Empirical Patterns of Pro Se Litigation in Federal District Courts

Pro se litigants face a number of challenges when bringing civil litigation. One potential solution to these challenges, endorsed by members of the judiciary and the legal academy, is pro se reform at the trial court level: offering special services to pro se litigants in order to help them successfully navigate the legal system. This Comment offers the first publicly available empirical assessment of several pro se reform efforts thus far. The analysis shows that these pro se reforms have not succeeded in improving pro se litigants’ win rates at trial. This Comment thus suggests that, while pro se reforms likely have important merits, such as enabling a more thorough and dignified hearing process for pro se litigants, on average these reforms do not alter the final outcomes of the litigation process.

Introduction

In September 2017, Judge Richard Posner abruptly resigned from the Seventh Circuit. In subsequent interviews, Posner explained that he resigned in part because of his disagreement with his judicial colleagues over the Seventh Circuit’s treatment of pro se litigants (those litigants who appear before courts without lawyers).1 In particular, Posner thought the court wasn’t “treating the pro se appellants fairly,” didn’t “like the pro se’s,” and generally didn’t “want to do anything with them.”2

Posner’s resignation is a powerful reminder of the challenges pro se litigants continue to face. His belief that pro se litigants are frequently mistreated in civil litigation and denied a full and fair opportunity to vindicate their claims is neither new nor limited to federal appellate courts.3 Numerous legal commentators have expressed similar concerns.4 Yet, though the belief that pro se litigants are underserved by the legal community is widespread, the full extent of the challenges they face in court is still only partially understood.

At the same time, there has been considerable consternation over the growing volume of judicial and legal resources consumed by pro se litigants.5 Many pro se litigants bring dubious claims.6 Time and energy expended on these claims is time and energy that cannot be expended on other legal issues.

Any reform must simultaneously balance a number of key policy goals: it should ensure the ability of pro se litigants to receive fair trials without unfairly disadvantaging their adversaries, allocate sufficient resources to ensure quick and fair hearings while avoiding overdrawing on judicial and legal resources that might instead be put to more urgent needs,7 and be practicable within the Supreme Court’s current jurisprudence and the statutory authority granted to courts by Congress.

A number of commentators have trumpeted reforms at the trial court level geared toward assisting pro se litigants as a possible solution.8 These reforms usually aim to give pro se litigants access to resources and information that can help them successfully navigate the legal process, reduce their costs, or provide them with assistance from courts’ offices.9 Examples of reforms that have been implemented include providing pro se litigants with access to electronic filing systems that make it easier to file lawsuits and monitor proceedings, allowing pro se litigants to communicate with law clerks about their claims and proceedings, and publicly disseminating information about resources that may be available to pro se litigants through the court or third parties.10 Critically, these reforms can be implemented by the trial courts and their staff and do not require significant additional contributions from attorneys, clinics, or other legal institutions. Accordingly, these programs can help pro se litigants without diverting legal resources away from other causes, including indigent criminal defense. A large number of federal district courts have already implemented at least some of these procedural reforms aimed at helping pro se litigants.11

This Comment furthers the legal community’s understanding of issues in pro se litigation by conducting an empirical analysis of pro se reforms in federal district courts. By comparing case outcomes for pro se litigants in district courts that have implemented these types of reforms with the outcomes of similarly situated pro se litigants in courts that have not implemented any reforms, this Comment provides an initial assessment of the impact of those reforms. The analysis reveals that thus far, a wide range of reforms undertaken by federal district courts have not significantly impacted case outcomes for pro se litigants. This analysis conflicts with the intuitions of the Supreme Court, commentators, and judges and clerks of district court offices, who have indicated their belief that these reforms are effective.

Importantly, this Comment does not suggest that these reforms have been failures. These reforms may have improved the pro se litigation process by making it feel more humane and easier to understand and by giving litigants a stronger sense that their concerns have been heard. Moreover, these reforms may still ease the burden of pro se litigation on courts by helping courts understand the issues involved more clearly or by moving cases through the judicial system more quickly. The analysis does suggest, however, that district court reforms have been ineffective in improving case outcomes for pro se litigants, and alternative approaches should be considered.

Accordingly, this Comment suggests that pro se trial court reform is not the silver bullet that some commentators have hoped for in the quest to remedy the shortcomings of the pro se litigation process. In order to meaningfully improve case outcomes for pro se litigants, the legal community will either need to implement different and potentially more dramatic reforms than those implemented thus far or consider another approach altogether, such as renewed advocacy for “civil Gideon.”12 Alternatively, it is also possible that there is no cost-effective way to improve case outcomes for civil pro se litigants in the context of the modern US legal system. This Comment does not analyze the merits of these options. Instead, it strongly suggests that a different solution is needed to ensure pro se litigants get a full and equal opportunity to have their claims redressed via litigation.

This Comment proceeds as follows. Part I provides an introduction to relevant case law, as well as key perspectives in the academy, on the rights of pro se litigants and procedural safeguards to protect pro se litigants. Part II presents an empirical overview of pro se litigation in federal district courts and contextualizes the typical types and outcomes of pro se litigation within the context of the federal docket. Part III details some of the policies that federal district courts have implemented thus far to improve the results of pro se litigation by comparing pro se outcomes in courts that have implemented those reforms with pro se outcomes in courts that have not implemented those reforms, and it demonstrates that those measures have not impacted case outcomes. Part IV then describes and analyzes the effects of wholesale reforms to the pro se litigation process in the Eastern District of New York (EDNY) by comparing case outcomes for pro se litigants in EDNY with those of neighboring districts before and after the implementation of reforms. Part IV bolsters the findings of Part III by showing that EDNY’s wholesale pro se reform also did not impact the win rates of pro se litigants. Part V discusses some of the implications of the results detailed in Parts III and IV, and the Conclusion summarizes the contribution of this Comment and identifies some opportunities for future research.

I. The Rights of Civil Pro Se Litigants

There is limited Supreme Court jurisprudence on trial-court reforms for civil pro se litigants. However, an extensive body of case law establishes the right to counsel for indigent criminal litigants and then denies that right to civil litigants who cannot afford counsel. Moreover, in one recent case, Turner v Rogers,13 the Supreme Court established a limited right to procedural protections for civil pro se litigants, creating the potential for new jurisprudence establishing new rights for civil pro se litigants.14

A. Case Law on the Rights of Pro Se Litigants at Trial

Over the past hundred years, unrepresented litigants have brought numerous lawsuits to determine the extent to which the Constitution guarantees the right to counsel, mostly focusing on the textual guarantees in the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments.15 The Sixth Amendment famously states that, “[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to . . . the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.”16 The Supreme Court has clarified the scope of the right to counsel in criminal prosecutions through a series of landmark cases, gradually converting a guaranteed right to provide one’s own counsel into a right to government-provided counsel whenever a criminal defendant is unable to procure counsel.17 However, the Supreme Court has taken a much narrower view of the right to counsel, and legal protections more generally, for pro se litigants in civil cases.18

From the 1930s through the 1970s, the Supreme Court gradually strengthened the right to counsel in criminal prosecutions in a series of landmark decisions. Ultimately, this led to the Supreme Court’s current position: defendants have the right to counsel in essentially all criminal prosecutions.19 The first key case in this series was Powell v Alabama.20 In Powell, the Supreme Court held for the first time that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires states to respect the right to counsel in at least some criminal trials.21 Under Powell, the right to adequate counsel was guaranteed only for capital cases. The Court explicitly declined to reach the question of whether states needed to provide a similar guarantee of access to counsel in noncapital cases.22

Over the next thirty years, the Supreme Court slowly expanded the right to counsel for criminal defendants. Shortly after Powell, in Johnson v Zerbst,23 the Supreme Court held that the Sixth Amendment protects the right to counsel for all criminal defendants in federal courts.24 Additionally, the Court held that, when the accused “is not represented by counsel and has not competently and intelligently waived his constitutional right” to counsel, any criminal conviction will be ruled unconstitutional as a Sixth Amendment violation.25 The Supreme Court initially declined to extend Zerbst to all criminal cases in state courts, instead reaffirming, as it held in Powell, that the right to counsel was guaranteed only in capital cases in state courts. In Betts v Brady,26 the Court declined to overturn a robbery conviction even though the trial court had refused the defendant’s request for the assistance of counsel, holding that states were not constitutionally mandated to provide adequate counsel for state trials in noncapital cases.27

In 1963, the Supreme Court broke from precedent and found the right to counsel to be a “fundamental safeguard[ ] of liberty” guaranteed to all criminal defendants by the Constitution.28 In the landmark case Gideon v Wainwright,29 Clarence Earl Gideon was charged in Florida state court with breaking and entering with intent to commit petty larceny.30 Gideon appeared alone in court and requested a court-appointed attorney to assist his case. The Florida court declined, as Florida did not provide counsel for criminal defendants in noncapital cases.31 After granting certiorari,32 the Supreme Court held that the Due Process Clause requires states to provide counsel in noncapital criminal cases, overturning Betts. The Court focused on the “fundamental” nature of the right, comparing it favorably to rights like freedom of speech and freedom from cruel and unusual punishment, and the Court held that the Due Process Clause prohibited states from violating the right.33 This holding, along with its extension to misdemeanors in Argersinger v Hamlin,34 established the modern right to counsel in all criminal cases.35

Following Gideon, legal activists began a push to extend the right to counsel into the civil sphere. Advocates argued that the right to counsel should be extended to civil cases in which the litigants’ essential rights were at stake.36 Those activists have had limited success; the Supreme Court has declined to find a right to counsel in civil litigation. In one notable case, Lassiter v Department of Social Services,37 the appellant argued that failing to provide counsel in a civil suit that would terminate parental rights violated the Due Process Clause.38 A 5–4 majority on the Supreme Court held that there was no general right to appointment of counsel in parental termination proceedings despite the importance of the right involved. The Court explained that a litigant’s interest in personal liberty, not the general interests of litigants in vindicating legal rights, was the critical question in determining whether the litigant has a right to counsel.39 Accordingly, in a blow to civil Gideon activists, the Supreme Court held that there was a “presumption that there is no right to appointed counsel in the absence of at least a potential deprivation of physical liberty,” signaling the Supreme Court’s reluctance to extend the right to counsel to civil litigants.40 Lassiter remains good law.

Turner, the most recent Supreme Court ruling on the rights of civil pro se litigants, threw an unexpected twist into this line of cases and provided fodder for both proponents and detractors of the expanded right to counsel for civil litigants. In Turner, all nine justices agreed that the state was not required to provide counsel in a civil contempt hearing even if the contempt order would have resulted in incarceration.41 Nonetheless, a five-justice majority overturned the sentence, holding that the state must “have in place alternative procedures that ensure a fundamentally fair determination of the critical incarceration-related question.”42 The Court highlighted a “set of ‘substitute procedural safeguards’”—for example, notice about critical issues in the case, the use of forms to elicit relevant information, and other potential protections—that could stand in for assistance of counsel and ensure the “‘fundamental fairness’ of the proceeding even where the State does not pay for counsel for an indigent defendant.”43

Commentators have seen Turner as a complete rejection of civil Gideon, effectively foreclosing the possibility of an expanded right to counsel in civil litigation, at least for the foreseeable future.44 However, commentators have also seen the holding in Turner—that due process requires trial courts to protect pro se litigants’ rights via procedural safeguards—as a nod toward a new and potentially more fruitful approach to pro se litigation: reforms in trial courts.45

B. Commentary and Debate: Civil Gideon

The movement for civil Gideon began shortly after the holding in Gideon established the modern understanding of the right to counsel in criminal cases.46 Although there is some disagreement among its supporters about the proper breadth of civil Gideon, the movement has generally focused on providing counsel for indigent parties in proceedings involving threats to their basic needs.47 From the movement’s inception, commentators have been divided over the merits of civil Gideon. Advocates have put forth a number of arguments in favor of civil Gideon. They have argued that representation in civil litigation secures constitutional rights to due process and equal protection of law, is necessary to ensure fair trials, is “sound social policy,” and helps ensure more consistent outcomes for defendants.48 Critics have countered with both direct refutations and alternative suggestions. They have argued that Gideon wasn’t that effective in aiding criminal defendants, so civil Gideon would not be either; civil Gideon would be ineffective notwithstanding the effectiveness of Gideon; civil Gideon would undermine criminal defense by reallocating legal resources to civil litigation; and, regardless of whether it would be a good idea, it simply isn’t realistic to expect any judicially created civil Gideon given the current composition of the Supreme Court.49

Proponents and detractors within the civil Gideon debate disagree on how effective civil Gideon would be in improving case outcomes for pro se litigants. One reason for this is that commentators disagree about how effective Gideon itself has been at improving case outcomes for criminal defendants.50 Many of the reasons commonly given for the failure of Gideon, such as the political difficulty of allocating sufficient resources to defense lawyers and the high bar for claiming ineffective assistance of counsel, would likely apply with equal or greater force in the context of civil Gideon.51

Beyond the difficulties specific to civil Gideon, there is also empirical uncertainty regarding the value of access to counsel. Dozens of experimental studies have attempted to shed light on the effectiveness of attorneys in various settings in aiding litigants who would otherwise be proceeding pro se.52 One 2010 meta-study conducted on a selection of prior studies suggested that representation by counsel improved a party’s odds of winning a suit by a factor between 1.19 and 13.79.53 While those numbers suggest that access to counsel probably increases a litigant’s odds of winning a case by at least some margin, the size of the range limits the value of these studies to policymakers.54 There is also debate concerning the quality of most of these studies. A 2012 article by Professor D. James Greiner and Cassandra Wolos Pattanayak looked at dozens of previous studies to quantify the added value of access to counsel and found almost all of those studies were unable to accurately measure the effect of access to counsel.55

However, the few reliable studies conducted thus far tend to suggest that providing access to counsel significantly improves outcomes for civil litigants. Greiner and Pattanayak identified two prior studies that were properly conducted to evaluate the effects of access to counsel. While noting it was premature to draw conclusions, they pointed out that one of those studies found that access to counsel was effective in improving case outcomes, and the other study found it effective in improving case outcomes in one of its two experimental settings.56 A follow-up experiment by Greiner, Pattanayak, and Jonathan Hennessy found that the assistance of counsel led to a significant improvement in litigation outcomes compared to more piecemeal assistance.57 Specifically, they found that, from a sample of litigants facing eviction in a district court, about one-third retained their rental units after receiving unbundled legal assistance—legal aid short of an attorney-client relationship—whereas approximately two-thirds retained their units after receiving both unbundled legal assistance and representation by counsel.58 Overall, though the body of evidence is still limited, the empirical evidence suggests that providing lawyers for pro se litigants substantially improves case outcomes for those litigants. Critically, this implies that providing adequate access to counsel may substantially improve case outcomes for a meaningful percentage of pro se litigants.59

C. A Happy Medium? Pro Se Reform in Trial Courts

As the plausibility of civil Gideon has diminished in the wake of Turner, trial court reforms for pro se litigants have emerged as a compromise. Both proponents and critics of civil Gideon see major potential benefits of pro se reform: it is a low-cost option that could conceivably provide meaningful benefits to pro se litigants without diverting legal resources from more critical cases, it helps ensure pro se litigants will receive fundamentally fair hearings, and it is a more politically and jurisprudentially feasible solution than civil Gideon.60

Some still remain skeptical about pro se reform. Commentators have argued that unfair advantages for pro se litigants correspond to unfair disadvantages for their opponents in civil proceedings, that tweaking the court system specifically for pro se litigants undermines the rule of law, and that reforms may lead courts to devote more resources to cases that often prove frivolous.61 Other detractors of trial-court reform for pro se litigants have opposed it on opposite grounds, arguing that these reforms may be counterproductive and harm pro se litigants62 or that they don’t go far enough and that civil Gideon is needed to fully protect the rights of pro se litigants.63

Unlike civil Gideon advocates, reform advocates have been successful in implementing pro se reform. A 2011 survey by the Federal Judicial Center of United States District Courts (“FJC Survey”) found that eighty-seven of ninety responding districts had implemented at least one program or procedure to assist pro se litigants.64 Similar reforms have been undertaken in at least some state and local courts as well.65

Courts have implemented a number of different programs and procedures to assist pro se litigants. For example, the 2011 FJC Survey revealed that twenty-five districts allowed pro se law clerks to directly communicate with pro se litigants about their cases; thirty-five districts allowed pro se litigants to electronically access information about the docket sheet, pleadings, and more through case management/electronic case filing (CM/ECF); nineteen disseminated information about programs for pro se litigants outside the court, such as in public libraries; and ten provided software specifically designed to help pro se litigants prepare their proceedings.66 These types of reforms mirror those suggested by the Supreme Court in Turner:67 for example, providing notice to pro se civil litigants of important issues affecting the case and using forms to solicit relevant information. Likewise, giving access to the docket sheet and pleadings through CM/ECF and allowing communication with a pro se law clerk somewhat fulfills the Supreme Court’s suggestion to increase efforts to provide pro se litigants with notice. The pro se software typically helps simplify filing and participation in civil proceedings, similar to forms that would solicit relevant information.

Courts and commentators appear to believe these reforms are effective. Chief judges and clerks of courts were asked in the FJC Survey about the most effective measures for helping nonprisoner pro se litigants. Tables 1.1 and 1.2, reproduced from the FJC Survey below, show that both clerks’ offices and chief judges at district courts believe measures like those discussed above are effective at improving outcomes for nonprisoner pro se litigants.68

|

Measures |

Number of Mentionsa |

|---|---|

|

Information and guidance tailored to the pro se litigant (for example, standardized forms, |

48 |

|

Pro bono program, mediation/settlement |

13 |

|

E-filing, CM/ECF access |

12 |

|

Special staff arrangements or assignments, staff training, internal reports |

12 |

|

Other |

4 |

a. There were 66 respondents; they mentioned 89 measures.

|

Measures |

Number of Mentionsa |

|---|---|

|

Handbooks; standardized forms; instructions; other materials |

33 |

|

Personal assistance by clerk’s office staff and/or pro se law clerks |

9 |

|

Specially designated staff; procedures for |

5 |

|

Other |

2 |

a. There were 33 respondents; they mentioned 49 measures.

Tables 1.1 and 1.2 demonstrate that a large proportion of clerks’ offices and chief judges at district courts believe that pro se reform measures are helpful to nonprisoner pro se litigants.71 For example, the majority of clerks’ offices surveyed in the FJC Survey believe that making information and guidance tailored to pro se litigants readily available is one of the most effective measures for helping nonprisoner pro se litigants. The vast majority of responding chief judges believe handbooks and standardized materials are helpful, and about 25 percent of chief judges surveyed believe that personal assistance by the clerk’s office staff is helpful to pro se litigants. Often, these handbooks and standardized materials are extensive. For example, the Northern District of Illinois’s website currently has a thirty-five-page generalized handbook advising pro se litigants72 and specific instructions and forms for how to handle civil rights, employment discrimination, and mortgage foreclosure cases.73

Despite courts’ and commentators’ optimism about these reforms, there has been no publicly available empirical analysis of the effects of these reforms on case outcomes in pro se litigation thus far. There is some literature discussing the impacts of pro se court reforms in a more general sense,74 but that literature does not focus on the effect on case outcomes. This Comment seeks to fill that gap by providing an initial analysis of how reforms implemented by courts thus far have impacted case outcomes for pro se litigants.75

II. Empirical Summary of Pro Se Litigation

A. Sample

The primary dataset used in this Comment consists of administrative records of civil cases filed in federal district courts, which are collected and published by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts (AO).76 The AO dataset includes the district court in which the case was filed, the docket number of each case, the date on which the case was filed, the nature of the suit, the procedural progress of the case at the time the case was disposed of, the manner in which the case was disposed of, the party that the final judgment of the case was in favor of, and whether the plaintiff or the defendant was a pro se party.77

| ’98–’01 | ’02–’05 | ’06–’09 | ’10–’13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases Per Year, thousands | ||||

| Both Parties Represented | 145 | 167 | 175 | 185 |

| Pro Se Plaintiffs | 15 | 17 | 18 | 21 |

| Pro Se Defendants | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| % Pro Se Plaintiffs | 9.1% | 9.0% | 9.0% | 9.8% |

| % Pro Se Defendants | 1.9% | 2.2% | 1.9% | 2.5% |

As seen in Table 2A, civil nonprisoner pro se litigation appears to comprise a stable proportion of federal district courts’ dockets.78 Averaged over several four-year time periods, the percentage of cases in federal district courts that were filed by pro se plaintiffs has ranged only from 9 to 10 percent. However, that still constitutes an average of more than fifteen thousand federal district court cases each year involving nonprisoner pro se plaintiffs. Similarly, the percentage of cases that have been answered by pro se defendants has hovered around 2 percent.

Commentators writing about pro se litigation over the past twenty years have typically described pro se litigation as a large and growing portion of the federal docket.79 However, when the scope of the inquiry is limited to nonprisoner pro se litigation, this trend does not show up in the AO data. There has been a meaningful upward trend in the total number of pro se cases. But the percent of cases brought by pro se plaintiffs has not changed significantly, as seen in Table 2A, suggesting pro se litigation comprises a relatively stable portion of the federal docket.

The exclusion of prisoner pro se litigation is a potentially consequential choice. Commentators sometimes discuss trends in prisoner and nonprisoner civil pro se litigation without differentiating between the two classes, but there is no reason to assume that trends in prisoner pro se litigation mirror trends in nonprisoner pro se litigation.80 Prisoner pro se litigation may be an interesting topic of its own. However, most prisoner litigation consists of several unique case types that are pseudocriminal in nature, particularly habeas petitions, that are not necessarily similar to other types of civil pro se litigation. Accordingly, the scope of this Comment excludes cases that are predominantly brought by prisoners in order to focus more narrowly on the dynamics of civil nonprisoner pro se litigation in federal district courts.81

B. Case Outcomes for Pro Se Litigants in Federal District Courts

One of the most important aspects of pro se litigation in federal district courts is that pro se litigants fare extremely poorly. This is generally understood in the literature.82 However, the magnitude of the disparity between pro se and represented litigants is not always highlighted. Accordingly, this Section presents statistics on typical outcomes for represented and pro se litigants in trial. Tables 2.2 and 2.3 show the win rates of plaintiffs and defendants in cases that reach a final judgment based on whether both parties are represented, the plaintiff is proceeding pro se, or the defendant is proceeding pro se.

|

Judgment For |

Plaintiff |

Defendant |

Both |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Plaintiff |

3% |

73% |

42% |

|

Defendant |

82% |

12% |

42% |

|

Both |

1% |

3% |

4% |

|

Missing/ |

14% |

12% |

10% |

|

Judgment For |

Plaintiff |

Defendant |

Both |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Plaintiff |

4% |

86% |

51% |

|

Defendant |

96% |

14% |

49% |

As Tables 2.2 and 2.3 demonstrate, the presence of a pro se plaintiff or pro se defendant dramatically changes the dynamics of litigation. When both parties are represented and there is a recorded final judgment for either the plaintiff or the defendant, the plaintiff and the defendant each win roughly 50 percent of the time. When the plaintiff proceeds pro se, the plaintiff instead wins about 4 percent of the time. When the defendant proceeds pro se, the plaintiff wins 86 percent of the time. These differences are stark. A represented defendant will nearly always prevail over a pro se plaintiff in court. A represented plaintiff will win almost as consistently against a pro se defendant.

Though dramatic, these numbers do not necessarily imply that lack of access to counsel worsens case outcomes for pro se litigants. There are a number of plausible explanations for low win rates by pro se litigants even if pro se litigants are not disadvantaged in court. For instance, and likely most significantly, because lawyers frequently work on a contingency fee basis, a lawyer is more likely to agree to work on behalf of a plaintiff with a strong case than a plaintiff with a weak case.84 The stronger the plaintiff’s case, the higher the expected damages and expected payout for the lawyer. Hence, it is less likely that strong cases proceed pro se.

While the outcome gap between pro se and represented litigants does not necessarily prove that lack of access to counsel causes poor case outcomes for pro se litigants, it is easy to see how it motivates proponents of pro se court reforms or civil Gideon. Table 2C suggests that, whenever one of the parties is proceeding pro se, the likelihood that any final judgment will be registered for the other party is overwhelming. If one believes that a meaningful portion of pro se litigants have important rights that they are seeking to vindicate in court, it is likely they are not receiving adequate remedies under the current legal system.85

C. Types of Suits Brought by Pro Se Litigants

Another important aspect of pro se litigation to examine is the types of suits regularly brought by pro se litigants. This Section provides several tables that highlight the frequency of pro se litigants across different types of legal claims and show which specific case types most frequently feature pro se litigants. Despite the fact that roughly 10 percent of federal district court litigation involves a pro se plaintiff, some types of litigation very rarely involve pro se plaintiffs, while other types of cases are brought by pro se plaintiffs much more than 10 percent of the time. The story is similar for pro se defendants, though the variation is less dramatic because pro se defendants comprise only 2 percent of defendants in civil suits in federal district courts. Even in light of this variance, pro se litigants comprise a significant raw number of civil suits in all categories.

| Suit Category | Total Cases | % Pro Se | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thousands | Plaintiff | Defendant | |

| Products Liability | 19.2 | 2% | 0% |

| Civil Rights | 17.9 | 32% | 2% |

| Tort | 16.7 | 7% | 1% |

| Labor | 15.5 | 3% | 2% |

| Government | 15.1 | 8% | 2% |

| Contract | 15.0 | 4% | 3% |

| Employment Discrimination | 14.5 | 19% | 0% |

| Statute | 11.2 | 11% | 4% |

| Asbestos | 11.1 | 1% | 0% |

| Insurance | 8.4 | 2% | 2% |

| Property | 6.2 | 13% | 12% |

| Financial | 6.1 | 13% | 4% |

| Administrative | 5.7 | 8% | 3% |

| Other | 14.3 | 7% | 4% |

| All | 176.8 | 9% | 2% |

Table 2D shows the most common types of litigation in federal district courts and the frequency with which each type of case involves a pro se plaintiff or defendant. Pro se plaintiffs bring a disproportionately large percent of civil rights and employment discrimination cases. In contrast, pro se plaintiffs rarely bring other types of cases, such as products liability, contract, asbestos, and insurance cases.86 Table 2D also shows that the only types of cases that frequently involve pro se defendants are property cases, which are primarily foreclosure proceedings.87 Perhaps the most important takeaway from Table 2D is that a substantial proportion of many types of cases are brought by pro se plaintiffs. Though there is significant variance—pro se litigants bring 32 percent of civil rights cases but bring a more modest 8 percent of cases involving the government and 2 percent of insurance and product liability cases—pro se litigants are prevalent across many types of cases. Any reforms targeting just one type of lawsuit cannot fully address the scope of issues faced by pro se litigants.

Tables 2E and 2F, the final tables in this Part, examine how win rates for pro se litigants vary across different types of cases. The win ratios in Table 2E compare the probability of a plaintiff winning when both parties are represented to the probability of a plaintiff winning when the plaintiff is a pro se plaintiff but the defendant is represented. In the column “Plaint Rep’d / Plaint Pro Se,” the number 2.0 would mean that plaintiffs win twice as often when both parties are represented as compared to cases in which the plaintiff is pro se. The higher the number, the better represented litigants fare relative to pro se litigants.

Next, Table 2F compares the probability of a plaintiff winning when both parties are represented to the probability of a plaintiff winning when the plaintiff is represented but the defendant is a pro se defendant. In the column, “Def Rep’d / Def Pro Se,” the number 0.5 would mean that plaintiffs win half as often when both parties are represented as compared to cases in which the defendant is pro se. The lower the number, the better represented litigants fare relative to pro se litigants.88

| % Judgments for Plaintiffs | Win Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suit Category | Cases Per Year, Thousands | Only Plaint Pro Se | Both Rep’d | Plaint Rep’d/Plaint Pro Se |

| Products Liability | 19.2 | 5% | 13% | 2.5 |

| Civil Rights | 17.9 | 2% | 18% | 11.5 |

| Tort | 16.7 | 3% | 32% | 9.8 |

| Labor | 15.5 | 10% | 76% | 8.0 |

| Government | 15.1 | 9% | 25% | 2.7 |

| Contract | 15.0 | 8% | 69% | 8.8 |

| Employment Discrimination | 14.5 | 2% | 13% | 6.6 |

| Statute | 11.2 | 5% | 64% | 13.1 |

| Asbestos | 11.1 | 11% | 15% | 1.4 |

| Insurance | 8.4 | 3% | 43% | 13.3 |

| Property | 6.2 | 2% | 77% | 42.1 |

| Financial | 6.1 | 9% | 49% | 5.3 |

| Administrative | 5.7 | 4% | 71% | 16.2 |

| Other | 14.3 | 8% | 77% | 9.9 |

| All | 176.8 | 4% | 51% | 13.7 |

| % Judgments for Plaintiffs | Win Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suit Category | Cases Per Year, Thousands | Only Def Pro Se | Both Rep’d | Def Rep’d/Def Pro Se |

| Products Liability | 19.2 | 82% | 13% | 0.2 |

| Civil Rights | 17.9 | 43% | 18% | 0.4 |

| Tort | 16.7 | 67% | 32% | 0.5 |

| Labor | 15.5 | 90% | 76% | 0.8 |

| Government | 15.1 | 84% | 25% | 0.3 |

| Contract | 15.0 | 92% | 69% | 0.8 |

| Employment Discrimination | 14.5 | 61% | 13% | 0.2 |

| Statute | 11.2 | 89% | 64% | 0.7 |

| Asbestos | 11.1 | 0% | 15% | N/A |

| Insurance | 8.4 | 67% | 43% | 0.6 |

| Property | 6.2 | 87% | 77% | 0.9 |

| Financial | 6.1 | 9% | 49% | 0.6 |

| Administrative | 5.7 | 4% | 71% | 0.8 |

| Other | 14.3 | 93% | 77% | 0.8 |

| All | 176.8 | 86% | 51% | 0.6 |

Tables 2E and 2F show that there is considerable variance in the outcomes of different types of cases for both represented and pro se litigants. When plaintiffs proceed pro se, they win somewhere between 2 and 11 percent of cases, depending on the nature of the suit. When the defendant is pro se and the plaintiff is represented, the plaintiff wins somewhere between 43 percent and 93 percent of cases,89 depending on the nature of the suit. This substantial variance is not confined to pro se litigants. Even when both parties are represented, there is wide variance in the percentages of cases won by plaintiffs, ranging from just 13 percent in products liability and employment discrimination cases to 77 percent in property cases.90 But in essentially all categories, pro se litigants fare far worse than represented litigants.

The relative win ratios tell a similar story. There is wide variance based on the type of lawsuit being brought, but represented litigants consistently have far better outcomes than pro se litigants in court. When both parties are represented, plaintiffs win at a rate between 1.4 and 42.1 times as often as when only the defendant is represented. By contrast, a represented plaintiff is roughly 0.2 to 0.9 times as likely to win a case against a represented defendant as against a pro se defendant.91

As Table 2D shows, pro se litigation comprises a significant fraction of almost all types of lawsuits in federal district courts. And as seen in Tables 2E and 2F, across essentially all of those lawsuits, pro se litigants fare dramatically worse than their represented counterparts.

III. Empirical Analysis of Pro Se Reform

A. Discussion of Data

The analysis in this Part draws upon two different sources of data. The first data source is the same dataset used for the analysis in Part II: the AO Dataset containing civil cases filed in US district courts.

The second data source for this analysis is the 2011 FJC Survey.92 The survey administrators sent two separate questionnaires to US federal district courts: one for clerks of the court and one for chief judges. Ninety US district courts responded to the questionnaire directed to clerks of the court. This analysis draws upon those responses.93

One part of that questionnaire focused on the procedural steps that clerks’ offices took to assist pro se litigants, either through programs and procedures or efforts to improve access to counsel. The survey asked about eighteen different services, programs, or procedures that at least some district courts have implemented to assist nonprisoner pro se litigants.94 The appendix to that survey describes which of the responding district courts had implemented those policies as of the survey date for fifteen of those eighteen policies.95

There are several important limitations to using this data. First, the exact date of the survey is unclear and, relatedly, the exact dates that each district court responded that it was employing or not employing these procedures is uncertain. The analysis is conducted using cases filed between 2008 and 2010. Accordingly, if a large number of district courts altered their policies shortly before this survey was conducted or if the survey was conducted substantially before the survey was published, it’s possible that this analysis would undercount the effects of those policies. In either of those scenarios, the full consequences of these reforms might not be seen in the 2008–2010 data sample. However, there is no information suggesting that either possibility is reflected in reality. Courts and commentators have been discussing and attempting to solve the challenges of pro se litigation for decades and implementing reforms for at least a decade; it seems unlikely that they all started implementing these solutions immediately prior to the survey.96

More generally, win rates are an imperfect outcome variable for evaluating the effectiveness of pro se reform, and some caution is warranted when making inferences based on this analysis. The thorniest issue is that a large portion of civil cases are disposed of in ways that do not typically result in final judgments being entered, so win rates do not directly shed light on how pro se litigants fare in those cases. Some district court reforms might plausibly result in more favorable settlements for pro se litigants, and thus improved outcomes for pro se litigants while not materially affecting the win rates of pro se litigants upon final judgment.97 That said, there is a good theoretical reason to believe that win rates upon final judgment correlate with the favorability of settlements: in typical litigation settings, if both parties have similar beliefs about the probability of winning at trial and make economically rational decisions, they ought to come to a settlement weighted to favor the party more likely to prevail at trial.98 The AO data, however, does not include any measure of settlement quality that could be used to confirm or analyze the relationship for these types of cases.

Additionally, there is no obvious way to test the consistency or validity of these survey results. If different courts implemented substantively different reforms but mapped them to the same policies when answering the questionnaire, these results may underestimate the effectiveness of certain policies. For example, if one district court allowed pro se litigants to conduct extremely formal and limited communications with pro se clerks, while another district court allowed pro se litigants who showed up at the court to receive extensive counseling from pro se clerks, both district courts may report that they provided “direct communications with pro se clerks.”99 These two policies may be sufficiently distinct that they have very different influences on the outcomes of pro se litigation. The available survey data does not provide a reliable way to tease out these types of distinctions, and they are grouped together in the analysis below. Similarly, if overburdened district courts were simply sloppy in their survey responses, this methodology may in turn underestimate the results of these policies.

Although this analysis focuses on case outcomes, those are by no means the only potential metric for analyzing the impact of pro se reforms. Another relevant, tangible measure is the length of proceedings. Pro se reforms have the potential to greatly expedite pro se proceedings, helping to ensure that litigants are able to move on with their lives as quickly as possible. Shortened proceedings are valuable in their own right without impacting case outcomes. Less tangibly, it may be the case that pro se reforms improve the litigation experience for pro se litigants and help ensure that they feel they have had a fair hearing in court. Increasing satisfaction with court proceedings is a significant benefit to litigants and also boosts the public perception of the legal system—both valuable outcomes that would not show up in the analysis below.100

Although case outcomes do not encompass all relevant information in assessing the impact or value of pro se reforms, they are nonetheless an important metric to consider. Lawyers are supposed to help their clients win cases. Accordingly, the viability of pro se reform as a substitute for better access to counsel should hinge in large part on its effectiveness at helping pro se litigants win those cases. Moreover, case outcomes are the typical metric that commentators consider when measuring the value of access to counsel to pro se litigants.101 Hence, when evaluating the tradeoffs of expanding pro se reform against expanding access to counsel, case outcomes are one of the most natural and salient measures.

B. Methodology

The following Section conducts analysis aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of pro se reforms undertaken by district courts and reported in the FJC Survey. The outcome variable is the rate at which judgments are entered in favor of the plaintiff for the types of case dispositions in which final judgments are commonly entered.102

The analysis compares differences in case outcomes in different sets of district courts. The sets are determined either by whether the district court adopted a particular pro se reform or by the total number of reforms the district court has adopted. By comparing these results, this Part attempts to determine the effectiveness of these reforms.

Unfortunately for this empirical exercise, district courts do not randomly decide whether to implement a particular reform. If these pro se reforms had been randomly assigned, then this analysis would mimic an experiment, and it would be safer to conclude (provided the statistics suggested so) that any differences in case outcomes shown in the tables below were causal. Without random assignment of pro se reforms to district courts, the conclusions of this analysis may suffer from selection bias. For example, courts that are particularly favorable to pro se litigants might also be more likely to implement reforms. If pro se litigants happened to fare better in these courts, it would be difficult to empirically discern whether litigants fare better because of the reforms or the favorable attitude, and some measure of the district court’s favorability toward pro se litigants could be an important omitted variable.

There is good reason to believe, however, that there are not major omitted variable issues in this data. There are three potential omitted variables that are important to address here, but none seems likely to be a confounding factor in this analysis.103 One key possibility is that district courts that have implemented more pro se reforms may differ from other district courts in that they have dockets with more (or fewer) pro se litigants. However, previous analysis suggests that is not the case.104 Another potentially important consideration is whether pro se reform is concentrated in a few district courts. But approximately 90 percent of district courts have implemented at least some services for nonprisoner pro se litigants, so this does not appear to be the case either.105 Finally, it could be the case that district courts typically implement either none or many of these reforms. However, similar numbers of district courts have implemented one, two, three, and four programs and procedures to assist pro se litigants;106 accordingly, there is no apparent all-or-nothing problem either.107 While this Comment does not claim that these are all of the potentially important omitted variables,108 it does seem that district court reform is a widespread practice used in different ways throughout those courts, suggesting that it is ripe for the type of analysis conducted here.109

The potential relevance of selection bias in this analysis should also be addressed. As Part II discusses, selection bias can likely explain a portion of the gap in case outcomes between pro se and represented litigants.110 However, as this Part discusses, the relevant sample for comparison is the difference in case outcomes between pro se litigants in courts that have implemented reforms and courts that have not implemented reforms. Thus, the pro se cases in different district courts are similarly affected by this selection bias. Litigants with weaker cases may be more likely to proceed pro se in EDNY, but they are also more likely to proceed pro se in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) or the Northern District of Illinois. Accordingly, the cases being compared should presumably be similar in average strength, or at least there is no reason to think this selection bias will result in differences in average case strength for pro se litigants across different district courts. These selection bias issues result in a gap in the average strength of cases brought by pro se litigants and represented litigants, but they do not lead to a gap between the average strength of cases brought by pro se litigants in two different district courts.111

C. Empirical Results

In order to evaluate the effects of different pro se reform measures undertaken by district courts, this Section compares the win rates of pro se litigants in courts that have enacted each of the reforms discussed in the FJC Survey with the win rates of litigants in the districts that have not enacted those same reforms. Table 3A compares the win rates for plaintiffs in cases in which both parties are represented with those in which either the plaintiff or defendant is pro se based on whether the district court employs a particular policy.

| % of Cases Won by Plaint | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both Rep’d | Plaint Pro Se | |||||

| Policy | # Districts Using Policy | Uses Policy? | Uses Policy? | Difference with Policy | ||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Programs and Procedures to Assist Pro Se Litigants | ||||||

| Electronic filing through CM/ECF | 36 | 47% | 46% | 3% | 3% | 0% |

| CM/ECF access to docket, pleadings, etc. | 34 | 47% | 46% | 3% | 4% | -1% |

| Direct communication with pro se clerk | 24 | 45% | 47% | 3% | 3% | -1% |

| Public info about pro se programs | 19 | 48% | 46% | 3% | 3% | -1% |

| Mediation for pro se litigants | 18 | 48% | 46% | 4% | 3% | 1% |

| Other | 14 | 49% | 46% | 4% | 3% | 1% |

| Services to Help Pro Se Litigants Obtain Representation | ||||||

| Bar-Maintained Pro Bono Panel | 6 | 48% | 46% | 2% | 3% | -1% |

| Listserv to Alert Bar of Need for Representation | 8 | 52% | 46% | 4% | 3% | 1% |

| Court Pays Costs and Some Attorneys’ Fees | 20 | 44% | 47% | 3% | 3% | -1% |

| Provision in Local Rules for Payment of Costs | 24 | 51% | 44% | 3% | 3% | 0% |

| Handout about Low-Cost Legal Services | 33 | 45% | 48% | 3% | 3% | 0% |

| Handout about Obtaining an Attorney | 32 | 46% | 47% | 4% | 3% | 0% |

| Pro Bono Panel for Pro Se Litigants | 19 | 53% | 44% | 5% | 3% | 2% |

| Local Rule Requiring Pro Bono Service from Bar | 13 | 53% | 45% | 5% | 3% | 2% |

| Court Review to Determine Need for Counsel | 44 | 47% | 46% | 3% | 4% | -1% |

Table 3A suggests that the various policies used to assist pro se litigants in federal district courts have not substantially affected win rates for pro se plaintiffs. When both parties are represented, plaintiff win rates gravitate around 50 percent. When only the plaintiff is pro se, the plaintiff win rate hovers between 2 and 5 percent. All of the policies registered in the FJC Survey classified as “programs and procedures to assist pro se litigants”—the types of policies discussed throughout this Comment—appear to have no more than a 1 percent impact on the percent of pro se litigants that actually win cases in court. Perhaps more likely, they do not actually impact case outcomes at all, and the 1 percent variation is simply noise. Regardless of whether they account for some small improvement, however, these results show that pro se reforms are not significantly moving the needle in terms of case outcomes. Any potential improvement is substantially smaller than what the experimental literature suggests would result from improved access to counsel.112 Hence, compared to pro se win rates with a lawyer, these reforms cannot be considered a meaningful substitute for access to counsel even if they yield a small improvement, at least insofar as the goal is to help pro se litigants win more cases.

In contrast, the results for services intended to help pro se litigants obtain representation are somewhat less clear. Again, the resultant “improvements” in win rates look more like statistical noise than meaningful impacts, but there is arguably more room for contrary interpretations.113 However, while those reforms are no doubt also advocated by many seeking an alternative to civil Gideon, they concern increased access to counsel instead of substitutes for access to counsel. Thus, these kinds of reforms do not resemble the types of reforms suggested by the Supreme Court in Turner nor by most commentators discussing civil Gideon alternatives.114

| % of Cases Won by Plaint | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both Rep’d | Def Pro Se | |||||

| Policy | # Districts Using Policy | Uses Policy? | Uses Policy? | Difference with Policy | ||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |||

| Programs and Procedures to Assist Pro Se Litigants | ||||||

| Electronic filing through CM/ECF | 36 | 47% | 46% | 82% | 79% | -3% |

| CM/ECF access to docket, pleadings, etc. | 34 | 47% | 46% | 82% | 79% | -4% |

| Direct communication with pro se clerk | 24 | 45% | 47% | 82% | 80% | -2% |

| Public info about pro se programs | 19 | 48% | 46% | 81% | 80% | -1% |

| Mediation for pro se litigants | 18 | 48% | 46% | 82% | 80% | -2% |

| Other | 14 | 49% | 46% | 82% | 80% | -2% |

| Services to Help Pro Se Litigants Obtain Representation | ||||||

| Bar-Maintained Pro Bono Panel | 6 | 48% | 46% | 80% | 80% | 1% |

| Listserv to Alert Bar of Need for Representation | 8 | 52% | 46% | 82% | 80% | -2% |

| Court Pays Costs and Some Attorneys’ Fees | 20 | 44% | 47% | 80% | 81% | 1% |

| Provision in Local Rules for Payment of Costs | 24 | 51% | 44% | 80% | 81% | 0% |

| Handout about Low-Cost Legal Services | 33 | 45% | 48% | 81% | 80% | -1% |

| Handout about Obtaining an Attorney | 32 | 46% | 47% | 81% | 80% | -1% |

| Pro Bono Panel for Pro Se Litigants | 19 | 53% | 44% | 80% | 81% | 1% |

| Local Rule Requiring Pro Bono Service from Bar | 13 | 53% | 45% | 82% | 80% | -2% |

| Court Review to Determine Need for Counsel | 44 | 47% | 46% | 82% | 79% | -2% |

Table 3B looks at the same questions for pro se defendants, and it tells the same story as Table 3A. Pro se defendants do not reap any more benefits in terms of case outcomes from pro se reform than pro se plaintiffs. At least for the reforms considered in the FJC Survey, none seems individually effective.

Table 3C relies on the same data but considers the win rates of different types of litigants based on the total number of policies that the district court has implemented rather than which particular policies the court has implemented. Table 3C thus seeks to test the slightly different hypothesis that there may be a cumulative benefit from implementing these policies even if none is individually impactful.

| Number of Policies Used by District Court | % of Cases Won by Plaintiff | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Both Rep’d | Plaint Pro Se | Def Pro Se | |

| Programs and Procedures to Assist Pro Se Litigants | |||

| Zero Policies | 43% | 3% | 76% |

| One Policy | 49% | 4% | 82% |

| Two Policies | 47% | 4% | 83% |

| Three Policies | 46% | 3% | 82% |

| Four Policies | 48% | 3% | 82% |

| Five Policies | 40% | 2% | 71% |

| Services to Help Pro Se Litigants Obtain Representation | |||

| Zero Policies | 41% | 2% | 77% |

| One Policy | 46% | 4% | 79% |

| Two Policies | 41% | 2% | 82% |

| Three Policies | 51% | 4% | 83% |

| Four Policies | 52% | 4% | 81% |

| Five Policies | 45% | 3% | 77% |

| Six Policies | 54% | 3% | 81% |

| Overall Average | |||

| 46% | 3% | 80% | |

Table 3C tells a similar story as Tables 3A and 3B. Although there is some variation in the win rates, there is no discernable pattern. Pro se litigants do not consistently have better case outcomes in districts that have implemented more policies aimed at improving the lot of pro se litigants. Instead, the win rates of pro se litigants deviate only a couple of percentage points from the overall average win rates for pro se litigants even in districts that have implemented three, four, or more of the policies considered in this Comment.

Overall, the analysis in this Section suggests that, though many federal district courts have implemented reforms aimed at improving case outcomes for pro se litigants, they have not yet succeeded in improving those outcomes. Tables 3A and 3B suggest that a variety of policies, each implemented in a substantial number of district courts, have all been ineffective in improving case outcomes for pro se litigants. Similarly, the evidence suggests that even courts that have implemented multiple or many of these policies have not improved outcomes for pro se litigants thus far. Despite the belief expressed by clerks’ offices and chief judges of federal district courts, commentators, and the Supreme Court that these types of measures are effective, the empirical evidence suggests that these measures make no difference in case outcomes.115

IV. Case Study: Pro Se Reform in EDNY

This Part focuses on an extensive set of pro se reforms made in the federal district court in EDNY. Because these reforms were publicly announced around the time of their implementation, this Part conducts a difference-in-differences analysis of these reforms to complement the differences analysis from Part III.116 This analysis strengthens the results in Part III, suggesting that pro se reforms have not impacted case outcomes for pro se litigants.

A. Background on EDNY Pro Se Reform

In May 2001, EDNY began one of the country’s more dramatic pro se reform programs, elevating a magistrate judge to a newly created pro se office focused entirely on overseeing pro se litigation and assigning her broad responsibilities for overseeing pro se litigation.117 These reforms were implemented with the intent to help “facilitate access to the courts” for pro se litigants.118

The EDNY pro se office has two primary functions.119 First, the magistrate judge’s pro se office—comprised of staff attorneys and administrative office employees—proposes initial orders to the assigned judge, including to dismiss or to direct the litigant to amend the complaint, and responds to inquiries from the judge’s offices about the cases. As part of these initial duties, the office gives procedural advice to individuals about filing and litigating their claims by answering questions and making forms and instructions available. Second, the magistrate judge automatically oversees all pro se cases that survive screening, handles pretrial matters, and presides at trial with the parties’ consent.120 These reforms do not exactly mimic those discussed in the FJC Survey and evaluated in the empirical analysis above. However, they do include a number of efforts similar to those evaluated in Table 3B—providing forms and handbooks as well as individual case assistance, for instance. Because this reform effort is different from those that Part III discusses, it’s hard to directly compare them. But both sets of reforms fit into a similar broad bucket: attempts by courts to improve the pro se litigation process by facilitating simpler and more convenient interactions between pro se litigants and the courts.

Although EDNY created this office partially in response to the growth of pro se litigation in that district, its caseload appears broadly representative of pro se litigation more generally as of 1999, shortly before the creation of the magistrate judge’s office.121 The concerns that led to EDNY’s decision to appoint this special magistrate judge—the difficulty of fairly and efficiently managing the large pro se docket and the need for specialized resources to do so—seem to echo the same primary concerns that other courts and commentators have expressed about the pro se litigation process.122

To date, a public, empirical assessment of the effects of this office on outcomes of pro se litigation is not available. This Part seeks to begin to fill that gap by evaluating the impact of EDNY’s reforms on the pro se process. Part IV.B discusses the methodology for this analysis. Part IV.C finds that the reforms in the EDNY have had a small, and in fact negative, impact on the win rates of pro se litigants in that court.123 This evidence, when combined with the evidence in Part III, strengthens this Comment’s finding that pro se reforms in trial courts have been ineffectual at improving litigation outcomes for pro se litigants.

It is important to note that the reforms EDNY implemented in 2001 were intended as a first step in an effort toward improving the process of pro se litigation. Moreover, the office has had more than ten years to continue innovating and revising its policy and procedures, but none of those efforts would show up in this analysis.124 The analysis below attempts only to assess the impact of the creation of the pro se office over its first five years of existence. Specific information about subsequent reforms implemented by the office is not readily available and hence not ripe for analysis. However, any such reforms may have had a different impact on case outcomes for pro se litigants and, accordingly, may indicate more promising future directions for pro se reform.

B. Methodology

In order to evaluate the impact of EDNY’s pro se reforms, this Comment runs a logistic regression using whether the plaintiff won the case as the independent variable. The dataset for this regression is all cases decided in the four New York district courts between 1998 and 2007 that involved pro se plaintiffs and represented defendants. This dataset includes 578 cases from the Northern District of New York (NDNY), 2,658 cases from EDNY, 3,843 cases from SDNY, and 668 cases from the Western District of New York (WDNY). The key variable of interest is a binary variable that is coded “1” if the case is in EDNY and filed after the implementation of the pro se reforms and “0” otherwise.125 There were 1,408 cases in this dataset from after EDNY implemented the reforms.

There are a few potential omitted variables that this analysis is unable to capture. One possible issue is changing caseloads in each district over time. If the composition of EDNY’s pro se docket shifted in a different way than New York’s other district courts in the years surrounding the reform, that may hide the impact of EDNY’s reforms. Another possibility is that noncourt legal actors may have changed their strategies in response to EDNY reforms. If, for example, outside legal aid clinics started shifting their resources to non-EDNY courts in response to this reform, possibly because those clinics knew that pro se litigants would receive adequate assistance in EDNY due to the reforms, that may also mask the impact of these reforms in EDNY. Finally, because this analysis compares the outcomes of pro se litigation in EDNY with outcomes of pro se litigation in the other New York district courts, if those district courts also made improvements to the pro se litigation process during this time period, the analysis might understate the effect of the EDNY reforms.

The regression is run with five different sets of specifications. The first regresses outcomes against a dummy for whether the case took place with EDNY reform; the second model adds a dummy variable indicating whether each case took place in EDNY; the third model adds dummy variables indicating which district court each case was filed in; the fourth adds dummy variables for the year the case was filed (but removes the district dummy variables); and the fifth model includes dummy variables for both the year and district for each case.126

By selecting the time period from 1998 to 2007, this dataset includes a symmetrical five years of cases from prior to the implementation of the reform (1998–2002) and five years afterward (2003–2007). Although the specific choice of five years is arbitrary, the essential results are robust to the length of time analyzed.127

C. Empirical Results

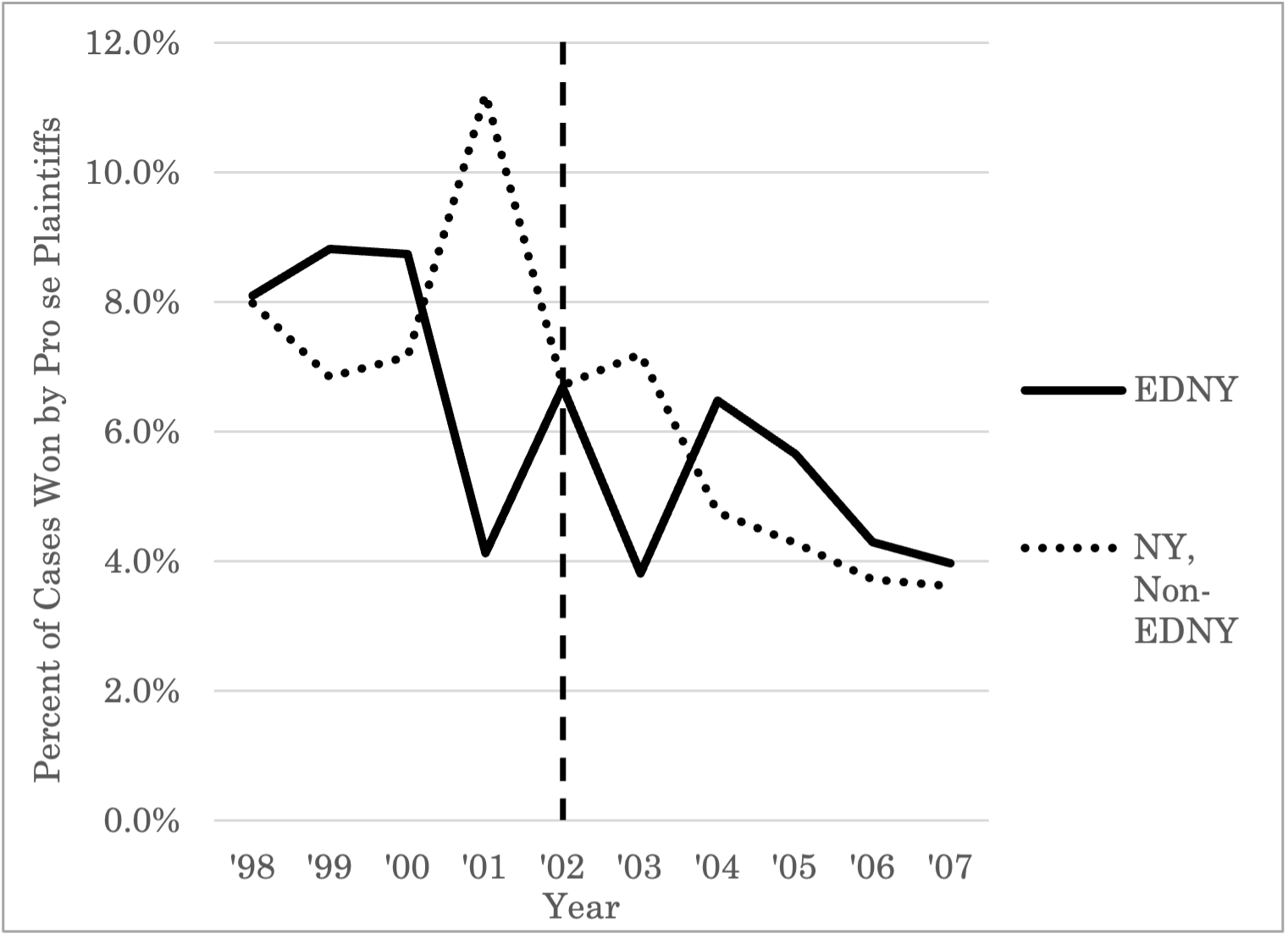

From an initial look at Figure 1, no meaningful change in the outcomes of pro se litigation in EDNY appears in the years following the creation of the pro se magistrate’s office. Instead, for all district courts in the New York area, there is seemingly considerable variance in case outcomes on a yearly basis, with pro se litigants performing very similarly on average in both sets of districts before and after the pro se reform. However, Figure 1 does reflect the possibility that the percent of cases won by pro se plaintiffs in the other New York district courts trended downward more than in EDNY. But this is uncertain. With the exception of 1999, the win rates of pro se litigants are relatively similar in EDNY to New York’s other district courts.

From Figure 1, it’s difficult to tell whether there is a trend in EDNY meaningfully different from the trend seen in other New York district courts. To investigate this further, this Comment runs the logistic regression described above. Table 4 displays the results of that regression. Because the outcome variable is whether a plaintiff wins or loses a particular case, and each of the independent variables in this regression is a binary dummy variable, the coefficients describe the change in the probability of a case outcome when the variable is set to 1 instead of 0. Hence, a coefficient of 0.5 on the variable “EDNY Reform Dummy” would imply that EDNY Reform increased the chances of a pro se plaintiff winning a case by 0.5 percent.

|

|

EDNY Reform (1) |

EDNY Reform + EDNY Dummy (2) |

EDNY Reform + District Dummies (3) |

EDNY Reform + Year Dummies (4) |

EDNY Reform + District Dummies + Year Dummies (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EDNY Reform |

-0.36 (0.85) |

-0.59 (1.54) |

-0.59*** (0.16) |

-0.015 (0.17) |

0.04 (0.24) |

|

EDNY |

|

0.28 (0.83) |

0.071 (0.13) |

|

-0.27 (0.22) |

|

WDNY |

|

|

-1.30 (0.26) |

|

-1.32*** (0.22) |

|

NDNY |

|

|

-1.36 (0.29) |

|

-1.40 (0.31) |

|

SDNY |

|

|

(X) |

|

0.00 |

|

Year Dummies |

|

|

|

(X) |

(X) |

|

Constant |

-2.61 (-0.35) |

-2.665 (-0.34) |

-2.409*** (-0.11) |

-1.894*** (0) |

-1.627*** -0.19 |

|

Observations |

7,747 |

7,747 |

7,747 |

7,747 |

7,747 |

Note: ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05

Table 4 suggests that, like the other pro se reforms that Part III considers, the pro se reforms in EDNY have not been effective in improving case outcomes for pro se litigants. The coefficient on the dummy variable indicating whether the EDNY pro se reforms were instituted is -0.59, and the 95 percent confidence interval suggests that there is some nonzero negative effect when no controls are instituted in the first model in column one.128 The results are similar for the second and third models except that, once all districts are controlled for, the negative impact of the reform is statistically significant. When dummies are introduced corresponding to the year of each case filing, this negative effect disappears and the fourth and fifth models indicate no statistically significant impact from the reform. Including the full set of controls for year and district, the 95 percent confidence interval suggests that the reforms in EDNY had an impact of somewhere between -0.43 percent and 0.51 percent on the win rates for pro se litigants, with a statistically insignificant mean estimated impact of 0.04 percent.129 These results suggest that pro se reforms were not effective at improving win rates for pro se litigants.

V. Implications

The empirical findings in Parts II, III, and IV have a number of potentially important implications for the future of pro se litigation. However, before considering the policy implications, this Comment must reiterate the limits of this analysis. First, this analysis centers only on case outcomes. Further analysis—for example, a survey-based analysis that asks litigants how they feel after they went through the litigation process—may reveal substantial benefits stemming from pro se reforms that this study does not find. Second, this analysis shows only that the reforms highlighted throughout this analysis have not impacted case outcomes for nonprisoner pro se litigants on average across courts. However, it might be the case that certain courts have been much more successful in implementing these reforms than others, and this analysis masks those successes. Moreover, limitations on survey data, coupled with the fact that litigation frequently takes years to resolve, mean that most of the data analyzed in this Comment is five to ten years old. Courts may have developed more promising innovations in the meantime, but this type of analysis would not be able to detect those benefits until most or all of the litigation begun in those years has run its course. Additionally, it’s possible that some of these reforms are significantly impacting case outcomes for prisoner pro se litigants, which may separately be an important goal of these reforms.

One important takeaway from this Comment, related to the limitations described above, is the importance of additional studies into the effectiveness of other reform measures, especially reform measures undertaken in courts other than federal district courts. As previously mentioned, other courts throughout the country have experimented with ways to help pro se litigants.130 Although the particular reforms analyzed here appear to have been ineffective, other reforms undertaken by other courts might achieve better results. With sufficient empirical legwork, successful reforms can be identified, and other courts can learn from those successes. Although courts likely attempt to learn from each other’s practices, without empirical validation of these techniques, there’s a risk that the blind are leading the blind. More empirical studies could help show the way.

Additional studies that help determine the extent to which differences in access to counsel are responsible for the gaps in case outcomes between pro se and represented litigants, especially across a broader range of types of cases, would also be useful. If differences in access to counsel explain differences in case outcomes, the legal community should be more fearful that those without adequate resources are being deprived of meaningful access to the legal system. Moreover, if communities that lack the means to gain access to counsel lack effective legal recourse, despite sometimes having meritorious claims, then the legal community should also worry that bad actors can gain by depriving those communities of legal rights without facing the deterrent effects of litigation. Concerns about exploitative employers may be heightened if more than 2 percent of pro se plaintiffs have fully meritorious claims but only 2 percent of those plaintiffs can effectively seek relief due to difficulties navigating the legal system. Conversely, if lack of access to counsel does not explain poor case outcomes for pro se litigants, perhaps the legal community should focus on other considerations, such as making pro se litigants feel that they have received a fair chance in court and had their grievances heard, rather than trying to narrow the gaps in case outcomes or provide lawyers for more pro se litigants.

Acknowledging the limits described above, this Comment does find that pro se reform in federal district courts has not yet meaningfully impacted case outcomes for pro se litigants, whereas increased access to counsel has had somewhat more promising results in the experimental literature.131 The policy implications of those facts are not immediately clear. These results suggest that increased access to counsel may help pro se litigants vindicate rights; however, the wisdom of that approach depends on whether the costs of that increased access to counsel outweigh the benefits or whether there are cheaper ways to achieve those benefits. One critical question in this vein is whether there are more effective reform opportunities available to courts, because more effective reforms could still conceivably enable improved outcomes for pro se litigants at a lower cost than increased access to counsel. This Comment finds little evidence that measures thus far implemented by courts have improved case outcomes. Hence, merely renewing and expanding similar reforms does not appear to be an especially promising path forward.

One more effective path might look toward a growing body of research on more effective ways to provide self-help resources and literature to pro se litigants. A recent article by Professors Greiner, Dalié Jiménez, and Lois R. Lupica details their endeavors to develop a theory of the issues that potential pro se civil litigants would face in the legal process. Their article then draws on recent developments in a number of fields, such as education, psychology, and public health, to imagine what truly effective self-help materials would look like and how they might help pro se litigants fare better at trial.132 Courts and commentators could try to enhance the effectiveness of their reform efforts by drawing on this and other similar research. Using this kind of research to provide effective educational handbooks or to help courts communicate in ways that are more useful to pro se litigants could enhance the types of pro se reforms analyzed in this Comment.

Finally, one other potential policy implication suggested by this Comment is that expanded access to counsel for certain pro se litigants may be an attractive option. This Comment does not fully analyze the potential costs or benefits of civil Gideon and accordingly comes to no conclusion about its overall merits.133 However, many commentators have opposed civil Gideon partially on the grounds that pro se reforms at the trial court level could be a cheaper, but still effective, alternative.134 The Supreme Court has suggested a similar belief.135 But while not totally conclusive for the reasons described above, this Comment indicates that those reforms have not had the kind of impact on case outcomes that increased access to counsel might have. Because these reforms do not yet appear to be a viable and effective alternative to civil Gideon, this Comment suggests that improved case outcomes may be better achieved through expanded access to counsel than through pro se reforms.

Conclusion

The challenges presented by the large volume of pro se cases in federal district courts may require meaningful changes to achieve a full resolution. In order to make headway on that front, reformers must properly contextualize and understand the nature of pro se litigation in those courts and evaluate the successes and failures of efforts that have been undertaken thus far.

This Comment presents commentators with a perspective on the volume, types, and typical success rates of pro se litigants in federal district courts. It shows that nonprisoner pro se litigants comprise a meaningful percentage of the federal docket. Moreover, pro se litigants show up in substantial numbers across many different types of litigation, from property cases, to torts cases, to civil rights cases. However, in nearly all of those types of cases, pro se litigants fare at least several times worse than represented litigants; overall, pro se plaintiffs are less than one-tenth as likely to win cases as represented plaintiffs, whereas pro se defendants are only about one-third as likely to win cases as represented defendants.

Moreover, this Comment assesses the effects of reforms in federal district courts aimed at helping pro se litigants. It suggests that, despite widespread optimism from numerous stakeholders in the American legal community, reforms to federal district courts intended to improve the pro se litigation process have thus far had a negligible impact on the outcomes of pro se litigation. If the goal is to improve case outcomes for pro se litigants, or to replace the potential positive impact of increased access to counsel at a lower cost, the types of reforms undertaken thus far appear to have been unsuccessful.

Appendix: AO Data Processing

The AO dataset is created and made available through the Federal Judicial Center.136 This Comment’s processing of the AO dataset closely mirrors the processing implemented in other legal scholarship.137 The dataset used in this analysis includes cases terminated between June 1988 and June 2017 as well as pending cases.

To process this dataset, first I eliminated all cases filed before January 1, 1998; the analysis in this Comment considers only cases filed after that date. After that, I dropped the following sets of cases: all cases from non-Article III district courts; all cases with a “local question” as the nature of the suit; all cases that are currently still pending and lack a termination date; all cases that have missing values for the case disposition; all observations that have missing values for the nature of the suit; a variety of cases that have a nature of suit variable indicating that the suits are of a peculiar or inconsequential variety;138 certain categories of suits that have the government as a party;139 and cases that are typically filed by prisoners and are considered “prisoner pro se litigation.”140

In addition to dropping the above cases, I undertook a series of steps to consolidate multiple records from certain cases and prevent those cases from being double-counted. To do so, I first created unique identifiers for each case based on the district, office, and docket number of its first filing. I then used those unique identifiers to consolidate multiple records that correspond to the same case into single records. I considered the filing date to be the first date on which the case was filed and the termination date to be the final date on which the case was terminated.