Slicing (and Transferring) Development

Introduction: Lumpy Depth

Spend too long within the pages of Lee Fennell’s Slices and Lumps and you begin to see slices and lumps everywhere. The deadline for this Essay fast approaches and I fear I will not have enough time to devote to it. Sure, there are slices of time I can carve out between class preparation, student and faculty meetings, housework, and picking up my son from school. All together they may add up to the hours needed to do the book justice with an essay worthy of its content and author. But really what I need are lumps—long, uninterrupted periods of time to devote myself to the task, far from the madding slices of distraction that collectively consume a day.

Such lumps are one way to achieve the focus and attention necessary for deeper and more creative work. Cal Newport, the author of a very different book on aggregation, calls this state Deep Work. As Fennell herself remarks, such uninterrupted periods may enable “cumulative inputs that build on each other,” reducing “time spent ramping up and ramping down” (pp 121–22). But then again, as Newport also suggests, if I am sufficiently submerged in and consumed by a given task, insights might come to me at unexpected moments: the walk to work or the time waiting for a bus. I then must try to aggregate these tiny slices into the 4,000 or so words I have been asked to write. What follows is my attempt to do so.

I will say at the outset that I struggled a bit in deciding what to discuss in this short essay. Slices and Lumps sheds new light on a number of topics I have explored in prior work, particularly around the sharing (or slicing) economy, the configuration of housing into smaller units such as micro-units and accessory dwelling units, and the bundling of federal housing assistance into optimal benefit lumps. However, rather than discuss any of these, I decided to use Slices and Lumps to reconsider a topic Fennell does not touch on directly in her far-reaching text: transferable development rights (TDRs). At the start of my academic career, I explored TDRs in a symposium piece co-authored with Vicki Been. We discussed multiple themes that relate directly to Slices and Lumps: the transformation of unused development capacity into transferable rights, the proper scale at which to consider zoning and the density of development, and how the configuration of property rights can shape cities. TDRs, for reasons I hope will soon become clear, provide an ideal vehicle for considering the interaction of slices and lumps, the advantages (and disadvantages) of slicing entitlements, and the relationship between what might be termed naturally occurring lumps and the artificial lumps created by law. Accordingly, Part I of this essay first introduces the concept of transferable development rights before exploring the aforementioned themes in greater detail. Part II then broadens the discussion to consider how the conceptual frame of slices and lumps might help us in evaluating recent high-profile zoning reforms and the potential for further reform.

I. Slicing and Lumping Development

A. A Bit on TDRs

First, a bit of background. Transferable development rights programs enable an owner of property that is not developed to its full zoning capacity to transfer all or some portion of the right to develop that land to another parcel. They thereby slice traditional lumps of development capacity, which are no longer inextricably linked to a particular parcel of land. The unused slices of development rights at a grantor site can then be moved to a receiving parcel. This enables the recipient to develop at a higher capacity than otherwise permitted under the applicable zoning regulations. Such transfers lead—potentially—to a more efficient allocation of development rights.

A granting parcel may be developed below the allowable capacity (leaving unused development rights) due to a historic preservation ordinance or environmental regulation, or because the owner has simply chosen not to develop to the full permitted capacity. TDR programs allow these property owners to recoup some of the value of this unused capacity through the sale of a slice or slices of development rights on the private market.

In the urban context, the transfer of development rights typically occurs on a one-to-one basis, with transfers taking the form of a specific number of square feet of floor area. For example, in New York City, the primary mechanism for regulating the size of a building is floor area ratio. The floor area ratio is multiplied by the area of a given lot, resulting in the number of square feet permitted for a building on that lot. It is the unused square feet of development that can subsequently be transferred to a different lot. There are multiple different TDR programs in New York, as well as more than two hundred programs across the country. They function in a variety of ways and serve a range of purposes, including historic preservation, farmland preservation, the development of affordable housing, and broader urban design and revitalization goals.

In some instances, parcels with unused capacity—which sometimes are referred to as soft sites—may not be subject to a regulatory restriction that prohibits new or expanded development on site. A property owner may simply choose not to use this unused capacity for a number of reasons, some of which relate to the lumpiness of an existing building. A large building developed to 80 or 90 percent of its maximum allowable size may have a significant number of unused development rights (perhaps tens of thousands of square feet of development). However, adding that capacity to the existing building might be structurally or financially impossible, and demolishing and rebuilding on site may prove less financially rewarding than continuing with the current use. The cost of moving from one lump to another might, therefore, discourage further development on site. Other reasons for not redeveloping stem from the slicing of ownership. A condominium building may have significant unused development rights, but the existing owners of individual units do not wish to move out and demolish and rebuild their homes. This slicing of ownership renders the movement from one lump of development to a larger one difficult or impossible.

Absent development rights transfers, any unused capacity is likely to remain idle. Development rights transfers enable the aggregation of these slices with other transfers and with the available capacity at a given receiving site (which may be vacant or more likely itself a soft site), resulting in the potential for the owner of the recipient site to move to a larger and more financially rewarding lump of development. In many cases, additional slices of development rights also provide the most financial reward for developers, who lump them on top of high-rise residential buildings along 57th street in New York City to produce “super tall” buildings in what has been termed Billionaires Row.

B. Density Zoning, or Determining the Proper Lump

TDR programs typically specify the geographic boundaries of the sites that can receive transfers. Recipient sites may be within the same designated area as sending sites or significantly distant (as in the case of farmland preservation programs). One of the most basic TDR mechanisms, New York City’s zoning lot mergers, allows for a set of contiguous, but separately owned, tax lots within a given block to be considered a single lot for zoning purposes. Unused development rights within the new zoning lot can then be used, as-of-right, anywhere within the zoning lot. Zoning lot mergers, then, reflect both slicing and lumping of property entitlements. For purposes of compliance with the Zoning Resolution, the relevant unit is the set of separately owned parcels legally lumped into a single zoning lot. But within that zoning lot, individual property owners are now free to trade around the slices of unused development rights they possess. More generally, the zoning lot merger provision effectively allows for the regulation of maximum permissible density at the block level, rather than at the level of an individual parcel.

This change in the lump subject to regulation brings us from New York to Chicago. For it was the challenge of preserving urban landmarks (and the deficiencies of New York’s cumbersome and underused landmark TDR program) that motivated John Costonis, over four decades ago, to propose what he termed the “Chicago Plan.” Costonis suggested a mechanism for preserving landmarks through designation of “a ‘development rights transfer district,’ an area within which the unused development rights of landmark sites could be transferred.” He emphasized that the districts would include recipient sites sufficiently close to the transferring landmarks, so as to enable the low-density landmarks to offset the increased density at recipient sites. Costonis described his Chicago Plan as “an instance of density zoning, which prescribes a maximum amount of bulk for an area as a whole and permits developers to concentrate or disperse that density on individual lots within the area in accordance with flexible site planning criteria.” Although the Chicago Plan was never adopted, elements of Costonis’ vision are reflected in modern TDR programs.

Another early proponent of TDRs, Norman Marcus, argued more forcefully that the individual lot was an arbitrary choice as the traditional unit of development control and that it failed to serve public interests. Marcus contended that, rather than a single lot, “any unit with commonly accepted boundaries” could provide the basis for regulating development. It is at the neighborhood level (or at some level larger than the lot) that most of the amenities that might affect what we perceive to be the optimal (or an acceptable) level of development are provided: public transportation, open space, schools, and businesses, among others. As such, the size of the lump that serves as the subject of most zoning regulations, the individual lot, relates in no clear way to the level at which we plan the infrastructure necessary for development.

C. Potential Benefits of Slicing (and Transferring) Development Rights

By enabling the aggregation of unused, but valuable, slices of development rights into larger lumps, a robust and easy-to-use development rights transfer program might reduce the pressure to maximize development at a given lot. By giving an owner confidence that they will have the opportunity to monetize their unused development capacity at some point in the future, TDRs might lead a property owner to build or maintain a smaller building than zoning permits, but one that better fits their own needs, available resources, or existing market demand. Development rights that are not lumped and fixed at the lot level, but instead can be sliced off and transferred to a separate property, as Fennell notes, also might better to serve to create “valuable clusters” of interaction, while enabling or sustaining the benefits Jane Jacobs ascribed to the “mixing together [of] diverse uses” (p 173, 177–78) In addition to helping preserve a desirable mix of uses and buildings, both old and new, the easy slicing of development rights could better serve to generate agglomeration benefits by providing property owners greater opportunity to make continuous, rather than one-off, choices “about levels of economic investment in an area” (p 179).

Finally, broader adoption by cities of TDR programs akin to New York’s zoning lot mergers can mitigate, to some extent, the assembly problems described in Slices and Lumps (p 181). The combination of ground parcels may still be subject to holdouts from landowners who possess part of a desired lumpy whole. But a developer who seeks to build vertically will likely have access to a larger number of slices from multiple potential sellers, making coordination less subject to the whims of a particular neighbor.

Designing the optimal system of TDRs, with the goal of generating urban agglomeration benefits, is beyond the scope of this short essay. As Fennell notes, it is not clear whether skyscrapers—the frequent product of a TDR regime—even facilitate the desired types of interactions, or that clustering uses vertically results in interactions akin to those facilitated by clustering along a street (pp 185–86). Further research on how different lumps of development produce agglomeration benefits and how different means for slicing and transferring development rights might allow for assembly into different lumps is needed.

D. Potential Costs of Slicing (and Transferring) Development Rights

Shifting density controls from the lot to the block level will not necessarily result in the same overall density in the area subject to regulation. Rather than simply shift where development occurs, TDRs have the potential to encourage greater actual built density than might occur were transfers prohibited. This should not be surprising, as one argument offered in support of TDR programs is that they give value to development rights that would otherwise go unused. This gets to a question at the core of so many of the slicing regimes discussed in Slices and Lumps. Do Uber and Lyft make use of existing capacity, or do they lure more vehicles to the street, increasing congestion on urban roads with finite capacity? The evidence seems pretty clearly to indicate that the latter is true.

Moreover, systemic slack can prove useful in certain instances, as Fennell notes (pp 96, 129). Admittedly, in the context of urban development, such slack does not allow for easy use in cases of exigency. A hotel cannot add a floor during the busy season and then eliminate it in the down season. But rather than provide a valuable reserve of potential additional capacity, such slack may represent, in the case of zoning, an underappreciated but vital component of the overall system. Whether consciously or not, those jurisdictions that permit some degree of as-of-right development may presume that a share of the existing development capacity will go unused. On this account a city might choose to give the market greater control over where precisely development occurs and (within some limits) how intense it will be. The assumption, however, may be that developers are not likely to develop or redevelop all sites to the maximum extent permitted and so significant development capacity will remain unused and expected density will be less than the maximum permitted.

In fairness, this concern is more significant in the unique case of New York City’s zoning lot mergers, which can be used throughout the city. In the case of more carefully designed programs, where development rights can only be used at designated receiving sites (where an increase in density is desired or deemed suitable given existing infrastructure and amenities), this concern is less salient.

II. Lumpy and Bespoke Lots

A. The Slicing of Today

As noted above, early discussions of TDRs as a form of density zoning emphasized the arbitrariness of using the individual lot as the traditional unit of development control. The costs of this approach have become increasingly apparent in recent years amid the housing shortage in many urban areas and calls for increasing density in residential neighborhoods. The situation may not be so dire that America’s future “depends on the death of the single-family home,” but it is the case that much of the land even in major cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle is zoned exclusively for single-family residences. Absent the unlikely scenario of significant rezoning of these areas into multi-family districts, the only feasible mechanism for increasing density in such neighborhoods is to slice these lumps in a manner that allows for more housing units.

Fortunately, such slicing is starting to occur as municipalities allow homeowners to add an accessory (or additional) dwelling unit (ADU) on their single-family property. This may take the form of an internal ADU that slices off some of the existing square footage to form a new, independent dwelling that can be separately rented. Or it may take the form of an external ADU (a backyard cottage) that effectively slices into smaller segments the minimum lot area for a separate dwelling. In practice, however, the single-family property with an ADU remains a single tax lot under common ownership, and the ADU cannot be sold off to a separate owner.

Minneapolis took a more drastic step in late 2018, allowing duplexes and triplexes to be built on previously single-family lots. Oregon soon followed suit, allowing duplexes (and in larger cities fourplexes) on single-family lots throughout the state. At the same time, the City of Portland’s proposed Residential Infill Project would limit the maximum square footage of single-family houses, but allow more square footage (by increasing the maximum floor area ratio) on the same lot if the owner builds multiple, smaller units. So property owners willing to slice their property into more units will be permitted a larger lump of total development, in hopes this will nudge them away from building that most unfortunate of housing lumps, a McMansion.

California recently passed legislation allowing both an internal and external ADU on single-family properties statewide. This came on the heels of a more high-profile measure that, among other things, would have allowed for multi-family buildings with up to four units on any single-family parcel. The measures that did pass—which allow the equivalent of a triplex on each parcel—may prove only slightly more modest in their effect on density. But their success appears partly attributable to the fact that, while it may lead to a comparable increase in population density, slicing an additional unit out of an existing structure remains far more palatable than allowing the construction of a new multi-family dwelling.

It remains possible that some of these efforts will be undermined by homeowners association rules that apply to existing property. Or they might fuel additional demand for such restrictions, motivating homeowners desirous of an exclusive single-family neighborhood to opt into an HOA. California has addressed this concern in part by passing a law that strikes homeowners association covenants that prohibit or unreasonably restrict the addition of an ADU. Elsewhere, it may be that provisions eliminating exclusively single-family zoning will, by increasing the total development capacity and hence the potential value of a parcel, force those who choose the lump of a single-family home (whether in or out of an HOA) to internalize the costs of lower density.

Beyond adding gentle density to single-family neighborhoods, Californians looking for ways to increase housing supply remain hopeful that bolder measures will eventually succeed. However the most high profile effort, SB 50, recently failed. The measure would have overridden local zoning, including density controls, certain height restrictions, and design standards that limit the number of units, to promote greater housing supply near transit and in “jobs-rich areas[s].” In an effort to address concerns regarding displacement due to development pressures, measures 50 denied zoning relief to properties occupied by renters within the previous seven years.

This approach reflects a traditional focus on the individual parcel as the proper unit for applying and enforcing zoning. I want to suggest that a future version of SB 50 might benefit from the inclusion of a TDR program that links restrictions on the development of rental buildings with the ability for the owners of such buildings to transfer some or all of the unused additional capacity created by an upzoning, rather than leaving it idle on site. Absent such a measure a transit-rich neighborhood with a disproportionate number of parcels occupied by ineligible rental buildings may see significantly less development than an otherwise comparable neighborhood with significantly fewer such parcels. Granting TDRs might make it more likely that density increases evenly across all neighborhoods where a measure like SB 50 applies while perhaps building support among owners of rental buildings, who would otherwise see no benefit from the measure.

B. Slices from the Past

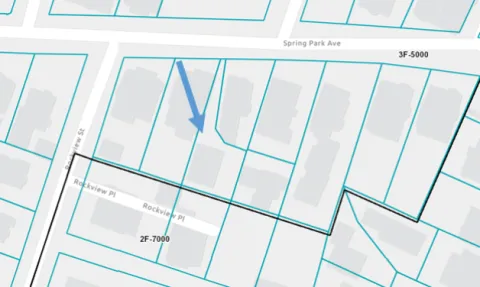

On our walk to school each morning, my son and I pass two rather quirky houses in our Boston neighborhood. We live in Jamaica Plain, a largely residential neighborhood six miles from downtown with an eclectic mix of triple-deckers, large old houses frequently divided into condos or apartments, apartment buildings, and single-family homes. The two houses of interest are each tucked behind other houses and situated on wildly irregular and seemingly bespoke slices of land. The address of the first, a 1,156 square foot home, is 37A, suggesting it was wedged at a later date between its neighbors, numbers 37 and 39 (Figures 1 and 2). Just two blocks away a roomier 1,852 square foot home bears the address number 69R, reflecting its position behind number 69, from which its own lot appears to have been sliced off (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Other examples like these abound in the neighborhood. What I find intriguing is that, while existing examples of slicing property in a way that allows for greater density (at the seeming cost of any significant buffer between homes) abound, the City of Boston only recently began to consider, and quite timidly promote, ADUs. As with so many development trends in Boston, it has done so in the most modest and cautious of fashions. The program prohibits external ADUs (which tend to be smaller than either of the two houses discussed above) and merely permits homeowners to carve out a small ADU within the existing envelope of their home.

It seems, then, that while there are many ways in which both law and life have, in recent years, increasingly embraced the slicing that Fennell describes, there remains a powerful tendency toward uniformity in property and land use law that inclines toward maintaining rigid lumps. Even as we may value the quirkiness of older neighborhoods where property lines are sliced and diced and a certain informality governs, there is a strong presumption in favor of maintaining the hard boundaries of present-day lumps. Such lumps provide seeming certainty, reinforcing the expectations and reliance interests of property owners. But this commitment to preexisting lumps can also lead to the rejection, either in law or in practice, of long acceptable forms of slicing that conferred desirable features on our urban landscapes.

Conclusion

Slicing, transferring, and aggregating development rights and recalibrating the scale or unit at which we apply density restrictions can enable new development and increase housing supply. They offer mechanisms for preserving a desirable variety of old and new structures and uses in urban neighborhoods by reducing development pressures on individual lots. At the same time, allowing the addition of new dwelling units to existing single-family lots minimally reconfigures existing lumps in a manner that may not upset the expectations of neighbors grown accustomed to the lumps next door and that may, in the aggregate, also make a significant contribution to the supply of housing. Slices and Lumps provides a rich and rewarding framework for thinking about the costs and benefits of these and other reconfigurations of our existing land uses and their regulatory regimes.