Judge Diane P. Wood: A True Friend

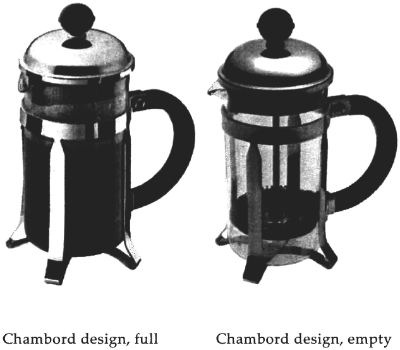

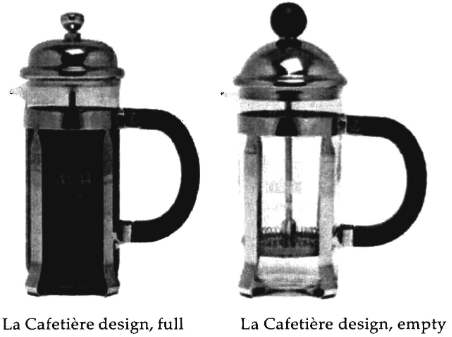

Bodum USA, Inc. v. La Cafetiere, Inc. is a case about French press, trade dress, and a twenty-year-old contract. Although those aspects of the case gave then-Chief Judge Frank Easterbrook the opportunity to include in his opinion images of the competing French-press coffee makers, they are not the part of the case that has lived on. On the bench for Bodum were the “Chicago Three”—Judges Easterbrook, Richard Posner, and Diane Wood. The case was argued in the first few weeks of my clerkship with Judge Wood, and it was a thrill for me to see them in action. Oral argument was not the end of their trialogue: Each issued a separate opinion in Bodum to address an issue tangential to the merits. Judges Easterbrook, Posner, and Wood wrote separately to discuss how federal courts should ascertain the content of foreign law. In so doing, Judge Wood displayed the combination of intellect, humility, and fantastic writing that make her the towering figure that she is.

The competing French presses, from Judge Easterbrook’s opinion.

The dispute in Bodum turned in part on an issue of French law, on which the parties submitted expert declarations under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 44.1.1 Judge Easterbrook rejected the declarations in favor of written sources in English, remarking that “[t]rying to establish foreign law through experts’ declarations not only is expensive (experts must be located and paid) but also adds an adversary’s spin, which the court then must discount.” Judge Posner wrote separately to “express emphatic support for, and modestly to amplify” Judge Easterbrook’s position. Judge Posner explained: “I cannot fathom why in dealing with the meaning of laws of English-speaking countries that share our legal origins judges should prefer paid affidavits and testimony to published materials,” and “[i]t is only a little less perverse for judges to rely on testimony to ascertain the law of a country whose official language is not English, at least if [it]2 is a major country and has a modern legal system.”3 Confident in their abilities to read and evaluate written sources on French law, Judges Easterbook and Posner saw no need to rely on expert testimony.

Judge Wood had other ideas. I was tempted, at this point, to simply quote in its entirety Judge Wood’s concurring opinion—but then I remembered Judge Wood’s advice about concision. Here is how Judge Wood’s opinion begins:

While I endorse without reservation the majority’s reading of the 1991 contract that is at the heart of this case, I write separately to note my disagreement with the discussion of Fed. R. Civ. P. 44.1 in both the majority opinion, and in Judge Posner’s concurring opinion. Rule 44.1 itself establishes no hierarchy for sources of foreign law, and I am unpersuaded by my colleagues’ assertion that expert testimony is categorically inferior to published, English-language materials. Exercises in comparative law are notoriously difficult, because the U.S. reader is likely to miss nuances in the foreign law, to fail to appreciate the way in which one branch of the other country’s law interacts with another, or to assume erroneously that the foreign law mirrors U.S. law when it does not. As the French might put it more generally, apparently similar phrases might be faux amis. A simple example illustrates why two words might be “false friends.” A speaker of American English will be familiar with the word “actual,” which is defined in Webster’s Third New International Dictionary as “existing in act, . . . existing in fact or reality: really acted or acting or carried out—contrasted with ideal and hypothetical . . . .” So, one might say, “This is the actual chair used by George Washington.” But the word “actuel” in French means “present” or right now. A French person would thus use the term “les événements actuels” or “actualité” to refer to current events, not to describe something that really happened either now or in the past.4

Judge Wood then explained the ways that expert testimony might be useful, efficient, and testable in court. She did not, however, reject the methods of Easterbrook and Posner: “The written sources cited by both of my colleagues throw useful light on the problem before us in this case, and both were well within their rights to conduct independent research and to rely on those sources. There is no need, however, to disparage oral testimony from experts in the foreign law. That kind of testimony has been used by responsible lawyers for years, and there will be many instances in which it is adequate by itself or it provides a helpful gloss on the literature.”5

Judge Wood is an intellectual heavyweight.6 She spent years working on international issues that required deep engagement with foreign law.7 She is fluent in French.8 If anyone on the federal bench would have been qualified to ignore expert testimony on French law and conduct independent research on its content, it would have been Judge Wood. But Judge Wood knows enough to know the risks of that enterprise. And despite her countless accomplishments,9 Judge Wood has retained an intellectual humility that is uncommon among lifetime appointees.

More generally, the Judge Wood on display in Bodum is what we dream of in a judge, and it reflects the Judge Wood I observed doing her job every day. First, Judge Wood’s opinion in Bodum asks judges to be open-minded and voracious consumers of information. Rule 44.1 refers to “any relevant material or source.”10 As the consummate proceduralist, Judge Wood took those words to heart in Bodum. Judge Wood considers “any relevant material or source” in all of her judging. Her landmark opinion in Bloch v. Frischholz (7th Cir. 2008) (the “mezuzah case”), was based on a scouring of the judicial record, not a mere reliance on the parties’ briefs.11 I can testify from personal experience that Judge Wood’s interest in the record was not limited to a high-profile case or two.12

Second, Judge Wood’s opinion in Bodum was humane. She does not go in for disparaging parties or witnesses; she does not impugn her colleagues; and she is not the sort of judge to add a cute analogy to an opinion addressing the worst day of someone’s life. Indeed, Judge Wood would go out of her way in opinions and at argument to try to help solve problems—sometimes problems created by the law she was compelled to apply.13

Third, the writing is fantastic.14 Judge Wood is renowned for her writing.15 Her opinions are frequently selected to appear in The Green Bag’s annual publication of “Exemplary Legal Writing,” including her opinion in Bodum.16 The Green Bag also honored two of Judge Wood’s articles, as she found time to write leading scholarship while also being a federal judge and a lecturer at the University of Chicago.17

* * *

More than twenty years ago, Judge Wood delivered remarks at Hastings Law School about her former boss, Justice Harry Blackmun. I did not know Justice Blackmun, but I know Judge Wood, and I cannot think of a more appropriate description of my former boss:

It is characteristic of [Judge Wood] not to be swept away by the superficial trappings of the position, not to be intoxicated by the power the Court wields, and not to view the relentless flood of cases as a private intellectual game. For [her], the salient feature of the position of [federal judge] was the profound responsibility [s]he bore to the litigants, to the Court as an institution, to the legal community, and ultimately to the people of the United States.18

Thank you, Judge Wood, from all of us.

- 1Fed. R. Civ. P. 44.1 (“A party who intends to raise an issue about a foreign country’s law must give notice by a pleading or other writing. In determining foreign law, the court may consider any relevant material or source, including testimony, whether or not submitted by a party or admissible under the Federal Rules of Evidence. The court’s determination must be treated as a ruling on a question of law.”). For an historic treatment of the Rule, see Arthur Miller, Federal Rule 44.1 and the “Fact” Approach to Determining Foreign Law: Death Knell for a Die-Hard Doctrine, 65 Mich. L. Rev. 613 (1967). And for my own continued interest in this topic, see generally Brief of Professors of International Litigation as Amici Curiae in Support of Neither Party, Animal Science Products, Inc. v. Hebei Welcome Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., No. 16-1220 (Mar. 2, 2018), 2018 WL 1202844.

- 2As any good Wood clerk would, I confirmed all quotations from Westlaw in the Federal Reporter, so I can say with confidence that the “it” was missing from this sentence.

- 3Bodum, 621 F.3d at 633 (Posner, J. concurring).

- 4Bodum, 621 F.3d at 638–39 (Wood, J., concurring) (citations omitted).

- 5Bodum, 621 F.3d at 639 (Wood, J., concurring) (citations omitted).

- 6Self-evident.

- 7Although Judge Wood would not stoop to this type of sourcing, I will note that the word “international” appears on her CV 156 times.

- 8See, e.g., Institute of Judicial Administration, Oral History of Distinguished American Judges, Chief Judge Diane P. Wood (link).

- 9See Diane P. Wood, Senior Lecturer in Law, The University of Chicago Law School (linking to Judge Wood’s 44-page CV) (link).

- 10Fed. R. Civ. P. 44.1.

- 11See 533 F.3d at 566–74 (Wood, J., dissenting). For another example, see the extensive historical analysis in Judge v. Quinn, 612 F.3d 537 (7th Cir. 2010) (surveying the history of the Seventeenth Amendment).

- 12See Late Nights in Chambers (7th Cir. 2009–2010).

- 13For example, in Aguilar-Mejia v. Holder (7th Cir. 2010), Judge Wood felt compelled to deny a petition for review of an immigration decision, but she concluded the opinion by identifying (for the petitioner and for the government) various tools available that might allow the petitioner to stay in the United States to receive life-sustaining medical care. Id. at 704–05 (“Although we must deny Aguilar–Mejia’s petition, we close by noting that we are aware of the exceptional humanitarian concerns raised in this case. PML is an extremely serious disease; Aguilar–Mejia’s condition is severe, and could rapidly deteriorate if he loses his access to the antiretroviral therapy discussed by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, supra. (Even with state-of-the-art therapy, his chances of survival over the next year may be only 50–50.) Because he is not only HIV-positive but also suffers from full-blown AIDS, Aguilar–Mejia also needs medication that is likely not to be available to him if he is removed. Missing his medication for even a brief period could be a literal death sentence. As the IJ noted, ‘almost all of [Aguilar–Mejia’s] witnesses testified that . . . the treatment [for AIDS] is not easily accessed and not readily available’ in the countries designated for removal. For these reasons, we respectfully encourage the Attorney General, if asked by Aguilar–Mejia, to consider ‘deferred action,’ ‘humanitarian parole,’ or any other discretionary remedy that may be granted on humanitarian grounds.”).

- 14Res ipsa loquitur.

- 15See, e.g., Bill Baer, Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division, U.S. Department of Justice, Presentation of the John S. Sherman Award to the Honorable Diane P. Wood at 2 (Nov. 13, 2015) (“Mother Jones referred to [Judge Wood] as ‘a rock star of the written word.’ I am not sure what that means. But it sounds really cool.”).

- 16See The Green Bag Almanac of Useful and Entertaining Tidbits for Lawyers for the Year to Come & Reader of Exemplary Legal Writing from the Year Just Passed (honoring, inter alia, Judge Wood’s opinions in Dassey v. Dittmann, 877 F.3d 297 (7th Cir. 2017) (en banc) [pronounced “in bank”]; Empress Casino Joliet Corp. v. Johnston, 763 F.3d 723 (7th Cir. 2014); Bodum USA, Inc. v. La Cafetiere, Inc., 621 F.3d 624 (7th Cir. 2010); Gore v. Indiana University, 416 F.3d 590 (7th Cir. 2005)).

- 17See id. (honoring inter alia Diane P. Wood, When to Hold, When to Fold, and When to Reshuffle: The Art of Decisionmaking on a Multi-Member Court, 100 Calif. L. Rev. 1445 (2012); Diane P. Wood, Original Intent versus Evolution: The Legal-Writing Edition, The Scrivener (Summer 2005)). It was a professional honor when I was able to publish an article in The Green Bag on a topic near to Judge Wood’s heart (and mine), personal jurisdiction. See generally Zachary D. Clopton, Long Arm “Statutes”, 23 Green Bag 2d 89 (2020).

- 18Remarks of Judge Diane P. Wood, Justice Harry A. Blackmun and the Responsibility of Judging, 26 Hastings Const. L.Q. 11, 12 (1998) (from Symposium: The Jurisprudence of Justice Harry A. Blackmun).