Reviewing Leniency: Appealability of 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) Sentence Modification Motions

In ordinary circumstances, criminal defendants get only one shot at sentencing. But in a few cases, defendants have a second chance at a more lenient sentence. This Comment considers one of those circumstances: motions under 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) for sentence reduction after retroactive downward adjustment of the Sentencing Guidelines. Specifically, this Comment considers the circuit split over when those motions are appealable. Courts disagree about which statute governs appellate jurisdiction: the general jurisdictional statute permitting appeal of any final decision of a district court (28 USC § 1291) or the specific sentencing jurisdictional statute restricting appeal of otherwise final criminal sentences (18 USC § 3742). This Comment proposes a novel solution: denials of eligibility are appealable under the general jurisdictional statute because they do not impose a new sentence, while grants or denials of leniency once eligibility has been found are appealable under the sentencing jurisdictional statute. Finally, this Comment proposes novel arguments for fitting appeals within the grounds of jurisdiction under the sentencing statute.

Introduction

Jose Rodriguez pled guilty to cocaine distribution and firearm charges in 2012.1 With a United States Sentencing Guidelines (USSG) range of 120–150 months in prison for his convictions, he was sentenced to 123 months’ imprisonment and 3 years’ supervised release.2 After Rodriguez’s conviction, the United States Sentencing Commission promulgated Amendment 782, effective in 2014, to retroactively reduce the Guidelines levels for drug trafficking offenses like Rodriguez’s.3 Rodriguez’s sentence was correct at the time he was sentenced; but had he been sentenced just two years later, his Guideline offense level would have been two levels lower, resulting in a lower sentencing range.4

Congress has provided recourse in 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) for the many criminal defendants who find themselves in Rodriguez’s position. That statute permits a defendant to move for a sentence reduction in the wake of a retroactive Guidelines amendment that would reduce his sentence—like the 2014 crack cocaine reduction. When Rodriguez filed such a motion in 2016, the district court found that he was eligible for a sentence reduction but exercised its discretion to deny the reduction.5 Rodriguez appealed.6

Rodriguez’s path thus far has been uncontroversial. But the circuits diverge on whether they have jurisdiction over appeals from the district courts’ decisions on § 3582(c)(2) motions and on which statute grants that jurisdiction. Defendants are not constitutionally entitled to benefit from downward Guidelines revisions, nor are they constitutionally entitled to sentencing appeals generally.7 Rather, jurisdiction must be expressly granted by statute. This Comment considers under what statute, and on what grounds, federal circuit courts may hear appeals of § 3582(c)(2) motions. This issue matters for the tens of thousands of defendants who became eligible for sentence reduction under Amendment 782 and the many more affected by previous retroactive amendments.8

The circuits debate which of two jurisdictional statutes controls appealability of § 3582(c)(2) motions. The first, 28 USC § 1291, is a general grant of jurisdiction over “final decisions of the district courts.” By contrast, 18 USC § 3742 is a specific grant of jurisdiction over only “otherwise final sentence[s].” Section 3742 gives appellate courts jurisdiction over just four grounds of appeal: sentences (1) “imposed in violation of the law,” (2) “imposed as a result of an incorrect application of the sentencing guidelines,” (3) “greater than the sentence specified in the applicable guideline range,” or (4) that are “plainly unreasonable” in the case of an offense for which there is no sentencing guideline. For clarity, this Comment often refers to § 1291 as the general jurisdictional statute and to § 3742 as the sentencing jurisdictional statute. Both of these appellate jurisdictional statutes are distinct from § 3582(c)(2), the statute under which trial judges may modify sentences pursuant to a retroactive Guidelines amendment.

Some circuits hold that the jurisdictional statutes coexist, working in tandem such that § 3582(c)(2) proceedings are appealable under either statute.9 Other circuits hold that the jurisdictional statutes are mutually exclusive: only one can apply at a time, and the sentencing statute squeezes the general statute out of the sentencing space.10 The difference matters to criminal defendants. Under the coexistence view, all sentences are appealable. But under the mutual exclusion view, some sentences simply are not appealable—specifically, those sentences that don’t fit within one of the § 3742 categories.11 In those cases, even if the sentencing judge has made an unfair decision or an incorrect factual determination, the defendant cannot obtain relief from a higher court.

In Part I, this Comment describes the legal backdrop against which the circuit split has unfolded—the circumstances in which § 3582(c)(2) motions may be filed and granted; the relevant jurisdictional statutes; and the Supreme Court’s three landmark sentencing decisions: United States v Booker,12 Gall v United States,13 and Dillon v United States.14

In Part II, this Comment addresses the circuits’ varied decisions and rationales on § 3582(c)(2) motion appealability. The Sixth Circuit was the first to consider seriously the extent of its appellate jurisdiction over these motions. That court held that it could hear only appeals of § 3582(c)(2) motions that fell within one of the sentencing jurisdictional statute’s four categories.15 However, most other circuits have favored the view that the two jurisdictional statutes coexist in the sentencing context: any sentence not appealable under the sentencing jurisdictional statute is appealable under the general jurisdictional statute.16 Still, the circuits have reached this conclusion through differing reasoning.17 As the diverse results and reasoning suggest, strong arguments are available on both sides of the circuit split.

In Part III, this Comment proposes a novel solution with two core insights. First, this Comment proposes allowing appeals of the eligibility determination step under § 1291 (the general jurisdictional statute) given that it does not impose a new sentence in any case the defendant will appeal. Second, this Comment proposes allowing appeals of the discretionary reduction step under § 3742 (the sentencing statute) because either reimposition of the original sentence (now an upward departure) or imposition of a lowered sentence (now within the Guideline range) is an “otherwise final sentence” and thus falls within the zone of § 3742’s applicability.

I. Legal Backdrop: Sentence Modification, Jurisdictional Statutes, and Supreme Court Precedents

Congress created the Sentencing Guidelines as part of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984.18 The Guidelines were designed to reduce unfair disparities between sentences imposed for similar crimes.19 To that end, they created a grid of offense levels, with each offense level correlated to a sentence range.20 Each crime has a base offense level, and specified aggravating or mitigating factors raise or lower the offense level from that starting point.21 Once the offense level has been determined, it is combined with a specified criminal history category to produce a range of sentences (Guideline range).22 As originally created, the Guidelines were binding: except in rare circumstances, judges were required to impose a sentence within the Guideline range.23 But that changed in 2005 when the Supreme Court held that the Guidelines were unconstitutional as a mandatory regime but could continue to exist as an advisory regime.24 Thus, courts today calculate the Guideline range but may impose a sentence within, above, or below that range.

The Sentencing Reform Act also created the United States Sentencing Commission, an independent agency tasked with researching and reporting to Congress on the effectiveness of the Guidelines and other sentencing issues.25 Most pertinent to this Comment, the Sentencing Commission has statutory authority to promulgate26 and amend27 the Guidelines. Amendments that are designated as retroactive permit defendants to move for sentence reduction in light of the new Guidelines.28 This Comment considers the appealability of such motions.

The circuit split over the appealability of motions for sentence reduction pursuant to retroactive Guidelines reduction under 18 USC § 3582(c)(2) has developed in the shadow of an analogous body of law governing sentence reductions under the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, the interaction of two jurisdictional statutes, and three landmark Supreme Court decisions. Part I.A explores the mechanics of § 3582(c)(2) motions, including the effects of the policy statement in Sentencing Guidelines § 1B1.10 and the factors 18 USC § 3553 instructs judges to consider in sentencing. Part I.B explains the two jurisdictional statutes at issue, 28 USC § 1291 and 18 USC § 3742(a). Part I.C surveys the three Supreme Court cases that have set the outer limits on possible interpretations of the statutes.

A. Motions for Sentence Reduction under 18 USC § 3582(c)(2)

Motions under § 3582(c)(2) permit, but do not require, sentence modification after the applicable Guideline range “has subsequently been lowered by the Sentencing Commission.”29 When a defendant is eligible for a sentence reduction under § 3582(c)(2), the court has discretion over whether to grant the reduction based on consideration of two sources: the factors in 18 USC § 3553(a) and “applicable policy statements issued by the Sentencing Commission.”30 This Section discusses both the § 3553(a) factors and the relevant policy statement, § 1B1.10.

As background, § 3553(a) instructs the sentencing judge, whether imposing a sentence immediately after conviction (the plenary sentencing context) or in a postconviction context like a § 3582(c)(2) motion, to consider several factors. Judges should consider the retributive, deterrent, rehabilitative, and incapacitative goals of criminal sentencing.31 They should also consider the nature and circumstances of the offense, the defendant’s history and characteristics, the sentences available, Sentencing Commission policy statements, consistency with similarly situated defendants, and restitution to victims.32 As enacted, the statute next required that judges use these factors to issue a sentence within the Guideline range except in rare, defined circumstances.33 However, that part of the statute was excised in 2005 in Booker.34 Otherwise, § 3553(a) remains good law and continues to guide judges in their sentencing decisions. Indeed, sentences that fail to consider the § 3553(a) factors can be vacated.35

In addition to considering the § 3553(a) factors, judges deciding a § 3582(c)(2) motion must also consider USSG § 1B1.10, the applicable policy statement. The policy statement details a series of requirements for sentence reduction eligibility. First, the Guideline under which the defendant was sentenced must have been amended since the time of sentencing.36

The amendment must be also retroactive.37 Qualifying amendments are listed in § 1B1.10(d). These amendments include, for example, modifications to firearm enhancements,38 correcting a typographical error in a drug quantity table,39 and changing how oxycodone quantities are measured.40 Each of these retroactive amendments has two effects. Prospectively, it lowers the Guidelines range (and thus the likely sentence) for defendants sentenced in the future. Retrospectively, it entitles defendants sentenced under the previous Guidelines to file a § 3582(c)(2) motion for sentence modification.

Additionally, the amendment must result in a lower Guideline range for the particular defendant.41 This requirement is met easily in most cases but becomes important in a few factual scenarios. For example, a statutory mandatory minimum sentence can operate independently from the Guidelines to prevent a Guideline-level reduction from resulting in a lower sentence.42 This prevents eligibility for § 3582(c)(2) motion reduction because the defendant is sentenced under the statutory mandatory minimum, not under the Guideline; thus, lowering the Guideline range doesn’t affect the sentence, so it doesn’t make sense to reconsider the sentence after an amendment.43 But the requirement is not limited to mandatory minimums. Guidelines adjustments also may be offset, with an amendment lowering the sentence for one element of a defendant’s offense while raising it for another. This also makes the defendant ineligible for a sentence reduction.44

Finally, the sentencing judge must correctly calculate the applicable range under the amended Guideline. The policy statement limits the extent of reduction permissible: the court may not reduce the sentence to one below the amended Guideline range, nor may it reduce the sentence to less than the time the defendant has already served.45

A few developments from the Supreme Court have impacted the meaning and application of the policy statement. Although Part I.C below addresses these precedents more thoroughly, I highlight two here. First, the policy statement notes (as the Supreme Court has held46 ) that it is unaffected by Booker, meaning that it “remains binding on courts in [§ 3582(c)(2)] proceedings.”47 Because the text of § 3582(c)(2) permits sentence reductions only when permitted by the policy statement, the policy statement has the “special status” (unusual for elements of the Guidelines) of binding law.48 This is true even after Booker rendered the Guidelines discretionary, as the Supreme Court recently confirmed.49

Second, the Court has impacted the lower courts’ consideration of § 3582(c)(2) motions by dividing them into two steps. At Step One, the court must decide whether the defendant is eligible for a sentence reduction under the § 1B1.10 policy statement.50 At Step Two, if the defendant is eligible, the court weighs the § 3553(a) factors to determine whether, in its discretion, the defendant’s sentence should be modified.51 In some circuits, courts may also consider postsentencing conduct.52

* * *

Note that these precedents combine with the policy statement to produce exactly three possible outcomes for defendants who have filed § 3582(c)(2) motions. First, a defendant may be found ineligible for a sentence reduction because he or she fails to meet one of the requirements in § 1B1.10. In this first set of cases, the defendant’s sentence remains unchanged. Second, a defendant may be found eligible and receive a new sentence. In this second set of cases, because the Guidelines remain mandatory in § 3582(c)(2) motions, the new sentence must be within the amended Guideline range. There is one exception to this—the third possible outcome: a defendant may be found eligible for a § 3582(c)(2) sentence reduction but denied a downward adjustment at the judge’s discretion. In this third set of cases, the defendant keeps his old sentence even though it is now higher than the otherwise mandatory amended Guideline range.53

B. The Jurisdictional Statutes

The circuits considering the issue have identified two possible sources of appellate jurisdiction over § 3582(c)(2) motions: 28 USC § 1291 and 18 USC § 3742. This Section discusses each statute and when it applies.

Section 1291 is a general grant of appellate jurisdiction over “all final decisions of the district courts.”54 Cited in over 93,000 cases on Westlaw as of this writing, it is the bedrock jurisdictional statute of the federal courts of appeals. Thus, the primary and baseline requirement for appealability of district court decisions is finality. This embodies the familiar congressional policy against interrupting judicial proceedings with piecemeal interlocutory review.55 Identifying a typical § 1291 case is impossible: as the workhorse of the courts of appeals, the typical § 1291 case is the typical appeal.

The other relevant jurisdictional statute, § 3742, is narrower in two dimensions: it applies to fewer cases and permits appeal in fewer cases to which it applies. Specifically, it applies to “otherwise final sentence[s]” and permits appeal only when the defendant challenges the sentence in one of four ways.56 The courts have jurisdiction to hear only appeals arguing that a sentence (1) “was imposed in violation of law,” (2) was imposed through “an incorrect application of the sentencing guidelines,” (3) is “greater than the sentence specified in the applicable guideline range,” or (4) “was imposed for an offense for which there is no sentencing guideline and is plainly unreasonable.”57 On its face, the statute makes clear that “otherwise final sentences” are not appealable for reasons other than these four. This plain reading is backed up by the statute’s stated purpose: establishing “a limited practice of appellate review of sentences in the Federal criminal justice system.”58

The typical § 3742 case arises in the plenary sentencing context when a defendant wishes to appeal his sentence at the conclusion of his trial. In this context, he must craft his appeal to fall within one of the four categories of appealable “otherwise final” sentences. Postsentencing modification motions like those made pursuant to § 3582(c)(2) thus constitute only some of the appeals arising under § 3742, but they occur with sufficient frequency to spawn a substantial body of precedent on their appealability.

Which statute governs the appeal matters from the defendant’s perspective: more sentences would be appealable under § 1291 (any sentence) than under § 3742 (only four kinds of alleged mistakes). If courts have jurisdiction over § 3582(c)(2) appeals under § 3742, courts would lack jurisdiction over some motions the defendant wishes to appeal. To see this difference, suppose a defendant wishes to appeal a § 3582(c)(2) motion ruling in which the court has reduced the sentence to one within the Guideline range but on the high end: the defendant would prefer a lower sentence. This case—which may arise with some frequency—does not fit into any of the categories that the sentencing jurisdictional statute makes reviewable: it is not in violation of law, it was (presumably) a correct calculation of the Guidelines, it is within the Guideline range, and there is an applicable Guideline. Presumptively, the only § 3582(c)(2) cases that are appealable under § 3742 are those in which the district court has miscalculated the Guideline range.59

C. The Supreme Court Backdrop

Three Supreme Court decisions constrain available interpretations of the jurisdictional statutes. In Booker, decided in 2005, the Court held that the Sentencing Guidelines were unconstitutional as a mandatory scheme and excised some sections of the statute to reconstitute the Guidelines as an advisory scheme.60 Necessarily, the Court ruled along the way on sentence appealability.61 Two years later, in Gall, the Court explained that reviewing sentences for reasonableness imposes an abuse of discretion standard on appeal.62 In 2010, the Court decided in Dillon that Booker’s Sixth Amendment rationale does not apply to § 3582(c)(2) proceedings because they are not resentencing proceedings.63 Thus, it is permissible for the Sentencing Commission to issue mandates to the district courts in the § 3582(c)(2) motion context. The following paragraphs discuss each decision in further detail.

Booker is best known for rendering the Guidelines unconstitutional as a mandatory scheme,64 but its appellate consequences, detailed in Justice Stephen Breyer’s majority opinion, are more relevant here.65 Breyer’s opinion implemented the merits holding by identifying the specific parts of the sentencing statutes that needed to be excised to render the Guidelines constitutionally compliant. Specifically relevant to this Comment, Breyer wrote that § 3742(e),66 the Guidelines’ standard of appellate review, had to be struck down because it “depend[ed] upon the Guidelines’ mandatory nature.”67 Section 3742(e)’s requirement of de novo review of Guidelines departures and its cross-references to the constitutionally offensive portions of 18 USC § 355368 reflected its dependence on the Guidelines’ mandatory nature.69 De novo review of a now discretionary decision is something of a contradiction in terms. Breyer wrote that the statutory scheme continued to function without § 3742(e)’s standard of review because the remainder of the statute implied that sentences would be reviewed for reasonableness.70 Thus, § 3742 “continues to provide for appeals from sentencing decisions” even after excision of the constitutionally invalid portions.71

Shortly after Booker, the Court clarified in Gall how appellate courts should apply this new reasonableness review. In that case, the Court instructed that “reasonableness” review applied “the familiar abuse-of-discretion standard of review” to sentencing decisions.72 This means that “a district judge must give serious consideration to . . . any departure from the Guidelines and must explain his conclusion . . . with sufficient justifications.”73 The Court identified both procedural and substantive elements of the reasonableness inquiry: the reviewing court must “first ensure that the district court committed no significant procedural error,” like an improper Guidelines calculation.74 Then, the district court must “consider the substantive reasonableness of the sentence,” taking “into account the totality of the circumstances.”75 Abuse of discretion review is appropriate because, compared to appellate courts, district courts are better situated to access evidence about credibility, are more familiar with the facts of the case, and are more familiar with the Guidelines system generally.76

Despite Breyer’s optimism about the surgical precision with which the unconstitutional portions of the Sentencing Reform Act could be severed, Booker has destabilized swaths of criminal procedure. The Supreme Court’s third case in this area, Dillon, addressed that destabilization in the § 3582(c)(2) motion context, holding that USSG § 1B1.10 is still mandatory post-Booker.77 Specifically, the Court considered the portions of § 1B1.10 that prohibit judges from downward departures from the Guideline sentencing range “[e]xcept in limited circumstances.”78 Writing for the Court, Justice Sonia Sotomayor reasoned that this restriction remained permissible because Booker’s Sixth Amendment rationale79 does not apply in the § 3582(c)(2) context.80

This is so, Sotomayor wrote, for two reasons. First, while defendants have a constitutional right “to be tried by a jury and to have every element of an offense proved by the Government beyond a reasonable doubt,” they do not have that same constitutional entitlement to retroactive downward revisions of the Sentencing Guidelines.81 This is especially true now that the Guidelines are advisory: defendants do not have a baseline right to benefit from retroactive amendments to Guidelines the courts did not even have to follow in the first instance. Second, and more significantly for this Comment’s purposes, Booker’s rationale does not apply because § 3582(c)(2) motions are not resentencing proceedings, but rather “modif[ications of] a term of imprisonment.”82 This is how the statute refers to itself, and this language is distinct from descriptions of other sentence modification vehicles.83 Further, the statute’s narrow applicability suggests congressional intent to allow courts to tweak an otherwise final sentence, not create “a plenary resentencing proceeding.”84 Finally, § 3582(c)(2) proceedings are “narrow exception[s] to the rule of finality” of sentences, not sentencing proceedings.85 This is based on the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which require defendants to be present at “sentencing,”86 and expressly do not require defendants to be present at § 3582(c)(2) proceedings.87 Thus, the Court reasoned, they are not sentencing proceedings.88

Dillon’s final important contribution to the legal backdrop is its crystallization of the two-step process for a § 3582(c)(2) motion. Step One is an eligibility determination: “A court must first determine that a reduction is consistent with § 1B1.10” by narrowly recalculating the Guideline range in light of the retroactive amendment prompting the motion.89 At Step Two, the court may reduce the defendant’s sentence, considering “whether the authorized reduction is warranted . . . according to the factors set forth in § 3553(a).”90 Sotomayor concluded that “[f]ollowing this two-step approach” does not yield a new sentence “in the usual sense”91 —language that would soon divide the courts of appeals.92

In sum, the Supreme Court has significantly changed the sentencing landscape. It first rendered the Guidelines advisory, which meant (among other things) replacing the de novo standard of appellate review with review for reasonableness. It next explained what reasonableness review means—considering both the reasonableness of the procedure and of the outcome. Finally, it explained that these changes from the statutory scheme do not apply to courts hearing § 3582(c)(2) motions because such proceedings lack the same constitutional necessity as plenary sentencing proceedings. But as the next Part explains, the courts of appeals have struggled to implement this intricate doctrine in practice.

II. The Circuits’ Approaches to Appellate Review of § 3582(c)(2) Motions

Since Booker transformed the Sentencing Guidelines into a discretionary scheme, the circuits have disagreed on the reviewability of § 3582(c)(2) motions for sentence modification after retroactive downward Guidelines revisions. The two candidates for jurisdiction are 28 USC § 1291, a general grant of jurisdiction over “final decisions of the district courts,” and 18 USC § 3742, a limited grant of jurisdiction over “otherwise final sentence[s].” Some courts have found jurisdiction only under § 3742 (which this Comment refers to as the sentencing jurisdictional statute), others only under § 1291 (which this Comment refers to as the general jurisdictional statute), and others under either.

Broadly, the circuits diverge on how they conceptualize the statutes’ interaction. The first view is that the statutes are mutually exclusive: if one operates in a domain, the other is squeezed out. That is, under this view, § 1291’s general grant of appeal is unavailable for appeals of “otherwise final sentences,” § 3742’s domain. The mutual exclusion view thus requires a determination of what § 3582(c)(2) proceedings are. Are they sentencing proceedings within the narrow zone in which § 3742 controls? Or are they generic postsentencing motions, unrelated to sentencing, within the broader sphere in which § 1291 controls?93 Under this mutual exclusion view, if § 3582(c)(2) motions are within the zone § 3742 controls, only those appeals that fit within the § 3742 categories are appealable; courts of appeals lack jurisdiction to review all other kinds of errors.

The second view is that the two jurisdictional statutes coexist within the same domain; that is, a sentence is appealable under § 3742’s grant of jurisdiction over sentencing appeals if it falls within the four categories specified by that provision and appealable under the general statute if it does not. The statutes work in tandem and occupy the same domains. Under this coexistence view, there is never a case in which the courts lack jurisdiction over a final criminal sentencing decision. Thus, § 3582(c)(2) motions would always be appealable, regardless of whether they are “sentencing decisions.”

The circuits’ sorting into these two views of the statutes’ interaction is driven by their treatment of four difficulties: superfluity, implied repeal, whether the § 3582(c)(2) proceeding is a sentencing, and the meaning of reasonableness review. First, the superfluity issue is a critique of the coexistence view: if the general jurisdictional statute permits an appeal in every sentencing case that falls outside the sentencing appeals statute’s narrow categories of appealability, isn’t the sentencing appeals statute superfluous?94 Second, by contrast, the implied repeal issue is a critique of the mutual exclusion view: if no sentences outside the four categories may be appealed, then the sentencing appeals statute has implicitly repealed part of the general jurisdictional statute—but implied repeals, especially partial implied repeals and especially of bedrock jurisdictional statutes, are disfavored.95 Third, the question whether the § 3582(c)(2) proceeding is a sentencing springs from the Court’s statement in Dillon that such proceedings do not impose a new sentence “in the usual sense.”96 If § 3582(c)(2) proceedings are simply generic posttrial proceedings (and not sentencings at all), then the sentencing appeals statute is irrelevant regardless of whether § 1291 and § 3742 are mutually exclusive or coexist; all § 3582(c)(2) motion rulings are appealable. Fourth, the reasonableness review issue is similarly antecedent. Some courts have read Booker to create appellate jurisdiction to review all sentences for reasonableness, rendering the dispute about the statutes irrelevant.97 If this is correct, all § 3582(c)(2) motions are appealable—not because of a reading of the statutes but because of Booker.

The following discussion highlights how these questions drive the circuits’ disagreement.

A. Mutual Exclusion: The Sixth Circuit

The Sixth Circuit ignited the controversy when it raised the question of jurisdiction in United States v Bowers.98 Before Bowers, appellate courts had made cursory references to jurisdiction when considering appeals of § 3582(c)(2) motions, but no court had carefully considered the question.99 But after Bowers, as the rest of this Section discusses, the circuits began to weigh in with their own analyses.

The facts of Bowers are relatively typical of the cases at issue. Bowers pleaded guilty to powder and crack cocaine distribution charges.100 His Guideline range was 360 months to life, but he pleaded guilty for a sentence of 120 months.101 After he breached the plea agreement prior to sentencing, the court sentenced him to 262 months.102 The government filed a motion under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 35(b) for sentence reduction based on postsentencing investigative assistance.103 Bowers filed his § 3582(c)(2) motion, based on an unrelated retroactive Guideline amendment, shortly thereafter.104 The court denied any sentence reduction under either motion because Bowers had assaulted another inmate while the motions were pending.105 Bowers appealed on two grounds. First, he argued that the court erred factually in its determination that he had assaulted another prisoner.106 Second, he argued that the sentence reduction denial was unreasonable.107 To rule on these questions, the Sixth Circuit looked to its precedent—and the underlying circuit split that precedent implicated—on analogous motions for postsentencing leniency under Rule 35(b). Because several other circuits also consider Rule 35(b) precedents in their § 3582(c)(2) rulings, the following Section briefly recaps the Rule 35(b) circuit split before turning to its impact on the Bowers court’s reasoning.

1. The analogous, underlying Rule 35(b) circuit split.

In a nutshell, Rule 35(b) permits sentence reduction for defendants who cooperate with government investigations after sentencing.108 Although Rule 35(b) is a distinct procedural vehicle from § 3582(c)(2), courts draw a sensible analogy between them: the same jurisdictional statutes, §§ 3742 and 1291, determine appealability for both vehicles, and, according to Dillon, neither a Rule 35(b) motion nor a § 3582(c)(2) motion constitutes a sentencing.109 Unsurprisingly, then, a similar circuit split has emerged over Rule 35(b) motions.

In the first case forming the circuit split, United States v McAndrews,110 the First Circuit adopted the mutual exclusion view and then held that Rule 35(b) motions are appealable only under 28 USC § 1291.111 The First Circuit reasoned that, before § 3742 was enacted, courts had had jurisdiction over sentencing appeals under § 1291 because sentencing constitutes a “final decision[ ]” of a district court.112 But Congress changed the landscape when it enacted 18 USC § 3742 as the “exclusive avenue” for appealing criminal sentences.113 As a result, the court concluded that “only sentences that meet the criteria limned in section 3742” are appealable.114 Because the motion clearly did not fall into any category of appeal under § 3742, it appeared that the defendant was out of luck. Still, the McAndrews court held that it had appellate jurisdiction over Rule 35(b) motions under § 1291 notwithstanding the existence of § 3742 because an order resolving a Rule 35(b) motion “is not, properly speaking, a sentence.”115 Rather, like most other postjudgment motions, its appealability stems from § 1291.116

Every other circuit to consider the question has rejected this reasoning.117 The Eleventh Circuit was the first to do so. In United States v Yesil,118 the court took jurisdiction over a Rule 35(b) appeal under § 3742.119 This move required concluding that Rule 35(b) proceedings are sentencing proceedings, not generic postjudgment motions; otherwise, jurisdiction under § 3742 would not be appropriate. Even the dissent assumed that a Rule 35(b) order constitutes a resentencing.120

2. The Bowers court’s reasoning.

In Bowers, the Sixth Circuit adopted the mutual exclusion view to hold that it had jurisdiction over the defendant’s § 3582(c)(2) motion only under the sentencing jurisdictional statute, if at all. Because it considered the statutes mutually exclusive,121 the question reduced to whether the appeal was of the ruling on the sentence reduction motion (in which case the general grant of jurisdiction in § 1291 is available) or the sentence resulting from the motion (in which case only the narrow grant of jurisdiction in § 3742(a) is available).122 This Section explains how the court reached its conclusion by drawing an analogy to Rule 35(b) motions and carefully parsing the Supreme Court’s decision in Dillon.

In-circuit precedent treated Rule 35(b) motions as “effectively impos[ing] a new sentence,” so they were appealable only under § 3742.123 The court concluded that § 3582(c)(2) motions are indistinguishable from Rule 35(b) motions in all relevant aspects.124 This was because both permit “discretionary reduction . . . of an already imposed sentence.”125 Both motions permit discretionary postsentencing leniency, so defendants appealing § 3582(c)(2) rulings are appealing their sentences, not the denial of the motion itself.126 Thus, the court reasoned, § 3582(c)(2) motions also effectively impose a new sentence.

The court recognized one difference between the motions, though: the Supreme Court’s decision in Dillon applied to § 3582(c)(2) motions but not to Rule 35(b) motions. To conclude that appeals of § 3582(c)(2) motions fall within the sentencing appeals statute, the court thus needed to grapple with Dillon’s statement that a § 3582(c)(2) decision does not impose a new sentence “in the usual sense.”127 It reconciled its conclusion with this language by noting that Dillon had just defined the proceeding as a two-step inquiry. As the Sixth Circuit saw it, the Court was merely observing that the § 3582(c)(2) decision was thus procedurally unlike a plenary sentencing, not commenting that “the end result of a sentence-reduction proceeding is not a ‘sentence’ within the meaning of § 3742.”128 Supporting this reading, the Dillon Court elsewhere referred to § 3582(c)(2) proceedings as an exception to the general rule that sentences are final once imposed.129 Given this inconsistency, the Sixth Circuit expressed doubt that the Supreme Court intended to radically alter the appealability of § 3582(c)(2) proceedings “with a single passing comment.”130 The Bowers court concluded that, Dillon’s at-first-glance contradictory language notwithstanding, § 3582(c)(2) motions are sentencings and thus appealable only under § 3742.131

Having determined that jurisdiction was available only under the sentencing jurisdictional statute, if at all, the court proceeded to determine whether Bowers’s appeal fell within one of that statute’s four categories. Because the appeal didn’t obviously fall within one of the categories, the court considered whether review for reasonableness could fit within § 3742(a)(1) (imposed “in violation of law”).132

The Sixth Circuit’s precedents seemed to point in opposite directions. In the plenary sentencing context, every circuit treated the new reasonableness review as falling within the “imposed in violation of law” category of § 3742(a).133 But the Sixth Circuit had reached the opposite result in the Rule 35(b) context, reasoning that Booker had left § 3742’s jurisdictional scope untouched.134 Despite the clear conflict, the Sixth Circuit did not attempt to reconcile its Rule 35(b) determination with the contradictory reasoning in the plenary sentencing context.135 Thus, the court was left to wrestle with which precedent should control the appealability of § 3582(c)(2) motions.

The court turned to Dillon for a resolution. It concluded that Dillon (which addressed § 3582(c)(2) motions specifically) answered this question clearly: Booker’s remedial opinion—including the creation of reasonableness review—does not apply to proceedings under § 3582(c)(2).136 Thus, the court concluded, reasonableness review is not available in the § 3582(c)(2) context.137 Because such review was unavailable, Bowers’s only possible § 3742 avenue for appeal, “imposed in violation of law,” was closed.138

The Sixth Circuit remains the only circuit to have found jurisdiction exclusively in § 3742 in a precedential opinion although another circuit has indicated agreement with the Bowers court’s position.139

B. The Response: Circuits Finding Coexistence

After the Sixth Circuit raised the jurisdictional question, other circuits began weighing in. Each circuit to disagree with the Bowers court has held that its decision was compelled by precedent. These determinative precedents, however, have little reasoning in common, as the following discussion demonstrates. The disagreements highlighted already—about superfluity, implied repeal, the nature of § 3582(c)(2) proceedings, and the meaning of reasonableness review that the Booker Court created—drive the circuits’ divergent reasoning. Not every circuit addresses each issue, and the circuits assign different weights to the arguments. This leads to roughly three different outcomes. One pair of circuits concludes that reasonableness review is the deciding factor. One circuit weighs the risk of rendering the sentencing jurisdictional statute superfluous against the difficulty of finding that Congress has implicitly repealed a bedrock jurisdictional statute, finding the latter consideration stronger. A final circuit resolves the jurisdictional question by concluding that § 3582(c)(2) motions are not sentencings at all. The following Sections describe the courts’ reasoning supporting these conclusions.

1. The Ninth and Third Circuits: reasonableness review is determinative.

The Ninth Circuit rejected the Bowers court’s reasoning in United States v Dunn140 and permitted review for reasonableness of § 3582(c)(2) motions under the general jurisdictional statute, § 1291.141 The court offered two rationales to reconcile this position with the Supreme Court’s statement in Dillon that Booker’s reasonableness review does not apply to § 3582(c)(2) proceedings.142 First, Dillon did not directly address reasonableness review; rather, it addressed USSG § 1B1.10, the policy statement governing § 3582(c)(2) proceedings.143 The Ninth Circuit thus agreed with the Sixth Circuit that Dillon only concerned the first step of § 3582(c)(2) proceedings, which determines whether the defendant is eligible for sentence reduction.144 Because Dunn considered Step Two while Dillon considered Step One, the decisions were consistent.145 Second, the court concluded that no Supreme Court precedent limited reasonableness review to Step One determinations.146 Thus, the Ninth Circuit concluded that reasonableness review is available for Step Two of a § 3582(c)(2) proceeding in an appeal under § 1291.

In its own brief opinion on the circuit split, the Third Circuit reached a similar result, concluding first that it had jurisdiction under § 1291 and second that § 3742 did not act to obstruct that jurisdiction.147 Section 3742, it reasoned, did not bar jurisdiction under the general appeals statute because § 3742 permits reasonableness review: “an unreasonable sentence is ‘imposed in violation of law’ under 18 U.S.C. § 3742(a)(1).”148 The court believed that this meant that the jurisdictional statutes do not conflict and indeed work in tandem with each other.149

2. The Tenth Circuit: implied repeal trumps superfluity.

The Tenth Circuit rejected the Bowers court’s approach in United States v Washington.150 Although both courts considered arguments about implied repeal and superfluity, the Washington court reached the opposite outcome because of its assessment of their relative strengths. Because of a complex procedural history,151 the court considered the unusual question of whether the sentencing court erred in calculating the quantity of drugs on which it based the defendant’s sentence.152 In earlier decisions, the court had already adopted the view that, in the plenary sentencing context, the sentencing appeals statute and the general appeals statute work in tandem: § 3742 does not displace § 1291.153

In an earlier decision, United States v Hahn,154 the court concluded that the sentencing court’s entry of a sentence constitutes a final order.155 The defendant has the right to appeal under § 1291 or § 3742(a).156 The court acknowledged a problem with this reading: permitting both statutes to operate within the same field renders § 3742’s limitations on appeal superfluous. That is, § 3742 limits appeals by design; if it can be entirely circumvented by permitting appeal under the general statute in all cases in which it would prevent appeal, it lacks any meaning. Because courts try to read statutes to avoid making one or the other superfluous, this is a blow to the Tenth Circuit’s reasoning.

Still, the court reasoned that the generally valid presumption against superfluity was superseded here by a countervailing principle: the disfavor of repeals by implication. That principle precludes repeals by implication except “where provisions in two statutes are in irreconcilable conflict, or where the latter act covers the whole subject of the earlier one and is clearly intended as a substitute.”157 Here, the factors counsel against an implied repeal: the text of the statute suggests no intent to limit § 1291, Congress did not use the “blunt language” elsewhere characteristic of a limit on jurisdiction, and the rule against implied repeal is “particularly persuasive” in the context of bedrock jurisdictional statutes like § 1291.158 Text aside, § 3472’s legislative history does not mention its impact, if any, on § 1291.159 To the contrary, the court deduced that it manifested a congressional intent to expand availability of sentencing appeals.160 Thus, neither text nor history suggests an irreconcilable conflict between the statutes.

3. The DC Circuit: § 3582(c)(2) proceedings are not sentencings.

The DC Circuit’s contribution to the circuit split, United States v Jones,161 also concluded that appellate courts have jurisdiction over § 3582(c)(2) motions under either statute; but unlike the other circuits, the DC Circuit concluded that Dillon required the conclusion that § 3582(c)(2) motions are not sentencings at all.

Jones is the paradigmatic § 3582(c)(2) case: the defendants were convicted on drug trafficking and conspiracy charges, sentenced under Guidelines that were later retroactively adjusted downward, and denied sentence reduction despite eligibility.162 The defendants appealed this denial as unreasonable.163

Before Booker, the DC Circuit had held that the jurisdictional statutes were mutually exclusive.164 However, after Booker “radically changed the landscape,” the court held instead that § 3742 permits review for reasonableness of any sentence.165 This holding, it explained, was “[c]ongruent with if not absolutely compelled by Booker.”166 Thus, based on post-Booker precedent, the court had jurisdiction over the § 3582(c)(2) appeal under § 3742(a) as modified by Booker to permit reasonableness review.

But, the court wondered, did the sentencing jurisdictional statute even apply to § 3582(c)(2) motions—are they sentencing proceedings at all?167 This doubt was based on Dillon’s language that § 3582(c)(2) proceedings “do[ ] not impose a new sentence in the usual sense.”168 Recall that Dillon suggests that Rule 35(b) motions, too, may not be sentencings; the DC Circuit had reached that conclusion independently.169 The court’s conclusion that § 3582(c)(2) motions do not fall within § 3742 because they are not sentencings was strengthened by the fact that the district court had denied the sentence reduction motions; these rulings were “not new sentences by any definition.”170 Thus, regardless of whether it would have jurisdiction under § 3742, the court took jurisdiction under § 1291.

C. Nonprecedential Hints: The Second, Fourth, Seventh, and Eighth Circuits

Four circuits have indicated a position on the circuit split in opinions that are either not reasoned or nonprecedential. Three of these circuits appear to favor the coexistence view. In published opinions that do not acknowledge the circuit split, the Seventh and Eighth Circuits have found jurisdiction sub silentio under § 1291.171 It is possible that these circuits have simply missed the existence of the circuit split.

The Second Circuit reached the same conclusion but has taken the opposite approach—issuing an unpublished but reasoned opinion acknowledging and weighing in on the circuit split. In United States v Nugent,172 the court reasoned that its position was decided by precedent holding that the district courts have jurisdiction over § 3582(c)(2) motions under the general federal question statute, 28 USC § 1331, which—according to the court—suggests that appeal of final judgment would occur under the general appeal statute.173 The court rejected as contradictory to its precedents the government’s attempt to distinguish between appeals of § 3582(c)(2)’s Step One eligibility prong, which it argued are appealable under § 1291, and appeals of the Step Two discretionary reduction prong, which it argued are appealable under § 3742.174

By contrast, the Fourth Circuit has not issued a precedential opinion acknowledging the circuit split, but it has agreed with Bowers’s mutual exclusion reasoning and result in an unpublished order175 and appears bound by precedent to reach this result.176 It is bound by precedent because a pre-Booker case held that § 3742 governs motions under § 3582(c)(2).177

III. The Solution: Two-Step Structure Drives Appealability

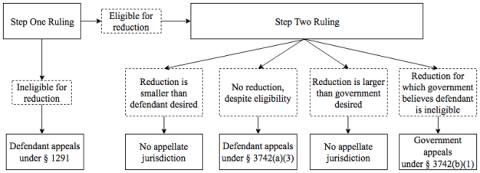

This Part discusses the interpretive problems presented by the interaction of the two relevant jurisdictional statutes and the Supreme Court’s precedents in both the plenary and post-conviction sentencing contexts. As Part II explored, the circuits are deeply split over this issue, with their disagreement driven by arguments about superfluity, implied repeal, the nature of § 3582(c)(2) proceedings, and the meaning of the reasonableness review the Booker Court created. While the treatment of these issues in Part II was limited to arguments that courts have considered, this Part considers other arguments as well. Parts III.A and III.B propose a novel solution based on Dillon: Step One of a § 3582(c)(2) proceeding, the eligibility determination, is reviewable under § 1291, the general statute, while Step Two, the discretionary reduction, is reviewable under § 3742, the sentencing statute. Part III.C then considers the scope and impact of this solution, tied as it is to the § 3582(c)(2) vehicle, on precedent in the plenary and Rule 35(b) sentencing contexts. The following flowchart illustrates how this solution fits into the § 3582(c)(2) process and is referenced throughout the following Sections.178

Figure 1: Flowchart of proposed solution

The flowchart captures when appeals are desired by and available to each party. At Step One, the court determines whether the defendant is eligible for a reduction. If found ineligible, the defendant would likely wish to appeal. This Comment argues that such an appeal is possible under § 1291. If the defendant is found eligible, the government would likely wish to appeal. But because the court immediately proceeds to Step Two, there is no instance in which the government would have occasion to appeal only the Step One ruling, as it is not a final ruling.

At Step Two, the flowchart identifies four possible outcomes. The defendant would likely wish to appeal in two circumstances: if he receives a smaller reduction than desired179 or if he receives no reduction. This Comment argues that appeal is foreclosed in the first circumstance but proposes a novel ground for permitting appeal in the second.

The government would also likely wish to appeal in two circumstances: if the defendant receives a larger reduction than the government desired180 or if he receives a reduction for which the government believes he is ineligible. This Comment argues that, as with defendants, the first outcome is nonappealable, while the second is appealable.

A. Section 3582(c)(2) Step One Is Appealable under § 1291

The first part of the solution is to permit appeals of Step One, the eligibility determination, under § 1291. This makes sense because, as the flowchart illustrates, a denied § 3582(c)(2) motion does not impose a new sentence. Because it is simply a refusal to change an existing sentence, it does not implicate the sentencing jurisdiction statute. If the motion were granted, the court would proceed to Step Two, and the government would thus appeal only after the Step Two determination (that is, when a final decision is rendered).181

Under this approach, defendants can appeal every Step One denial of eligibility for a § 3582(c)(2) reduction, while the government can never appeal just the Step One ruling. This makes sense practically: on the defendant’s side, the eligibility determination is based on facts like those necessary to calculate the relevant Guideline range. Because the Step One determination is factual, errors at that stage are more likely to be corrected on appeal than discretionary sentencing decisions at Step Two. It also makes sense for the government, which may choose not to appeal at all if the defendant is found eligible but still denied any reduction.

This recommendation springs from two sources. First, it was proposed in the related circuit split over Rule 35(b) motions,182 which this Part will discuss in more depth below. Second, it was the government’s argument in Nugent.183 The Second Circuit rejected the argument in a nonprecedential order because it considered itself bound by circuit precedent and refused to distinguish between the two steps of the § 3582(c)(2) determination.184 Despite this rejection, the argument is worth reviving because it has analytic strength and potential to resolve the statutory interpretation tangle at the heart of this circuit split.

The argument’s origin in the Rule 35(b) context bears explaining. The argument that a denied sentence modification motion does not impose a new sentence was forwarded in a nascent form in United States v McDowell.185 There, the Seventh Circuit held that jurisdiction over appeals of granted Rule 35(b) motions was available only under § 3742.186 It reasoned that a granted Rule 35(b) motion clearly imposed a new sentence and reserved the question of whether a denied motion also imposed a new sentence. This insight—that grant and denial of Rule 35(b) motions might lead to asymmetrical appealability—seems odd at first glance but is a sensible reading of the jurisdictional statutes. And it can be easily imported from the Rule 35(b) context to the § 3582(c)(2) motion context given the vehicles’ similarities. In the § 3582(c)(2) context, this insight is consistent with the text of the sentencing jurisdiction statute: because denial of a § 3582(c)(2) motion does not affect the movant’s sentence, a denial is not a sentencing. Therefore, it does not fall within § 3742’s domain—sentencing—and is thus governed by the general appeals statute. Indeed, permitting appeal of a denied § 3582(c)(2) motion as a sentencing appeal amounts to a second bite of the apple: the plenary sentence would be appealable in the first instance and after § 3582(c)(2) motion denial.

This solution is attractive because it makes sense of what would otherwise be internal contradictions in Dillon. This is the Bowers court’s insight: Dillon states, in the middle of its discussion of Step One, that § 3582(c)(2) motion proceedings “do[ ] not impose a new sentence in the usual sense.”187 However, the opinion elsewhere refers to § 3582(c)(2) proceedings as an “exception to the general rule of [a sentence’s] finality.”188 Bowers also notes that the Dillon Court further referred to the district judge’s ruling on the § 3582(c)(2) motion as “the imposition of a sentence.”189 Thus, the Bowers court read Dillon as holding not that the result of a § 3582(c)(2) motion is not a sentence, but rather that the bifurcated process of deciding a § 3582(c)(2) motion is procedurally unlike a plenary sentencing.190 This reading is viable and makes sense of what are otherwise contrary statements within Dillon.

However, this reading is not the immediately intuitive reading of Justice Sotomayor’s words: perhaps it rewrites the phrase from “in the usual sense” to “in the usual manner.” The first reading suggests that modification proceedings are not resentencings at all; the second reading admits they are resentencings, albeit using a different procedure. The availability of the second meaning is not immediately obvious, and the Bowers reading is somewhat strained. However, two considerations redeem the reading despite this defect. First, as the Bowers court explained, the alternative reading takes “a single passing comment” as “drastically expand[ing] the circumstances in which [§ 3582(c)(2)] proceedings are appealable.”191 Second, this is the only reading proposed that reconciles the conflicting portions of the Dillon opinion. No other circuit has advanced another attempt to harmonize the opinion’s internal tensions. Thus, the Bowers court’s reading of Dillon is the best one available and supports the appealability under § 1291 of Step One of § 3582(c)(2) proceedings.

B. Section 3582(c)(2) Step Two Is Appealable under § 3742

The second part of the solution is to permit appeals of the second step of the § 3582(c)(2) determination, the discretionary sentence modification, under § 3742. This makes sense because § 3742 applies to “otherwise final sentences”; and once the defendant has been found eligible in Step One, the sentencing court must make a new sentencing decision. This looks more like an otherwise final sentence than does the denial of eligibility at Step One.192 As Figure 1 illustrates, the defendant would attempt to appeal the Step Two determination only when a sentence is either not reduced at all or is reduced less than desired. The government, on the other hand, would attempt to appeal the Step Two determination when it believes the Step One eligibility determination was incorrect or when it objects to the extent to which the defendant’s sentence was reduced.193

Because § 3742 has received several different constructions in the wake of the Supreme Court’s relevant rulings,194 two questions remain. First, is reasonableness review available? Second, under what prong of § 3742 do Step Two determinations fit? That is, how many sentences are reviewable?

1. Is reasonableness review available?

Circuit court holdings notwithstanding, Dillon unequivocally states that Booker’s Sixth Amendment rationale does not apply in the § 3582(c)(2) motion context.195 If that is the case, the § 3582(c)(2) scheme is not unconstitutional. Sotomayor explained why in Dillon: defendants have a constitutional right to be tried by a jury, but they lack a constitutional entitlement to benefit from postsentencing downward Guidelines adjustments.196 Further, even in the conviction and plenary sentencing context, defendants lack a constitutional right to appeal.197 Any right to appeal comes only from statute. Thus, a defendant’s Sixth Amendment rights are not implicated if he may not appeal the discretionary refusal to modify his sentence in the wake of a retroactive downward Guidelines amendment.

Recall that Booker rendered the Sentencing Guidelines advisory rather than mandatory by holding unconstitutional portions of two statutes: the portion of § 3553 requiring judges to treat the Guidelines as mandatory and the portion of § 3742 setting forth standards of appellate review premised on the Guidelines’ mandatory nature.198 Instead of the original statutory regime, which unconstitutionally required departures from the Guidelines to be reviewed more stringently than sentences falling within the Guidelines, the Court substituted review for reasonableness: Was the sentence reasonable, regardless of whether it fell within the Guideline range?199 Saying that reasonableness review does not apply to § 3582(c)(2) motions thus means that they are reviewed under the otherwise excised statutory section, § 3742(e), governing appellate standards of review.

If Booker’s merits holding does not apply to § 3582(c)(2) proceedings, it’s difficult to see why its holding creating reasonableness review should apply. Still, no court has suggested that § 3742(e) retains any vitality after Booker, in any context. The courts may or may not be wrong to ignore this argument, but their omission at least means that Dillon’s holding that Booker does not apply in the § 3582(c)(2) motion context does not definitively answer the question of whether review for reasonableness is available. Thus, the next paragraphs delve into what reasonableness review looks like in the § 3582(c)(2) motion context.

The courts have produced two versions of reasonableness review in the sentence modification context. One view is jurisdictional: it concludes that Booker blew the jurisdictional doors off their hinges when it instituted review of “all sentences” for reasonableness in its remedial opinion.200 The other view is that Booker did not alter the scope of jurisdiction by instituting reasonableness review but merely replaced the standards of review in the excised § 3742(e) with reasonableness review.201

To see the difference between the views, consider a hypothetical defendant who wishes to appeal his § 3582(c)(2) motion’s Step Two ruling because it reduces his sentence, but not as much as he would prefer. A court taking the first view would ignore the jurisdictional statutes altogether and review the sentence for reasonableness. The Third Circuit takes this approach.202 By contrast, a court taking the second view would first decide whether a jurisdictional statute permits it to hear the appeal and then consider whether the sentence imposed below is reasonable. The Sixth Circuit takes this approach.203

The second view is more defensible because it is, in fact, what the Booker Court said it was doing. In his portion of the majority opinion, Justice Breyer first invalidated § 3742(e), the section stating the standard of review a court applies only once jurisdiction was established under § 3742(a) (appeal by defendant) or § 3742(b) (appeal by the government). He then replaced it with review for reasonableness—which he argued was implicit in the remaining sections of the statute.204 Nowhere did he suggest that he was modifying the number of sentences that would be appealable. The first view of reasonableness review reads the opinion as modifying appellate jurisdiction rather than the standard of review. Instead, Breyer clearly thought he was modifying how already appealable sentences were reviewed.205

Thus, the best reading of Booker and Dillon is that § 3582(c)(2) Step Two determinations are appealable when they fit within one of the prongs of § 3742(a) or (b) and, when appealable, are reviewed for reasonableness.

2. Under what prong of § 3742 are Step Two determinations appealable?

The standard of review of appealable sentences is so much ink on paper unless at least some § 3582(c)(2) determinations fit into one of the § 3742 categories of appealable sentences. The final advantage of splitting the jurisdictional basis of appeal of the two steps of § 3582(c)(2) motions is that Step Two appeals fit into a different prong of § 3742 than courts have previously considered. This Comment proposes that denial of sentence reduction despite eligibility is appealable under § 3742(a)(3) as an upward departure from the Guideline range.206

Thus far, courts that have considered the appealability of § 3582(c)(2) under § 3742 have considered only the possibility of fitting appeals into § 3742(a)(1), appeals of sentences “imposed in violation of law.”207 They have then considered whether an unreasonable sentence can properly be considered to be “in violation of law.”208 This inquiry is simplified by this Comment’s bifurcated approach: as discussed in Part III.B.1, reasonableness is the substantive standard of review and does not determine availability of appellate jurisdiction.

This Comment proposes a new route. Existing approaches shoehorn appealability into § 3742(a)(1). This overlooks the possibility of a denial of sentence reduction despite eligibility under § 3742(a)(3), which permits appeal of upward departures from the Guideline range. As discussed in Part I.A, such a denial despite eligibility amounts to an upward departure from the Guideline range.209 That is the case because the Guidelines amendment has lowered the sentencing range, and that lowered range is now—at least arguably—the one § 3742(a)(3) references. To the best of my knowledge, no court has considered this jurisdictional argument.

The viability of relying on § 3742(a)(3) depends on determining in what sense the Guidelines amendments are retroactive. If they are “retroactive” only to the extent that they entitle a defendant to § 3582(c)(2) proceedings, the theory of appealability under the sentencing appeals statute does not work. Or they may be more fully retroactive, such that they “extend[ ] in scope or effect to a prior time or to conditions that existed or originated in the past.”210 The difference matters for appealability under § 3742(a)(3) because that statute refers to departure from the Guideline range—but which range? The unamended range under which the defendant was first sentenced or the amended range? If Guidelines amendments are fully retroactive, then the amended range should be the reference point. This would make a denial of reduction at Step Two an “upward departure.” In the absence of semantic or structural indications, it is unclear to what extent the amendments are retroactive. Both appear to be viable readings of the text. Because there is no strong textual argument that either reading is foreclosed, we should look to the reading that best untangles the knot of issues (superfluity, implied repeal, the meaning of reasonableness review, and the Dillon opinion’s internal tensions) in this area of law—the fully retroactive reading.

Permitting appeal under § 3742(a)(3) of discretionary denials of sentence reduction makes sense because it makes the appealability of § 3582(c)(2) sentences symmetrical with the appealability of plenary sentencing proceedings, thereby preventing a jurisdictional windfall. Under most of the circuits’ approaches, § 3582(c)(2) sentences are appealable under more circumstances than plenary sentences.211 This seems backwards: it reads Booker as having disrupted postsentencing motions more than its intended target, plenary sentencing. It also entitles defendants to appeal from subsequent leniency they are not entitled to benefit from more often than they are entitled to appeal from constitutionally governed plenary sentencing proceedings. This Comment’s bifurcated approach solves that backwardness by introducing symmetry between plenary and postsentencing motions: the court’s discretion is appealable under the same circumstances (upward departures) in each context. The only leap in reasoning that must be made is that reimposition of the original sentence, which is now above the current (and retroactive) Guideline range, is an upward departure. This is sensible: a truly retroactive amendment alters the Guideline range against which the sentence is measured.

Although it restores symmetry between availability of appeal in plenary and resentencing proceedings, the solution is not perfectly symmetrical with respect to a different dimension: the availability of appeals to defendants and the government. This asymmetry exists at both Step One and Step Two. To see the Step One asymmetry, consider the circumstances in which the government would appeal a § 3582(c)(2) ruling, summarized in Figure 1.212 As the flowchart shows, a defendant can appeal immediately after the Step One ruling if it is unfavorable, while the government cannot because there is no final judgment—the court immediately proceeds to the Step Two ruling. This does not, of course, mean that the government cannot argue that the Step One ruling was incorrect in a subsequent appeal of the § 3582(c)(2) ruling; it can make this argument under § 3742(b)(1), arguing that the modified term of imprisonment imposed in Step One was imposed in violation of law because the defendant was ineligible for the sentence reduction.

Figure 1 illustrates a second asymmetry, this time at Step Two: defendants and the government also have different abilities to appeal Step Two rulings. Section 3742(a)(3) permits defendants to appeal the discretionary denial of sentence reduction at Step Two (after a finding of eligibility at Step One) as an upward departure from the Guideline. The government has no corresponding ability under § 3742(b)(3), the provision granting jurisdiction over government appeals of downward departures. This is a consequence of the asymmetry in the sentencing judge’s options under § 3582(c)(2): the judge may either refuse to modify the sentence (which, as this Comment argues, is now an upward departure from the Guideline) or may reduce the sentence to anywhere within the new Guideline range. Neither the government nor the defendant may appeal a sentence within the new Guideline range unless it independently falls within one of the other § 3742 categories. But the defendant may appeal an upward departure, while the government has no corresponding ability to appeal a downward departure—merely because the sentencing court has no ability to depart downward.213

On the one hand, this asymmetry is not inherently troubling: there are defendant-favoring asymmetries in appealability in the conviction context, like the nonappealability of acquittals, and there is no underlying right to appeal in the sentencing context. On the other hand, this asymmetry is concerning: one of the goals of § 3742 was establishing symmetry in appealability of sentences by the government and defendants.214 Still, legislative intent is at best subservient to plain text; even rejecting that hierarchy, transmuting the intent of the Congress that originally enacted § 3742 through the lens of the Booker remedial opinion’s severability analysis (looking counterfactually to what Congress would have done had it known the mandatory Guidelines scheme was unconstitutional) is a mind-boggling task. To whatever extent legislative intent exists in the first place, any remaining vestiges of the intent of the legislature that enacted § 3742 are tattered at best. Of course, the Court has attempted to extract legislative intent from the remainder of the Guidelines scheme. But, notably, even the intent-driven Booker remedial opinion attempted to engage only with constructed intent (from the statute itself), not with actual intent (reflected in the legislative history). The relationship between actual intent and the counterfactual intent Booker constructs is far from certain even for those to whom legislative intent is important.

C. Scope, Impact, and Advisability

The solution this Comment offers consists of three key moves. First, denials of § 3582(c)(2) eligibility (Step One) are appealable under the general appeals statute: they are not sentencings. Second, the best reading of Booker and Dillon concludes that reasonableness review is not jurisdictional. Third, as a consequence, defendants who are eligible for reduced sentences should use § 3742(a)(3) to appeal discretionary denials of sentence reduction because they are upward departures from the (amended) Guidelines. The remaining questions concern this solution’s scope. To what extent does this approach reshape and disrupt circuits’ current approaches to plenary sentencing? Perhaps the solution’s greatest virtue is its minimal displacement of circuit precedent in that area; most circuits can implement it without overruling their plenary sentencing or Rule 35(b) precedents. Because it springs from Dillon’s holding that Booker does not apply in the § 3582(c)(2) context, the solution is cabined to the § 3582(c)(2) context.215 It also deliberately sidesteps the most controversial and wide-ranging question, the extent to which the two jurisdictional statutes are concurrent.216 However, there are two conflicts with plenary sentencing precedent.

One conflict is with the Tenth Circuit’s approach—the coexistence view—which finds jurisdiction in the plenary sentencing context under either statute.217 In the Tenth Circuit, the plenary-resentencing symmetry argument is forceless. In fact, this Comment’s solution would render appeals less available in the resentencing context than in the plenary sentencing context. This is because defendants may appeal their plenary sentences on any ground under the Tenth Circuit’s precedent, while this Comment proposes limited grounds for appeal of § 3582(c)(2) motions. This may not be absurd as a policy matter: given the choice to allocate judicial resources toward hearing more plenary sentence appeals or more sentence reduction motion appeals, hearing more of the former could be sensible. It would permit courts of appeals to catch errors in every sentencing instead of to review decisions about after-the-fact leniency). The point here, though, is a different one: the Tenth Circuit’s conception of the jurisdictional statutes as coexisting in the plenary context cannot be cabined from reaching their interaction in the § 3582(c)(2) context. Thus, accepting this Comment’s solution would require abandoning the Tenth Circuit’s precedents in the plenary sentencing context.

The other conflict is with the circuits that interpret Booker’s substitution of reasonableness review for § 3742(e)’s standard of review as expanding jurisdiction rather than expanding review in cases in which jurisdiction already exists.218 As discussed above, however, this reading should be rejected for two reasons.219 First, it is inconsistent with what the Booker Court described itself as doing—not changing the scope of jurisdiction, but rather changing what review occurs when jurisdiction to review exists. Second, Booker’s remedial opinion does not reach the § 3582(c)(2) context with which this Comment is concerned, as Dillon expressly clarified.220

In terms of impact, this solution would likely operate to reduce the number of appeals compared to a circuit permitting appeal of all portions of the § 3582(c)(2) motion under § 1291, the generic appeals statute. However, it likely would not reduce the absolute number of successful appeals. Why? There are only two kinds of cases that would have different appealability under the two possibilities.

In the first kind of case, appeals disputing factfinding are permissible under § 1291 but not—at least at first glance—under this Comment’s solution. This is because none of the grounds of appeal under § 3742 appears to embrace appeals based on factfinding. But on a closer look, fact-based objections remain appealable under this Comment’s solution at both Step One and Step Two.

There are three kinds of fact-based objections to § 3582(c)(2) rulings. First, defendants may object to factfinding for the purpose of applying the new Guideline range. This occurred in Washington when the Guidelines amendment drew lines around behavior differently than the Guidelines under which Washington was initially sentenced; when he was sentenced, he possessed well above the minimum quantity of drugs necessary for the relevant Guideline level, so he didn’t contest the factual drug quantity determination at his sentencing hearing.221 But the Guidelines amendment raised the minimum threshold to nearer the quantity he possessed, and he wished to dispute the quantity for the first time in his § 3582(c)(2) motion.222 This sort of fact-based appeal fits within § 3742(a)(2), permitting review of an incorrect Guidelines calculation if the defendant believes it has led to a misapplication of the Guidelines.223 Second, defendants may object to factfinding about postsentencing behavior that results in discretionary denial of any reduction despite eligibility, as with Bowers’ alleged assault of a fellow inmate.224 This sort of factfinding, as already argued, is appealable under § 3742(a)(3).225 Third, the only unreviewable facts thus would be those implicated in the sentencing judge’s discretionary decision about which sentence within the amended Guideline range to impose—any facts relevant to the § 3553(a) analysis, for example. This third category of cases is much smaller than expected given the general unreviewability of factfinding. This appears to be the result mandated by § 3742 because Congress chose to limit appeals of sentencing decisions to the four enumerated categories. Thus, more fact-based appeals remain possible than might initially be supposed.

In the second kind of case, sentences within the Guideline range that are based only on the sentencing court’s discretion are appealable under § 1291 but not under this Comment’s proposed solution. This is likely a large category of cases. It contains those cases in which either party seeks to appeal when there has been no procedural error or questionable factfinding but rather an undesired result of the exercise of discretion. Yet these cases are, by and large, unlikely to succeed on appeal.226 Exercise of sentencing discretion is reviewed deferentially; in the absence of more besides a party’s mere unhappiness with the outcome, courts of appeals are unlikely to have cause to intervene.

These differences highlight why § 3742 makes sense as a policy matter. Designed to create “a limited practice of appellate review of sentences in the Federal criminal justice system,”227 the statute does not pretend to permit appeal in every circumstance in which either the defendant or the government protests the outcome. Rather, it seeks to conserve judicial resources so that courts can move faster without becoming less fair. It appears to go about implementing those goals in a sensible way. It permits appeals for cases in which the sentencing court appears to have departed from acceptable procedure: appeals of procedural missteps could fall under § 3742(a)(1) or § 3742(a)(2). It also permits appellate review when factfinding has allegedly resulted in a misapplication of the Guidelines or a sentence outside the (here mandatory) Guideline range. In fact, it permits appeal of all those cases in which a sentence outside the Guideline range is imposed, including the reimposition of the original sentence under the solution advocated in this Comment. In each of these cases, there is a real chance the court of appeals can correct the wrong by taking a second look. The appeals that the statute bars are those in which the court of appeals is unlikely to be able to intervene—those based solely on the deferentially reviewed discretion of the sentencing judge.

In addition to being the best reading of a statute that itself is at least a sensible policy judgment, this solution is advisable to prevent jurisdictional windfalls between the plenary and § 3582(c)(2) contexts. Under this Comment’s solution, sentences imposed via § 3582(c)(2) motions are appealable in the same circumstances as sentences imposed in plenary sentencing proceedings. The alternative most circuits have adopted, permitting appeals under the general appeals statute, means that defendants are able to appeal their new sentences on more grounds than they were able to appeal their original sentences under § 3742—a jurisdictional accident.228

Conclusion

Defendants may move for modification of a term of imprisonment via § 3582(c)(2) when the Sentencing Guidelines have been retroactively adjusted downward and the reduction results in a lowered Guideline range for the defendant. Both before and after the Supreme Court rendered the Sentencing Guidelines advisory, the circuits have diverged on the appealability of such motions. Some circuits hold that they are appealable, if at all, under § 3742. Section 3742 is a grant of jurisdiction over appeals of “otherwise final sentences” if they fit into one of four specified categories, the relevant one being a sentence “imposed in violation of law.”229 Other circuits hold that they may hear appeals under § 1291, either exclusively or concurrently with § 3742. Section 1291 is a general grant of appellate jurisdiction over “all final decisions of the district courts.” The final disagreement is over the effect of the Supreme Court’s institution of reasonableness review for sentences, with some circuits holding that it expands jurisdiction to review sentences and others that it determines only the manner of reviewing otherwise appealable sentences.