The Perils of Poor Penmanship: A D.C. Circuit Fight Demonstrates the Urgency of Electronic Union Elections

Introduction

The legibility of handwriting is on the decline. Thankfully, calligraphy carries low stakes in a digital age. Why write something down when it can be typed instead? Yet, there is still one near-universal fragment of writing that must often be done by hand: the signature. While usually a formality, so long as signatures are done by hand, they can be second-guessed, threatening a generation untrained in cursive.

This Essay highlights a recent incident in which a union representation election hinged on the legibility of one employee’s signature. It will explain how the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, while upholding the validity of the signature, did not go far enough in safeguarding future representation elections from the crisis of cursive. Further, this Essay argues that this entire issue would be obviated if Congress permitted the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which officiates most labor union representation elections in the private sector, to use the electronic voting system currently under development by the National Mediation Board.

I. The Long March at Longmont

In April 2022, the NLRB certified that a group of registered nurses at Longmont United Hospital (Longmont) had voted to be represented in collective bargaining by a labor union, the National Nurses Organizing Committee/National Nurses United (NNOC/NNU). Ninety-four nurses had voted in favor of union representation; ninety-three had voted against.

Longmont, wishing to challenge the results of the election, refused to negotiate with NNOC/NNU, forcing the union to file an unfair labor practice charge with the NLRB. The NLRB concluded that the election had been conducted correctly and ordered the parties to bargain. Longmont then appealed the NLRB’s order to the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. In June 2023, over a year after the election, the court affirmed the legitimacy of the election result in Longmont United Hospital v. NLRB, sending the parties back to the bargaining table.

A. Victory at the D.C. Circuit

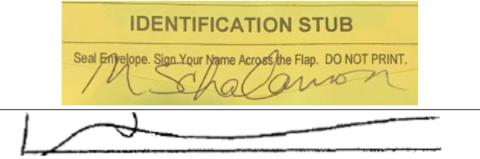

The election at Longmont had been conducted by mail. NLRB regulations require that voters sign the outer envelope containing their ballot. Ballots “with names printed rather than signed” are void. To overturn the result of the election, Longmont argued that Mysti Schalamon, a nurse who had voted in favor of union representation, had not technically signed her ballot. All parties agreed that Schalamon had cast her ballot, but Longmont argued that her name on the envelope had been written in print. To support its accusation, Longmont produced sixteen documents signed by Schalamon in the course of her employment. She had signed each with “a swooping ‘M’ followed by a long line trailing off to the right.” In response, NNOC/NNU produced Schalamon’s driver’s license and Social Security card. Both records contained signatures that more closely resembled the one on her ballot: “a printed capital ‘M’ followed by her last name written using a capital block-letter ‘S’ followed by the rest of the letters in cursive.” The below image, taken from Longmont’s brief to the D.C. Circuit, shows the signature that appeared on Schalamon’s ballot and one of the examples taken from her employment records.

Schalamon testified that she uses two different signatures: she scribbles the “M” Longmont identified “when she is ‘in a hurry,’” but otherwise signs documents by writing out her first initial and last name. She stated that the latter style appeared on her ballot. The NLRB Regional Director who had supervised the election credited Schalamon’s testimony and denied Longmont’s challenge to her ballot.

The D.C. Circuit could not find any basis on which to overrule the Regional Director’s determination. Longmont argued both that the NLRB had disregarded its own precedent barring consideration of postelection testimony and that Schalamon’s testimony was not credible. The court determined that the NLRB had no such precedent and that Longmont failed to produce any evidence relevant to Schalamon’s reliability.

B. The Limits of the Court’s Decision

While the D.C. Circuit handed a victory to the union, it did not resolve a fundamental issue that the NLRB had raised in its brief. If all parties admit that an eligible voter cast a ballot, does the validity of that voter’s signature matter? The NLRB argued that “the proper inquiry is whether the ballot was in fact cast by the employee for whom it was meant,” not whether the signature was written in cursive.

The court admitted that the Regional Director supervising the election “found any inconsistency with past signature samples immaterial in the absence of any question as to the voter’s identity,” but did not endorse her interpretation of the law. By resolving the case on the narrower ground that the NLRB had properly determined that Schalamon’s mark was her signature, the court left future elections open to similar challenges. Instead, the D.C. Circuit should have agreed with the NLRB’s interpretation of its own regulations and ruled that an employer may only prevail in a challenge to an employee’s signature if the employer can prove that the employee did not actually cast the ballot in question. The risk of courts continuing down the current path is that, as knowledge of cursive is lost, employees will be disenfranchised in future union elections by signing their ballots with a signature that is indistinct, inconsistent, or in print.

II. Modernizing Union Representation Elections

A. Vote by Mail is Inadequate

Union representation elections have been conducted by mail since at least 1936, the year after the NLRB was formed. Labor law has strongly favored in-person elections. But, as with many other routine government procedures, that preference changed after the COVID-19 pandemic. The NLRB instituted a brief moratorium on union representation elections in March 2020 and conducted more than 90% of its elections over the subsequent months by mail, loosening its standards for remote elections. However, so long as mail remains the only alternative to in-person elections, the issue with signatures will loom over the NLRB’s procedures. While the Longmont case may seem unusual, when potential bargaining units are small, it is not difficult for the employer to challenge enough signatures to force an extended hearing and appeals process,1 delaying employees’ enjoyment of the benefits of labor union representation.

Besides allowing employers to challenge signatures, mail elections come at another cost: lowered turnout. The turnout rate for union representation elections conducted by mail was just under 60% in 2009; in comparison, it was over 80% for elections conducted in-person. For example, in the most recent runoff elections for the President of the International Executive Board of the United Autoworkers (UAW), approximately 140,000 members out of an active membership of more than 400,000 cast ballots, resulting in a turnout of only 35% in an election that was decided by fewer than 500 votes.

This is not to say that the UAW, or any union, should conduct internal elections in person. The UAW, in particular, does not have the infrastructure to do so across its vast geographic scope. And its previous method of selecting its leadership, a national convention, was rife with corruption and self-dealing.

B. Voting Without Signing: Electronic Elections

There is an alternative election method that does not suffer from the same shortcomings as vote by mail: electronic voting. Electronic union representation elections have been a longstanding policy goal of both the NLRB and unions. In January 2011, the NLRB sought public comment on “guidelines concerning the use of electronic voting systems in union officer elections.” But it was forbidden by subsequent legislation from moving forward with its plans. In response to uncertainty created by the COVID pandemic, a coalition of labor organizations and members of Congress sent a letter to congressional leadership requesting funding for the NLRB to develop an electronic system for union representation elections. This push for electronic union elections was opposed by anti-labor groups who mobilize specious concerns about privacy and intimidation. But, by shortening the campaign period before elections, electronic voting would likely make voter intimidation by both unions and employers more difficult.

In addition, electronic voting would obviate the need for signature verification. Under the NLRB’s previous proposal, each voter would be assigned a unique Voter Identification Number (VIN) to enter when casting their vote. Votes would be cast either through an online portal or through an automated telephone system. The use of VINs would ensure that each voter could only cast one vote while making sure each vote was cast by a registered voter. This is the same procedure currently used by the Missouri State Board of Mediation to conduct electronic union elections for public employees.

While policymakers should authorize electronic voting in union representation elections and union officer elections, they should be wary of expanding it to higher-stakes elections such as those for state or federal office. Estonia has permitted electronic voting in its parliamentary elections since 2005. But cybersecurity experts have recommended that Estonia discontinue this system because it is vulnerable to state-sponsored attacks. Union elections, on the other hand, are less likely to be of interest to sophisticated attackers because they are less important. And union elections are more easily audited than political elections because they are much smaller scale. In 2023, the median union election had only 21 eligible voters.

Thankfully, if it gets the green light, the NLRB does not have far to look for a viable model of electronic voting. The National Mediation Board (NMB), which supervises union elections for railroad and airline workers, has conducted elections by telephone since 2002 and by internet since 2007. The NMB has developed new election methods and iterates frequently on them because the electorates it supervises are often national in scope and made up of voters who spend much of their time traveling for work. Currently, the NMB is in the process of developing its own in-house electronic voting system. Hopefully, once this is complete, the government-operated system could easily be adapted to the NLRB’s purposes.

Conclusion

To avoid another case like Longmont, which deprived hundreds of workers of union representation for over a year, both Congress and the executive branch should act quickly to make electronic union elections a reality. Congress must lift its prohibition on them and the NLRB and NMB must work together to develop a robust and secure electronic voting platform.

* * *

Noah del Rio Levine is a J.D. Candidate at the University of Chicago Law School, Class of 2025. He thanks the University of Chicago Law Review Online team for their careful feedback.

- 1See generally, for example, College Bound Dorchester, Inc. (2021) and Thompson Roofing, Inc. (1988).