An Empirical Analysis of Sexual Orientation Discrimination

This study is the first to empirically demonstrate widespread discrimination across the United States based on perceived sexual orientation, sex, and race in mortgage lending. Our analysis of over five million mortgage applications reveals that any Fair Housing Administration (FHA) loan application filed by same-sex male co-applicants is significantly less likely to be approved compared to the white heterosexual baseline (holding lending risk constant). The most likely explanation for this pattern is sexual orientation–based discrimination—despite the fact that FHA loans are the only type of loan in which discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is prohibited.

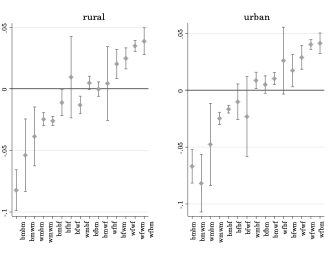

Moreover, we find compelling evidence to support the intersectionality theory. According to this theory, when sex and race unite, a new form of discrimination emerges that cannot be explained by sexism or racism alone. The data unequivocally indicates that the race and sex of same-sex applicants play a role and result in a unique and previously unobserved pattern. This discriminatory pattern plagues every region in the United States, and it transcends party lines (that is, it is present in red, blue, and swing states). Furthermore, upending conventional wisdom, the data reveals that big banks discriminate at the same rate as small banks, and lenders in urban environments are as discriminatory as rural lenders. Prior studies failed to reveal this phenomenon due to data constraints and design flaws. These studies relied on testers posing as applicants, and none could investigate how intersectionality influences lending practices.

Despite the grim results, a silver lining exists. We find that the pattern of discrimination diminishes or disappears in states and localities that pass anti–sexual orientation discrimination laws. These findings have important and timely implications. In 2017, a new bill offering nationwide protection from sexual orientation credit discrimination was introduced. The same year experienced tectonic changes in Title VII jurisprudence. Our study can reinvigorate the debate and help policymakers tailor remedies that would correct the discriminatory pattern this study unravels.

Introduction

Twenty years ago, a gay couple entered their local bank in Arroyo Grande, California to ask for a mortgage loan. Excited, they filled out the application. But the festive event took a surprising turn. The couple was quickly asked to leave and even close their existing accounts. “It was bank policy,” so they learned, “not to offer home loans to gay applicants.”1

While recent years brought more legal protections2 to members of the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB3 ) community, our data suggests that they should not expect to be treated equally. This should not come as a surprise. Federal law and the majority of states do not prohibit lenders from discriminating against applicants based on their sexual orientation. Simply put, when it comes to mortgage lending, sexual orientation discrimination is the rule.

Not only is explicit sexual orientation discrimination permitted; it can be used by lenders as a “defense.”4 This defense is often raised when the mortgage applicant belongs to a protected group. For example, a lender who discriminated against a black applicant could escape liability if it shows that the source of discrimination was not the applicant’s race (a protected characteristic that gives rise to liability) but his sexual orientation. To be blunt, the bank can claim, “I discriminated against the applicant not because he was black, but because he was gay.”5

There are a few exceptions. A small (but growing) number of states now prohibit sexual orientation discrimination in mortgage lending.6 Even in states where such discrimination is permissible, some strongholds exist: certain localities decided to prohibit what federal law and their state allow. For example, Michigan does not prohibit sexual orientation discrimination in mortgage lending, but the city of Ann Arbor does.7 The same is true for Atlanta, the only municipality in Georgia to protect LGB individuals.8 By contrast, two states, Arkansas and Tennessee, prohibit any local legislation that would protect against sexual orientation discrimination.9 In these states, the ability to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation is protected by statute. Finally, lenders of mortgages insured by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), known as “FHA loans,” are not allowed to discriminate based on sexual orientation.10 But as the data reveals, sexual orientation discrimination—even in FHA loans—not only exists but is prevalent.

In what follows, we present the first econometric evidence of widespread bias in mortgage lending on the basis of perceived sexual orientation. Using data provided by the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act11 (HMDA), we evaluate the probability of home loan acceptance for virtually every FHA loan between the years 2010 and 2015. The dataset is unique in a number of respects. First, it is large, containing more than five million observations. This allows us to show that the discrimination is widespread, statistically significant, and robust. Second, the dataset is rich enough to allow us to estimate acceptance rates for perceived LGB couples of all gender and racial compositions (for example, applications filed by two black males, two white males, a white male and a black male, two black females, etc.). Lastly, it has a geographical level of granularity that allows us to examine small geographic areas—down to a neighborhood level.

The results are alarming. We find that same-sex male co-applicants (or pairs) are between 2.5 and 7.5 percentage points less likely to have their loan application accepted compared to the white heterosexual baseline.12 This is true despite the fact that the same-sex male pairs were identical in all reported respects to the heterosexual baseline. That is, same-sex male pairs filed a mortgage application with the same lender, in the same county, for the same loan amount, for the same purpose, had the same income, and posed the same level of risk to the lender. Nevertheless, discrimination rules. The results are statistically significant at the 99 percent level.

Moreover, we find compelling evidence to support the intersectionality theory.13 According to this theory, when sex and race unite, a new form of discrimination emerges that cannot be explained by sexism or racism alone. The data unequivocally indicates that, in addition to sex and sexual orientation, race also plays a significant role. The result is a unique and previously unobserved pattern. Although applications of all same-sex male pairs are less likely to be accepted, male pairs with black applicants are substantially worse off. From most to least discriminated groups are (i) pairs consisting of two black males (denoted black male/black male), followed by (ii) interracial pairs in which the black male is the primary applicant and the white male is the secondary applicant, then (iii) interracial pairs in which the white male is the primary applicant and the black male is the secondary, and finally (iv) white male pairs. The differences are significant. An application filed by a pair of two black males is three times less likely to be accepted compared to an application filed by a pair of two white males, and both pairs face discrimination compared to the heterosexual baseline.

Consistent with the social science literature, the data suggests that perceived gay male couples are treated differently than perceived lesbian couples.14 While every possible racial combination of same-sex male co-applicants is statistically disadvantaged, the treatment of same-sex female co-applicants is either indistinguishable or preferable compared to the white heterosexual baseline couple. Interestingly, however, we observe the exact same racial pattern as in the male pairs: within the female pair group, a pair of two black females is the least likely to be approved, followed by interracial pairs of black female/white female, then white female/black female pairs, and finally white female pairs.

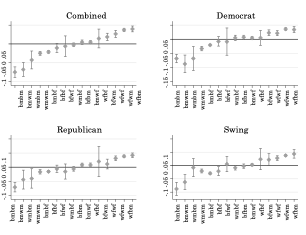

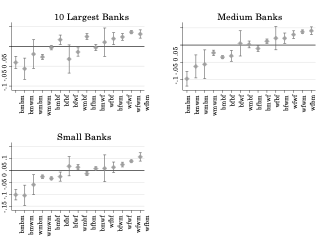

This pattern of discrimination is not isolated to a specific geographical region or political ideology. Rather, we find evidence that this form of discrimination transcends geographical and political borders. In all four regions in the United States, applications of same-sex male pairs are less likely to be accepted compared to the baseline white heterosexual pairs (although in certain cases, the results are statistically insignificant).15 Interestingly, we find that interracial male co-applicants (that is, white/black and black/white) face the most discrimination in the Northeast. Their applications are 12.2 percentage points less likely to be accepted compared to the baseline (the results are statistically significant at the 99 percent level). Splitting the data by political affiliation does not change the results in a meaningful way. It reveals that Democratic states are as discriminatory as Republican states overall and, in fact, are the least tolerant of interracial male pairs. The same trend also holds irrespective of the size of the lender. That is, big lenders discriminate in the same way as small banks. Using a difference-in-differences framework, we do find, however, that efforts by states and localities to pass laws prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination tend to be successful in discouraging sexual orientation discrimination.

The Article contributes to the economic and empirical research in a number of ways. First, it highlights a new dimension of discrimination that has been previously ignored. Surprisingly, of the very few studies that attempted to explore sexual orientation discrimination, to date only two studies focused on mortgage lending. The first study compared the treatment of testers posing as heterosexual couples with testers posing as same-sex couples with better credentials.16 The second study was also empirical in nature.17 However, both studies suffered from limitations.18 Most importantly, their design did not allow the researchers to test how the intersectionality of race, sex, and sexual orientation influences home lending practices.19 For example, the studies could not analyze whether black and white couples are treated differently or whether black female couples are treated differently than white female couples. They overlooked the existence and magnitude of intersectional discrimination and were unable to reveal the patterns we observe here. Second, our study is also the first to measure the presence and magnitude of sexual orientation discrimination regarding mortgages that are subject to the Equal Access Rule20 —the only type of mortgage in which discrimination based on sexual orientation is prohibited nationwide. Third, our study indicates that the prior literature may have underestimated the magnitude of sexual orientation discrimination. The reason for this is the failure of these studies to distinguish between same-sex male couples and same-sex female couples. The data suggests that the second group—female couples—is treated as well or more favorably compared to male couples and even compared to the heterosexual baseline. Thus, studies that treated LGB individuals as one homogenous group likely underestimated the discrimination faced by gay males. Fourth, ours is the only study to address the efficacy of state and local laws designed to discourage sexual orientation–based discrimination.

Our study also suggests that the observed discrimination is not motivated by lenders’ attempts to assess the risk associated with the applicants by segmenting the market. Rather, because we compare applications with the same level of risk to the lender,21 it is more likely that the discrimination is motivated by bigotry (conscious or otherwise). The distinction is important. To eliminate discrimination, policymakers—legislators and regulators—must know the motivating force.

Our study is timely. In May 2017, a new bill was introduced offering nationwide protection from discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation to those seeking credit.22 In the same year, Title VII jurisprudence experienced a tectonic change when the Seventh Circuit held, for the first time, that sexual orientation discrimination is prohibited under Title VII.23 A month later, the same holding was adopted by a federal court in the Southern District of New York;24 and by April 2018, the First Circuit25 and Second Circuit26 joined what now seems like a trend.27 Our study can help reinvigorate the debate and help policymakers tailor remedies that would correct the discriminatory pattern that this study unravels.

The rest of the Article continues as follows: Part I first outlines the law and reveals the perverse results of the sexual orientation discrimination defense. It then discusses two important forms of discriminatory practices and how two common remedies—which we later test—may affect these practices. Part I.C then turns to review the prior studies and their shortcomings. Part II discusses the study’s methodology and the results. The Article then provides concluding remarks.

I. Sexual Orientation and the Law

A. Federal Law

The two main federal statutes prohibiting discrimination in mortgage lending are the Fair Housing Act28 (FH Act) and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act29 (ECOA). The first focuses on residential real estate transactions, while the second focuses more broadly on any credit transaction. Together, they make it unlawful for any lender to discriminate against a protected applicant by denying a mortgage or providing unfavorable terms or conditions.30 The federal statutes, however, are limited in scope: they prohibit discriminatory lending practices if they are based on race, color, religion, national origin, or sex.31 Although the ECOA and FH Act include other bases for discrimination,32 neither protects against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.33 The result is that lenders can discriminate against LGB individuals (or those perceived as such) with impunity. There are, however, a few exceptions.

1. Discrimination against a protected class.

Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation may be illegal if it also violates the prohibition against discrimination against a protected class. An example is declining to give a mortgage to a gay applicant for fear of contracting HIV.34 Such behavior is illegal discrimination on the basis of disability—a protected characteristic under the FH Act.35 This protection includes not only actual physical impairment but also “being regarded as having such an impairment.”36

Similarly, courts have interpreted the prohibition against sex discrimination broadly to include discrimination based on gender identity or perceived gender nonconformity.37 As a result, the ECOA and FH Act now afford protection to transgender applicants and, under certain circumstances, to LGB individuals.38 The leading precedent is Price Waterhouse v Hopkins,39 a Title VII decision. Price Waterhouse involved a female plaintiff whose candidacy for partnership was put on hold. It was clear that her gender played a role in the employer’s decision.40 In addition to legitimate criticism, some of the plaintiff’s colleagues described her as “macho” and advised her to take a “course at charm school.”41 The head of her office—her biggest supporter42 —was more explicit. He advised the plaintiff that, to improve her chances, she “should ‘walk more femininely, talk more femininely, dress more femininely, wear make-up, have her hair styled, and wear jewelry.’”43 In a plurality opinion, the Supreme Court held that discrimination on the basis of gender-based stereotypes constitutes illegal sex discrimination.44 The decision was later construed as also protecting transgender plaintiffs. As the Sixth Circuit explained, if discriminating against women who do not wear dresses constitutes sex discrimination, “[i]t follows that employers who discriminate against men because they do wear dresses and makeup, or otherwise act femininely, are also engaging in sex discrimination.”45

Price Waterhouse’s holding and its progeny were adopted in the mortgage lending context.46 But even after Price Waterhouse, sexual orientation remains an unprotected characteristic.47 Still, as in the case of disability, discrimination against LGB individuals may be illegal if it is based on perceived nonconformity with gender stereotypes (a protected characteristic post–Price Waterhouse). This means that a gay male applicant who was wearing women’s clothing would have a valid cause of action if his application was denied because the loan officer thought he did not meet stereotyped expectations of masculinity.48 If, however, the lender could show that sexual orientation was the sole reason for the discrimination—that is, the applicant was discriminated against because the loan officer believed he was gay—the plaintiff’s suit would fail.49 Put differently, the LGB plaintiff cannot simply argue that she was discriminated against because of her sexual orientation. Rather, she needs to show that the discrimination was based on a protected basis like sex stereotyping. As Part I.B demonstrates, however, such a showing is often impossible.

2. Agencies’ interpretations and regulatory enforcement.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB)—the agency responsible for enforcing and administering the ECOA50 —has taken a broader view than the federal courts. Contrary to Price Waterhouse, the CFPB’s director opined in a letter issued in 2016 that sexual orientation discrimination is a form of sex discrimination.51 The opinion relied on two grounds: (a) recent decisions issued by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC)52 and (b) the theory of discrimination by association. In the mortgage lending context, this theory prohibits a loan officer from denying an applicant based on her association with a person belonging to a protected class.53 For example, the doctrine prohibits a lender from discriminating against a white applicant whose spouse is black. The CFPB’s director took the stance that the same theory prohibits discrimination against applicants based on the sex of their partners and, therefore, prohibits sexual orientation discrimination.54 Despite the CFPB’s expansive view and its efforts to solicit complaints from consumers, it is unclear how active and effective the agency is in dealing with discriminatory practices.55

3. FHA mortgage insurance and the Equal Access Rule.

There is one category of loans in which sexual orientation discrimination is wholly prohibited and on which our study focuses: FHA-backed mortgages. The prohibition is articulated in the Equal Access Rule adopted in 2012 by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the agency responsible for administering the FH Act.56 The rule prohibits lenders of mortgages insured by the FHA (commonly referred to as FHA loans) from considering applicants’ actual or perceived sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status.57 This means that a lender would be in violation of the Equal Access Rule if it denied an FHA mortgage because the applicant was (or was believed to be) gay.58

The rule, however, is limited in scope and has—as our study shows—a limited effect. To begin with, FHA loans comprise a significant but still limited portion of the market. According to HUD’s Office of Risk Management and Regulatory Affairs, in 2017, FHA single-family home mortgage insurance measured by loan count was only 16.7 percent.59 That market share drops to 13.4 percent if measured by dollar volume.60 The upshot is that the majority of mortgage loans are not subject to the Equal Access Rule.

Moreover, the rule does not provide applicants with a private cause of action.61 As a result, the sole remedy available to applicants who believe the rule was violated is to complain to HUD.62 Few complaints, however, are filed and processed every year, and even fewer result in a charge of discrimination.63

B. Sexual Orientation Discrimination as a Defense

Not only is sexual orientation discrimination permissible, but it can also serve as a “defense” in jurisdictions that have not followed Hively v Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana64 and Zarda v Altitude Express, Inc.65 The reason is the law of causation. In a discrimination case, the plaintiff has to show that the lender considered an illegitimate motive (for example, the applicant’s race). In addition, the plaintiff must prove that the illegitimate motive was the cause of the discriminatory decision.66 Despite burden-shifting frameworks,67 meeting the causation requirement is not easy. For members of the LGB community, it may be impossible.68

To illustrate, consider a black male with perfect credit whose application was refused. Suppose also that he came to the lender dressed in what some would consider feminine attire.69 Here, the basis for the discriminatory action is unclear. It could be that the applicant was discriminated against because of his sex (male), his race (black), or his perceived gender identity (failing to meet stereotyped expectations of masculinity as a cross-dresser). In any of these cases, the applicant has a valid cause of action, but the lender may have a defense. It could be argued that the discrimination was based on the applicant’s actual or perceived sexual orientation (being gay or perceived as gay). Here, the question of the lender’s motive is paramount. If the sole reason for denying the application was an illegal consideration—for example, the male applicant’s effeminate dressing style—the plaintiff would prevail.70 In such a case, the denial is considered impermissible sex discrimination because it is based on the applicant’s nonconformity with sex stereotypes. By contrast, if the sole motivation for rejecting the application is the loan officer’s belief that the applicant is gay, the consideration is deemed “legitimate” and permissible.71 Finally, suppose that the loan officer’s motivation was “based on a mixture of legitimate and illegitimate considerations.”72 In these cases, the lender can still avoid paying damages if it proves that the legitimate motive alone (for example, denying the application because the applicant was perceived as gay) would have led it to make the same decision (that is, denying the application).73

If this sounds too fantastic, consider Rosa v Park West Bank and Trust.74 In Rosa, a bank employee refused to give the plaintiff (Rosa), a transgender individual wearing “traditionally female attire,” a loan application unless he “went home and changed.”75 Rosa brought an ECOA suit against the bank, claiming that the requirement to conform to gender stereotypes was a form of sex discrimination. The district court granted the bank’s motion to dismiss.76 Relying on Title VII jurisprudence and Price Waterhouse, the First Circuit reversed.77 It held that Rosa had a valid cause of action if the bank treated “a woman who dresses like a man differently than a man who dresses like a woman.”78 Such disparate treatment based on gender stereotyping would be considered discrimination on a prohibited basis: sex. By contrast, if the loan officer refused Rosa because the loan officer thought Rosa was gay, Rosa would have no federal cause of action.79 The ECOA—like the FH Act and other titles of the Civil Rights Act—does not prohibit sexual orientation discrimination.80

The sexual orientation defense carries a number of perverse consequences. First, it may help explain why discriminatory incidents are under-reported. The reason is that the defense allows defendants to put the sexual orientation of the plaintiff on trial—even when the plaintiff’s case relies solely on protected bases and even if the plaintiff is not a member of the LGBT81 community. For example, the black plaintiff who sues a lender for racial discrimination may worry that she will need to defend herself against the claim that her perceived sexual orientation was the real reason for the discrimination. As a result, plaintiffs who have a valid cause of action may avoid litigating in the first place. This is true for all types of victims, including heterosexual applicants who belong to a protected class.

Second, LGB individuals who do not feel comfortable disclosing their sexual orientation may avoid filing discrimination suits for fear that they will be outed or simply because they do not feel comfortable putting their sexual orientation on trial.

Third, LGB individuals who are willing to disclose (or avoid hiding) their sexual orientation should think twice. If they do disclose their sexual orientation, they increase the risk that a court will treat their sex stereotyping claims as masking meritless sexual orientation allegations. Dawson v Bumble & Bumble,82 a case involving an openly lesbian employee, is such an example. The court was concerned that the plaintiff was merely trying to use a gender stereotyping claim to “bootstrap protection for sexual orientation into [the statute].”83 It explained that “[w]hen utilized by an avowedly homosexual plaintiff [ ] gender stereotyping claims can easily present problems for an adjudicator.”84 The Dawson court solved the “problem”—a suit filed by a LGB plaintiff—by dismissing the case. By contrast, in Centola v Potter85 the plaintiff “never disclosed his sexual orientation to anyone at work.”86 Based on this repeated and much-emphasized fact,87 the court concluded that the discrimination suffered by the Centola plaintiff was likely based on gender stereotypes. This conclusion led the court to reject the defendant’s motion for summary judgment.88

Dawson and Centola highlight a real concern. In many cases, it is impossible to separate sexual orientation discrimination claims from sex stereotyping claims. Recognizing this difficulty, courts often refer to the line between sexual orientation and sex stereotypes as one that is “hardly clear,”89 “difficult to draw,”90 one that “does not exist,”91 and is “illogical and artificial.”92 “[S]tereotypes about homosexuality,” they explain, are simply too “related to our stereotypes about the proper roles of men and women.”93 This difficulty has led many courts to outright reject gender stereotyping discrimination claims for fear that they are framed to mask a sexual orientation discrimination claim.94 Dawson was recently overruled by Zarda, which extended Title VII protections to victims of sexual orientation discrimination, but its reasoning may apply in jurisdictions that have yet to join or have rejected the trend. In such jurisdictions, the teaching of cases like Dawson and Centola is that LGB applicants who want to avoid that fate should hide their true sexual orientation. The concern is broader. Because the test focuses on “perceived” sexual orientation, all applicants might have the incentive to conform to societal expectations concerning gender stereotypes.

By contrast, LGB applicants whose sexual orientation is known to the loan officer may be pressured to adopt mannerisms stereotypically associated with the opposite sex (for example, a homosexual male may want to wear women’s clothing or act femininely). If they do not, they run the risk that any future claim of discrimination will be easily dismissed (because sexual orientation discrimination is permissible while gender stereotyping discrimination is not).

To see this, consider the following example: A married gay male with a perfect credit score enters a bank and fills out a mortgage application. The loan officer is aware of the fact that the applicant is gay—perhaps because the applicant submitted a marriage certificate during the application process. Based solely on the applicant’s sexual orientation, the loan officer rejects the application.

If the gay male applicant appears to be stereotypically masculine, he may have a hard time showing that he was discriminated against on the basis of a protected characteristic. By contrast, a gay male who fails to conform to stereotypes associated with his gender (for example, if he wears women’s clothing or appears to be effeminate) will likely have an easier time stating a prima facie claim. The reason is that “cases applying Price Waterhouse have interpreted it as applying where gender non-conformance is demonstrable through the plaintiff’s appearance or behavior.”95 Thus, unless the plaintiff can prove that “his appearance or mannerisms . . . were perceived as gender non-conforming in some way,” his action is destined to fail.96 In the above example, the applicant’s case is more likely to succeed if he wears what is considered women’s clothing even if he prefers not to. Behaving in such a gender nonconforming manner against one’s natural tendencies, however demeaning and ludicrous, has another strategic benefit. It shifts the burden to the defendant to show that its motive was based solely on the applicant’s perceived sexual orientation.

Another perverse outcome—a slight variant of the one described immediately above—relates to the role of gender-based stereotypes. Under Price Waterhouse, discrimination based on such stereotypes is illegal sex discrimination. As a result, discriminating against a woman who walks, talks, and dresses like a man is prohibited. But if a loan officer instead relies on such stereotypes to infer that the applicant is homosexual and then discriminates solely on the basis of homosexuality, the discrimination is not actionable in most jurisdictions.

To illustrate, consider again the male applicant with a perfect credit score whose application was denied because the loan officer believed he was gay, perhaps because the loan officer thought he seemed effeminate. If the lender cites the applicant’s (perceived) sexual orientation as the reason for denying the application and can prove that sexual orientation was the sole basis for the denial, the lender will not be liable for the discrimination. The sexual orientation discrimination defense, therefore, allows a loan officer to rely on gender stereotypes to inform the lender’s belief that the applicant is gay and then permissibly discriminate against that applicant because he appears gay, despite Price Waterhouse’s prohibition against discrimination based on gender stereotypes.

Finally, the sexual orientation defense likely dilutes the protection afforded to transgender applicants against gender identity discrimination. In cases in which the gender identity of the applicant visibly “transgresses gender stereotypes,”97 the lender may have an easier time raising the sexual orientation defense. As Dawson and Centola suggest, in these cases, transgender applicants are more likely to have their day in court if they hide their transgender identities. Thus, the law not only allows discrimination based on sexual orientation but also incentivizes applicants to hide their true gender identity or sexual orientation in some cases and misrepresent them in others.

In sum, with the exception of the Equal Access Rule, federal law does not prohibit sexual orientation discrimination when it comes to mortgage lending. Rather, it views sexual orientation as a “legitimate” (if abhorrent) basis for discrimination. The result may be under-reporting of all types of discriminatory incidents, more discrimination, and a myriad of perverse outcomes. Both the FH Act98 and ECOA,99 however, left the door open for state and local legislatures to provide broader protection. As the next Section explains, however, the majority of states and local jurisdictions have forgone the opportunity.

C. State and Local Laws

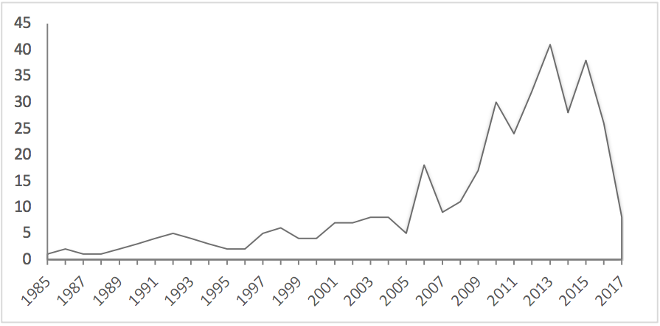

Although all states have enacted fair housing laws, only twenty-three states include a provision prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination in lending. Twenty of these states also prohibit gender identity discrimination. Table 1 lists the states that enacted fair housing laws prohibiting gender identity and/or sexual orientation discrimination, including the enactment and effective dates of the relevant statutes. Finally, two states, Arkansas and Tennessee, forbid their localities from adopting ordinances that would prohibit discrimination on a basis not recognized by the state.100 The result is that the same discriminatory behavior may be allowed in some states but not in others. Moreover, even in those states that do not prohibit discrimination in lending against members of the LGB community, discrimination may be prohibited in certain localities and counties. As Figure 1 below illustrates, the annual increase in the number of such political subdivisions sharply increased in 2010 and reached its highest point in 2013—the year following the enactment of the Equal Access Rule.

| Sexual Orientation | Gender Identity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Passed | Effective | Passed | Effective |

| CA | 10/10/1999 | 10/10/1999* | 09/06/2011 | 01/01/2012 |

| CO | 05/29/2008 | 05/29/2008 | 05/22/2014 | 08/06/2014 |

| CT | 05/01/1991 | 09/01/1993 | 07/01/2011 | 10/01/2011 |

| DE | 07/02/2009 | 07/02/2009 | 06/19/2013 | 06/19/2013 |

| DC | 12/13/1977 | 12/13/1977* | 12/22/2005 | 03/08/2006 |

| HI | 07/11/2005 | 07/11/2005 | 07/11/2005 | 07/11/2005 |

| IL | 01/21/2005 | 01/01/2006 | 01/21/2005 | 01/01/2006 |

| IA | 05/05/2007 | 05/05/2007 | 05/05/2007 | 05/05/2007 |

| ME | 03/28/2012 | 09/01/2012 | 03/28/2012 | 09/01/2012 |

| MD | 05/15/2001 | 01/01/2001 | 05/15/2014 | 10/01/2014 |

| MA | 11/15/1989 | 11/15/1989 | 11/23/2011 | 07/01/2012 |

| MN | 04/02/1993 | 04/02/1993 | 04/02/1993 | 04/02/1993 |

| NV | 06/01/2011 | 06/01/2011 | 06/01/2011 | 06/01/2011 |

| NJ | 01/19/1992 | 01/19/1992 | 12/19/2006 | 06/17/2007 |

| NM | 04/08/2003 | 07/01/2003 | 04/08/2003 | 07/01/2003 |

| OR | 05/09/2007 | 01/01/2008 | 05/09/2007 | 01/01/2008 |

| RI | 05/22/1995 | 05/22/1995 | 07/13/2001 | 07/13/2001 |

| UT | 03/12/2015 | 05/12/2015 | 03/12/2015 | 05/12/2015 |

| VT | 04/23/1992 | 04/23/1992* | 05/22/2007 | 07/01/2007 |

| WA | 01/31/2006 | 06/08/2006 | 01/31/2006 | 06/08/2006 |

| NH | 06/09/1997 | 01/01/1998 | - | - |

| NY | 12/17/2002 | 01/16/2003 | - | - |

| WI | 03/02/1981 | 03/02/1981* | - | - |

Figure 1: The Number of New Local-Level Protections against Sexual Orientation Discrimination in Jurisdictions without State-Level Protection102

D. An Under-studied Phenomenon

Of the very few studies that investigate sexual orientation discrimination, only two focus on the mortgage lending market.103 As we explain below, these studies were limited in nature. The first was a field experiment that was conducted in one state (Michigan), before the enactment of the Equal Access Rule, and had only 120 observations, of which only thirty-six focused on home financing.104 The second, written concurrently with this Article, was empirical in nature.105 This study treated all same-sex couples as one homogenous group, it focused on all mortgages (not just FHA loans), and it ignored the effect of state and local laws on acceptance rates. Importantly, due to their design, these studies could not provide—not even anecdotally—answers to the questions we investigate here. This Section begins with a short overview of the economics of discrimination. It then reviews the leading studies on sexual orientation discrimination and the shortcomings of their designs.

1. The economics of discrimination.

Discrimination in the home mortgage lending process is a topic that has received considerable attention both from academics and policymakers. In his seminal book, The Economics of Discrimination,106 Professor Gary Becker provided a basis for much of the theoretical work on discrimination.107 According to Becker, some individuals act as though they have a “taste,” or preference, for discrimination against a minority group.108 But discrimination comes at a cost: forgoing profitable transactions with members of the discriminated group.109

Theory predicts that in a competitive market, this cost will drive out taste-based discrimination.110 For example, an employer who prefers to hire only white employees forgoes the benefits that talented nonwhite employees may bring. Those employees may be hired by other firms and possibly at a lower than average salary. As a result, nondiscriminating firms may be able to offer better products or services at a lower price and consequently drive the discriminating firm out of the market.111 In the mortgage lending context, the cost of discriminating can also be prohibitive. Rejecting applicants with good credit because they belong to a certain group may result in fewer profits and a reduction in value. This is the case, for example, if the prejudicial lender reaches a point at which sales made to his preferred groups are exhausted. At that point, the prejudicial lender must either offer loans to all individuals or incur losses. Charging supracompetitive prices to members of a protected group (for example, reverse redlining112 ) is also infeasible if enough lenders are willing to offer credit.113 Markets, however, are not always competitive, and as a result, taste-based discrimination may persist.114

A different theory that explains why discrimination may persist in competitive markets, and can even be efficient, is statistical discrimination, meaning discrimination that arises out of a risk assessment based on characteristics commonly held by that group.115 Under this theory, firms do not discriminate because they have a taste for discrimination. Rather, in a world of imperfect information, these firms resort to group characteristics or stereotypes as proxies to evaluate outcome-relevant attributes of individuals. In other words, these firms make the inference that, because an individual belongs to a certain group, she possesses certain traits associated with that group. “In the classic textbook example, if employers believe (correctly) that workers belonging to a minority group perform, on average, worse than dominant group workers do, then the employers’ rational response is to treat [the two groups of workers] differently.”116 Another example is the use of a sex stereotype as a proxy in labor markets. Based on past experience, an employer may believe that, compared to men, women are more likely to leave their jobs during childbearing years. The behavior is rational and (likely) profit-maximizing even when the decisionmaker relies on proxies that are “over-broad generalizations and far from entirely accurate.”117

Redlining—the practice of denying services or raising prices to minority groups—can be the result of such statistical discrimination.118 Just like employers may rely on sex and race as proxies for performance,119 a lender may rely on similar proxies to estimate risk. As a result, what might appear to be systematic taste-based discrimination against a minority group may in fact simply be lenders avoiding loans in high-crime, low-income areas that happen to be heavily populated by the minority group. Economists refer to this form of discrimination as “statistical.” It is also referred to as rational discrimination,120 and some have argued that rational discrimination should be legally permitted.121

There are, of course, other theories of discrimination.122 Our goal here is not to review every possible theory. Rather, following the empirical literature, we focus on the taste-based and statistical discrimination theories.123 This focus allows us to reveal and propose new ways to deal with some of the flaws that plague previous studies. It also allows us to shed new light on and challenge their findings and conclusions. Finally, these two theories have another benefit: they interact differently with the Contact Hypothesis,124 a theory we test. Under this theory, discrimination may be the result of ignorance and, accordingly, can be reduced by contact with members of the minority group. If true, the empirical prediction is that areas with more intergroup contact experience less discrimination. The prediction holds when the discrimination is taste-based. By contrast, contact with minorities may reinforce statistical discrimination if it provides the decisionmaker with new proxies that will allow it to segment the market. For example, a lender who learns that members of a certain minority group suffer from a higher unemployment rate may refuse to sell them loans or require higher interest rates.125 If the lender learns through contact that certain groups are less likely to bargain, the lender may attempt to command higher prices. With these two theories in mind—taste-based and statistical discrimination—we now turn to the world of practice.

2. Two types of studies: the econometric approach and field experiments.

Attempts to empirically address taste-based and statistical discrimination have essentially taken two forms: (a) the econometric approach and (b) field studies. As we explain below, these studies suffer from a number of theoretical and methodological limitations. Understanding the criticism these studies faced and the methodologies they used not only motivates and informs our study but also allows us to extend the literature on discrimination in mortgage lending to discrimination based on sexual orientation.

a) The econometric approach. The first approach is to maintain data at the individual level and assess the likelihood of loan acceptance. This is an attractive approach because lenders typically have guidelines and algorithms that drive the loan acceptance process. In a leading study, researchers were able to obtain all the data associated with whether a loan should have been accepted or denied.126 They were thus able to control for every factor that, according to the banks, was a relevant consideration. The study concluded that an application from a black or Hispanic individual was 8.2 percentage points less likely to be approved than an application filed by a white individual with similar bank-relevant characteristics.127 Follow-up studies questioned the sensitivity of this result and argued that, if anything, it applies only to applications right on the fringe of acceptance.128 Others argued that the single most important factor to a loan application—risk of loan default—is not adequately considered.129

The criticism that received possibly the most attention was that this type of modeling did not address the source of the discrimination, such as whether it was the result of taste-based or statistical discrimination.130 That is, was the observed discrimination evidence of bigotry? Or was race just a proxy for some other neighborhood characteristic associated with the typical black application that lenders might rationally want to avoid? Later studies attempted to answer the motivation question by aggregating the data away from the individual level to the neighborhood level. These studies found much weaker evidence of racial (taste-based) redlining.

As we discuss below,131 we are able to address each of the concerns brought up by the racial redlining literature—specifically that traditional techniques fail to disentangle race effects from neighborhood effects—in a number of ways available to us, thanks to the thoroughness of the HMDA data.132 By doing so, our study is not only the first to use regression-based analysis to study sexual orientation discrimination, but it also invites and sets the ground for future research.

b) Field experiments. With very limited ability to obtain data on the individual level, “[m]uch of the research into housing discrimination, including HUD’s [Housing Discrimination Studies],” had to resort to “paired testing.”133 Under this methodology, “two testers assume the role of applicants with equivalent social and economic characteristics who differ only in terms of the characteristic being tested for discrimination, such as race, disability status, or marital status.”134

While most studies focus on racial discrimination in mortgage lending,135 only a few attempted to investigate sexual orientation discrimination. The first field experiment was conducted in Sweden in 2009 and found evidence of discrimination against same-sex couples.136 The authors sent out two fictitious applications for rental housing via the internet. One application was sent by a couple with a traditionally male and female name. The other application was sent by two distinctively male names, suggesting a gay couple. Each pair also presented itself as a “couple” to explicitly signal their sexual orientation. The authors then measured the rate at which each fictitious couple was called back. They found that, compared to the heterosexual couple, the homosexual couple was 14 percentage points less likely to receive a callback.137 A follow-up study carried out in much the same manner—email correspondence studies—found similar results in the Vancouver, Canada rental market.138

These two studies established some initial evidence of the possibility of discrimination based on sexual orientation, but they have their limitations. Because each study focuses on a specific area and addresses only rentals, we hesitate to draw too much of a conclusion about how these results might translate to mortgage approval rates. This is especially so because antidiscrimination laws differ from one country to another, as do social norms.

A broader concern is whether correspondence studies, which rely on response rates to email inquiries, can serve as a proper measure of discrimination. To begin with, such studies struggle to distinguish between taste-based and statistical discrimination because the underlying motivation for the housing denial is not known to the researcher and because the audit nature of these studies usually prohibits the use of neighborhood fixed effects. The distinction is critical, as different forms of discrimination call for different remedies and measures. Moreover, it is also unclear if the response rate can serve as a proxy for discrimination at all. The Swedish and Canadian studies exemplify the problem with the methodology. In both, a nonresponse was considered a negative outcome and a sign of discrimination.139 By contrast, all responses were considered nondiscriminatory outcomes even though there are many ways bigoted landlords can mask discrimination through a response. Examples are email replies that raise difficulties of actually seeing the apartment140 and responses that redirect the applicant to a different property owner—both of which happened in the Vancouver study.141 It is also likely that some prejudicial landlords provide untruthful responses regarding occupancy. These responses might be strong evidence of actual discrimination, but they were considered a nondiscriminatory outcome.

Another major challenge is whether the results, even if taken as valid, can be generalized. How much can a study in Sweden or Vancouver tell us about housing discrimination generally in the United States? In an effort to answer the question, HUD commissioned a similar email correspondence study.142 Touted as the “first large-scale [ ] study to assess housing discrimination against same-sex couples”143 on a “national scale,”144 the 2011 study conducted 6,833 paired email-correspondence tests across fifty randomly selected markets. The study found that, compared to heterosexual couples, same-sex couples—both male and female—received significantly fewer responses as compared to heterosexual couples.145 There was also some evidence that jurisdictions with state-level prohibitions against sexual orientation discrimination exhibited slightly more adverse treatment against same-sex couples compared with states without such prohibitions.146

The recent HUD study represents a new and improved generation of field experiments. Together with a recent study conducted in the automobile industry, it indicates that sexual orientation discrimination permeates many markets.147 But what the HUD and other studies did not and could not test is how sex and race interact. The automobile study included only white male testers, and in the HUD study, “the only difference between the two e-mails was whether the couple was same sex or heterosexual.”148

3. Sexual orientation in mortgage lending.

To date, only two studies have addressed sexual orientation discrimination in mortgage lending. The first study (Michigan Study) was conducted in 2007 by four of Michigan’s Fair Housing Centers and included 120 pair-tests.149 Each test included two pairs: one posing as a heterosexual couple and the other posing as a same-sex couple with superior credentials (“higher income, larger down payment, and better credit”).150 The study found disparate treatment in 32 (27 percent) of the 120 tests and concluded that discrimination against same-sex couples is widespread.151 The Michigan Study’s conclusion, however, suffers from a number of limitations. To begin with, the study focused on only one state: Michigan.152 The sample size was also small: a total of 120 paired tests.153 Third, the study focused on three markets, of which only 36 (or 30 percent) of the 120 tests were dedicated to discrimination in “home financing.”154 Moreover, home financing exhibited the least amount of discrimination: 20 percent compared to rental (33 percent) and homes sales (25 percent).155 Fourth, the study was conducted in 2007, five years before the enactment of the Equal Access Rule. At that time, discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was allowed with respect to all types of mortgages, including FHA loans. Therefore, the study could not estimate the effectiveness of the Equal Access Rule.

The second study, conducted concurrently with ours, made a number of important findings.156 First, based on a national sample of 20 percent of HMDA data from 1990 to 2015, it found that, “compared to otherwise similar loan applicants,” the gross approval rate for same-sex couples is 3 percent lower.157 Merging the HMDA sample with Fannie Mae Performance Data revealed that same-sex couples whose applications were accepted were charged higher interests expenses at a magnitude of 0.02 to 0.2 percent.158 At the same time, the authors found no evidence that same-sex couples had a higher default risk.159 Professors Lei Gao and Hua Sun’s study makes an important contribution. But it is different from our study in a number of important respects, which do not allow it to answer the questions we investigate here. First, Gao and Sun’s study ignores the legal landscape and assumes that sexual orientation discrimination is not prohibited. Specifically, it ignores the fact that twenty-three states now prohibit sexual orientation discrimination in mortgage lending and that, even within states that do not prohibit the practice, some localities do. As a result, Gao and Sun did not and could not test the impact of state and local rules on acceptance rates. Gao and Sun’s study also does not separately measure discrimination by mortgage type. This could be potentially important, as FHA mortgages are subject to the Equal Access Rule while non-FHA mortgages are not.

Importantly, both studies were designed to test only one variable: sexual orientation discrimination. For this reason, these studies treated all same-sex couples, regardless of their sex (male/female) or race (black/white), as one homogeneous group.160 This design did not allow the authors to test how the interaction between sex and race influences the discriminatory practices identified.161 Nor could the studies identify the effect of local ordinances162 or determine whether and how “differences between the ways lesbians and gay men are treated” impacted the findings.163 Sun and Gao’s failure to distinguish between same-sex male couples and same-sex female couples may also explain the low level of discrimination found in their study—only 3 percent in the HMDA data.164 Our study suggests that same-sex female couples are treated at least as favorably (and in some cases more favorably) as heterosexual couples, which implies that the actual rate of sexual orientation discrimination against same-sex male couples is in fact higher.165

II. The Design, Data, and Findings

A. The Design

Our study is the first attempt to fill the gap and shed light on the very issues that the Michigan Study identified as important but left unanswered. As this Part explains, unlike the field experiments, we study sexual orientation discrimination in all states, using a large number of observations (over five million) and focusing solely on mortgage lending. Importantly, our study is the first to try to investigate how race and sex impact discrimination against same-sex applicants. Our data suggests that race is a critical factor, that lesbians and gay men are treated differently, and that state laws may have a real effect on discrimination against the LGB community.

Our study builds on the prior literature in a variety of ways. As Part II.B explains, based on the critiques of the use of individual-level data, we construct a model that remedies some of the problems identified in prior studies. Our model allows us to look at the individual effects of potential mortgage discrimination. It also takes into account the fact that different minority groups may self-select into neighborhoods and into mortgage applications that have a higher risk of default.

1. Risk considerations.

We take a number of steps to ensure we do not mistake legitimate risk considerations (including proxies that lenders may use to assess the risk of default, such as income or geographic effects) for discrimination. First, and exactly because of the concern that different applicants may carry different levels of risk, we focused only on FHA loans. Applicants for these loans must meet certain predetermined criteria.166 Importantly, for applicants who met the criteria, income and credit scores are less important. In the eyes of the lender, these FHA loans carry the same level of risk because each loan is insured by the federal government.167 This is not to say that FHA loans are risk-free. A high delinquency rate168 can translate into high servicing costs,169 costly regulatory review,170 and sanctions.171 It may also trigger indemnification requirements172 and can result in severe judgments173 and reputational harm.174 However, there is nothing to suggest that lenders believe that same-sex borrowers are more likely to default than other borrowers.175

Second, as we explain in the methodology section, while HMDA data is limited, we do have and control for the applicant’s income. That is, in addition to other controls, we compare loans of applicants with the same level of income.

Finally, we recognize that the neighborhood of the home may actually just be a proxy for bad credit (that is, bad economic neighborhoods generally attract applicants with bad credit). To control for a “neighborhood effect,” we include county-by-bank fixed effects, which controls for any differences across neighborhoods and banks. We are looking at how different compositions of race and gender affect loan acceptance within the same neighborhood by the same bank.176 Moreover, while we do not have the credit score of the applicant, we do know if the loan got denied because of a poor credit score. Thus, while we do not know the intimate details of an applicant’s credit history, we do know and control for those applicants with bad enough credit to disqualify them for an FHA loan. As we explain further below, our empirical design allows us to compare loans of similarly situated applicants (same applicant income, same loan amount, same loan purpose, same risk to the lender, etc.). This design—comparing loan acceptance rates within the same county by the same banks with multiple controls—has an important benefit. It offsets the concern that what we measure is actually just a proxy for some other neighborhood-level characteristic.

2. The proportion of same-sex gay co-applicants in the data.

Our design is still disadvantaged by a key element of sexual orientation discrimination. Other types of discrimination (for example, racial or gender) are typically based on characteristics that are easily observed by both the researcher and the lender. By contrast, sexual orientation is not a salient characteristic that the lender, much less the researcher, can necessarily observe. As a result, we do not and cannot directly observe applicants’ sexual orientation. While initially this may seem like a fatal flaw in our analysis, it is important to remember that the loan officer also does not directly observe sexual orientation. The loan officer can only infer sexual orientation based on observed characteristics (such as the applicant’s style of dress, behavior, etc.) and the perceived relationship between the applicant and co-applicant. While we do not (and cannot) observe sexual orientation, we do observe one important characteristic: whether the applicant is accompanied by a same-sex co-applicant. This is an important characteristic that loan officers observe.

We recognize that this is not a perfect proxy for the applicant’s actual sexual orientation. Indeed, co-applicants can be family members (for example, father and son) or friends, to give a few examples. However, there is strong theoretical and empirical evidence that our estimates do actually measure sexual orientation–based discrimination despite our inability to directly distinguish between same-sex homosexual co-applicants and same-sex heterosexual co-applicants.

a) Theoretical explanations. First, it is important to remember that the applicant’s true sexual orientation is irrelevant. Discrimination is not based on the actual sexual orientation of the applicant but rather on the applicant’s perceived sexual orientation. Discrimination is the result of what the loan officer believes to be true. By using same-sex co-applicants as a proxy for perceived sexual orientation, we are not only following in the footsteps of other researchers;177 we are also following the legal test established in Price Waterhouse. This test focuses on the plaintiff’s “appearance,” “behavior,” and “mannerisms,” as they were perceived by the loan officer.178

Moreover, our findings, if anything, are a conservative measure of the level of discrimination. The fact that we cannot distinguish between (a) same-sex heterosexual co-applicants and (b) same-sex gay co-applicants actually makes our results stronger. In other words, we show that, if the data includes not just gay co-applicants but also heterosexual co-applicants, then the true level of discrimination is actually higher than we report.

The reason is related to the first point: the loan officer cannot observe the co-applicants’ true sexual orientation. In some cases, the loan officer may have information that we cannot observe: for example, whether the same sex co-applicants are a father and son. In other cases, the loan officer may believe that the same sex co-applicants are a gay couple even if they are not. The concern, therefore, is that there are essentially two types of same-sex applications: (a) those applications in which the co-applicants are clearly related, such as a father/son pairing (Group 1), and are therefore not (or less likely to be) perceived179 as gay individuals, and (b) the rest of the same-sex applications, in which the relationship between the applicant and co-applicant is ambiguous to the lender (Group 2). As researchers, we cannot distinguish between Group 1 and Group 2. But if (i) the loan officer has a taste for discrimination and has additional information on the nature of the relationship either through last name or physical appearance (for example, Group 1 looks like a father and son versus Group 2, in which it is unclear), and (ii) the loan officer actually discriminates only against Group 2, then all that does is understate the magnitude of the effect of discrimination. In other words, the inability to distinguish between the two groups, if anything, biases our results toward zero.

To illustrate this point, consider the following example. Suppose the bigoted loan officer does not discriminate against Group 1 members because he has knowledge that is not observable to us as researchers. In such a case, members of Group 1 are 0 percent more/less likely to have the loan approved (that is, they will be treated the same as the white heterosexual benchmark). Now, because the loan officer is bigoted and does like to discriminate against Group 2 members (perceived gay co-applicants), those loans are, say, 12 percent less likely to get accepted. The “true” level of discrimination is 12 percent. However, in our analysis, we necessarily are forced to clump Group 1 and Group 2 loans together. Our resulting estimates average the effect of Group 1 and Group 2, which in this hypothetical would result in an overall effect of loans 6 percent ([0+12]/2) less likely to be approved. Thus, if anything, this ambiguity only understates the level of discrimination (“true” level of 12 percent compared to the estimated effect of 6 percent) but does not invalidate our estimates.

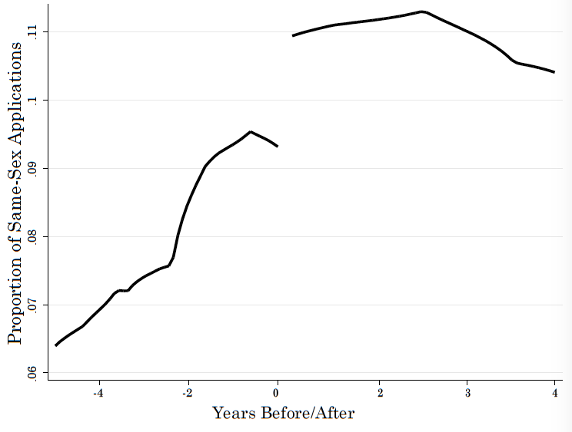

b) Empirical evidence. We further this claim empirically in three ways. First, we track the rate of same-sex loan applications in states and local jurisdictions that passed laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Figure 2 above tracks the proportion of same-sex loan applications over time, centered on the year the law passed (because not all laws are passed in the same year). The horizontal axis measures time in years before and after the law is passed, and the vertical axis measures the proportion of same-sex loans. As Figure 2 demonstrates, there is a marked increase in same-sex loans after the law passes that persists through the end of our data range. Under the assumption that the Group 1 (perceived heterosexual co-applicants, such as parent-child) same-sex loans will not be affected by changes in anti–sexual orientation discrimination laws, Figure 2 suggests that laws are specifically opening the door for more Group 2 (perceived gay co-applicants) loans.

Figure 2 is also consistent with previous research showing that same-sex loan applications increased after the decision in Obergefell v Hodges.180 This study, conducted by HUD in 2016, exploited the “variation across states prior to the Supreme Court decision to investigate the effect of marriage laws on demand for mortgage credit.”181 By using the same methodology that we do—looking at the reported sex of co-applicants—it concluded that states that passed same-sex marriage laws “experienced [an] 8 to 13 percent increase in same-sex mortgage applications.”182

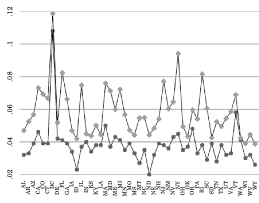

Figure 3: The Relationship between the Size of the LGBT Community and the Proportion of Same-Sex Loans by State183

Second, Figure 3 shows that the number of loan applications with two co-applicants of the same sex correlates to the size of the LGBT community. This suggests that many of the same-sex loan applications in our dataset were submitted by gay or lesbian couples rather than other same-sex co-applicants, such as roommates or relatives of the same sex. In Figure 3, we compare the proportion of same-sex loans per state—the top line—to the actual proportion of individuals in the state that consider themselves part of the LGBT community—the lower line.184 Both lines trend together, with a correlation coefficient of 0.71, suggesting a strong and robust correlation. Essentially, in states with a larger LGBT community, more same-sex applications are filed. Figure 3 therefore suggests that most of the same-sex applications we measure are, in fact, home loan applications filed by gay co-applicants. Part II.C reports the result of a third robustness test leading to the same conclusion.

B. The Model

1. The data and methodology.

Our study relies on three datasets. The first two are proprietary and include state- and local-level protection against antidiscrimination practices in mortgage lending.185 The third has publicly available data on home mortgages reported by financial institutions pursuant to the HMDA. We study every home loan application in the United States reported under the HMDA between the years 2010 and 2015—about five million observations.186 To keep the risk of the loan constant, we restrict the dataset to include only applications made for FHA loans in which the applicant has a co-applicant.187

Our outcome of interest is an indicator variable signifying whether or not the loan was accepted. The variable equals 1 if the loan was accepted and 0 if the loan was rejected.188 In addition to the gender and racial makeup of the applicant and co-applicant, we are able to control for a myriad of factors that influence the probability of whether a home loan is accepted. These include the applicant’s income, loan amount, property type,189 loan purpose,190 whether or not the home will be owner occupied, whether or not the applicant had been preapproved, the applicant’s ethnicity, and the reason for denial, if any. We include each of these variables in each model to account for any observable factor that may influence the bank’s decision to accept or deny the loan.

To account for any national, unobserved trends in the data, we also include in each model year-fixed effects. These dummy variables allow us to control for changes in home loan trends that are common across all loans in a given year.191

Additionally, we control for variation between different banks in the same county and different branches of the same bank in different counties. To see why, suppose that Bank I and Bank II are large national banks with branches in numerous counties in the United States. Bank I may have different lending practices than Bank II. Similarly, a branch of Bank I in one county may have different lending practices than a branch of Bank I in a different county. To control for these two forms of variation (interbank and intrabank), we create a dummy variable for each bank in each county. That is, we create a set of dummy variables for Bank I for each county in each state, and we do the same for all the other banks. These bank-by-county fixed effects absorb all crossbank and crosscounty differences. All the variation that remains is the differences in lending practices within banks in the same county. Put differently, including these fixed effects allows us to look at how the same bank in the same county treats different applications. These variables allow us to exploit the within-bank and within-county variation.192

Discrimination is a comparative term. Accordingly, our comparison group is the white male/white female pair—the most common combination in the dataset. Our independent variables are a set of all the remaining fifteen possible gender and race combinations between a primary applicant and a co-applicant. We thus have a separate dummy variable for each of the following combinations: (1) white male/black male, (2) white male/white male, (3) black male/black male, (4) black male/white male, (5) white female/black male, (6) white female/white male, (7) black female/black male, (8) black female/white male, (9) white female/black female, (10) white female/white female, (11) black female/black female, (12) black female/white female, (13) white male/black female, (14) black male/black female, (15) black male/white female.

Formally, Equation 1 estimates the following linear probability model:

\[L_{ibcy} = a_0 + b_1bmbm_{ibcy} + b_2 bmwm_{ibcy} + b_3wmbm_{ibcy} + b_4 wmwm_{ibcy} + b_5 bcmf_{ibcy} + b_6 bfbf_{ibcy} + b_7 bfwf_{ibcy} + b_8 wmbf_{ibcy} + b_9 wfbf_{ibcy} + b_{10} bmwf_{ibcy} + b_{11} bfmb_{ibcy} + b_{12} bfwm_{ibcy} + b_{13} wfwf_{ibcy} + b_{14} wfwm_{ibcy} + b_{15} wfbm_{ibcy} + X_{ibcy} + \tau_y + \rho_{bc} + e_{ibcy}\]

Where $L_{ibcy}$ represents whether or not loan application i was accepted at bank b in county c in year y. $X_{ibcy}$ is a matrix of covariates that influence the probability a home loan is accepted,193 $\tau_y$ is a set of time-fixed effects, $\rho_{bc}$ is the set of bank-by-county fixed effects, and $e_{ibcy}$ is the error term. The remaining fifteen variables measure the effect of each unique pair of race and gender combinations. Accordingly, the coefficient $b_k$ can be interpreted as the percentage point change in the probability of loan acceptance. The omitted group is a white male applicant with a white female co-applicant.

2. Model validity.

HMDA data is rich and provides the most complete coverage of the loan application process.194 Still, there are many concerns that need to be addressed.

a) Linear probability modeling. A restricted dependent variable, such as a binary outcome of whether or not a loan was accepted, violates the assumptions of ordinary least squares estimation (OLS), in part because the dependent variable is not continuous but also because the standard errors are misestimated. Additionally, it is possible for a linear probability model (OLS applied to a binary outcome variable) to produce model estimates that yield a nonsensical predicted probability that is greater than one. Alternative estimation techniques such as logit and probit models correct for this by constraining the model to be bound between zero and one. These models, however, come with their own set of assumptions and perform equally as poorly, if not worse, than linear probability models.195

In the context of this Article, we are able to alleviate the typical concerns associated with linear probability modeling. First, we adjust for bias in the estimation of the standard errors by clustering the standard errors in each model at the state level. Second, in our dataset, 47 percent of the loans we analyze were accepted. Thus, the oft-voiced critique that linear probability models perform poorly when there are very few events (that is, no loans were accepted) or very few nonevents (in other words, almost all loans are accepted) is not an issue.196 Lastly, we are mostly interested in calculating marginal effects for each of the pair combinations and less concerned about making predictions or forecasts of the full model. Accordingly, the concern that a linear probability model could produce predictions of a probability greater (or less) than one is not an issue. We turn to review other potential pitfalls discussed in the home mortgage literature, which are not specific to Equation 1.

b) Demographics as an endogenous instrument for economic conditions. Many early studies of home mortgage discrimination pointed to the possibility of race, or any other demographic, as nothing more than a proxy for another, unobserved variable.197 For instance, if blacks disproportionally apply for home loans in more economically disadvantaged neighborhoods, lenders may be more likely to deny the loan application. The reason is not due to racial discrimination but rather due to the perceived high risk of extending a loan to applicants residing in such neighborhoods. As we previously mention, economists often refer to this type of discrimination as statistical discrimination: discrimination that is based on a factor other than a demographic characteristic.

Our study finds more conclusive evidence that the motivation for discrimination is taste-based, or bigotry, than any previous econometric study. The reason is that, unlike with race, lenders are less likely to rely on perceived sexual orientation as a proxy for increased risk.198 Moreover, given the sheer magnitude of the dataset HMDA offers, we are able to control for lender-by-county fixed effects. That is, our analysis compares loan applications considered by the same lender from those who reside in the same county, which by definition has the same risk to the lender (they are all FHA loans).199 It is thus very likely that the reason for any disparate treatment was not based on factors relevant to risk assessment but on the applicants’ perceived sexual orientation.200

c) Risks observed by the bank but not by the researcher. There is also some concern that there are factors that the lenders are able to observe and include in a risk assessment of the loan application that we, as researchers, are not able to observe in the data. The most glaring example is credit scores, which are probably the single strongest indicator of risk and are a factor observed by the lender.201 Despite its richness, HMDA does not include credit scores. However, as Part II.A.1 explains above, our research design allows us to address and mitigate this concern in a myriad of ways, one of which is by focusing solely on FHA loans.202 The unique feature of these loans is that they carry the same low level of risk to the lender. An applicant approved for an FHA loan pays an FHA insurance premium. In case of a default, the lender recoups the losses from the government.203 As a result, every FHA loan bears the same risk and expected return to the lender regardless of the demographic characteristics of the applicant. Accordingly, it is unlikely that disparate treatment in FHA loan denial can be traced to an unobserved (to the researcher) measure of risk.

C. Results

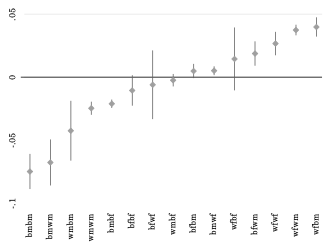

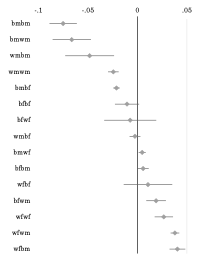

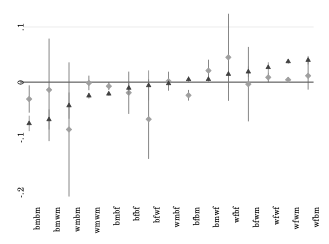

The results for our main analysis of Equation 1 can be seen in Table 2 and graphically in Figure 4.

| Applicant | Co-applicant | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Male | Black Male | -0.038** (0.017) |

-0.043*** (0.014) |

| White Male | White Male | -0.021*** (0.005) |

-0.025*** (0.003) |

| Black Male | Black Male | -0.087*** (0.008) |

-0.075*** (0.009) |

| Black Male | White Male | -0.070*** (0.014) |

-0.068*** (0.011) |

| White Female | Black Male | 0.012*** (0.004) |

0.040*** (0.005) |

| White Female | White Male | 0.012*** (0.001) |

0.037*** (0.003) |

| Black Female | Black Male | -0.038*** (0.004) |

0.005 (0.003) |

| Black Female | White Male | -0.007 (0.008) |

0.019*** (0.006) |

| White Female | Black Female | -0.028 (0.017) |

0.014 (0.015) |

| White Female | White Female | -0.012*** (0.002) |

0.027*** (0.006) |

| Black Female | Black Female | -0.062*** (0.006) |

-0.011 (0.007) |

| Black Female | White Female | -0.043*** (0.015) |

-0.006 (0.017) |

| White Male | Black Female | 0.006* (0.003) |

-0.002 (0.003) |

| Black Male | Black Female | -0.033*** (0.003) |

-0.021*** (0.002) |

| Black Male | White Female | 0.011*** (0.002) |

0.005** (0.002) |

| Controls Sample Size R Squared |

5,864,086 0.32 |

X 5,864,086 0.42 |

In Table 2, Column (1) estimates Equation 1 with the inclusion of year and bank-by-county fixed effects, but with no other controls. Column (2) reports the results with the controls mentioned previously.205 In both models, the corrected standard errors clustered at the state level are in parentheses. Each coefficient can be interpreted as the percentage point increase (if positive) or decrease (if negative) in the likelihood of a loan to be accepted for each applicant/co-applicant pair relative to a white male/white female applicant pair. For instance, from Column (2) in Table 2, a pair consisting of a white male applicant and a black male co-applicant is 4.3 percentage points less likely to have a loan accepted as a white male/white female pair asking for the same loan amount with the same income from the same lender in the same county. This means that, if a white male/black male pair has a 45 percent chance of having a loan application accepted, we would expect a white male/white female pair to have a 49.3 percent chance of approval. This is so despite the fact that both pairs requested the same amount for the same purpose with the same income from the same lender in the same county and bear the same level of risk to the lender.

Figure 4: Effect of Gender and Racial Composition on Co-applicant Loan Acceptance206

Figure 4 organizes the results in Table 2 from most negative to most positive and includes bands that represent 90 percent confidence intervals. To interpret Figure 4, focus first on the points at the center of the intervals. A point that lies below the zero line suggests the race/gender pairing is less likely to have a loan accepted, and a point above the line suggests the acceptance is more likely. Now focus on the intervals. If an interval intersects with the zero line on the horizontal axis, the estimated effect is not statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

To test once again whether the results are driven by same-sex gay co-applicants (rather than by same-sex heterosexual parent-child co-applicants),207 we remove from the dataset any applicant or co-applicant that reports more than one race. The rationale is that keeping only “single-race” applicants would (likely) exclude from the data parent-and-child co-applicants. The reason is that it is unlikely that a co-applicant who reports one race (for example, black) will be the parent of the applicant with only one different race (for example, white). We report the results of this regression graphically in Figure 5 below. Figure 5 shows that, when the sample is restricted to the types of same-sex loans that are more likely representative of actual gay couples (Group 2208 ), the results hold and in some cases are slightly stronger.

The empirical evidence suggests that a large portion of the same-sex loan applications are actually loans submitted by gay couples. Moreover, the differences between the results that Figures 4 and 5 report are also consistent with our theoretical prediction in Part II.A that our results are a conservative measure of discrimination and that the actual level of discrimination is higher than we observe.

1. National patterns in discrimination.

With this in mind, we turn to analyze the results. Figure 4 provides strong evidence of systemic and widespread discrimination against gay male couples. More specifically, Figure 4 shows that any application with a pair of males is statistically less likely to be approved relative to the same white heterosexual pair. Within the same-sex male pair groups, race plays a role. Although all same-sex male applications are less likely to be accepted, black-male pairs are the least likely to be approved (-7.5 percentage points), followed by the interracial pairs of black male/white male (-6.8), white male/black male (-4.3) and white male pair (-2.5). Interestingly, the exact same pattern holds for female pairs. From the least to most likely to be approved are black female pairs, followed by interracial black female/white female and white female/black female pairs, and white female pairs. In the case of same-sex pairs (that is, male/male and female/female pairs), the data reveals some evidence of a statistically significant “primary applicant” effect. The differences between interracial pairs, however, are statistically indistinguishable from one another.