reach resolution, often because the foreign proceeding had settled or otherwise reached a conclusion before the US discovery request reached completion, which in turn led the applicant to withdraw the request. Requests with no resolution outnumber denials in both tribunal and party requests, suggesting that the lack of timing coordination between the US discovery request and the foreign plenary proceeding limits the potential use of US discovery abroad.145 Figure 3 below visualizes the estimated grant rate for all requests, tribunal requests, and party requests over the study period. Tables 13, 14, and 15 in Appendix C summarize the numerical outcome data.

While it would be illuminating, it is not possible to compare these grant rates to those of domestic discovery requests. This is first and foremost because domestic discovery is typically negotiated between the parties at the outset and does not generate a record in the docket unless there is a disagreement and a motion to the court to resolve it. Additionally, I have not found any empirical research quantifying the rate at which motions to compel or motions for protective orders are granted domestically.

Figure 3: Estimated Grant Rates of Civil Requests

For 2015 only, I tracked the outcome and contestation status—meaning whether the request was challenged146 —for every request. Table 4 below summarizes the findings. Tribunal requests were granted 98.9 percent of the time and contested only 3.3 percent of the time. Party requests were granted 90 percent of the time and contested 37 percent of the time. The grant rate was higher for uncontested party requests (93.9 percent) than contested party requests (82.4 percent). The overall grant rate for both sets of requests was 94 percent and the overall contestation rate was 22 percent.

|

|

Requests from |

Requests from |

All Requests |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Overall Grant Rate148 |

98.9% |

90% |

94% |

|

Contestation Rate149 |

3.3% |

37% |

22% |

|

Grant Rate for |

67%150 |

82.4% |

81.1% |

|

Grant Rate for |

100% |

93.9% |

97.3% |

Logistic regression consistently indicated a strong negative correlation between a request being contested and its likelihood of being granted.151 This correlation was strongly indicated even in the presence of other variables significantly correlated with contestation.152 With respect to the remaining variables, logistic regression yielded inconsistent results.153

D. Unknowns

While docket analysis can shed light on the nature of foreign discovery requests and their outcomes in federal district courts, there are several critical pieces of information that docket analysis cannot reveal. First, it cannot show whether the foreign opposing party was notified about discovery requests coming from foreign parties. Requests are typically considered ex parte at the outset.154 If an ex parte request is granted, as most are, a subpoena and order are served on the discovery target, which is when the target learns of the discovery request. If the target is, or is related to, the foreign opposing party (itself difficult to ascertain in a systematic manner), then the latter learns of the request at the same time. If the target is not related to the foreign opposing party, notification cannot be systematically tracked because, as discussed in Part III, it is provided haphazardly and sometimes in the absence of a written record.155 Without knowing when notification was provided, I was unable to examine the extent to which the low contestation rate was due to lack of notice versus failure to contest. If the lack of notice is depressing the contestation rate, then it may also be raising the grant rate.

Second, for similar reasons, and also discussed in Part III, it was not possible to systematically track whether the foreign tribunal received notification of the request. Without this information, I was unable to differentiate lack of awareness that the discovery request had been made from lack of resistance to US discovery. Consequently, it was not possible to look for any overarching patterns in the types of foreign tribunals that are more receptive or opposed to US discovery.

Third, docket analysis provides incomplete information about when multiple discovery requests are made in the United States for the same foreign proceeding. Unlike domestic discovery requests that are a part of a larger plenary dispute and overseen by the same judge, each foreign discovery request is its own stand-alone action. Consequently, a single proceeding abroad can generate many discovery requests in different US district courts, each before a different judge. Sometimes, these requests are consolidated and other times they are not.

Finally, docket analysis does not provide systematic information about what happens after discovery is compelled—including whether the requested discovery was ultimately produced and submitted to the foreign tribunal, whether the foreign tribunal took it under consideration, and whether it affected the outcome of the foreign proceeding. In Intel, the Supreme Court asserted that district and foreign courts could, respectively, condition grants and acceptances of discovery on reciprocal exchanges of information between the foreign parties to maintain an appropriate measure of parity.156 District courts very rarely impose such a condition,157 and it is not possible to know from docket analysis if such a condition is imposed downstream by the foreign tribunal. In short, the impact of discovery compelled in the United States on foreign proceedings and foreign parties is largely unknown—to scholars relying on docket analysis as well as to US judges deciding foreign discovery requests, and, in most cases, granting them.158

III. Evaluating American Discovery in the World

Having characterized the rise in foreign demand for US discovery, the differences between demand from foreign tribunals and foreign parties, the high rates at which both types of requests are granted, and the key unknowns, this Part now evaluates doctrinally whether US judges are serving as effective discovery gatekeepers for foreign proceedings. All foreign discovery requests for use in civil disputes abroad are executed under § 1782, regardless of whether they began as a letters rogatory, a request under the Hague Evidence Convention, or a § 1782 application brought directly by a foreign party.159 Section 1782, in turn, has been described as a “screen” or “threshold determination” of whether to allow a foreign actor access to US discovery as it operates domestically.160 Once that threshold is overcome, § 1782 “drops out” and the “ordinary tools of discovery management” under the FRCP take over.161 It is assumed that the FRCP can be seamlessly translated from the domestic to the transnational context, and that district courts can weigh the interests of affected parties in foreign countries just as they do in the United States.

Drawing from the empirical findings above as well as district court proceedings and appellate court decisions, I argue that the machinery developed for domestic discovery is both improperly applied to—and ill-equipped to manage the challenges of—exported discovery. The blueprint for domestic discovery falls short in distinctive ways when applied to requests from foreign tribunals. In entertaining requests from foreign tribunals, federal courts have a greatly reduced justification for exercising the discretion they typically wield under the FRCP or under Intel’s discretionary factors. That is because tribunal requests are not adversarial, and there is no uncertainty surrounding whether the foreign tribunal is receptive to US discovery, given that the tribunal is making the request.

By contrast, requests from foreign parties are—and should be—adversarial between the two contending parties in the foreign dispute. But much of the time they are not, or they involve some but not all of the relevant stakeholders, resulting in a distorted adversarialism and missing information. I identify who the relevant stakeholders are and the information that each uniquely possesses, in the absence of which district courts are unable to undertake the analysis required under the FRCP or under Intel’s discretionary factors. Because judges are at a severe informational disadvantage when fielding requests from foreign parties, they have developed more manageable heuristics that place a heavy thumb on the scale for granting applications, which in turn threatens to undermine foreign litigation as well as universal and American litigation values.

Part III.A examines the underlying tenets of domestic discovery. Parts III.B and III.C look, respectively, at how foreign tribunal requests and foreign party requests deviate from this framework.

A. A Domestic Procedure for Foreign Use

At the core of American civil litigation is a litigant-driven system for obtaining information from adverse parties that aims to give both sides “the fullest possible knowledge of the issues and facts before trial.”162 That system is considered fundamental to fair adjudication because it narrows the issues, promotes settlement, and reduces surprises during trial.163 It relies on contending adversaries to negotiate a mutual exchange of information that reveals the strengths and weaknesses of each party’s case, and a judge to manage and resolve discovery disagreements. Although this vision of active judicial management of discovery has not been fully realized in the domestic context,164 setting out this ideal highlights the grave problems posed by discovery in the international context.

The FRCP give litigants broad authority to obtain from each other “discovery regarding any nonprivileged matter that is relevant to any party’s claim or defense.”165 This scope is subject to the requirement that discovery be “proportional to the needs of the case,” which requires a consideration of “the importance of the issues at stake in the action, the amount in controversy, the parties’ relative access to relevant information, the parties’ resources, the importance of the discovery in resolving the issues, and whether the burden or expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit.”166 The adversaries direct discovery requests to each other and negotiate the level of compliance.167 If they are unable to reach an agreement, a litigant can ask the court to compel discovery or for a protective order to forestall discovery.168

The current regime is the result of changes made over the past few decades in response to criticisms that discovery has been used abusively.169 The ongoing debate on the need for discovery reform in the United States is beyond the scope of this Article,170 except to note the measures courts have adopted to address discovery abuse. Most notably, the Supreme Court has reinterpreted the FRCP’s pleading standard, raising the bar for surviving a motion to dismiss as an indirect way to narrow discovery.171 The FRCP have also been revised to encourage “more aggressive judicial control and supervision,”172 both at the outset through pretrial scheduling conferences, and later on through the proportionality requirement. The adversaries and the court “have a collective responsibility to consider [ ] proportionality.”173 Participation from all parties is needed to elucidate the proportionality factors since each party holds different information, and that information may change or clarify over time.174 When parties disagree, the court’s role is to consider all the factors given the information provided by the parties, and to arrive at a case-specific determination, which is in turn reviewed for abuse of discretion.175 Some scholars have questioned whether judges can effectively apply the proportionality requirement, given the vagueness of the standard and judges’ relative lack of in-depth knowledge about the facts of the case.176 Some of the proportionality factors are difficult to quantify or require forecasting the value of sought-after information to the underlying dispute.177

The FRCP also allow parties to seek compelled discovery from nonparties178 —a process that maintains the core adversarial relationship between the parties by involving all parties to the dispute as well as the court presiding over the action. Notice and a copy of the subpoena must be served on each party to the dispute before it can be served on the nonparty target,179 so that other parties have an opportunity to object, to monitor the discovery, and to seek access to the information produced or make additional discovery requests of their own.180 When the nonparty is not subject to personal jurisdiction in the district where the case is pending, two district courts may be involved. The district court where the case is pending issues the subpoena,181 and the district court where the nonparty is found manages compliance and hears subpoena-related motions182 —a measure designed to protect nonparties through local resolution of disagreements. The judge in the compliance court is encouraged to consult with the judge in the issuing court on subpoena-related motions, since the latter is more familiar with the underlying case.183 Motions can also be transferred back to the issuing court so as not to disrupt the issuing court’s supervision over the underlying litigation, as might occur if the same discovery questions are likely to arise in many district courts or if the issuing court has already ruled on questions implicated by the motion.184 The FRCP recognize that the participation of the judge presiding over the case may be necessary due to her knowledge of the case and in order to consistently manage discovery requests across the case.

B. Use by Foreign Tribunals

When a district court receives a discovery request from a foreign tribunal, its role bears little resemblance to discovery within the United States. Under long-standing custom, these requests are typically considered on an ex parte basis.185 This practice is characterized by Professor Jim Pfander and Daniel Birk as an exercise of “non-contentious” Article III jurisdiction, which gives federal courts power to consider nonadversarial applications asserting a legal interest under federal law.186 While the target of a foreign tribunal request may oppose the discovery sought, leading to litigation that creates “a measure of adverseness,”187 tribunal requests are not adverse between the two contending parties in the underlying plenary dispute. For this reason, discovery requests from foreign tribunals have been likened to administrative subpoenas that federal courts enforce on behalf of agencies188 —a limited judicial role that has been described as “adjunct.”189

Without adversity between the two contending parties to the foreign dispute, district courts cannot exercise their usual broad discretion in evaluating domestic discovery disputes. There are no party needs or interests to weigh, and no disagreements over particular discovery requests to resolve. As noted in Part II, approximately 93 percent of foreign tribunal requests come from civil law countries,190 where discovery is primarily a judicial function.191

Nor is a district court entertaining a foreign tribunal request playing its usual screening role under § 1782. The statute requires that the requested discovery be “for use in a proceeding in a foreign or international tribunal.”192 Three out of the four discretionary factors enumerated by the Supreme Court in Intel—whether the discovery is available to the foreign tribunal without US court assistance, whether the foreign tribunal will be receptive to US court assistance, and whether the discovery request is an attempt to circumvent foreign discovery restrictions—weigh the likelihood that granting the request will offend a foreign tribunal.193 When the request is made by the foreign tribunal, it can be inferred that the discovery is for use in the proceeding it is adjudicating, and that the three comity-oriented Intel discretionary factors are met. Some courts acknowledge that these analyses collapse when the request comes from a foreign tribunal, while others parrot standard conclusory language that the Intel factors weigh in favor of granting the request.194

Not only are the bases for a district court’s usual exercise of jurisdiction under the FRCP and § 1782 inapposite, but for the approximately 86 percent of tribunal requests coming from countries for which the Hague Evidence Convention is in force with respect to the United States,195 district courts are further limited to a handful of permissible reasons for denying requests.196 This restriction under international law is not altered by the Convention’s internal execution through a preexisting general-use statute that is discretionary.197 For all of these reasons, the very low contestation rates and very high grant rates observed—typically with minimal judicial activity, the order granting the request being the only order issued by the court—are, for the most part, justified. These observations suggest that judges are highly deferential to the Hague Evidence Convention and, by extension, foreign tribunals, granting their requests more or less as a matter of course.198 Conversely, judges occasionally exceed their discretion by denying tribunal requests in violation of international law.199

C. Use by Foreign Parties

When a district court receives a discovery request directly from a foreign party, it bears some resemblance to discovery within the United States. The request is coming from a party to a foreign proceeding against an adverse party, which parallels the bipolar structure of domestic discovery disputes. Perhaps because of this analogous structure, some courts are confident that their “substantial experience controlling discovery abuse in domestic litigation” prepares them for “similarly root[ing] out sham applications under § 1782.”200 It is assumed that district courts are best positioned to weigh the needs and interests of parties affected by a foreign discovery request, just as they are in domestic discovery requests,201 and that the FRCP’s safeguards are well-suited to prevent foreign misuse.202 Consequently, the same abuse of discretion standard of review for ordinary discovery rulings is applied to § 1782 rulings.203

Yet, foreign discovery requests are distinctive in two key respects. First, there are two courts involved in a foreign discovery request—the US court entertaining the discovery request, and the foreign court presiding over the action. Since the plenary suit is necessarily abroad, it is governed by a different set of procedural rules. When a discovery request comes from a foreign party, it cannot be guaranteed that the foreign court or tribunal will accept US discovery under the FRCP as would another district court governed by the FRCP. Precisely for this reason, Intel set out three discretionary factors aimed at discerning whether the foreign court is receptive to exported discovery. Second, unlike domestic out-of-district discovery requests targeting a nonparty and involving two district courts, there is no clear requirement for informing or involving other parties to the foreign dispute or for consulting with the foreign court on subpoena-related motions. A foreign discovery request “stands separate from the main controversy” in a heightened way.204 There is both a heightened need for information given procedural differences between countries, and a reduced supply of information due to the absence of procedures for consulting the foreign opposing party and the foreign court. Consequently, requests from foreign parties cause more complications than those from foreign tribunals.

1. Missing stakeholders and information.

There is an acute lack of clarity as to who should be informed, involved, or consulted when a district court receives a discovery request from a foreign party. Following precedents concerning discovery requests from foreign tribunals, many courts have held that it is proper for § 1782 applications to be made on an ex parte basis even when that application comes from a foreign party.205 The rationale is usually that no prejudice will result because the target of the discovery will eventually have an opportunity to contest it once served with the subpoena.206 This reasoning does not distinguish between a discovery request that targets a party and one that targets a nonparty. It is the latter scenario that leaves the foreign adversary in the dark, preventing it from objecting to, monitoring, or seeking access to the requested discovery, as a domestic adversary would be able to do.207

Other courts have not condoned ex parte proceedings. But even when notification is required, courts do not agree on the legal basis for, or the components of, the requirement. Some have applied FRCP 45’s requirement that all parties be notified of discovery requests targeting nonparties.208 Others have applied local rules concerning ex parte orders—for instance, the Central District of California’s rule mandating a memorandum explaining why a matter was brought ex parte.209 Yet others have required notice as a matter of judicial discretion since § 1782 does not prescribe ex parte applications,210 or requested briefing on whether notice is needed.211 Some have even treated foreign discovery requests as if they are full cases or controversies, extending FRCP Rule 4’s requirement that a plaintiff serve a summons and a copy of the complaint on the defendant.212 The specific notification requirement has also varied: courts have ordered applicants to notify the target of the discovery request,213 the adverse party in the foreign proceeding against whom the evidence is to be used,214 and the foreign court itself.215 Sometimes notice is not required but given as a matter of courtesy, with or without a written record.

The confusion goes deeper: whether a foreign discovery request is a case or controversy is itself a question that has caused widespread discord across district courts, revealing uncertainty about the basic structure of these requests as well as the due process and personal jurisdiction requirements attending them.216 As noted in Part II, more than a hundred cases were recategorized by district courts either from a miscellaneous case to a civil case or vice versa during the study period of 2005 to 2017.217 Miscellaneous matters are typically ancillary or ex parte proceedings such as an out-of-district motion to compel or motion to quash, or the registration of a judgment from another district court.218 Civil matters are typically full cases or controversies between adversarial parties that invoke all the protections of the FRCP, including the requirement for a summons and service when a complaint is filed. That there is no case or controversy in the United States attached to foreign discovery requests has befuddled courts.

The result of this confusion and the accompanying erratic notification requirements are missing parties and stakeholders that ultimately deprive federal courts of the information they need to conduct rigorous analyses. Because foreign discovery requests are frequently decided without the knowledge and input of the foreign adversary or the foreign court, the range of basic information that judges struggle to ascertain is staggering. They include: whether the foreign proceeding is civil or criminal;219 whether the foreign proceeding is on appeal;220 whether the requested discovery is relevant to the foreign dispute;221 whether the foreign defendant has been served;222 the whereabouts of the foreign proceeding;223 the scope of discovery that is available in the country where the proceeding is being adjudicated;224 and whether a similar discovery request has already been denied in that country.225 The remainder of this Section examines how these missing stakeholders and this missing information impacts foreign litigation, basic notions of due process and fairness, and US litigation values.

2. Undermining foreign tribunals and litigation.

When the Supreme Court considered § 1782 in Intel, the Court stated that comity is “important as [a] touchstone[ ] for a district court’s exercise of discretion in particular cases.”226 The Supreme Court laid out four discretionary factors for district courts to consider, three of which are directed toward ensuring deference to and avoiding interference with foreign tribunals.227 The first factor is whether the foreign tribunal can itself order production of the evidence sought, or if it is unobtainable without US court assistance.228 Because the underlying discovery request in Intel sought evidence from a party to the foreign proceeding, the Supreme Court focused on the party status of the discovery target, writing that “when the person from whom discovery is sought is a participant in the foreign proceeding . . . , the need for § 1782(a) aid generally is not as apparent as it ordinarily is when evidence is sought from a nonparticipant in the matter arising abroad.”229 The second factor is whether US discovery assistance is desired abroad, and the Supreme Court instructed district courts that they may consider “the nature of the foreign tribunal, the character of the proceedings underway abroad, and the receptivity of the foreign government or the court or agency abroad to U.S. federal-court judicial assistance.”230 The third factor, related to the second, is whether the foreign discovery request “conceals an attempt to circumvent foreign proof-gathering restrictions.”231

Due to the lack of input from foreign tribunals and foreign opposing parties in § 1782 proceedings, and the open-ended nature of these factors,232 district courts have evolved simplified tests that lead to reflexive grants of foreign discovery requests. These simplified tests reflect Professor Maggie Gardner’s observation that the complex inquiries required in transnational cases encourage judges to develop analytical shortcuts that can lead to systemic bias favoring what is known (US parties and US law) over what is not known (foreign parties and foreign law).233 In the § 1782 context, the simplified tests systematically tip the scale toward granting foreign discovery requests while failing to properly apply Intel’s discretionary factors.

The first factor concerning whether the foreign tribunal can obtain the requested evidence without US assistance is often simplified to ask whether the target of the discovery request is a party or nonparty to the foreign proceeding. This analysis is easier to manage judicially, leading many courts to recite standard language that discovery is favored because it is sought from a nonparty.234 In fact, many discovery requests strategically target a token nonparty although the same evidence is also held by a party to the foreign proceeding. These token nonparties include American corporate affiliates of the foreign opposing party235 and American law firms that have represented foreign clients in US litigation.236 Most recently, the Second Circuit reversed a lower court’s grant of a § 1782 petition ordering Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP to turn over documents in aid of litigation in the Netherlands.237 The reversal was based not on fears of interfering with the foreign litigation but rather on concern that granting the request would undermine attorney-client communications in the United States as well as confidence in protective orders.238 In the absence of information from foreign courts, it is easier to locate a domestic rationale than a foreign one for limiting a doctrine whose primary effect is abroad.

Focusing on the nonparty status of the discovery target leads to a particularly absurd result when the discovery that is sought is in fact located abroad. While the drafters of § 1782 did not anticipate the statute to be used extraterritorially,239 some courts have compelled discovery from the very country where the foreign dispute is being adjudicated, because the FRCP reach documents and other tangible things “in the possession, custody, or control” of the discovery target.240 Such extraterritorial discovery is typically obtainable by the foreign court, and seeking it in the United States should raise strong suspicions of the applicant sidestepping foreign discovery restrictions.

The second and third factors concerning receptivity and whether a discovery request is an attempt to circumvent foreign proof-gathering restrictions are often considered in tandem and have resulted in a number of analytical shortcuts that effectively write these factors out of existence. The most prominent among them is burden shifting, since Intel did not specify burdens. Many district courts have held that the target resisting discovery must provide “authoritative proof” that the foreign court is not receptive.241 Authoritative proof of a negative is hard to come by, particularly where the discovery target is a US nonparty to the foreign litigation, who likely has no information about the foreign tribunal adjudicating the dispute abroad. Other analytical shortcuts that district courts have taken include: inferring that membership in the Hague Evidence Convention signals receptivity to US discovery242 despite the fact that nearly all Convention members have submitted a declaration objecting to pretrial discovery as such discovery is mandated by the FRCP;243 and relying on prior federal court decisions concluding that a foreign country is receptive without looking more deeply at how those courts arrived at their conclusion.244

The overarching result of these simplified tests is that district courts are reflexively granting foreign discovery requests because the comity-based discretionary factors are not gauging whether exported US discovery is assisting or interfering with foreign proceedings. Instead, appellate courts have instructed district courts that it is preferable to modify a request on the basis that it is too burdensome rather than deny or quash a request altogether.245 Information about the burden imposed by a discovery request is more readily available since it can be furnished by the local US target of the discovery, providing another example of how the absence of foreign courts and foreign parties in § 1782 proceedings results in domestic rationale driving a doctrine whose primary effect is abroad. If all else fails, courts reason that the foreign tribunal can simply disregard the discovery compelled by a US court,246 neglecting the judicial and private resources wasted, as well as the fact that foreign countries lacking broad discovery provisions typically do not have admissibility rules. That judges usually do not have any information about what happens to discovery after they compel it for foreign use amplifies this problem.

3. Undermining universal and American litigation values.