Testing for Multisided Platform Effects in Antitrust Market Definition

Introduction

Given myriad business practices and conditions, establishing certain antitrust harms requires context. This context often comes from framing the effects of the challenged conduct against the backdrop of some relevant market. In particular, a challenged practice’s anticompetitive impact may be outsized in a smaller market but insignificant in a larger one. For instance, the impact of a merger of two firms might be major if their combination captures 80 percent of a smaller market but relatively minor if that same combination represents only 10 percent of a larger market. In the latter, the combination is a drop in the bucket, while in the former it is a tidal wave. Plaintiffs thus have incentives to plead narrower relevant markets while defendants prefer broader ones. Yet this process of defining the relevant market can be highly technical, thrusting on judges the task of reining in increasingly complex economic and statistical analyses.

Challenging as this may be, the Supreme Court may face a taller task this term in Ohio v American Express Co.1 In particular, recent recognition of business methods known as “multisided platforms” further muddies the water by introducing additional complexity during market definition.2 These business methods connect two or more distinct groups of consumers that would benefit from interacting but face barriers to doing so. For example, payment-card platforms connect cardholders and merchants by issuing cards on one side of the platform and providing card-processing services on the other.3 Video game platforms connect gamers with developers by selling game consoles on one side of the platform and development kits and licenses on the other.4 Newspapers similarly connect subscribers and marketers by selling news content on one side of the platform and advertising space on the other.5 In this manner, selling more to one group influences demand by the other group.6 Often, the way platforms attract suitable participation is by offering discounts to the harder-to-attract group at the expense of the more ready-and-willing group. For instance, payment-card users frequently receive rewards—a sort of negative price—to ensure their participation.7 These are funded through fees assessed to merchants that desire cardholder business.8

To the technical process of market definition, multisided platforms thus add the challenge of determining whether the relevant market should incorporate all, some, or none of these interconnected groups. Because certain forms of antitrust analysis allow courts to trade off pro- and anticompetitive effects within the relevant market, defining that market serves to establish the space of permissible trade-offs.9 Notably, defining the relevant market to include all sides of the platform creates a broader space of allowable trade-offs than when the definition encompasses fewer sides. This is one reason that winning at market definition often means winning the case. Thus, it matters crucially whether and how courts incorporate “multisidedness” during market definition. This Comment suggests an approach to that inquiry.

Part I explores the challenges inherent in market definition. It situates this definitional process within the framework of the major antitrust enforcement laws to clarify the judicial requirements for defining a relevant market. It then frames market definition as both central and contested, pausing to chronicle Supreme Court jurisprudence designed to structure the inquiry and mitigate likely pitfalls. Part II explores the added challenge of whether the relevant market should incorporate all, some, or no sides of the platform. It describes the economic concept of a multisided platform and details the different ways that lower courts have addressed this challenge. Because plaintiffs and defendants often have opposing incentives concerning the number of sides that should be incorporated, knowing when to disregard or accept arguments concerning multisidedness is important. In this context, the courts could benefit from a test that seeks to determine when the relevant market should incorporate all sides of the platform. Hence, Part III proposes a two-stage test for multisidedness.

In the first stage, a court would ask (1) whether the business method can explicitly charge different prices to the distinct groups to which it provides goods or services; (2) whether each group’s benefit depends on the extent of participation by the other groups provisioned by the same business method and whether that participation varies based on market conditions; and (3) whether the platform is capable of, and generally does, set uniform prices in the markets in which each group participates. All three factors must hold, or multisidedness should be excluded from market definition.

Assuming all three stage one factors are satisfied, the court moves on to the second stage and asks whether the challenged conduct is designed principally to ensure the continued availability of the platform’s differentiated products. If so, the relevant market should encompass the market segments in which all sides of the platform operate.

I. Antitrust Market Definition

A market is a medium for the exchange of goods or services.10 For antitrust purposes, a relevant market is simply a market in which “a firm can raise prices above the competitive level without losing so many sales that the price increase would be unprofitable.”11 The judicial process of determining relevance is called “market definition.” It is important because antitrust plaintiffs must “prove harm . . . to the competitive process,”12 which often entails “a fact-intensive analysis of the challenged conduct . . . and its context.”13 Defining the extent of the relevant market provides that context.

For example, consider the Government’s monopolization claim in United States v E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co14 (“Cellophane”). At the time of the claim, du Pont’s raw output amounted to roughly 75 percent of the US market for cellophane.15 That same raw output, however, amounted to only 17.9 percent of the broader market for flexible packaging materials.16 The central issue, then, was whether the relevant product market was that for cellophane specifically or that for all flexible packaging materials. The Court held that the relevant market included all flexible packaging materials, and it considered du Pont’s 17.9 percent share of that larger market insufficient for a finding of monopolization.17 Apart from demonstrating that market definition is often outcome determinative, Cellophane also illustrates the concept of comparative harm. In particular, the anticompetitive impact of a challenged practice—here, du Pont’s cellophane share—may be outsized in a narrower market and insignificant in a broader one.

This Part explores the challenges inherent in market definition. Part I.A situates market definition within the statutory and judicial framework of the major antitrust enforcement laws. It clarifies the legal requirements for market definition and answers the question, “Why define the market?” Part I.B frames market definition as a contentious problem that is central to the outcome of an antitrust case. It also chronicles Supreme Court jurisprudence designed to guide and structure lower courts’ definition processes. Part I.C portrays market definition as problematic because of its economic and statistical complexity.

A. Background and Judicial Requirements for Market Definition

The Antitrust Division of the Department of Justice (DOJ), the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), state governments, and appropriately injured private plaintiffs may bring antitrust enforcement actions in federal court.18 The three core federal antitrust enforcement laws are the Sherman Act,19 the Clayton Act,20 and the Federal Trade Commission Act21 (FTC Act). Of these, §§ 1–2 of the Sherman Act and § 7 of the Clayton Act make up over 90 percent of the investigative workload of the DOJ’s Antitrust Division.22 As discussed in this Section, the requirement for market definition stems from judicial interpretation of these statutes.

Defining the relevant market typically involves establishing both the product market and the geographic market.23 The product market is the “part of a relevant market that applies to a firm’s particular product.”24 It is defined by “identifying all reasonable substitutes for the product and by determining whether these substitutes limit the firm’s ability to affect prices.”25 The geographic market is the “part of a relevant market that identifies the regions in which a firm might compete.”26 Together, the product and geographic markets provide the backdrop against which courts evaluate the impact of the challenged conduct.

The requirement for market definition in § 1 of the Sherman Act is judicial rather than statutory. The Act’s sweeping language simply bars “[e]very contract, combination in the form of trust or otherwise, or conspiracy, in restraint of trade or commerce among the several States.”27 Subsequent jurisprudence narrowed the Act’s broad language by holding that “Congress intended to outlaw only unreasonable restraints.”28 As such, an antitrust plaintiff must show (1) the existence of an agreement (2) that unreasonably restrains trade or commerce and (3) that implicates interstate or foreign commerce.29 Market definition is part of the second element—evaluating reasonableness typically requires the context of relevant product and geographic markets.30

In § 1 cases, courts evaluate unreasonable restraints using the aptly named “rule of reason”—a judicial doctrine based on the “totality of economic circumstances.”31 Circuit courts have established their own procedures for rule-of-reason analysis. For example, the Second Circuit uses a burden-shifting framework. Under this approach, a plaintiff bears the initial burden of “showing that the challenged action has had an actual adverse effect on competition as a whole in the relevant market.”32 Notably, this includes the requirement to sufficiently plead a relevant market.33 If the plaintiff meets its burden, responsibility shifts to the defendants to establish the “redeeming virtues” of their arrangement.34 Defendants often frame this evidence by defining a different version of the relevant market.35 The burden then shifts back to the plaintiff to show that these benefits could have been achieved through less restrictive alternatives.36

The requirement for market definition in § 2 of the Sherman Act is likewise judicial. Its statutory language simply targets monopolies. Specifically, § 2 criminalizes the conduct of those who would “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States.”37 As the Supreme Court explained in United States v Grinnell Corp:38

The offense of monopoly under § 2 of the Sherman Act has two elements: (1) the possession of monopoly power in the relevant market and (2) the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.39

The notion of the relevant market thus appears directly in the first element as the reference against which courts measure § 2 monopoly power.

The requirement for market definition in § 7 of the Clayton Act is also judicial. Congress enacted the statute in 1914 “because [it] concluded that the Sherman Act’s prohibition against mergers was not adequate.”40 The Clayton Act thus differs from the Sherman Act in proscribing “certain combinations of competitors” before they are able to produce “any actual injury, either to competitors or to competition.”41 The Supreme Court has reasoned that “Section 7 is designed to . . . arrest in their incipiency restraints or monopolies in a relevant market which, as a reasonable probability, appear at the time of suit likely to result from the acquisition by one corporation of all or any part of the stock of any other corporation.”42 In merger claims, then, market definition again provides context for the proposed combination’s likely impact.

B. Market Definition as a Problem of Context

Few question that market definition is central to antitrust law.43 Delineating the relevant market is among the first steps accomplished in any competition analysis and has been described as “one of the most important analytical tools for competition authorities.”44 Further, winning at market definition often means winning the case. As discussed above, comparing du Pont’s cellophane output to the market for all flexible packaging materials resulted in a 17.9 percent share, while comparing it to the market for cellophane revealed a 75 percent share.45 Because the Court looked to market share to inform the degree of anticompetitive impact,46 determining the basis for this comparison was largely outcome determinative.

Anything that determines the outcome is predictably contentious, so the Court’s market-definition jurisprudence reduces the scope of the definitional problem for the lower courts through two mechanisms. First, courts selectively apply the rule of reason discussed in Part I.A. Second, in rule-of-reason cases, courts apply rules that structure and focus the process of market definition.

As to the first, certain practices are “so plainly anticompetitive that no elaborate study of the industry is needed to establish their illegality.”47 Behaviors on this short, judge-made list per se violate § 1 of the Sherman Act. For instance, fixing prices across competitors within an industry is per se illegal.48 Colluding to rig bids for contract awards is another example.49 These behaviors invoke a bright-line rule that makes the context supplied by a relative market unnecessary: harm to competition “is presumed from the nature of the conduct.”50

Importantly, this means that the Court can control the scope of the definitional problem for Sherman Act § 1 offenses by deciding which conduct should require market definition in the first place. Challenges to behaviors classified as per se illegal avoid market definition while the Court subjects the remainder to market definition via the standard-like rule of reason.51 Additionally, its behavior-by-behavior approach allows the Court to adjust the per se list to account for changes in industry conditions or developments in analytical tools that permit a more finely tailored analysis.52

Second, the Court’s jurisprudence structures and focuses the definitional process for rule-of-reason cases under § 1 of the Sherman Act, as well as for Sherman Act § 2 and Clayton Act cases.53 The modern definition of the relevant product market hinges on substitutable—or functionally interchangeable—products. This stems from the Cellophane Court’s holding that “[d]etermination of the competitive market for commodities depends on how different from one another are the offered commodities in character or use, how far buyers will go to substitute one commodity for another.”54 The Court went on to explain:

The ultimate consideration . . . is whether the defendants control the price and competition in the market . . . they are charged with monopolizing. . . . [C]ontrol in the above sense of the relevant market depends upon the availability of alternative commodities for buyers: i.e., whether there is a cross-elasticity of demand between cellophane and the other wrappings. This interchangeability is largely gauged by the purchase of competing products for similar uses considering the price, characteristics and adaptability of the competing commodities.55

The Court found that price decreases for cellophane caused “a considerable number of customers of other flexible wrappings to switch” and thus broadly defined the relevant market to include all flexible packaging materials.56 In so doing, the Court enshrined cross-elasticity of demand as a definitional tool.

A few years after Cellophane, the Court reinforced its interchangeability approach when the Government, concerned about potentially anticompetitive effects,57 brought an action under the Clayton Act to enjoin the merger of two shoe retailers in Brown Shoe Co v United States.58 The Court expanded Cellophane’s approach, at the risk of creating further confusion, by explaining that within a “broad market, well-defined submarkets may exist which, in themselves, constitute product markets for antitrust purposes.”59 Instead of providing a bright-line rule to determine whether one is in a broad market or a submarket, the Court provided a nonexhaustive list of factors to consider: (1) industry or public recognition of the submarket as a separate economic entity, (2) the product’s peculiar characteristics and uses, (3) unique production facilities, (4) distinct customers, (5) distinct prices, (6) sensitivity to price changes, and (7) specialized vendors.60 By this light, it found the relevant lines of commerce were “men’s, women’s, and children’s shoes,” declining to recognize the appellant’s narrower “price/quality” distinctions.61

Shortly after Brown Shoe, the Court endorsed the consideration of relevant submarkets. In Grinnell, a seller of monitored burglary, fire, and flood alarm services argued against § 2 Sherman Act allegations by maintaining that the relevant market should be defined broadly to include any product that set off an audible alarm at the homeowner’s residence, even if that alarm was not centrally monitored in the way Grinnell’s was.62 The Court held that there is “no barrier to combining in a single market a number of different products or services where that combination reflects commercial realities.”63 That said, the Court considered substitutability, finding that Grinnell’s suggested combination of centrally and noncentrally monitored systems was too broad to reflect the commercial reality that some portions of the consumer population could not easily substitute between the two types of systems.64 The Court then affirmed the district court’s definition of the relevant market as that submarket of the alarm industry consisting of accredited central station services.65 Grinnell thus stands for the proposition that courts may fix the relevant market at the level of one or more submarkets, so long as the definition reflects commercial realities.

Several decades later, in Eastman Kodak Co v Image Technical Services, Inc,66 the Court issued an oft-cited holding that “[t]he proper market definition . . . can be determined only after a factual inquiry into the ‘commercial realities’ faced by consumers.”67 A group of independent equipment servicing firms brought an action under §§ 1–2 of the Sherman Act, alleging that Kodak’s policy of tying the sale of replacement parts to its sale of repair service undermined competing independent repair services. The Court considered the actual set of choices facing Kodak equipment owners—namely, from whom service and parts were available—in its assessment of commercial realities.68 Kodak, like Grinnell, stands for the proposition that a court may fix the relevant market at the level of one or more submarkets, so long as the definition reflects commercial realities.

Thus, the Court’s market-definition jurisprudence accomplishes two major things. First, it reduces the scope of the definitional problem by actively managing a list of per se illegal behaviors that do not require reference to a relevant market. Second, for behaviors not on this list, the Court structures and focuses the process of market definition by endorsing a cross-elasticity-of-demand approach premised on substitutability, by recognizing the possibility that relevant submarkets may exist, and by leaving the appropriate delineation to judicial factual inquiry into the commercial realities faced by consumers.

C. Market Definition as a Problem of Complexity

Despite the Court’s scope-limiting definitional jurisprudence, lower courts conducting “factual inquir[ies] into [ ] ‘commercial realities’”69 still must contend with the sheer complexity of defining a relevant market. Given their duty to oversee the definitional process, this pushes many judges outside their comfort zones. Two factors aggravate the problem. First, antitrust litigation depends heavily on complicated definitional tools and experts. Second, even seemingly straightforward concepts often have counterintuitive implications.

As to the first, because the relevant market is simultaneously complex, central to the outcome, and determined adversarially, it is unsurprising that reliance on experts has increased significantly in recent decades.70 Commentators attribute this dependence both to successes in the law-and-economics movement that have made case-by-case analysis more feasible and to advances in industrial organization—the economic field concerned with antitrust—that have rendered it “more mathematically rigorous and technically demanding.”71 Experts, in turn, rely on complex economic and statistical analyses to the point that they are now “standard fare in modern antitrust litigation.”72

While these developments permit a more tailored approach to evaluating the challenged conduct, they come at a cost. Judge Richard Posner observed that “[e]conometrics is such a difficult subject that it is unrealistic to expect the average judge or juror to be able to understand all the criticisms of an econometric study, no matter how skillful the econometrician is in explaining a study to a lay audience.”73 Further, perhaps the one thing more confounding than complexity is a variety of complexity. In summarizing the legislative history of the 1950 amendments to § 7 of the Clayton Act, the Brown Shoe Court concluded that Congress “provid[ed] no definite quantitative or qualitative tests by which enforcement agencies could gauge the effects of a given merger,” permitting instead a variety of methods.74 Market definition thus implicates a number of technical tools to implement Cellophane’s interchangeability approach.75

Second, as if variety of complexity were not enough, even seemingly straightforward concepts often have counterintuitive implications. Among these, the Cellophane fallacy is infamous. Recall that du Pont’s cellophane output amounted to roughly 75 percent of the US cellophane market but less than 18 percent of the flexible packaging materials market, and that the Court held that du Pont had not monopolized the relevant market, which it concluded was all flexible packaging materials.76 Unfortunately, the argument may be inconclusive. Imagine du Pont was a monopolist and had already raised prices accordingly. When prices are high, consumers may view some flexible packaging products as substitutes, not because they are functionally interchangeable, but because cellophane is simply too expensive. Including this type of substitution toward other flexible packaging materials could lead to an overbroad definition of the relevant market and the contradictory conclusion that du Pont was not a monopolist at all.77

This complexity has engendered two types of responses.78 Some have suggested that the tension between the limitations of generalist judges and their duty to preside over the intricacies of market definition might be neatly resolved by specialized antitrust courts. While such a change appears unlikely, empirical studies demonstrating higher rates of appeals for district-court judges with little antitrust training support this argument.79 Another approach has been the development of tools that do not rely on market definition.80 Although the DOJ and the FTC have embraced the approach as a conceptual supplement to market definition,81 current tools remain ill suited to the task of proceeding absent market definition, and courts have been loath to adopt them.82

* * *

All of this speaks to the idea that market definition is a judicially required, totality-of-the-circumstances process. It is adversarial rather than arbitrary, sophisticated rather than simple, and central rather than superfluous. In short, the outcome of the case often depends on how the lines are drawn—and these lines are battle lines.

While the process itself continues to evolve, so do industry conditions. Faced with new problems, firms have responded by devising new business methods or modifying old ones. But changed circumstances add an additional wrinkle to the definitional process. Increased recognition of the platform-based aspects of certain businesses has generated unanswered questions about whether and how the relevant market inquiry should account for them. This perceived gap forms the basis for Part II.

II. The Challenge Posed by Multisided Platforms

A platform is a business method employed by a firm to “enable interactions between [ ] groups of users, each of which cares about the size and attributes of the other group[s] on the same platform.”83 By extension, one can define a multisided platform as encompassing two or more such user groups. Although no two business methods are identical, the class exhibiting multisidedness merits special treatment. In particular, it raises “various novel and challenging empirical and analytical issues” during market definition.84

This Part explores the importance of multisidedness to market definition. Part II.A frames multisidedness as a developing concept that attempts to solve two problems—transaction costs and network externalities created by interconnected user groups—and Part II.B chronicles divergent judicial opinions on the topic. This state of affairs suggests the value of a test for multisidedness, which Part III develops.

A. Economic Concept of Multisidedness

Payment cards are a canonical example of a multisided platform.85 In this case, the platform is the payment architecture through which two groups—merchants and consumers—interact.86 On one side of the platform, rivals like Visa, MasterCard, American Express (“Amex”), and Discover compete to sell network services to merchants.87 That product involves authorization, settlement, and clearance of transactions.88 On the other side, Visa, MasterCard, Amex, and Discover compete to issue cards and provide services to card-holding consumers.89 This Section extends the payment-card example to consider three issues addressed by multisided platforms.

First, multisided platforms may be thought of as solving a problem of transaction costs—a broad term including marketplace bargaining, search, information, and enforcement costs. Before the advent of payment cards, merchants could engage in cash transactions or extend credit to individual consumers.90 Differences in shopping behavior make “transactions with some customers more profitable for the merchant than transactions with others.”91 Hence, for centuries, merchants have selectively extended open-book credit to consumers with “high time costs, high incomes, and high wealth positions” to foster repeat business.92 Additionally, when compared to cash, credit transactions prompt increased consumer willingness to pay, which translates into increased expenditures.93 Credit is thus desirable to merchants in the sense that its usage increases gross revenues. Consumers likewise benefit by avoiding the risk of carrying cash and the time costs involved with traveler’s checks.94 While mutually beneficial, extending credit on individual terms is costly. Merchants must invest in determining individual creditworthiness, writing terms, billing periodically, managing collection, and—importantly—absorbing the cost of capital.95 Conversely, consumers face a search problem in identifying merchants willing to extend credit. Payment platforms alleviate these transaction costs by facilitating credit and decreasing search costs.

Second, multisided platforms address the problem of interconnected demand. “Cardholders value credit or debit cards only to the extent that these are accepted by the merchants they patronize; affiliated merchants benefit from a widespread diffusion of cards among consumers.”96 Hence, merchant demand for network services and consumer demand for card issuance are linked by “indirect network effects,” which exist when a consumer’s willingness to pay depends on “the number of consumers . . . of another product.”97 Because neither side accounts for these effects, one can think of them as externalities.98 A major role of the multisided platform is to internalize these effects.

This internalization entails the cost of getting all necessary sides onboard and keeping sufficient proportions of each group in place.99 Amex reduced this onboarding cost by leveraging its preexisting customer base in the travel and entertainment industry, and before entering the payment-card market, Visa and MasterCard collaborated to pool merchants.100 Additionally, pricing strategy is critical to getting and keeping all sides onboard. Because one group may be harder to attract than another, platforms charge different prices to each user group. Difficult-to-attract groups may even receive below-cost pricing.101 This is the situation in the payment-card industry: some cardholders pay a reduced—or even negative—price by receiving rewards, while merchants pay positive prices.102 Thus, an essential function of a multisided platform is to manage this interconnected demand via tailored cross-subsidization.

Third, multisided platform analysis is new enough that the economic literature has yet to settle on definitive bounds for the concept. In other words, what precisely is meant by multisidedness is controversial. A recent survey identified over two hundred topical papers in print or working format that appeared between 2007 and 2015.103 Some commentators have advocated for broad interpretations, noting that “virtually all markets might be two-sided to some extent,” while simultaneously recognizing that such sidedness “is not always quantitatively important.”104 Yet this presents a challenge for courts engaged in market definition. Because the anticompetitive impact of a challenged practice may be outsized in a narrower market and insignificant in a broader one, plaintiffs may have incentives to plead narrower relevant markets while defendants prefer broader ones. In the presence of multisidedness, one would expect plaintiffs to contend that certain sides of the platform should be excluded from the definition of the relevant market. This was the case in United States v Visa U.S.A., Inc,105 which involved a § 1 Sherman Act claim. The Government contended that the relevant market should exclude the market in which the card-issuing side of the platform operated, focusing instead on the market in which Visa provided network services to merchants.106 One might then expect a defendant facing this definition to counter by including both the market for network services and the market for card issuance in its proposed definition.107 Thus, the problem of market definition is exacerbated when the notion of multisidedness itself is subject to uncertainty. In that case, plaintiffs could not only argue for narrower definitions of the relevant market, but they could also argue for more restrictive interpretations of the concept of multisidedness itself. As Part II.B discusses, these challenges have led to a series of nebulous lower-court opinions.

B. Nebulous Opinions on Multisided Platforms

Judicial treatment of multisidedness during market definition is nascent, and courts have predictably differed in how to navigate the topic. This Section uses Sherman Act § 1 cases as a vehicle for exploring their differences. Specifically, the differences reflect alternate approaches to implementing § 1’s rule of reason in the presence of multisidedness.

As discussed in Part I.A, rule-of-reason analysis under § 1 of the Sherman Act implicates market definition.108 Conditional on a well-defined market, the rule of reason may be thought of as a balancing test: determining whether a restraint is unreasonable is akin to asking “whether its anticompetitive effects outweigh its procompetitive effects.”109 Because courts may trade off pro- and anticompetitive effects within the relevant market,110 defining the relevant market is tantamount to establishing the space of allowable trade-offs. In particular, defining the relevant market to include all sides of the platform creates a broader space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs: it provides the opportunity to trade procompetitive effects on one side of the platform for anticompetitive effects on the other side.

This environment creates high stakes that run throughout a growing body of case law. By considering cases that address the issue either directly or indirectly, this Section examines the ways in which lower courts have wrestled with whether and how to incorporate the transaction-cost and interconnected-demand features of multisidedness during market definition. The approaches may be grouped into those that have minimized the impact of multisidedness on market definition, those that have hedged on the issue, and those that have considered evidence of multisidedness directly.

1. Some courts have minimized multisidedness’s impact on market definition.

Cases that define the relevant market as encompassing fewer than all sides of the platform narrow the space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs and effectively eliminate a defendant’s arguments that it manages interconnected demand. These may include actions taken to onboard various constituencies as well as the provision of benefits, such as differential pricing, needed to keep them on the platform.111 The Second Circuit took this approach in Visa, which involved a Sherman Act § 1 claim.112 The Government challenged exclusivity rules put in place by Visa and MasterCard that prohibited their member banks from issuing Amex and Discover cards,113 meaning that bank customers would have to look elsewhere for these products. In applying Cellophane’s interchangeability test, the court concluded that network services lacked reasonable substitutes, and it likewise determined that cash, checks, debit cards, and proprietary cards did not reasonably substitute for card issuance.114 Although Grinnell said there is “no barrier to combining in a single market a number of different products or services where that combination reflects commercial realities,”115 the Second Circuit found that the case involved “two interrelated, but separate, product markets.”116 The court then evaluated the challenged conduct’s effect on competition in the network services market without reference to procompetitive benefits from the issuance side of the platform.117

The Second Circuit likewise restricted the space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs in United States v Apple, Inc.118 The case involved price fixing between Apple and e-book publishers in response to Amazon’s low Kindle pricing.119 Although the court held that the organizer of a “price-fixing conspiracy” across competitors may not escape a finding of per se illegality under § 1 of the Sherman Act,120 it also conducted an abbreviated rule-of-reason analysis in the alternative.121 While e-book platforms may exhibit multisidedness—with publishers on one side122 and customers desiring access to a large variety of works on the other—the court did not include both sides of the platform in its eventual definition. Instead, its relevant market included competition only between rivals like Amazon and Apple for publisher contracts.123 This had the effect of limiting allowable pro- and anticompetitive effects to those on the publisher side of the platform. Accordingly, the court rejected Apple’s arguments that its entry “represented an important procompetitive benefit of the horizontal price-fixing conspiracy it orchestrated.”124

Cases like Visa and Apple, which define the relevant market as encompassing fewer than all sides of a platform, restrict the space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs and render a defendant’s management of interconnected demand irrelevant. This is often fatal to the defendant’s case. That said, even when multisidedness legitimately exists, excluding it is not necessarily inappropriate. This observation forms the basis for Part III.

2. Some circuits have hedged with respect to interconnected market segments.

Not all courts have treated multisidedness directly. However, knowing whether a court permits trade-offs across related market segments—a more basic inquiry—may be indicative of how it would view multisidedness.125 The Third Circuit, in King Drug Co of Florence, Inc v SmithKline Beecham Corp,126 did not address multisidedness directly and hedged on whether it would allow trade-offs across markets. The case involved an agreement challenged under § 1 of the Sherman Act,127 in which the defendant—a manufacturer of chewable epilepsy and bipolar disorder pharmaceuticals—agreed to relinquish its right to produce an authorized generic for a certain period of time.128 In particular, the court allowed that “at the pleading stage plaintiffs have sufficiently alleged that any procompetitive aspects of the chewables arrangement were outweighed by the anticompetitive harm,” but then mused that “[i]t may also be (though we do not decide) that ‘procompetitive effects in one market cannot justify anticompetitive effects in a separate market.’”129 The ability to operate across distinct markets characterizes a multisided platform.130 Therefore, the Third Circuit’s reservation of judgment makes it hard to predict whether it will eventually incorporate multisidedness into market definition.

The Ninth Circuit is likewise undecided whether pro- and anticompetitive effects may be traded off across market segments. It wrestled with the issue in Paladin Associates, Inc v Montana Power Co.131 In that case, a private plaintiff brought a § 1 Sherman Act case dealing with the assignment of natural gas transportation rights. While the court had considered a market for pipeline transportation, the defendants’ customers testified that the assignments had a procompetitive effect in the natural gas commodity market. Acknowledging the effect, the court stated, “It may be, however, that this procompetitive effect should not be considered in our rule of reason analysis, based on the theory that procompetitive effects in a separate market cannot justify anti-competitive effects in the market . . . under analysis.”132

3. Other courts have considered evidence of multisidedness.

Some courts have made implicit or explicit usage of multisidedness in arriving at their holdings. If multisided platforms solve a transaction-cost problem between groups that have trouble interacting absent the platform,133 then a significant challenge managed by payment platforms is facilitating credit extension and payment among the thousands of different banks used by merchants and cardholders. National Bancard Corp v Visa U.S.A., Inc134 (“NaBanco”) involved a privately enforced claim under § 1 of the Sherman Act in which NaBanco alleged that Visa addressed this problem anticompetitively.135

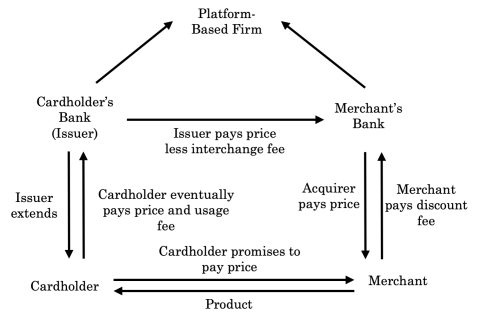

Understanding the claim requires a bird’s-eye view of the platform’s mechanism, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Five-Party Payment System

When a cardholder makes a credit purchase using Visa or MasterCard, the merchant’s bank pays the merchant the full purchase price and collects a discount fee from the merchant for performing the service.136 Before doing so, the cardholder’s bank typically extends credit to the cardholder and arranges to pay the merchant’s bank the purchase price less an interchange fee.137 This system solves the transaction-cost problem that would arise if the merchant’s bank had to bilaterally contract with each and every cardholder’s bank.138 A platform like Visa or MasterCard sets the interchange fee directly, which, in turn, helps determine the amount of the merchant’s discount fee.

NaBanco claimed that Visa’s practice of centrally setting the interchange fee was tantamount to price fixing across competitors within an industry.139 If supported by the facts, such price fixing would be per se illegal under § 1 of the Sherman Act.140 The NaBanco decision is unique in that it considers evidence of multisidedness, not just to constrain the space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs, but also to establish the need for rule-of-reason analysis (and market definition) over § 1’s per se rule. The Eleventh Circuit held that the challenged conduct “was not a naked restraint of competition and therefore not per se price fixing.”141 In arriving at this conclusion, it considered the value of the platform as a “joint enterprise,” recognizing its need to manage the problem of getting and keeping both cardholders and merchants onboard.142 It reasoned that the interchange fee “accompanies ‘the coordination of other productive or distributive efforts of the parties’ that is ‘capable of increasing the integration’s efficiency and no broader than required for that purpose.’”143

Evidence of multisidedness was also instrumental to the Second Circuit’s market definition in United States v American Express Co144 (“Amex”). The case involved a § 1 Sherman Act allegation and a payment-card platform similar to the one at issue in Visa.145 In particular, Amex, Visa, and MasterCard put various provisions—including Amex’s nondiscriminatory provisions (NDPs)—into their contracts with card-accepting merchants, prohibiting them from steering cardholders toward other methods of payment.146 Plaintiffs alleged that absent the NDPs, “merchants would be able to use steering ‘at the point of sale to foster competition on price and terms among sellers of network services’ by encouraging customers to use less expensive or otherwise preferred cards.”147 Visa and MasterCard settled; Amex went to trial. In contrast to its market definition in Visa, the Second Circuit in Amex held that the district court had erred in declining to “collaps[e] the issuance and network services markets into a single platform-wide market for transactions.”148 In applying Cellophane’s interchangeability standard and Grinnell’s commercial-realities framework,149 the court distinguished Visa by explaining:

The Visa panel thus did not conduct a rule-of-reason analysis to determine whether vertical restraints were inhibiting competition on one particular side of a two-sided platform. Instead, the Visa panel conducted a rule-of-reason analysis to determine whether horizontal restraints were inhibiting competition on one particular level of competition contained within a two-sided platform.150

Conditional on this logic, the relevant product market in Amex was the entire multisided platform, which the court established in part by reference to intraplatform feedback effects between merchants and cardholders. In particular, payment-card platforms must price so as to bring and keep both sides onboard.151

While the outcome appears correct,152 were Visa to write similar exclusionary contracts today, the court’s horizontal–vertical distinction may be insufficient to produce the same outcome. Understanding why requires understanding horizontal and vertical restraints. A horizontal restraint is one “imposed by agreement between competitors at the same level of distribution. The restraint is horizontal not because it has horizontal effects, but because it is the product of a horizontal agreement.”153 A vertical restraint is one “imposed by agreement between firms at different levels of distribution.”154

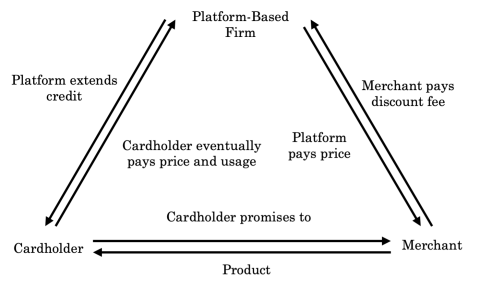

The NDPs in Amex are best viewed as vertical restraints with intended effects on horizontal competition. First, Amex operates a three-party system, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Three-Party Payment System

Such a system differs from that of Visa and MasterCard (shown in Figure 1) in that it eliminates the banking layer.155 Second, the Amex NDPs appeared in a contract between Amex and its merchants.156 Such restraints are vertical.157 They prevented merchants from steering cardholders on the other side of the platform toward other methods of payment, including those offered by competing platforms.158 These intended effects are thus horizontal.

On Visa’s facts, its exclusionary rules were likely horizontal restraints. This is because Visa and MasterCard were structured as “open, joint venture associations with members (primarily banks) that issue payment cards, acquire merchants who accept payment cards, or both.”159 The district court found that the members competed with each other on “pricing, fees and finance charges, product features and other services for cardholders and merchants.”160 As such, the Second Circuit found that the restrictive provision was “a horizontal restraint adopted by 20,000 competitors.”161 In terms of Figure 1, the court determined that the restraint existed between banks at the issuer–acquirer level and treated the platform as a mere extension of those banks. The Amex court then distinguished the cases on this horizontal–vertical logic.162

However, MasterCard went public in 2006, and Visa followed suit in 2008.163 Doing away with the membership-based structure increases the likelihood that similarly situated contracts between Visa and the issuing banks could be characterized as vertical restraints. In part, this is because the absence of shareholders had supported Visa and MasterCard’s characterization as joint ventures.164 In terms of Figure 1, the change in corporate structure may compel future courts to treat the platform as a stand-alone entity and determine that similarly situated contracts exist between the platform firm and an issuing bank, rather than among banks at the same level.165 Because such contracts would nevertheless impact industry competitors, they would be properly considered vertical agreements intended to have horizontal effects on competition. However, Amex’s NDPs were likewise vertical restraints with intended horizontal effect. The structural change thus tends to erode the Second Circuit’s horizontal–vertical distinction.

This erosion is consequential in the following ways. First, because Visa and Amex were distinguishable on the court’s horizontal–vertical logic at the time of decision, the test in Part III is not strictly required to reconcile the two cases. However, it serves as an alternative approach to distinguishing the cases without recourse to horizontal–vertical logic. In the present environment, such an approach could be useful in cases in which directionality is harder to tease out or fails entirely. Second, advances in economic and statistical methodology have rendered finer-grained analysis more feasible.166 To the extent that horizontal and vertical labeling stands in as a first-order approximation of the more nuanced fundamentals of competition in the relevant market, and to the extent business methods continue to evolve in complex—and potentially nondirectional or multidirectional ways—improvements in methodology may render such labeling less important. When horizontal and vertical distinctions tell an incomplete tale, the test in Part III permits analysis without recourse to directionality.

III. Testing for Multisidedness during Market Definition

This Comment presents market definition as a contested problem of comparative harm and complexity. Because rule-of-reason analysis allows courts to trade off pro- and anticompetitive effects within the relevant market,167 defining the relevant market is akin to establishing the space of allowable trade-offs.168 This is why market definition is frequently outcome determinative. To this, multisidedness adds the challenges of incorporating transaction costs and interconnected demand. Predictably, courts have differed on how to navigate these waters. In particular, defining the relevant market to include all sides of the platform creates a broader space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs during rule-of-reason analysis. Because plaintiffs and defendants often have opposing incentives concerning the applicability of multisidedness to market definition,169 knowing when to disregard or accept arguments concerning multisidedness is crucial. In this context, the courts could benefit from a test that seeks to determine when the relevant market should incorporate all sides of the platform.

Part III.A proposes a two-stage test. In the first stage, a court should exclude proffered multisidedness when any of the listed factors do not hold. In the second stage—and conditional on passing the first—a court should, under particular conditions, define the relevant market to include all sides of the platform. Part III.B applies this test to demonstrate an alternate approach to distinguishing the Second Circuit’s decisions in Visa and Amex.

A. Testing for Multisided Effects

Although recent, multisided platform theory is nevertheless well studied.170 Various parts of the economics literature have proposed guidelines for courts, including lists of factors for the courts to consider when dealing with multisided platforms.171 This Comment likewise proposes a list; however, its contribution is to compile factors—justified both by case law and economic theory—that serve as a test for when courts should and should not incorporate multisidedness in market definition.

There are at least four reasons for developing such a test. First, courts justifiably can and do consider evidence of multisidedness in market definition.172 Second, market definition will likely persist in the foreseeable future. While academics and practitioners have developed measures of anticompetitive behavior that do not rely on market definition, Supreme Court precedent continues to endorse analysis of the relevant market for many types of claims.173 Third, avoiding unjustified inclusion of multisided effects in market definition promotes judicial accuracy. Fourth, clarity serves to decrease meritless and costly market definition. In this sense, an overly inclusive interpretation risks a slippery slope in which antitrust enforcement lacks teeth against broadening relevant markets. Likewise, an excessively restrictive interpretation may benefit parties that are not typically the objects of antitrust law.174

The test proceeds in two stages. In the first, a court asks (1) whether the business method can explicitly charge different prices to the distinct groups to which it provides goods or services; (2) whether each group’s benefit depends on the extent of participation by the other groups provisioned by the same business method and whether that participation varies based on market conditions; and (3) whether the platform is capable of, and generally does, set uniform prices in the markets in which each group participates. All three factors must hold, or multisidedness should be excluded from market definition.

Assuming all three stage one factors are satisfied, the court moves on to the second stage and asks whether the challenged conduct is designed principally to ensure continued availability of the platform’s differentiated products. If so, the relevant market should encompass the market segments in which all sides of the platform operate.175

1. Stage one: exclusion.

The first stage aims to exclude proffered multisidedness that does not satisfy certain conditions. The same task might be accomplished by a clean definition of multisidedness—and in many ways the first stage is a sort of “definition.” However, it is important to distinguish between definitions meant to frame multisidedness conceptually and those suited for use in scoping the relevant market. Because conceptual definitions must introduce readers to a potentially unfamiliar topic, they involve some level of curation. For example, consider two popular definitions. Professors Jean-Charles Rochet and Jean Tirole propose a price-centric interpretation of multisidedness176 while Professors David Evans and Richard Schmalensee propose an interpretation centered on transaction costs and interconnected groups.177 Although they differ in focus, these definitions are not contradictory. And courts appear to cite them for their conceptual-framing value rather than during market definition itself.178

Any operational definition of multisidedness intended to help scope the relevant market must be capable of both fine-grained and flexible application to ex ante fact patterns. This is because the Kodak Court mandated a fact-intensive inquiry into consumer-level commercial realities,179 meaning that rule-of-reason analyses should consider potentially unique business practices, industry structures, and consumer interactions. Further, in Times-Picayune Publishing Co v United States180 and Grinnell, the Court endorsed the consideration of interconnected markets and submarkets, both of which are germane to multisidedness.181 The factors of an operational definition implicating interconnected markets must be foundational enough to satisfy the fine-grained flexibility mandate of Kodak, Times-Picayune, and Grinnell.

Stage one of the test is just such an operational definition. This Comment argues that the factors best suited to fine-grained and flexible analysis are the primitives from which applied theorists build industrial organization models of multisidedness.182 In this context, the term “primitives” refers both to the motivating problems a multisided platform must solve and the necessary elements of businesses that try to address those problems. The former pertains to notions of transaction costs and interconnected demand that motivated economists to develop multisided platform theory in the first place.183 Any test for multisidedness must incorporate these motivating problems or risk answering the wrong question entirely.

These primitives are appropriate for constructing a legally justified test for four reasons. First, antitrust law is inseparable from its economic underpinnings, and the courts have long looked to the industrial organization literature to inform judicial precedent.184 Second, the fact that these primitives are capable of generating models with distinct predictions about industry behavior suggests they are also elemental enough to satisfy Kodak’s flexibility mandate. Third, although it may be appropriate for conceptual definitions of multisidedness to differ in focus, greater commonality may be found in the primitives.185 Finally, were courts to adopt particular conceptual definitions, they could become precedential. At best, because any definition necessarily implicates a particular focus, adopting one definition would constrain a court in cases in which separate fact patterns suggest an alternate focus. At worst, such a limitation runs counter to Kodak’s rule-of-reason principles. In this vein, this Comment treats these conceptual definitions of multisidedness as helpful signposts in a movement toward the primitives.

- Factor one: whether the business method can explicitly charge different prices to the distinct groups to which it provides goods or services.186 A court should consider evidence of whether the proffered platform provisions distinct groups on distinct sides of the platform as well as whether it can charge those groups differentially. This is significant as an exclusionary criterion. First, consider a video game platform that connects gamers with developers by selling game consoles on one side of the platform and development kits and licenses on the other.187 Gamers and developers constitute distinct groups, and the platform’s function is to facilitate their interaction. While both groups purchase products from the platform (consoles and development licenses), the transaction as a whole may also be thought of as having a demand-side component (gamers) and a supply-side component (developers). The sides purchase distinct products and thus may be explicitly charged different prices. Newspapers similarly connect subscribers and marketers by selling news content on one side of the platform and advertising space on the other.188 This transaction, too, may be thought of as having a demand side and a supply side (advertisers that desire viewer impressions and readers who tolerate the ads in order to access content). The ability to recharacterize the transaction as one of demand and supply sides, however, is not essential. Consider an online dating platform that seeks to pair women and men.189 The groups may, though need not be, charged different prices. Second, it helps to see an example of groups that are not distinct. Take the example of a firm that sells a chat application without advertising. Its goal is simply to maximize profits without regard to any particular composition of the usership. While the users may happen to be quite diverse, this is beside the point. The firm’s business method does not center on facilitating interactions in which the defining feature is that the users belong to meaningfully separate groups.

- Factor two: whether each group’s benefit depends on the extent of participation by the other groups provisioned by the same business method and whether that participation varies based on market conditions.190 A court should consider evidence of cross-network effects that increase each group’s benefits as participation by the other groups increases.191 This factor is significant as an exclusionary criterion. First, it rejects multisidedness for a firm in the absence of cross-group network effects. For example, cardholders benefit from widespread acceptance by merchants, and merchants value widespread diffusion of cards among consumers.192 Developers value game consoles that have more gamers, and gamers value consoles with more games.193 Of note, the presence of within-group network effects alone is insufficient to justify multisidedness absent the presence of cross-group network effects. For example, if users’ benefits of participating in a chat application increase uniquely as a function of the number of other users of the same type, then a within-group network effect exists. This factor does not bar the presence of such effects; it merely requires the presence of cross-network effects. As discussed, payment-card platforms display cross-network effects between cardholders and merchants,194 but if merchants also happened to benefit more when more merchants used the platform, this would be a permissible—but unnecessary—within-group effect.195 Second, this factor rejects multisidedness when the extent of user participation on both sides does not vary with market conditions. Such invariance is a poor fit for a notion of multisidedness that requires user groups to adjust to price changes and changes in the extent of other groups’ participation.196 Third, this factor rejects multisidedness for a multiproduct firm when the argument for multisidedness is based solely on product complementarity. For example, the buyer of complementary products, such as a phone and a drop-resistant case, internalizes the costs and benefits of each in deciding to purchase both.197 This does not occur for multisided platforms, in which distinct user groups fail to internalize cross-network externalities absent the platform. Fourth, this factor rejects multisidedness when user groups can reach an efficient outcome through bargaining. In other words, Professor Ronald Coase’s theorem198 must give way as a necessary condition to multisidedness.199 This simply recognizes the fact that a multisided platform solves a transaction-cost problem or risks answering the wrong question.200

- Factor three: whether the platform is capable of, and generally does, set uniform prices in the markets in which each group participates.201 A court should consider evidence of whether the platform has market power and reject multisidedness for a firm lacking at least some degree of market power on each side of the platform. Absent this ability to influence prices on each side, the firm is a mere price taker: it lacks the power to adjust and coordinate the interrelated prices needed to get and keep all sides onboard.202 In this situation, the firm is better modeled as a distributor.203 Two points are germane. First, this factor focuses on whether the firm possesses the minimal degree of market power needed to coordinate across-group prices. For the court, this is a narrower inquiry than quantifying the anticompetitive implications of the improper acquisition of or abuse of market power, which is a broader purpose of antitrust law.204 Second, this factor does not require a firm to set perfectly uniform prices on each side of the platform. While models of market power generally assume the infeasibility of within-group price discrimination, such a practice need not stand as an absolute bar to the consideration of multisidedness.205

2. Stage two: inclusion.

Should any of the stage one factors fail to hold, multisidedness should be excluded from market definition. However, conditional on the presence of all first-stage factors, a court should ask whether the challenged conduct is designed principally to ensure continued availability of the platform’s differentiated products.206 If so, the relevant market should encompass the market segments in which all sides of the platform operate.

This factor serves as an inclusionary criterion to recognize conduct necessary to preserving the benefits of the platform. First, multisidedness is important during market definition when the challenged conduct prevents distinct user groups from free riding—that is, obtaining platform benefits without paying for them. This is often possible when the platform has difficulty monitoring each user group’s compliance with its terms, either because doing so is costly or impractical. For example, say a job-matching service provided résumé review services to employers and advocacy services to prospective employees. Benefits from the platform’s solution to their matching problem in hand, widespread ability of the user groups to avoid compensating the platform would represent a threat to continued availability of the platform’s products.207 The platform might avoid the problem by charging employers an up-front membership fee calibrated to represent the return it would have earned had it elected to bill firms after successfully delivering matches.

Second, this factor accepts multisidedness when the challenged conduct prevents arbitrage.208 The ability of any user group to resell the platform’s product in a secondary market would undermine the platform’s ability to coordinate prices across user groups, threatening its continued existence. For example, if a gaming platform operated a price strategy that sold consoles to gamers for relatively inexpensive prices and those users were able to turn around and resell their discounted consoles at higher prices to developers across the platform (say, if developers also required consoles but had to pay more for them), then this would undermine the platform’s ability to coordinate prices. Likewise, if gamers were able to purchase unlicensed imitation games, then developers would have little incentive to participate in the platform.

B. Application of the Multisidedness Test to Distinguish Visa and Amex

Although Visa and Amex both involved payment-card systems, the Second Circuit determined that network services and card issuance were “two interrelated, but separate, product markets” in Visa209 but held that the district court erred by failing to “collaps[e] the issuance and network services markets into a single platform-wide market for transactions” in Amex.210 Part II.B.3 made the point that distinguishing cases on horizontal–vertical logic poses certain challenges.211 This Section explores the two cases through the lens of Part III.A’s proposed multisidedness test.

Applying the first stage to Visa and Amex fails to exclude multisidedness from consideration during market definition in either case. The first factor asks whether the business method can explicitly charge different prices to the distinct groups to which it provides goods or services. The business methods in the two cases targeted both cardholders and merchants, which are distinct user groups. While not strictly required, the payment systems supplied distinct products to each group: merchants required the authorization, settlement, and clearance of transactions inherent in the network services product, while cardholders required issuance. Importantly, merchants paid a positive price in the form of a discount fee while consumers paid a reduced—or even negative—price by receiving rewards. Thus the first factor does not exclude multisidedness.

The second factor asks whether each group’s benefit depends on the extent of participation by the other groups provisioned by the same business method and whether that participation varies based on market conditions. Cardholders benefited from increased acceptance by the merchants they patronized, and merchants benefited from increased card diffusion among patrons, which means that cross-group network effects were present.212 One would expect that participation varied based on prices and other market conditions (for example, the extent of the rewards offered), and the presence of transaction costs precluded side bargains.213 Thus the second factor does not exclude multisidedness.

The third factor asks whether the platform is capable of, and generally does, set uniform prices in the markets in which each group participates. As evidenced by their ability to set the interchange fee, which had implications for both the merchant discount fee and consumer-card price structure, the firms possessed sufficient market power to set prices for each user group and thus to coordinate prices across both sides. Therefore, the third factor does not exclude multisidedness.

Because all first-stage factors hold, the court would proceed to the second stage and ask whether the challenged conduct was designed principally to ensure continued availability of the platform’s differentiated products. Recall that in Amex, the challenged conduct involved antisteering provisions put in place by Amex, Visa, and MasterCard, which prevented merchants from steering cardholders toward other methods of payment.214 Steering is lucrative from the merchant’s perspective because it enables the merchant to minimize the merchant discount fees associated with consumer card usage.215 In particular, the antisteering provisions prohibited merchants from providing Amex’s cardholders with point-of-sale incentives to use another method of payment.216 One can say that widespread steering would have posed a threat to the continued availability of Amex’s differentiated products. As explained below, this is because the value of Visa and MasterCard as differentiated products comes primarily from their position as counterpoints to Amex’s high-reward, high-merchant-fee products. The following hypothetical illustrates this issue.

Assume a single department store patron owns three payment cards and is contemplating a $100 purchase. Card A charges merchants a 3.5 percent discount fee per transaction, which reduces the merchant’s revenue by $3.50 to $96.50.217 Cards B and C charge merchants 2.5 percent and 2 percent per transaction, respectively. A merchant benefits by accepting all three cards because this increases its ability to attract customers who will, in turn, increase gross revenue. In particular, Card A offers high rewards, and its users enjoy this benefit. If the merchant operates in a competitive market, accepting Card A is an important step toward getting these patrons in the front door.

Now assume merchants can steer patrons in keeping with the merchants’ own incentives.218 When a patron attempts to make the $100 purchase with Card A, the merchant faces a $3.50 fee. If, at the point of sale, it were able to persuade the patron to use Card B instead, the merchant could benefit from Card A’s patron base while saving itself the difference between the 3.5 percent and the 2.5 percent fees, namely $1.219 However, the patron may not be willing to use Card B voluntarily: Card A’s high merchant discount fee likely finances superior customer rewards. Say the patron values these rewards at $0.80. With an eye toward maximizing short-run profits, the merchant could propose the following trade: in exchange for the patron using Card B, the merchant would rebate the patron some award valued at between $0.81 and $0.99. In this way, both the patron and the merchant benefit.220

The gains to trade experienced by the merchant and the patron have a clear loser: Card A. In a world in which merchants are allowed to steer at the point of sale, the fraction of consumers using Card A declines.221 Eventually, Card A faces one of two choices: (1) it could reduce its 3.5 percent fee in order to compete at the point of sale with Card B, or (2) it could discontinue operations. If there are no productive efficiencies to be gained, reducing the 3.5 percent fee must come from reducing rewards to Card A cardholders or charging them a higher fee. If Card A cuts back on rewards to its cardholders, the merchant can simply change the terms of its proffered trade with the patron until Card A either charges a 2.5 percent fee or drops out of the market. However, even if Card A stays in the market, Card C has a 2 percent fee, while Cards A and B now charge 2.5 percent. The problem is iterative, and one might expect all three cards to converge at a similar fee.222

The long-run effect of point-of-sale steering, then, is to either decrease the number of competitors in the market or decrease the differentiation among competitors. Decreasing either product differentiation or the quantity of competitors runs counter to the goals of antitrust enforcement.223 The antisteering provisions might thus be viewed as combating three undesirable situations: (1) all competitors dropping out of the market and a return to the historical transaction-cost problem;224 (2) all competitors but one dropping out of the market, resulting in a pure monopoly; and (3) some number of competitors remaining in the market, but with scarcely differentiated products. For Cards A and B, then, antisteering provisions would plausibly ensure continued availability of the platforms’ differentiated products, thus clearing stage two’s hurdle.

The hypothetical helps shed light on why, in Amex, Visa and MasterCard may have settled out of court while Amex did not: antisteering provisions in Visa’s and MasterCard’s hands would likely not be platform preserving.225 This is because, in reality, Visa and MasterCard are similar enough in features and fees to both play the role of Card C. As the low-feature, low-price counterpoints to Amex’s high-reward, high-merchant-fee product, they would likely have been the beneficiaries of merchants’ steering behavior. The hypothetical also helps explain why the Second Circuit was correct in accepting multisidedness as part of market definition in Amex and excluding it in Visa. As to Amex, Card A represents Amex, and it had recourse to the preservation argument discussed above. As to Visa, recall that Visa’s and MasterCard’s platforms include a layer of intermediary banks and that the challenged conduct in Visa implicated exclusivity rules prohibiting these banks from issuing Amex and Discover cards.226 These rules did not seek to preserve product differentiation over time. Merchants had not attempted to free ride on benefits while skirting burdens. No one attempted to arbitrage the platform’s market. Visa’s and MasterCard’s rules merely sought to exclude Amex from competing for certain customers. Turf battles of this sort constitute plain old exclusive behavior.

Conclusion

Whether a court should incorporate one or more sides of a multisided platform during antitrust market definition is a thorny matter. Definitions that include all sides of the platform create a broader space of allowable pro- and anticompetitive trade-offs than definitions that include fewer sides. Because the result of this inquiry often dictates the outcome of the case, plaintiffs and defendants have incentives to propose markedly different definitions. Courts, in turn, have varied on whether and how to incorporate evidence of multisidedness in the definitional process. Yet the challenge posed by multisided platforms may be addressed methodologically, and this Comment suggests one approach. Its contribution is the development of a test designed to help courts know when to disregard or accept arguments concerning the applicability of multisidedness to market definition.

Because antitrust operates at the juncture of case law and economics, any would-be test must be faithful to both. This Comment argues that the test factors best suited to the fine-grained and flexible analysis mandated by Kodak, Times-Picayune, and Grinnell are the primitives from which applied theorists build industrial organization models of multisidedness. This Comment identifies these factors and adapts them for judicial usage. Of note, the test proposed herein provides an alternative to definitional characterizations based on the horizontal or vertical nature of the challenged restraint. When these directional distinctions tell an incomplete tale, the Comment’s test permits analysis of multisidedness without recourse to directionality. This is all the more important in an environment in which advances in economic and statistical methodology permit finer-grained analysis and novel business methods challenge traditional notions of industrial organization.

- 12017 WL 2444673 (US). For the decision below, see United States v American Express, 838 F3d 179, 188–89 (2d Cir 2016) (“Amex”).

- 2See text accompanying note 83 (defining a platform as a business method that enables interactions between distinct groups, each of which cares about the extent of the other group’s participation).

- 3See text accompanying notes 85–89.

- 4See Marc Rysman, The Economics of Two-Sided Markets, 23 J Econ Persp 125, 125, 129–31 (Summer 2009) (asserting that both video game systems and payment cards are examples of multisided platforms).

- 5See E. Glen Weyl, A Price Theory of Multi-sided Platforms, 100 Am Econ Rev 1642, 1642–43 (2010) (describing credit cards and newspapers as canonical examples of multisided platforms).

- 6See notes 97–98 and accompanying text.

- 7See Rysman, 23 J Econ Persp at 129 (cited in note 4).

- 8See notes 136–37 and accompanying text.

- 9See notes 109–10 and accompanying text.

- 10See Black’s Law Dictionary 1113 (Thomson Reuters 10th ed 2014) (defining a market as a “place of commercial activity in which goods or services are bought and sold”).

- 11Id at 1115 (defining a relevant market as simply “a market that is capable of being monopolized”).

- 12NYNEX Corp v Discon, Inc, 525 US 128, 135 (1998).

- 13Directorate for Financial and Enterprise Affairs Competition Committee, Market Definition *321 (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Oct 11, 2012), archived at http://perma.cc/5QVX-AJ8Y (emphasis added).

- 14351 US 377 (1956).

- 15Id at 379.

- 16Id at 399.

- 17See id at 400, 403–04. See also text accompanying notes 76–77 (exploring problems with the Cellophane Court’s approach).

- 18See 15 USC § 15a (creating standing for the United States); 15 USC § 15c (creating standing for the states); 15 USC § 15 (creating private standing). See also Brunswick Corp v Pueblo Bowl-o-Mat, Inc, 429 US 477, 489 (1977) (explaining that a private plaintiff’s standing requires “prov[ing] antitrust injury, which is to say injury of the type the antitrust laws were intended to prevent and that flows from that which makes defendants’ acts unlawful”).

- 1926 Stat 209 (1890), codified as amended at 15 USC § 1 et seq.

- 2038 Stat 730 (1914), codified as amended at 15 USC § 12 et seq.

- 2138 Stat 717 (1914), codified as amended at 15 USC § 45 et seq.

- 22See Antitrust Division Workload Statistics FY 2006–2015 *1 (DOJ, July 8, 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/UDU2-XF2X. During fiscal years 2006 to 2015, the DOJ’s Antitrust Division initiated 511 Sherman Act § 1 restraint-of-trade investigations, 19 Sherman Act § 2 monopoly investigations, and 789 Clayton Act § 7 merger investigations. In the same time period, it brought only 81 investigations under other statutes. Id. The FTC investigates Sherman and Clayton Act claims by way of the FTC Act § 5. See Times-Picayune Publishing Co v United States, 345 US 594, 609 (1953) (stating that an “arrangement transgresse[d] § 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act, since minimally that section registers violations of the Clayton and Sherman Acts”).

- 23See Brown Shoe Co v United States, 370 US 294, 324 (1962) (explaining that the “‘area of effective competition’ must be determined by reference to a product market . . . and a geographic market”).

- 24Black’s Law Dictionary at 1114 (cited in note 10).

- 25Id. For example, if a creamery’s decision to raise butter prices would prompt consumer substitution to margarine, the firm’s ability to raise prices is constrained, and the product market might include both butter and margarine.

- 26Id (“If a firm can raise prices or cut production without causing a quick influx of supply to the area from outside sources, that firm is operating in a distinct geographic market.”).

- 27Sherman Act § 1, 26 Stat at 209, 15 USC § 1.

- 28State Oil Co v Khan, 522 US 3, 10 (1997) (emphasis added).

- 29See, for example, Bhan v NME Hospitals, Inc, 929 F2d 1404, 1410 (9th Cir 1991).

- 30See id at 1410, 1413 (“To determine whether a practice unreasonably restrains trade, . . . [t]he focus is on . . . competition in a relevant market.”). Part I.B discusses a class of restraints for which market definition is not necessary. Such restraints are presumed anticompetitive, and defendants do not receive the contextual benefit of framing the alleged harm in a favorably scoped relevant market. See text accompanying notes 47–50.

- 31Black’s Law Dictionary at 1532 (cited in note 10). See also Continental TV, Inc v GTE Sylvania, Inc, 433 US 36, 49 (1977) (stating that, under the rule of reason, courts weigh “all of the circumstances of a case in deciding whether a restrictive practice should be prohibited as imposing an unreasonable restraint on competition”).

- 32Capital Imaging Associates, PC v Mohawk Valley Medical Associates, Inc, 996 F2d 537, 543 (2d Cir 1993) (emphasis omitted).

- 33See Concord Associates, LP v Entertainment Properties Trust, 817 F3d 46, 54 (2d Cir 2016).

- 34Capital Imaging, 996 F2d at 543.

- 35See, for example, United States v Visa U.S.A., Inc, 344 F3d 229, 238–39 (2d Cir 2003) (adopting the plaintiff’s assertion that the product market consisted of general-purpose payment cards and rejecting a broader market proposed by the defendants consisting of cash, checks, debit cards, and credit cards).

- 36Capital Imaging, 996 F2d at 543.

- 37Sherman Act § 2, 26 Stat at 209, 15 USC § 2.

- 38384 US 563 (1966).