The Comparative Constitutional Law of Presidential Impeachment

With the charging and acquittal of President Donald Trump, impeachment once again assumed a central role in U.S. constitutional law and politics. Yet because so few impeachments, presidential or otherwise, have occurred in U.S history, we have little understanding of how removing presidents in the middle of a term alters the direction or quality of a constitutional democracy. This Article illuminates the appropriate scope and channels of impeachment by providing a comprehensive description of the law and practice of presidential removal in the global frame. We first catalog possible modalities of impeachment through case studies from South Korea, Paraguay, Brazil, and South Africa. We then deploy large-N empirical analysis of constitutional texts, linked to data about democratic quality in the wake of successful and unsuccessful removal efforts, in order to understand the impact of impeachment on democracy. Contrary to claims tendered in the U.S. context, we show that impeachment is not well conceived as solely and exclusively a tool for removing criminals or similar “bad actors” from the presidency. Instead, it is commonly and effectively used as a tool to resolve a particular kind of political crisis in which the incumbent has lost most popular support. Moreover, despite much recent concern about the traumatic and destabilizing effects of an impeachment, we do not find that either successful or unsuccessful removals have a negative impact on the quality of democracy as such. Our comparative analysis has normative implications for the design and practice of impeachment, especially in the United States—although those implications must be carefully drawn given the limits of feasible causal inference. The analysis provides consequentialist grounds for embracing a broader, more political gloss on the famously cryptic phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” in contrast to the narrow, criminal standard that President Trump, in line with other presidents, promoted. A criminal offense standard, however, might be appropriate for judges and other officers subject to impeachment. We suggest a multitiered impeachment standard is sensible. Also against settled U.S. understandings, the analysis shows how other institutions, such as courts, can and do play a valuable role in increasing the credibility of factual and legal determinations made during impeachment. Finally, it suggests that impeachment works best where, in contrast to U.S. design, a successful removal triggers rapid new elections that can serve as a “hard reboot” for a crisis-ridden political system.

“Impeach Eisenhower. Impeach Nixon. Impeach Lyndon Johnson. Impeach Ronald Reagan.”

–Annie Hall (Charles H. Joffe, 1977)

Introduction

The president must go! Thus rings the call across many democracies, including our own. Political opposition and civil society movements have targeted elected leaders who have become politically unpopular, ineffective, or allegedly (and perhaps actually) corrupt. Impeachment discussions surged in the United States in 2016 even before President Donald Trump had taken his oath of office.1 They burst dramatically into the realm of political plausibility in September 2019 with the announcement of an inquiry in the House of Representatives, which precipitated the third presidential impeachment and Senate trial in U.S. history. Yet this specter of removal has not been distinctive to Trump. Impeachment talk also dogged his predecessors.2 Nor should Americans think their discontents unique. In France, the gilets jaunes protest movement has been candid in its “hatred” for President Emmanuel Macron and its desire to see him ousted from office.3 And in Venezuela, an opposition leader went so far as to declare himself “interim president” in a (so far, vain) attempt to accelerate the departure of a well-entrenched presidential incumbent.4 Regime change has yet to arrive in Caracas, Paris, or Washington, D.C. But presidents have no cause to rest easy. In democracies as diverse as Brazil, South Korea, and South Africa, presidents have been removed in the middle of their term in the past decade.5 Impeachment talk is not necessarily idle chatter. At least in some instances, it is a credible position that can attract sufficient political and popular support to be realized.

The removal of a president from office by a mechanism other than through the regular operation of elections, term limits, and the normal apparatus of political selection goes to the core of democratic governance. This is a moment of increasing popular discontent with established regimes, coupled with a growing polarization within the voting publics of many democracies.6 Under those conditions, it is perhaps unsurprising that elected tenures would prove to be fragile, and talk of preemptive removal and impeachment endemic.

Nevertheless, legal scholars and social scientists have until now lagged behind the roiling wave of popular sentiment. To be sure, there is a wealth of scholarship on the role of impeachment in the U.S. Constitution.7 That work—much of it excellent—starts from the Framers’ design, and then reasons from that design to present applications.8 As a result, it explores a relatively narrow compass within the space of possible constitutional design. It does not help that the “Constitution is surprisingly opaque as to how apex criminality should be addressed.”9 The U.S. Constitution’s text, for example, uses the ambiguous term “high Crimes and Misdemeanors”10 to define a threshold for presidential removal. It is no surprise that Trump, like his predecessors, insisted that this included only statutorily defined crimes.11 The Constitution also fails to specify a standard of proof for either impeachment or conviction. Again, it is no surprise that both the President’s defenders and his prosecutors each have asserted their own favored substantive standards of impeachability.12 Finally, the text conspicuously fails to specify clearly whether a sitting president can be indicted prior to the completion of impeachment proceedings.13 The result is a process of deeply uncertain scope and consequences.14 Arguments about many of these uncertainties—not just in the context of the Trump impeachment, but beyond—necessarily hinge on predictions about the consequences of presidential ouster.

With many other constitutional questions, our post-ratification history can provide clarity about consequences. Not so here. To date, there have been only three successful presidential impeachments; no sitting president has ever been removed.15 We thus simply have no basis for knowing whether impeachments tend to shore up democracy, or whether they undermine it.16 The impeachment language in Articles I and II is largely (if not wholly) general, extending beyond presidents to encompass judges and certain officials.17 But the history of nonpresidential removals is also of limited use. Presidential impeachments plainly raise empirical questions, legal problems, and normative concerns beyond those implicated by the removal of federal judges and other officials. Most obviously, the electoral mandate that presidents, unlike unelected actors, possess raises a distinctive question about the democratic legitimacy of impeachment-like removal mechanisms, such as criminal prosecution or declarations of incapacity, that bypass the people.18 There is a distinct and pressing question whether impeachment is consistent with the principle of popular sovereignty that underwrites democracy—or whether it is at odds with democracy as a going concern.

One analytic pathway, however, remains relatively uncharted. At the same time as the focus of U.S. scholars narrows, there remains a dearth of legal scholarship leveraging other countries’ experience with presidential removal.19 While some political scientists have documented the relatively low success rate of calls for removal globally,20 no one has systematically examined the design of presidential impeachment from a comparative perspective. This is not for want of relevant evidence. As we shall show, the design of removal procedures for chief executives is almost uniformly a matter of constitutional text, not exclusively statutory policy. This reflects a (perhaps undertheorized) assumption that the question is an important one to be insulated, to some extent, from transient politics. The sheer proliferation of presidential removal provisions also suggests that there is a common problem to which constitutional designers around the world are responding. It could well be that designers are responding to slightly different understandings of a general problem, and are doing so under very different conditions of democracy (or lack thereof). Wide variance in context and conceptualization of governance problems might exist. Yet the observation of a common design choice suggests that there is something to be learned through comparison. Certainly, there is no reason to assume that the United States is “exceptional” among presidential regimes in the functions played by impeachment. That is a kind of intellectual parochialism that we think wise to avoid from the get-go.21

Examination of impeachment provisions and practices globally is relevant to a number of questions fundamental to a democracy.22 At a minimum, it seems important to know whether the substantive and procedural elements of the U.S. system are distinctive, or outliers as a matter of constitutional design. Relatedly, a global view of impeachment can illuminate its potential function in a constitutional democracy, and hence suggest how its scope and mechanisms might be reconciled with electoral democracy. When should a democratic mandate be superseded because of the perceived costs of allowing the people’s choice to remain in power after some form of wrongdoing? If supersession is to be allowed, should it be through a political process (defined and judged according to partisan standards), or a more formalized, law-governed process (say, defined by the criminal law)? And what mechanisms, institutions, and procedures should be involved in the removal process? Should they be other elected actors, or nonelected, professional institutions? What should be the result of a presidential removal: a new election, or either an ally of the president or someone else taking control of the government?

This Article analyzes the problem of presidential impeachment or removal through a comparative lens. We present here the first comprehensive analysis of how constitutions globally have addressed this question, and what the consequences of different design choices are likely to be. Because actual removals of chief executives turn out to be rare (although calls to remove are much more frequent), we employ a twofold empirical strategy. We begin by developing five case studies, including the United States, of removals that occur through a range of procedures and under quite different political conditions. This granular approach helps pick out some of the variation in constitutional technologies of presidential removal. It also offers clues as to what legal and political factors matter in practice. Causal inference, to be sure, is perilous given the small number of observed outcomes and the endogeneity of observed outcomes to institutional choices. That is, because presidential behavior will be influenced by the choice of substantive and procedural impeachment rules, it is not feasible to isolate the effect of those rules on decisions to impeach. Because the law influences both the independent variable of impeachable acts and the outcome of observed impeachments, no crisp causal inference is possible. Rather, we tentatively view different structural arrangements as inducing different patterns of both underlying behavior and removal-related responses. Next, we zoom out to offer a comprehensive, large-N description and evaluation of the relevant constitutional design choices. Finally, we draw carefully nuanced conclusions about the normative stakes of varying design decisions in this domain.

Before summarizing our key descriptive findings and normative suggestions, we should clarify the universe of cases that we are considering. Removal of a chief executive is a necessary power in any political system, whether presidential, parliamentary, or otherwise. Even traditional monarchies had procedures for removing kings who were incapacitated or incompetent.23 Our focus, however, is primarily on fixed-term executives, who tend to be called presidents.24 Such officials are found in an array of political systems, including presidential systems, semi-presidential systems,25 and even some parliamentary systems.26 We include heads of state in parliamentary systems, who tend to have a more ceremonial role, but exclude prime ministers (who are typically disciplined instead through a parliamentary “vote of confidence” mechanism).27

We show first that impeachment does not always focus on the criminal behavior or bad acts of an individual president. Rather, it also serves as a response to a particular kind of political crisis in a presidential system, commonly in which public support for the leader has collapsed. In some recent impeachments, such as in South Korea, crisis combined with evidence of criminality to oust a president from office.28 But in other cases, such as in Brazil and Paraguay, there was scant evidence of apex criminality.29 Removal was rather used to push out weak presidents who had lost the ability to govern. Consistent with this practice, many constitutions around the world include a textual standard for removal that explicitly goes beyond criminality to include governance failures or poor performance in office, while others enable such an approach through ambiguity. Generalizing from textual evidence and case studies, we suggest that impeachment globally is, in practice, a device to mitigate the risk of paralyzing political gridlock, rather than simply a way to deal with individual malfeasance. A second important empirical conclusion follows. Examining measures of democratic quality in impeachment’s wake, we find no evidence (at least in the small sample of extant cases) that impeachment of a president reduces the quality of democracy in countries where it is carried out.30 The same holds true when removal through impeachment is attempted, but not completed. The fear that a more political impeachment process would necessarily be destabilizing has no empirical support in the recent comparative experience. Rather than being a way of undermining or circumventing democracy, we suggest that in fact impeachment may play an important role in its stabilization.

Although we tread carefully in drawing normative conclusions given the limited pool of available data and endogeneity concerns, our analysis nevertheless has implications for the design and practice of impeachment, particularly in the United States. We argue that a model of impeachment focused only on the individual culpability of chief executives—what we call a “bad actor” model—is likely incomplete and undesirable as a functional matter. Instead, impeachment processes should be attentive to the broader political context, which we call a “political reset” model. Impeachment can be useful to ameliorate one of the major weaknesses of presidentialism—rigidity31 —by removing poorly performing presidents when their support has collapsed.

Professor Stephen Griffin has recently tracked the history of impeachment discourse in the United States to show that partisan dynamics forced it into a Procrustean bed of “indictable crimes” and nothing more.32 Consistent with Griffin’s careful analysis, Trump’s legal team argued in the Senate that the House’s articles were deficient in part because impeachment was only appropriate in the event of a violation of “established law” and, likely, “criminal law.”33 We think, to the contrary, that the comparative evidence suggests that such a narrow interpretation of the term “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” may well be problematic. A broader, more political meaning of this notoriously cryptic standard may make more functional sense as an element of a well-functioning democracy.

Aside from shedding new light on the well-studied issue of “high Crimes and Misdemeanors,” our analysis also critiques a range of crucial but less studied features of impeachment in the United States. Some are a product of judicial or political practice; others would require a constitutional amendment to fix. All are taken as givens—in quite problematic ways. For example, we highlight the striking fact that the impeachment standard in the United States is uniform across different types of actors, such as presidents, judges, and cabinet members, rather than varying as in many other countries. We think a more differentiated approach makes more sense. Impeachment of different kinds of actors serves different purposes, and it makes little sense to use a one-size-fits-all approach. We also highlight the ways in which actors other than legislatures contribute fact-finding, legitimacy, and other benefits to impeachment processes in some contexts. In particular, and contrary to the settled understanding in the United States and the leading precedent,34 we suggest that a more robust role for courts in impeachment processes may be consistent with a political, regime-centered model of impeachment. In some contexts, courts can lend credibility to factual and legal determinations made during impeachment—a credibility that has been in short supply during recent processes in the United States. Finally, our analysis suggests that impeachment design in the United States fails to maximize its value by having the vice president (or a similar actor) automatically succeed to office, rather than calling new elections. We think that calling new elections after a successful impeachment is a superior option because it increases impeachment’s ability to serve as a reset for a crisis-laden system.

We recognize that this topic is of great current interest in the United States, largely because of the recent impeachment trial and acquittal of Trump. Indeed, there is a growing academic and nonacademic literature on the topic of his impeachment.35 Some of these contributions confront Trump’s actions in light of the relevant standard; others are more abstract treatments not limited to the particulars of his case. We place ourselves in the latter camp, abstracting away from the current presidency, and avoiding inevitably partisan implications in the hope of generating more durable insights. At the same time, we also recognize that the occasion of the Trump impeachment and acquittal seems to be a particularly good moment to stimulate careful reflection on an important constitutional issue.

Our analysis is organized as follows. Part I motivates our analysis by presenting case studies of recent instances of presidential removals from around the world: South Korea, Brazil, Paraguay, and South Africa. We also briefly survey U.S. law and experience to benchmark domestic experience. Part II draws on large-N empirical evidence to describe and analyze the history, rules, and practice of presidential removal globally. We find that impeachment is often a response to governance problems related to waning public support for a fixed-term leader. It thus extends beyond the standard bad actor model that dominates much of the American legal discourse. Systems vary in terms of both the predicate acts that can trigger impeachment along with the process, including both the actors involved and the various rules governing time and consequence. Finally, Part III draws on this evidence to theorize better impeachment institutions, focusing on implications for the United States. We conclude by suggesting that at least as a prima facie matter a more frequent, systemic use of impeachment in presidential democracies, including our own, should not be feared. It is likely to do more good than harm.

I. The Irresistible Rise of Impeachment: Snapshots from the World of Presidential Removal

We begin by considering the three most recent cases of successful removal by impeachment—in South Korea, Brazil, and Paraguay—along with the removal of President Jacob Zuma midway through his second term in South Africa as a consequence of a protracted corruption-related investigation. These case studies are useful for “clarifying previously obscure theoretical relationships” and as a step toward “richer models” than would be enabled by purely large-N analysis.36 The case study approach is especially appropriate here because, as we demonstrate in Part II, the rate of successful impeachments in the past half century or so turns out to be small in comparison to the denominator of elected chief executives holding office, or even the number of proposals for impeachment.37 Impeachment is often proposed and rarely realized. A case study approach allows a thick account of most of the relevant positive instances of impeachment or removal that would be missed by a large-N analysis alone. Finally, by way of counterpoint (and to tee up our normative analysis in Part III), we recapitulate briefly the historical framing and practice of impeachment in the United States as a point of reference and contrast.

In each of our first three case studies, directly elected presidents did not finish their terms, albeit for different reasons. South Korea’s President Park Geun-hye was removed from office in 2017 after an impeachment confirmed by the Constitutional Court. Brazil’s President Dilma Rousseff was removed in 2016 shortly after her reelection to a second term in relation to an alleged fraud scheme. And Paraguay’s President Fernando Lugo was removed from office in 2012, primarily on the grounds that he had botched policy decisions prior to and after a massacre involving a land invasion. In each of these cases, the ousted presidents were extremely unpopular. Their ousters constituted a political opening, consequently, for political opponents, who gained new access to the levers of power. In South Africa, in contrast, where presidents are selected by the Parliament rather than directly elected, Zuma was replaced by a leader of his own party, after losing support from within the party.

In our view, all of these removals had normative justifications, albeit ones not necessarily anchored in the specific criminal acts of a given leader. But the political outcomes they produced were radically different. For example, after removing the incumbent, South Koreans elected a left-wing candidate, President Moon Jae-in, while Brazilians chose a fiery right-wing populist, President Jair Bolsonaro. His tenure is still too new to evaluate, but concerns about democratic backsliding and state violence have deepened. In contrast, Zuma was replaced by his copartisan President Cyril Ramaphosa, who went on to lead the African National Congress (ANC) party to a close election win. In most of these cases, the system has found a new equilibrium, and democracy has not fallen.

A. South Korea: The Park Impeachment

The South Korean Constitution allows impeachment for a “violat[ion of] the Constitution or other laws in the performance of official duties.”38 A majority of members of the National Assembly can propose an impeachment bill for the president, which must then be approved by a two-thirds vote.39 The president is immediately suspended from serving; his or her duties pass on to the Prime Minister.40 In a second stage, the impeachment motion then goes to the Constitutional Court for final approval.41

In the first Korean impeachment of the twenty-first century, this last step proved dispositive. In 2004, President Roh Moo-hyun was impeached.42 Before the Constitutional Court could decide on the question of removal, an intervening parliamentary election gave Roh’s party a slim parliamentary majority.43 The court, perhaps in a move of political pragmatism, decided that the charges against Roh were not sufficient to warrant removal.44 Roh went on to serve to the end of his term, though he eventually committed suicide during a corruption probe.45 The Constitutional Court’s decision was systemically important for clarifying many of the relevant rules.46 Most importantly, it held that even if charges against a president were well-founded, removal should only occur if there was a grave violation of law and if removal was “necessary to rehabilitate the damaged constitutional order.”47 The court also explained the division of labor in impeachment cases, holding that the Assembly had a political and fact-finding role, while the bench itself was the ultimate judge of whether the facts presented met the legal threshold for removal.48

A decade later, a second South Korean president faced defenestration. This time the court ratified some of the grounds for impeachment. President Park Geun-hye, like most Korean presidents, found her popularity dropping precipitously after her 2012 election.49 In 2016, it was revealed that she had been taking instruction from, and acting on behalf of, a close confidant, Choi Soon-sil.50 Choi’s father had been the head of a secretive cult and an associate of Park’s father, President Park Chung-hee. Choi had been extorting money from Korea’s large business corporations. When these facts were revealed, massive public demonstrations ensued and the opposition party filed impeachment motions against Park.51 The charges included seven counts, including, inter alia, abuse of power, violating the duty of confidentiality by sharing government documents with Choi, and violation of the right to life in the Sewol ferry disaster, which had taken the lives of hundreds of high school students in 2014. Several members of Park’s own Saenuri Party joined in passing the motion by the required two-thirds vote, and Park was suspended as president.52 As in Roh’s case, the Constitutional Court then initiated its proceedings.

On March 10, 2017, the court delivered a verdict upholding Park’s impeachment on three of the seven counts: violation of the obligation to serve the public interest, infringement upon private property rights, and violation of confidentiality.53 Her interactions with the “shaman or medium” Choi were central to this finding, as they were to the growing tide of public anger at her administration’s corruption.54 The court did not accept three other grounds for impeachment, including one based on allegations related to the Sewol ferry disaster, and it found a final charge—the “obligation to faithfully execute the duties of the President”—to be nonjusticiable.55 The court then held that these charges met the test for seriousness laid out during the Roh impeachment case because they gave a private citizen influence over the office of the presidency.56 Park was subsequently convicted in criminal court. She is currently serving a twenty-five-year prison term.57

Under the South Korean Constitution, an impeached president is replaced by the prime minister, a weak vice presidential figure without independent executive authority. Moreover, the prime minister assumes presidential duties as soon as the impeachment charge is approved by the National Assembly, while the Constitutional Court conducts its trial. Importantly, though, the Acting Presidency lasts only until a new presidential election can be held, a period of no more than sixty days.58 After Park’s removal, Prime Minister Hwang Kyo-ahn remained in office until new elections in May 2017 brought in Moon Jae-in.59

In our view, the removal of Park before her five-year term ended was a model of procedural integrity. The impeachment decision by the Constitutional Court laid out in depth the extent to which Park had given over the public trust to a private individual, with no official position or relevant experience. It resolved a major political crisis in which hundreds of thousands of people were demonstrating in Seoul. The court’s judgment, moreover, provides a model of sober evaluation of the evidence, rejecting superfluous charges while upholding those for which the evidence was clear. At the same time, the court’s careful election of some impeachment grounds over others seems to have tracked the nature of public discontent at the perceived dysfunctionality of the Park government.

B. Brazil: The Rousseff Ouster

Shortly after President Dilma Rousseff had been elected to her second term in office as Brazil’s president, a scandal known as “Operation Car Wash” revealed massive corruption tied to Brazil’s state-owned oil company during the period she had been in charge of it before becoming president.60 Though no evidence emerged that she was personally involved, Rousseff was held politically responsible for the failings of her party’s (the Worker’s Party, or “PT”) long period in governance. With public discontent at PT’s perceived corruption rising, opponents began to look for a hook to remove her. In late 2015, Rousseff was charged with a violation of article 85 of the constitution, which details the grounds for impeachment.61 Just like previous presidencies, Rousseff’s administration had engaged in an accounting maneuver to try to make it look as if the government had more assets than it did. The maneuver allowed it to allocate funds to social programs without direct allocation from the Congress. A tax court held the maneuver to be illegal, opening the door to an impeachment that many analysts believed to be primarily partisan.62

The substantive grounds for impeachment in the Brazilian Constitution are ambiguous. Article 85 states:

Acts of the President of the Republic that are attempts against the Federal Constitution are impeachable offenses, especially those against the: I. existence of the Union; II. free exercise of the powers of the Legislature, Judiciary, Public Ministry and constitutional powers of the units of the Federation; III. exercise of political, individual and social rights; IV. internal security of the Country; V. probity in administration; VI. the budget law; [and] VII. compliance with the laws and court decisions.63

Article 85 of the Brazilian Constitution thus lays out a fairly broad and reasonably political—as opposed to strictly legal—standard for impeachment, which seems to reach well beyond criminality. It also includes a “by law” clause giving legislation the power to further define both the standards and process for impeachment. The relevant law, Law 1079, was passed in 1950, and so predates the current constitution of 1988, although the law was amended more recently.64 The law, oddly, conflicts with the constitutional text in certain key respects. Some commentators have suggested the law may play a bigger influence on impeachment in practice than the constitution itself.65 The law fleshes out the broader categories found in article 85, but still maintains a definition of those terms that is highly political in nature.

The allegations against Rousseff focused on crimes against the administration and the budget, chiefly (as noted above) that she disbursed public money without congressional authorization.66 The allegations also linked Rousseff to the Operation Car Wash scandal, albeit indirectly. More specifically, it was argued that she had failed to act with sufficient vigor against participants in the scandal.67 This latter allegation, however, did not become the basis for impeachment, which instead focused (at least formally) solely on the alleged illegal appropriations.68

Article 86 of the constitution fleshes out the bare bones of the process of impeachment of the president, which again is regulated more closely in Law 1079 and in internal congressional bylaws.69 Under that process, the lower House investigates accusations and decides whether to impeach the president, by a two-thirds vote. Cases then proceed either to the Senate (in cases of “impeachable offenses” defined in article 85) or to the Supreme Court (in cases of “common criminal offenses”), for the final trial.70 Once the Senate begins removal proceedings, the president is suspended for up to 180 days during the trial. A two-thirds vote of the Senate is required to remove officials from office for commission of an “impeachable offense.” As in the United States, the president of the Supreme Court must be present and must preside over the trial that occurs in the Senate.71

In 2016, Rousseff was formally impeached by the required two-thirds vote in the lower house on a vote of 367–13, and trial commenced in the Senate.72 When the Senate voted to initiate removal proceedings, Rousseff was suspended and Vice President Michel Temer took over as acting president. Temer retained this position after the Senate voted on August 31 to remove Rousseff from office, again by a two-thirds vote of 61–20, from August 2016 until the end of 2018.73 But at the same time, the Senate failed to reach a two-thirds supermajority to deprive Rousseff of her political rights for eight years. As a result, she retained the ability to run for future office (and indeed ran unsuccessfully for a Senate seat in 2018).74

The Supreme Court played a complex, multilayered role throughout the episode as an agenda setter and adjudicator of key procedural choices. Unlike its South Korean analogue, however, it exercised no ex post review once the legislative part of the impeachment process had come to its conclusion. Actors on all sides of the political spectrum bombarded the bench with a series of challenges and requests throughout the impeachment process. The court’s response was mixed. On the one hand, the court generally avoided judging the substantive question whether the allegations against Rousseff were sufficient for impeachment, demurring to the legislature.75 On the other hand, it issued some judgments that impacted the process in meaningful ways. For example, the court issued a ruling in December 2015, when the impeachment process was just beginning, that allowed the process to go forward but held that the committee investigating Rousseff needed to be reconstituted because it had previously been stacked with proponents of impeachment, in violation of the relevant laws and regulations.76 Membership in the committee, directed the court, needed to be proportional to the composition of the House.77 The court also held that the Senate, as well as the House, should issue a preliminary vote on whether to accept the impeachment allegation against Rousseff.78

It is worth noting that, as in South Korea, the recent Brazilian impeachment had a historical precursor: President Fernando Collor de Mello’s ouster in 1992, shortly after Brazil’s transition to democracy.79 The latter shared key features with Rousseff’s removal. As with Rousseff, political context rendered Collor vulnerable to impeachment. He was an outsider president without strong ties to existing parties; he hence had great difficulty building a governing legislative coalition. Collor was forced to resort aggressively to unilateral decree powers because of his lack of partisan support, often reissuing provisional decrees before they could expire.80 Opponents alleged that this practice was abusive. It was eventually restricted by the Supreme Court and then by a constitutional amendment.81

The immediate triggers for Collor’s impeachment were corruption allegations. The House’s charges did not allege any specific crimes, but rather facilitating “the breach of law and order” and behaving in a way that was inconsistent with the “dignity” of the presidential office.82 Collor argued that noncriminal acts could not be the basis for impeachment. But the House and Senate proceeded to impeach him regardless. Collor technically resigned before the impeachment was completed, but the Congress nonetheless finished the process, with the Senate voting in favor by an overwhelming 76–3 vote. As in the Rousseff impeachment, judges played a major role in Collor’s: the president of the Supreme Court, in his role presiding over the Senate trial, crafted special rules that simplified and streamlined some of the procedures found in Law 1079.83

What lessons does the Rousseff impeachment (and its echoes in the Collor impeachment) hold for the comparative study of presidential removal? To begin with, unlike the Park ouster in South Korea, it is hard to conceptualize Rousseff’s impeachment as being about criminal behavior, or even serious moral wrongs, of the President herself. The acts that formed the basis of her impeachment—basically, accounting tricks and related devices to authorize additional social spending, allegedly with the intent of helping the PT retain power—had been engaged in by presidents prior to Rousseff. Even the broader context for the allegations and impeachment, which revolved around alleged involvement with the Operation Car Wash investigation, did not yield much evidence inculpating Rousseff herself. Rather, she was accused of negligence in handling accusations and being connected to involved actors. But these accusations did not meaningfully distinguish her from the larger political class. So it is perhaps unsurprising that Rousseff’s impeachment prompted outcry in some quarters and was described by her and her allies as a coup.84

The political framing of the impeachment resonates even more when Brazil’s recent political history is brought into the analysis. Rousseff’s 2014 reelection campaign had been fought in a context where the revelations of the Operation Car Wash investigation started to discredit the country’s political class as a whole. When she won reelection in 2014, it was by a much smaller margin than in 2010.85 Indeed, her PT party lost support in Congress. In consequence, she was forced to rely on a more fluid pattern of support without a clear majority coalition to legislate. The president of the House, Congressman Eduardo Cunha, was never an ally of the PT and became strongly opposed to it in mid-July 2015; his party (the second largest in the House) turned against Rousseff during the impeachment process, depriving her of needed support. The theory of the case against Rousseff also “echoed the street protests” against the PT more generally.86 At the time, the economy in Brazil was experiencing an extended period of stagnation.87

But, crucially, the impeachment did not reset the political system. New presidential elections did not occur until 2018. Instead, Temer took over the chief executive’s role. As a result, PT allies saw the impeachment, as well as related actions like the jailing of former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, as an attempt by more traditional and conservative actors to take down the country’s most organized progressive force.88 Temer served for about two and a half years after Rousseff’s suspension, but was a weak and unpopular president. He had already been implicated in corruption more directly than Rousseff, as were many of those who remained in Congress.89 The discrediting of Brazil’s political class en masse continued; space thus opened for self-styled outsider and right-wing populist Jair Bolsonaro to win election in 2018.

Bolsonaro has not been immune from impeachment talk, either. Notorious for consistently dismissing the COVID-19 virus as the “little flu,”90 Bolsonaro’s erratic performance and authoritarian rhetoric have led to calls for his impeachment from Lula, among others.91 At the time of writing, some forty-eight petitions for impeachment are before the Speaker of the House, though it is not clear whether he will let them advance.92 This is in part because Vice President Hamilton Mourão, whose popularity exceeds that of Bolsonaro, is considered a wild card himself with possible authoritarian leanings. The lack of a reset option has worked to Bolsonaro’s advantage.

C. Paraguay: The Removal of Lugo

The removal of Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo by Congress in 2012 is another case which is difficult to interpret as the removal of a criminal or morally depraved leader. A former Catholic bishop and political outsider, Lugo won the presidency in 2008 on the ticket of a small party and in alliance with seven other political parties, ending over sixty years of rule by the Colorado Party.93 In return for the support of the largest opposition party, the Liberal Party, he picked an insider vice president, Federico Franco, with Liberal bona fides.94 Lugo and his vice president were not close. There were rumors from early in Lugo’s term that the Liberals were seeking to supplant him with Franco.95 Further, Lugo was unsuccessful at carrying out most of his initially ambitious political and economic programs, especially on his signature issue of land reform, and over time his popularity fell sharply.96 He was unable to pass any significant legislation in a deeply divided Congress. His own coalition remained highly factionalized.97 There was considerable instability during Lugo’s term, with other impeachment attempts prior to the successful one. A failed military coup led to Lugo’s replacement of the entire military leadership in 2009.98

The proximate cause for the Lugo impeachment was an incident on June 15, 2012, where seventeen people (six police officers and eleven farmers) were killed.99 Landless farmers occupied land estates that they alleged had been unlawfully acquired, leading to the clashes. The impeachment charges laid against Lugo focused on this incident, as well as four others,100 and complained in general terms of “bad performance in office.”101 Referring to the ki-llings, the charging document also stated sweepingly that Lugo had exercised power in an “inappropriate, negligent and irresponsible way . . . generating constant confrontation and war between social classes.”102 It did not accuse Lugo, though, of committing a crime. Like the Brazilian organic law, the Paraguayan Constitution explicitly allowed impeachment for poor political performance.103

A lightning-fast process of impeachment began and ended within the space of mere days. On June 21, 2012, the Chamber of Deputies voted to impeach Lugo by a 76–1 vote; the next day, the Senate voted to remove him from office by a 39–4 vote.104 The rules required a two-thirds vote of those present in the Chamber of Deputies for impeachment and a two-thirds absolute majority of members of the Senate for removal. Both thresholds were easily met.105 Under the constitutional framework in force, the vice president and Liberal Party member Franco, who had become a manifest opponent of Lugo, then became president.106

Lugo and his allies complained of a lack of due process in his impeachment. They pointed to the breathtaking speed of the impeachment and the fact that he was offered only two hours to appear before the Senate to present his defense. Like Rousseff and her allies, regional leaders condemned the removal as an “institutional coup.”107 The leaders of many other countries in the region agreed.108 Paraguay was in fact suspended from regional organizations Mercosur and Unasur until the next set of elections were held in the country in 2013.109 The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights issued a statement calling the speed with which the removal was carried out “unacceptable” and stating that it was “highly questionable” that the removal of a Head of State could be “done within 24 hours while still respecting the due process guarantees necessary for an impartial trial.”110 It concluded that the speed of the procedure raised “profound questions as to its integrity.”111

It is hard to see the Paraguayan example, with its extraordinary speed and resulting lack of deliberation, as a model of how impeachment should be done. At the same time, the case shows how impeachment can work more as an attempted exit from a political crisis rather than a judgment of criminal behavior (or serious wrongdoing) by the incumbent. Like the Rousseff removal, but even more clearly, the impeachment of Lugo did not focus on his culpable status as a “bad actor.” The opponents of Lugo did not argue that he had committed a statutory crime. Instead, they relied on his “poor performance of duties” (mal desempeño de sus funciones) in office, a noncriminal ground of impeachment expressly contemplated in the Paraguayan Constitution.112

As in the Park and the Rousseff cases, it appears that a decisive factor in Lugo’s impeachment was the fragility of his political support. Lugo was removed because he had lost the support of nearly the entire political class, including most of his own coalition, and was deeply unpopular. The Liberal Party, for example, resigned en masse from Lugo’s cabinet just before the impeachment began.113 Lugo appealed his removal to the Supreme Court, but the court summarily dismissed the petition in a brief order, using reasoning similar to that of the U.S. Supreme Court when confronted with challenges to impeachment procedures. It held that the process of impeachment was delegated to the legislature and that the court had no basis to intervene.114

In effect, then, the Paraguayan impeachment process operated as a (supermajoritarian) vote of no confidence in the president. There are similar regime dynamics in the South Korean and (especially) Brazilian contexts as well, where the criminal allegations sometimes seem to be used as cover to remove unpopular presidents who had lost an enormous amount of congressional support. The Paraguayan impeachment is the clearest case of removal operating to address political deadlock rather than particular individualistic flaws.

D. South Africa: The Ouster of Zuma

We now turn to a case in which a president was in effect removed, albeit in the end through a resignation rather than the culmination of a formal process of removal: the ejection of Jacob Zuma from office in the middle of his term as South Africa’s president in early 2018. Although South Africa has a president with a substantive rather than a ceremonial role, the 1996 South Africa Constitution is more akin to a parliamentary rather than presidential system. The president is not directly elected by the public, but chosen by the Parliament. Moreover, as with prime ministers in parliamentary systems, the Parliament has the ability to force the resignation of the president by voting no confidence in him or her at any time.115 Since 1996, the position has always gone to the head of the dominant African National Congress. Under conditions of ANC hegemony, the president will continue in office so long as he or she can maintain the support of members of the party.

But, under section 89 of the constitution, the president can also be removed by a two-thirds parliamentary supermajority via an impeachment-like procedure, in the event of a serious violation of the constitution or law, serious misconduct, or an inability to perform the functions of the office, and a figure removed in this way may not receive any benefits of the office or serve in any public office in the future.116 Even though the position of president in South Africa is more like that of a prime minister in other systems, we discuss the case briefly here because it highlights some mechanisms that may facilitate a successful removal process, especially the involvement of other, nonparliamentary institutions.

The Zuma presidency was characterized by an acute crisis of corruption. During the tenure of his predecessor President Thabo Mbeki, an “ANC party-state” developed in which party loyalists were assigned to high posts in public office, parastatals came under party control rather than state control, and ANC elites increasingly dominated the “commanding heights” of the private economy.117 During the Zuma presidency, the state was captured by a small group of private actors, who steered public contracts to preferred businesses in exchange for kickbacks.118 Ministers who declined to cooperate were quickly relieved of their duties and office.119 As a result of ineffectual or corrupt presidential leadership, a raft of structural, macroeconomic problems accumulated.120

Zuma did not keep his hands clean. His country residence “Nkandla homestead” in KwaZulu-Natal became an epicenter of public controversy as a result of a publicly funded security upgrade ultimately costing some R246 million.121 At least initially, the ANC resisted attempts to hold him accountable. Without an internal check from his party, and with that party playing a dominant role in the country’s politics, there was a real risk of the erosion of democracy itself. But the prosecuting and investigating institutions of the state were not particularly active in seeking to hold Zuma accountable. Only the Public Protector, an ombudsman-like body with relatively weak powers, seemed to be willing to challenge Zuma’s corrupt behavior and the larger problem of state capture.

In this context, the Constitutional Court intervened several times to both protect opposition rights within the Parliament, and also to require Parliament itself to maintain and use mechanisms for presidential accountability. Hence, the court strongly suggested that votes on no confidence in the president had to be secret.122 It also insisted that minority rights in Parliament not be squelched.123 It then held that the Speaker of the House could not simply ignore a motion of no confidence challenging Zuma’s continued tenure.124 Parliament had a duty to hear such motions, the court instructed.125 In a particularly critical decision, the court empowered the Public Protector, whose findings were given legal force.126 The Public Protector had issued a report that followed an investigation into the use of public funds for the improvement of the President’s Nklanda residence. The report concluded that money misspent on portions of the upgrades should be repaid by Zuma. The President failed to comply with the findings, claiming that they constituted mere “recommendations.”127 The court, however, held that such findings were legally binding and that the President was not entitled to disregard them. It also held that Parliament had to come up with a mechanism to hold the president accountable. Importantly, the Public Protector’s report concluded that in receiving undue benefits from the state, the President had breached “his constitutional obligations.”128 Many regarded this statement, now imbued with the force of law, as fulfilling the criteria for impeachment set forth in section 89(1) of the constitution.129

Despite this, Zuma subsequently survived a secret ballot of no confidence in August 2017.130 The narrowness of the vote margin, though, demonstrated the extent to which Zuma and his allies had lost support within the parliamentary ANC party. “It thus anticipated, and rendered more likely, Zuma’s ultimate February 2018 ouster.”131 The ANC effectuating a removal of its own leader is a remarkable instance of an intraparty check on power. Such intraparty checks are quite rare in true presidential systems and are likely to reflect the strategic calculation of party insiders of how to minimize electoral losses due to an unpopular elected figurehead.

In short, the South African Constitutional Court forced the political system to act. It did not directly remove the President, but it ensured that the processes of democratic accountability could not be ignored. The Public Protector also played the vital role of documenting “state capture” in a form that Zuma could not easily ignore. At least formally, the Zuma case is a “near miss” rather than an impeachment.132 But it illustrates how institutional processes can cause a collapse in public support for a leader, which can make their continuance in office untenable. Across all these cases, the formal processes of removal operated in tandem with, and were entangled in, changing public sentiment with respect to the presence of not just personal malfeasance, but also a systemic crisis of governance. The South African case thus confirms that presidential removal operates as a way of expressing concern about systemic crisis, even if the causal relationship of legal censure mechanisms to public disapproval varies from the earlier cases.

E. Impeachment in the United States

With the recent cases of South Korea, Brazil, Paraguay, and South Africa in hand, it is useful to return to the United States.133 Removing a sitting president in the United States through impeachment has been described as “the most powerful weapon in the political armoury, short of civil war.”134 Yet this is in some tension with the thinking at the Philadelphia Convention, where there is evidence of a rather more capacious concept. The delegates to that Convention borrowed the institution of impeachment from English law, where it had been a device to discipline and remove the king’s ministers.135 Indeed, over the centuries, it provided a central power of parliamentary accountability in the United Kingdom, but was not limited to serious crimes.136 Even while the debates about the Constitution were ongoing, for example, Edmund Burke was spearheading an effort to impeach Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General of India, for “high crimes and misdemeanors” in the form of gross maladministration.137

The formation of the constitutional text on impeachment followed from one of those exchanges between two delegates that admits of speculation, inference, and endless conjecture: one of the early iterations of the impeachment mechanism considered by the 1787 Constitutional Convention limited impeachment only to cases of treason or bribery.138 But George Mason of Virginia worried that those bases would be insufficient to remove a president who committed no crime but was inclined toward tyranny.139 Mason proposed adding “maladministration” as a basis for impeachment and removal from office, which would have made our system more like a parliamentary one.140 When James Madison objected that maladministration was a vague term, Mason then proposed the usage “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”141 It was that language that was ultimately adopted in the Constitution.142 The Mason-Madison exchange suggests that a narrow “bad actor” model fails to exhaust impeachment’s purpose. Yet it also allows different inferences about how far beyond that model the text ought to extend.

As a congressional report issued during the impeachment of President Richard Nixon recounts, the phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” had been first used in 1386 during a procedure to remove Michael de la Pole, the first Earl of Suffolk.143 The Earl’s failures included negligence in office and embezzlement. He had failed to follow parliamentary instructions for improvements to the king’s estate and had failed to deliver the king’s ransom for the town of Ghent, letting it fall to the French as a result. For these failures, Suffolk became the first official in English history to lose his office through impeachment.144 Impeachment was subsequently used episodically throughout English history,145 before falling into desuetude with the creation of modern parties and the emergence of the “ministerial responsibility” principle.146 Under ministerial responsibility, a minister can be removed simply on a lack of confidence, which makes removal a purely political matter without need for a legal proceeding. Impeachment was last used in the United Kingdom in 1806.147 Drawing on this history, the Nixon-era congressional report concludes that “the scope of impeachment was not viewed narrowly.”148

The ratification debates contain further evidence of this “political” understanding. Hence, Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 65 that impeachment would be addressed at “those offences which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated political, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”149 Subsequently, Madison, speaking at the Virginia ratification convention for the Constitution, intimated a fundamentally political purpose to impeachment. When Mason raised concerns about the breadth of the pardon power and the possibility that a president would use it to establish tyranny, noting that a president could use it to pardon crimes that “were advised by himself,” Madison responded that impeachment would be the appropriate remedy in such a case:

There is one security in this case to which gentlemen may not have adverted: If the President be connected in any suspicious manner with any persons, and there be grounds to believe he will shelter himself; the house of representatives can impeach him: They can remove him if found guilty: They can suspend him when suspected, and the power will devolve on the vice-president.150

Consistent with this evidence, most impeachment scholars in the United States have argued that the substantive standard reaches beyond crimes, although there are debates over exactly how broad the standard is.151 Scholars tend to conclude, consistent with that sense of the original understanding, that impeachable offenses must be “abuses against the state” that are analogous, in injury and intention, to those that concerned the Founders.152

But in the practice of impeachment, original understanding has not been destiny. Professor Griffin’s examination of the historical record of presidential impeachments shows that “the historical reality of the Johnson, Nixon, and Clinton impeachments is quite different.”153 Rather than hewing to the broader “Hamiltonian” reading of impeachment, as Griffin calls it, presidents and their supporters have since the early nineteenth century articulated an unsurprisingly narrower alternative—and have largely prevailed. On this more constrained view, presidents could be impeached “only for committing indictable crimes, or at least significant violations of law.”154 As noted in the Introduction, debates during the Trump impeachment reflected and deepened this conflation between serious crime and impeachment.

During the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, for example, “Congress wanted to impeach Johnson for abusing his constitutional powers to obstruct the enforcement of federal laws.”155 But the actual process centered mostly around Johnson’s supposed violation of the Tenure in Office Act by dismissing Edward Stanton from his post as Secretary of War.156 Since this was not really a crime in any conventional sense, but rather something more akin to an abuse of power, the tension between different models of impeachment was apparent. In contrast, during the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, the House of Representatives seemed to proceed under a more legalistic conception of the impeachment power. Three of the charges formulated by the House spoke directly to alleged crimes committed by Clinton: two counts of perjury and obstruction of justice. Two of these three counts passed the House and formed the basis on which Clinton was impeached; the third narrowly failed. In contrast, a single count of abuse of power failed overwhelmingly in a 148–285 vote.157 Similarly, during the weeks leading up the impeachment vote of Donald Trump, many possible charges were put forward, but the final charges were two: abuse of power and obstruction of Congress. The abuse of power count was criticized by Trump’s team as legally deficient on the grounds that it did not allege the violation of clearly established law, and particularly of a crime.158

Another reason for the dominance of a narrow, criminally focused understanding of impeachment (one not stressed by Griffin) may be the manner in which the text is formulated. The Constitution is normally read to create a unified impeachment standard that includes judges, high political officials, and chief executives.159 Removing only bad actors, essentially convicted criminals, makes good sense in the removal of judges as a way to protect judicial independence. Yet the same standard applied to chief executives may inhibit impeachment from facilitating exit during political crises, or at least may force actors to make disingenuous statements during impeachment processes. If so, this would be an example of drafting choices having unanticipated, even pernicious, effects on major elements of constitutional operation—a point to which we return in Part III.

Apart from the question of impeachment’s substantive threshold, the law and the historical record are sparse. Since the Founding, there have been many resolutions of impeachment brought against federal officials. Twenty were formally impeached in the House of Representatives.160 Of these, fifteen were federal judges, one was a senator, one a cabinet member, and three—Andrew Johnson in 1868, Bill Clinton in 1999, and Donald Trump in 2019—were sitting presidents.161 Of these, eight were convicted after a trial in the Senate, and removed from office. No chief executive has ever been removed from power following a Senate trial. The Clinton impeachment failed to achieve the requisite two-thirds vote by a significant margin; the Johnson removal failed by a single vote, 35–19; and Trump was acquitted by a vote of 48 in favor of conviction and 52 against on the closest charge, abuse of power.162

The difficulty, and resulting infrequency, of impeachment generates a perhaps troubling dynamic: it elicits a surfeit of impeachment talk, and arguably improper invocations of the procedure. Because impeachment attempts require a supermajority of two-third of senators for removal, there is a moral hazard dynamic inducing individual members in the House to introduce resolutions of impeachment. Members can claim credit without having to take responsibility for the subsequent costs of an impeachment that will almost certainly not proceed. As a result, almost every president has faced an effort by members of Congress to use impeachment as a way to paint them as a bad actor. In particular, in an increasingly polarized era, motions of impeachment have become somewhat routine, even if the process has rarely advanced beyond the stage of introduction. (In the post-Watergate era, President Jimmy Carter is the only president not to have had such a motion introduced.) The Clinton impeachment, in fact, was marred by such problems. Republicans wielded the report of special counsel Kenneth Starr as a way to paint Clinton as a bad actor. The crux of the debate focused on whether the acts that Clinton was accused of (essentially, lying under oath as part of a civil case about his sexual conduct) were sufficient to warrant impeachment. What got lost in this focus on the conduct of one man were broader issues of political context: Republicans controlled the House and thus were able to push through articles of impeachment, but they had nowhere close to the two-thirds majority in the Senate needed to remove Clinton from office without substantial Democratic party votes. The prospect of Democrats turning on Clinton was remote, given that his popularity remained high throughout the impeachment process.

Beyond this, one of the most striking regularities of historical practice in the United States is the absence—especially notable in comparison to the South Korean, Brazilian, and South African examples—of any real role for the courts.163 The Supreme Court has identified impeachment as the quintessential political question that precludes virtually all judicial review.164 The Court has found issues related to impeachment nonjusticiable, mostly because the text of the Constitution committed them “sole[ly]” to the two houses of Congress.165 Since no constitutional text clearly prohibits the Court from supervising legislative action in this area, this decision is perhaps better explained by pragmatic factors, such as the chaos that could ensue if there was a constitutional challenge to the removal of the president, and by the difficulty of crafting standards to figure out what terms like “try” mean in the context of an impeachment. One implication of this relatively light judicial touch is that there has been no “overlegalization” of impeachment procedure. This at least leaves open the possibility of impeachment being deployed as a way of removing a deeply unpopular leader.

In summary, impeachment in the U.S. context is marked by the gap between original expectations and incentive-compatible practice. Instead of a serious tool of accountability to remove a president in moments of systemic risk, impeachment talk has become an instrument of political harassment. On one view, therefore, it is possible to characterize the U.S. system of impeachment as marked by the worst of both worlds—an ineffective tool that nonetheless has become highly politicized.

F. Conclusion

Except for the United States—where the impeachment of chief executives has largely fallen into desuetude beyond the context of partisan cheap talk—there is a tight connection between removal mechanisms for chief executives and the presence of a crisis of popularity. Where both political elites and the public perceive a regime as unable to operate effectively (for whatever reason), they are inclined to support removal. Removal in the global context is not a matter of individual malfeasance. Rather, these case studies suggest, impeachment can additionally work as a systemic means of political reset triggered in moments of deep confidence crises among the public. Whether this conclusion can be sustained by a broader consideration of large-N comparative evidence is the question to which we turn next.

II. The Dynamics of Impeachment in Global Perspective

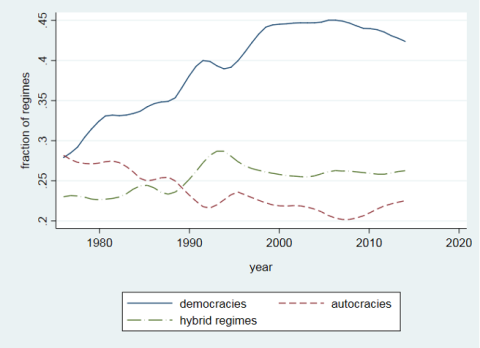

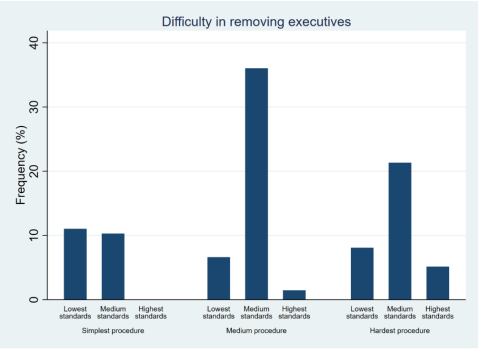

The case studies presented in Part I suggest that the term “impeachment” is in practice a catchall for a range of different practices. In this Part, we ask how frequently one observes different substantive and procedural versions of impeachment across different jurisdictions in different periods. As noted in the Introduction, we focus on the removal of fixed-term presidents. The most important examples of these are in presidential systems like the United States, where a chief executive who selects the government and has at least some constitutional lawmaking authority is selected by direct elections and survives for a fixed term of years,166 or in semi-presidential systems like France, where a fixed-term president coexists with a prime minister and both figures may have substantial power.167 But some parliamentary systems (such as Austria) also have fixed-term presidents who serve as heads of state with no real governmental power; we include impeachment of these figures as well in our dataset, though the cases are rare. In appropriate instances, we provide separate statistics for subsets, such as presidential and semi-presidential systems. We draw many of the statistics and analyses that follow from the Comparative Constitutions Project, a comprehensive inventory of the provisions of written constitutions for all independent states between 1789 and 2006, with data updated through 2017.168

A. Impeachment from Text to Practice

It is very common for democratic constitutions to provide for removal of the head of state under some conditions. As of 2017, 90% of presidential and semi-presidential regimes had constitutional rules that laid out a process for removal, either for incompetence, criminal action or some other basis.169 The procedures differ widely on such issues as the basis for dismissal, the process of proposal for dismissal, the process of approval, the period of the term of office within which the president’s mandate can be revoked, and the various timing of different steps. But they are matters of constitutional text, not of statutory enactment. Yet as the case of Brazil shows, the fact of constitutional entrenchment does not necessarily preclude the enactment of statutes with important effects on the process.170 We focus here, however, mainly on constitutional text. As a result, due caution should be exercised in drawing inferences about how that text interacts with statutory supplements or institutional cultures. In this Section, we first provide some basic empirics about the frequency of impeachment, and then lay out some examples of the range of provisions.

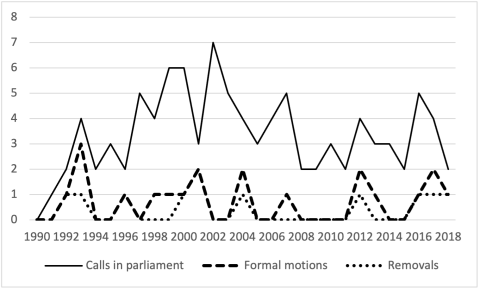

The ubiquity of constitutional text on impeachment is matched by a similar pervasiveness of attempts to remove presidents. Although attempts are not rare, they are rarely successful. One scholar, Professor Young Hun Kim, notes that some 45% of new presidential democracies faced an impeachment attempt in the period 1974–2003, and that nearly a quarter of presidents who served in this period were subjected to an attempt.171 Such attempts can vary in seriousness, ranging from mere calls by some set of legislators for impeachment to full formal votes in the parliament. Defined as a mere proposal in the legislature (that is, the first two rows of Table 1), attempts are exceedingly common. Supplementing Kim’s data, we gathered data on all such attempts between 1990 and 2018, and found at least 210 proposals in 61 countries, against 128 different heads of state. Using Kim’s fourfold framework for level of attempt, we identified the highest level of seriousness in each attempt, and report these in Table 1. We add the first two rows to get the total number of proposals, though acknowledge there is some difficulty distinguishing different attempts.

|

Level |

1990–1999 |

2000– 2009 |

2010–2018 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 = proposal by some deputies to impeach |

34 |

80 |

30 |

144 |

|

2 = unsuccessful attempt to place the question on the parliamentary agenda |

22 |

37 |

10 |

69 |

|

3 = parliament votes on impeachment but motion fails |

3 |

11 |

6 |

20 |

|

4 = parliament passes an impeachment vote |

8 |

8 |

6 |

22 |

|

Head of state leaves office before process complete172 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

9 |

|

Removal through impeachment |

3 |

4 |

3 |

10 |

These attempts are not uniformly distributed. Impeachment is quite common in some countries: Ukraine, for example, has featured 25 different proposals in the 28-year period we examine. Other countries with frequent calls include Nigeria (17), South Korea (13), Ecuador (10), the Philippines (9), and Brazil (10). Russia had 13 attempts in the tumultuous 1990s, but none since President Vladimir Putin came to power. These are countries, one might speculate, where ordinary processes of political bargaining have broken down, leading parties to escalate quickly to the ultimate weapon in the political arsenal. Preliminary evidence also indicates that such motions become more likely after the first deployment.

As the last row in Table 1 demonstrates, successful removal by impeachment is a rarity. We identify a total of 10 cases since 1990, listed in Table 2 below.173 Close inspection of these cases suggests that successful removal typically involves a situation in which the opposition has control of the parliament and is also able to convince some members of the president’s party to defect. Both attempts and removals are more frequent when the president is unpopular and does not have a majority of support in the legislature. They often occur in the context of structural shifts in the larger party system.174

Convincing a president’s copartisans to defect is difficult. Presidential systems are characterized by single individuals who enjoy popular appeal but may not necessarily have strong roles within their own parties.175 Party leaders may have a good deal of trouble controlling their presidential candidate once in office (and so the occasionally rocky relations between President Trump and congressional leaders of the Republican Party are less atypical than one might expect). While one might assume that this would lead to parties turning against their presidents on occasion, the linked electoral fates of parties in the legislative and executive branches mean that they have relatively weak incentives to do so (even if they do control the levers of impeachment or removal).176 At the very least, to impeach one’s own party leader implies that the party was incompetent in choosing the person as a candidate. Worse, it might catalyze a fragmentation of the party, as the spurned leader breaks off with his or her own political coalition.

To illustrate why it is that removing presidents is so hard even when their party turns against them, consider the attempt to dismiss President Ranasinghe Premadasa of Sri Lanka. In 1991, a motion to impeach Premadasa was raised in the Parliament, and was supported by some members of his own party.177 Premadasa was able to expel dissident members from the party, which meant, in accordance with the text of the Sri Lankan Constitution, that they lost their seats in Parliament. Other instances of failed attempts in presidential systems to use impeachment for intraparty conflict include the case of South Korea’s Roh Moo-hyun, as discussed above in Part I.A. Recall that Roh was impeached after a split in his party, but not removed by the country’s Constitutional Court, as it found that the violations were insufficiently severe to justify a removal from office.178 Again, because Roh maintained public support, and his party was faring well at the polls, there was a close alignment of interests between chief executive and party. Under those circumstances, impeachment will rarely occur.

In the context of pure presidential systems, we have been able to locate one case of a party’s legislative majority voting to remove its own president. That was President Raúl Cubas Grau in Paraguay in 1999, who resigned after his impeachment by the Chamber of Deputies and just before a Senate vote that would have completed his removal from office.179 Cubas had won the party’s nomination only because the party leader had been jailed for a coup attempt. After a political assassination, another faction in his party attempted to impeach him in favor of its preferred candidate. This was successful after a period of political turmoil. Professors David Samuels and Matthew Shugart attribute the successful removal to a rare instance in which the party in question truly dominates the political scene and all levers of power.180 Intraparty fights thus substitute for the party-against-party competition that typically characterizes general elections.

At the same time, it is sometimes the case that a handful of members of a president’s party will join with others in an impeachment motion or threat. Such was the case when Richard Nixon resigned under threat of impeachment in 1974. Other examples involving impeachment or related mechanisms include Ecuador’s President Abdalá Bucaram in 1997 and President Jamil Mahuad in 2000, Venezuela’s President Carlos Andrés Pérez in 1993, and Guatemala’s President Otto Pérez Molina in 2015.181 In 2005, Ecuador’s Congress deposed President Lucio Gutiérrez from office for abandoning his duties, though it did not have to complete the impeachment process because of his resignation.182 In these cases, individual legislators’ interests plainly diverged from those of the party, perhaps because of differences in the consistencies represented by different legislators within the same party, or perhaps because of ideological divisions within the party.

Table 2 presents all the cases of successful removal of directly elected presidents through impeachment since 1990. It shows that the phenomenon is not unknown. But it is also not particularly common. It represents well less than half of 1% of all country-years in which impeachment might have occurred. The final column of Table 2 also offers a threshold piece of evidence of the impact of impeachment on the political system. It does so by tracking whether the country’s level of democracy improves or declines as a result of impeachment. To measure democracy, we use the widely utilized Polity2 index, which rates democratic quality on a 21-point scale ranging from –10 (total autocracy) to +10 (total democracy). By convention, scores of 6 or higher are considered full democracies. In the column on the far right, we track the change in the Polity2 rating from two years prior to impeachment to two years after.

|

Country |

Year |

President |

Polity Score Two Years |

Polity Score Two Years |

Change in Polity Score from t-2 to t+2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brazil |

1992 |

Fernando |

8 |

8 |

0 |

|

Venezuela |

1993 |

Carlos Andres Pérez184 |

9 |

8 |

-1 |

|

Madagascar |

1996 |

Albert Zafy |

9 |

7 |

-2 |

|

Peru |

2000 |

Alberto |

1 |

9 |

+8 |

|

Philippines |

2001 |

Joseph |

8 |

8 |

0 |

|

Indonesia |

2001 |

Abdurrahman Wahid |

6 |

6 |

0 |

|

Lithuania |

2004 |

Rolandas Paksas186 |

10 |

10 |

0 |

|

Paraguay |

2012 |

Fernando |

8 |

9 |

+1 |

|

Brazil |

2016 |

Dilma Rouseff |

8 |

8 |

0 |

|

South |

2017 |

Park |

8 |

8187 |

0 |

It is first worth noting that every country that successfully impeached a president remained a full democracy thereafter, in most cases without any change in the level of democracy. Even Madagascar, where President Albert Zafy was impeached in 1996, was still a full democracy a few years later. Peru’s impeachment of President Alberto Fujimori occurred as part of the restoration of democracy after his period of autocratic rule, and hence we see a significant positive jump in that case.

To this list could be added several instances in which impeachment occurred but the president was not removed, either because he or she was not convicted or because of extraconstitutional action. Of course, U.S. Presidents Bill Clinton and Donald Trump were examples of the former. Russian President Boris Yeltsin was impeached in the early 1990s but dissolved Parliament to stay in office.188 Similarly, Alberto Fujimori’s “self-coup” in 1992 was followed by a vote to remove him, but Fujimori had already dissolved Congress.189 Only the Russian case, which occurred when Russia could be characterized as a semidemocracy in the midst of a tenuous (and ultimately failed) transition from authoritarianism, led to a significant decline in the Polity score. Finally, we note that the ultimate results of the Brazilian case are still ambiguous: although Temer’s rocky tenure was followed by a competitive election, it remains to be seen whether, or to what extent, Jair Bolsonaro damages Brazil’s democratic structure.190 Early signs suggest that he may be effectively constrained by the legislature from implementing his most authoritarian plans, and his coronavirus strategy of denial has generated significant institutional pushback.191