Welcome to the Maze: Race, Justice, and Jurisdiction in McGirt v. Oklahoma

The morning of July 9th, American Indian tribal citizens and non-Indian residents of eastern Oklahoma woke up and experienced a similar shock. The United States Supreme Court, in an opinion authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch, announced that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s reservation boundaries had never been disestablished.

The Supreme Court’s 5–4 decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma implies, though does not explicitly hold, that eastern Oklahoma is, was, and always had been within the undiminished boundaries of the Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole Nation’s reservations. The ruling was shocking and confusing for both groups of American citizens because they were experiencing a bit of what “justice” is like for the other group for the very first time.

That Thursday morning gave American Indian people a glimpse of what it must be like not to be “the Indians.” On that day, American Indians weren’t reduced to a metaphorical Red Sea, always parting to make way for White Americans’ interests. Instead, they were able to win despite those interests and without the indignities that have become the norm in the Supreme Court’s Indian law opinions.

That same morning gave the non-Indians of eastern Oklahoma a glimpse of part of the Indian experience: waking up to helpless confusion about what the United States government has just done to your lands and rights, followed by the even greater problem of trying to understand the confusing jurisdictional rules that have been the status quo in Indian Country for a long time.

At times like this I think that Lady Justice must have a sense of humor.

I. The Confusion of Victory and Dignity at the Supreme Court for American Indians

McGirt was a case, like many before it, about whether an Indian tribe could count on the law: whether a promise is a promise and whether the word of Congress or the courts should be as reliable and valuable to American Indians tribes as it is to any other American citizen or government. Justice Gorsuch’s bold proclamation at the outset of the opinion that the Court would “hold the government to its word” seems to be a direct response to Justice Hugo Black’s famous dissent from sixty years prior: “I regret that this Court is to be the governmental agency that breaks faith with this dependent people. Great nations, like great men, should keep their word.”

The law was clear: the Muscogee (Creek) Nation should win in McGirt because its reservation boundaries had never been clearly disestablished by Congress. McGirt was nearly indistinguishable from the recent unanimous decision in Nebraska v. Parker, in which Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that nothing short of a “clear textual signal” could support diminishment.

Yet before the decision, Indian law experts, practitioners, and many American Indian people remained skeptical. Tribes have been “supposed” to win before. But doctrines always seem to change just in time for Indians to lose. Especially when there are large non-Indian interests at stake—as there were in McGirt. As fellow Indian law scholar Professor Gregory Ablavsky described: the real issue in McGirt was that Nebraska merely decided the fate of little Pender, Nebraska, and “Tulsa is not Pender.”

It is not an accident that non-Indian interests tend to determine outcomes in Indian law. It points to a clear pattern in Indian law doctrine: the Supreme Court frets over the fate of non-Indians’ rights and property, while tribes are denied the consistent protection of American law. And so McGirt staked out what kind of “justice” the Indian tribes could expect from this new Supreme Court.

The dissenting justices favored reviving an older approach in diminishment cases, which placed significantly more weight on subsequent behavior, including demographic change to a reservation, as proof of its disestablishment. Or as the dissent, quoting Solem v. Bartlett, describes this test, diminishment should turn on the “Indian character” of the land. There is no analogous concept for evaluating the “character” of any other sovereign’s land. Indeed, it is impossible to imagine one. When American citizens move into the territory of American states, or counties, for example, their citizenship base just expands. Migration is not usually evidence of a government’s dissipation, it is usually evidence of its expansion.

But American Indian tribes have not been treated like governments should. Tribes lose because they are the Indian sovereigns. A racialized and often grotesque body of law has long controlled the determination of tribal sovereigns’ rights and powers. The story of tribes going to the Court often involves them acting like any other government, and being told they can’t do that because they are Indians. Take, for example, United States v. Rogers, where Supreme Court denied tribes the right to freely naturalize citizens because of the racialized lens it saw them with. No matter what the tribe says, “white men” could not, according to the Court, be “adopted” by a tribe and “become an Indian.”1 Nor do tribes enjoy the simple power to enforce their laws on all the persons who freely enter their territory. In Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, the Court held that “[b]y submitting to the overriding sovereignty of the United States, Indian tribes therefore necessarily give up their power to try non-Indian citizens of the United States….” A clear double standard with the States, but tribes aren’t states, they are Indians and the Court sees their sovereignty as fundamentally limited by their race. The Oliphant court says non-Indians, instead of non-tribal-members or non-tribal-citizens in this passage, because it sees tribal government sovereignty as tied to—and limited by—its racial status as an “Indian” tribe.

The dissenting justices are correct that the “Indian character” doctrine played a larger role in earlier cases before Justice Thomas’s 2016 opinion in Nebraska v. Parker, where the Court began emphasizing the law’s text takes priority.2 But, as Justice Gorsuch explained in McGirt, there are good reasons why this “Indian character” test should be set aside, and why it is something we should be ashamed was ever law:

[J]ust imagine what it would mean to indulge that path. A State exercises jurisdiction over Native Americans with such persistence that the practice seems normal. Indian landowners lose their titles by fraud or otherwise in sufficient volume that no one remembers whose land it once was. All this continues for long enough that a reservation that was once beyond doubt becomes questionable, and then even farfetched. Sprinkle in a few predictions here, some contestable commentary there, and the job is done, a reservation is disestablished. None of these moves would be permitted in any other area of statutory interpretation, and there is no reason why they should be permitted here. That would be the rule of the strong, not the rule of law.

That the Court rejected the “Indian character” test was incredible. That it also explained what that test did to take subsequent violations of tribal rights and, in fact, retroactively read them into the law, was powerful. That it called this doctrine little more than a double standard whereby tribes alone were forced to accept “might making right” was justice.

Such justice and a nod to how the Court’s own doctrine mistreated Indian tribes is completely new to Indian tribes. So new and foreign that it was, and still is, confusing.

Far from expecting to be treated fairly and with dignity, Indian tribes have come to expect the opposite from their nation’s highest court. Previous Supreme Court opinions have made clear that tribal sovereignty has been eroded and tribal governments have been denied the consistent protection of American law partially because they were judged as “the other” or otherwise unworthy to survive as robust contemporary governments in the United States. Indian law opinions are filled with the rhetoric of savagery and discussion of how the uncivilized status of tribal governments warranted a lower status within the United States.

These opinions are not mere rhetoric or the relics of times long past. These legal justifications for the erosion of tribal sovereignty are recent memories and still good law. They haunt those of us whom they are about. In United States v. Sandoval, the Supreme Court granted my great-grandparents and our tribe “Indian” status because it judged them to be sufficiently uncivilized: “[C]hiefly governed according to the crude customs inherited from their ancestors, they are essentially a simple, uninformed, and inferior people.” Also maddening is how much of what the Court has said about tribes as it strips their powers is demonstrably false. The Oliphant Court justified stripping tribal courts of criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians in part because their inherent inability to prosecute non-Indians would be “obvious a century ago when most Indian tribes were characterized by a ‘want of fixed laws [and] of competent tribunals of justice.’” However, if you read the 1834 Congressional Report cited for this point, it says quite the opposite, on the very same page cited by the Court:

The right of self-government is secured to each tribe, with jurisdiction over all persons and property within its limits, subject to certain exceptions, founded on principles some-what analogous to the international laws among civilized nations. Officers, and persons in the service of the United States, and persons required to reside in Indian country by treaty stipulations, must necessarily be placed under the protection, and subject to the laws of the United States….As to those persons not required to reside in the Indian country, who voluntarily go there to reside, they must be considered as voluntarily submitting themselves to the laws of the tribes. H.R. Rep. No. 23-474, at 18 (1834).

If anything is obvious, it is that the Court has a history of eroding tribal sovereignty based upon concerns about non-Indian interests and convenient fictions about history and about Indians.

In its briefing before the Court, the state of Oklahoma wanted to take advantage of this dynamic, saying that a decision in favor of the tribe would be a “seismic” change to civil and criminal law in the state that would “plunge eastern Oklahoma into civil, criminal, and regulatory turmoil.” It is tried and true fearmongering to suggest that the sky would fall and there would be complete lawlessness for non-Indians under tribal rule or reservation status. At some points, it seemed like the fearmongering might have worked. At the first oral argument, Justice Stephen Breyer asked about what would happen to “1.8 million people” who had built their lives on everything down to “dog-related law.” To Indian law experts the question was absurd. Under Montana v. United States, the tribes may regulate non-member conduct on reservation land if the conduct stems from a “consensual relationship[ ] with the tribe or its members” or directly affects “the political integrity, the economic security, or the health or welfare of the tribe.” Especially given how narrowly the Court has subsequently interpreted the Montana test, I cannot think of a factual scenario under which a tribe could justify regulating dog-law as a threat to its political integrity, economic security, or health and welfare that doesn’t sound like the plot of a science fiction film where dogs become super-spies trained to infiltrate Tribal Council meetings. That the Court, for once, didn’t take the bait was refreshing.

The resounding cry of joy that went up throughout Indian Country was because it still feels so improbable that tribal governments can win simply by relying on the word of the United States—whether the promises of a judicial doctrine, those within a treaty, or both. After all this time, to simply be sovereigns and people who are treated not as threatening, inferior, or standing in the way of “real” American interests, but simply American citizens with a viable claim that is worth something in a court of law, is a moment worth celebrating.

Time will tell whether the Supreme Court can maintain the new and confusing faith in the law that it has momentarily earned from its American Indian people.

II. The Confusion of Indian Country’s Justice for Non-Indian Eastern Oklahoma

American Indian people know very well what it’s like to wake up one morning and learn that the federal government has shifted the ground under your feet. It’s a bizarre helplessness, finding yourself desperate to make sense of the new set of rules that govern your life and concerned for the future of your rights under the rule of a new government. This is certainly what happened to many people in eastern Oklahoma after the McGirt decision was announced.

Eastern Oklahomans had no real cause to worry, but they certainly had been made to worry. As discussed above, the state of Oklahoma vastly overstated the implications of the case and argued that this holding would “drastically change[ ]” the “lives” of “1.8 million Oklahomans.” But the reality is that very little would change. The tribe only has civil law jurisdiction over non-members in narrow circumstances. Even within Indian reservations, the state retains exclusive jurisdiction over all non-Indian on non-Indian crimes, which we can assume will continue to be the vast majority of crimes in the territory and most of the prior convictions affected.

After McGirt, the state of Oklahoma backpedaled furiously to calm its citizens concerning everything from public safety to taxes, which were still due the following week. The attorney general of Oklahoma gave a news interview to explain the impact of the decision. When asked about the “hysteria” and “fear,” he reassured the public that they “should not” worry. What he then went on to do was something all too familiar to Indian Country: he struggled to explain even a bit of the complex rules governing jurisdiction in Indian Country. Although Indian law experts agree that very little will change in the lives of the majority non-Indian population, to understand why, you would have to explain all of federal Indian law doctrine, which is about “as incoherent as it is complicated.” Or else, you can just stick to the rules that the law has created for how jurisdiction will work, but those are also complicated. The civil and criminal jurisdictional rules governing Indian Country are so complicated that they’re commonly described as a “maze.” As an Indian law scholar who has a laminated chart explaining criminal jurisdiction on my desk, and as a former Indian Country resident, I couldn’t help but chuckle. Watching the attorney general try to simplify things was all too familiar. I thought, “Confused? Welcome to Indian Country!”

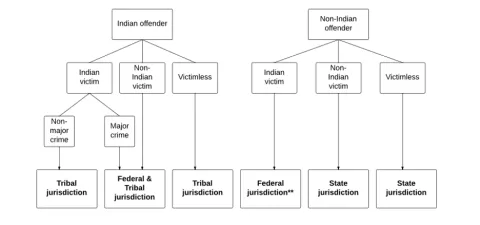

Putting aside civil jurisdiction—because it’s so case specific—let’s just try to work through the realities of criminal jurisdiction. To begin to grasp this complicated system, you need a chart that breaks down the Indian status of both the defendant and the victim, as well as the seriousness of the crime, to determine whether the state, tribe, or federal government may have exclusive or concurrent jurisdiction to investigate and prosecute the crime.

The chart for assessing jurisdiction looks like this one, taken from the Indian Law and Order Commission Report of 2013:

Of course, none of these facts come together all at once. Imagine trying to figure all of this out as the dispatcher who answers a call, the cop who arrives at the scene, or the judges, defense counsel, or prosecutors who are presented with a limited set of evidence. In Indian Country, all of these actors must navigate this jurisdictional maze on top of their job, knowing that the result of the maze may mean they are the wrong person for the job or that the whole case could get thrown out.

And the chart above is just the basic framework. The asterisk for non-Indian offenders and Indian victims under federal jurisdiction actually notes that tribal governments can opt into jurisdiction over non-Indians who commit certain kinds of crimes and have certain ties to the tribe, but only if the tribe provides certain kinds of procedural safeguards under the 2013 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) (there is another chart for this).

Tribal, state, and federal law enforcement in Indian country have developed entirely new kinds of processes for answering these questions. Some tribes, like the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, have developed preliminary tribal court jurisdictional hearings to determine Indian status and for their VAWA prosecutions also whether non-Indians have adequate ties to the tribes and there is probable cause they have committed one of the domestic or dating violence offenses over which the tribe has jurisdiction. In many instances, tribal police’s first question—even before “what happened?”—becomes: “Was it in our jurisdiction? Was the perpetrator Native American?”

It is hard to defend the status quo of this jurisdictional framework. It is not desirable, successful, or even administrable. It is—to put it bluntly—confusing as hell. No one would design a justice system this way. Legal scholars have criticized this system for decades, not just because it is confusing, but because it has created real danger in Indian Country, where crime escalates because it is so hard to prosecute. Tribal governments have generally pushed for more authority over their lands both because they want more sovereignty but also because these rules are so difficult to navigate it has become dangerous for their citizens, especially those who are left to wait on federal prosecutions that never happen.

Tribes are the local government, but they are often powerless and unable to respond to what are, in many instances, local problems. Crimes involving their citizens but non-Indian defendants are exclusively federal. Even when tribes do have the power to prosecute, they remain dependent on the federal government to adequately police and prosecute serious crimes. Tribal courts are limited in the fines and sentences that they can impose under the Indian Civil Rights Act, as amended by the Tribal Law and Order Act. Tribes are only able to impose a maximum fine of $15,000, and only able to sentence offenders to a maximum of three years of incarceration per offense, and a total of nine years for consecutive sentences—no matter how serious the crime is.

This is especially frustrating as the federal government admits its track record in Indian country is a colossal failure when it comes to adequately funding the infrastructure needed to police and prosecute in Indian Country. The federal government has declined to prosecute around 40 percent of the Indian Country crimes that are referred to it consistently for the past ten years, and that is an improvement from the prior decade. Amnesty International called this a “maze of injustice” with particularly devastating effects for Native American women.

This mess is particularly inexcusable because the rates of violence in Indian Country are staggering. According to a 2010 Report from the Department of Justice, 84.3 percent of Native women, and 81.6 percent of Native men experience violence in their lifetime, and about one in three reported experiencing violence in the past year. Moreover, the same study found that 90 percent of Native women and 85 percent of Native men experience intimate partner violence from non-Indians, precisely the demographic that the “maze” currently makes it the most difficult to prosecute. The United States Commission on Civil Rights has pointed out two occasions in which underfunding combined with this jurisdictional maze has created nothing short of a civil rights crisis in Indian Country.

Despite the mountain of evidence that the current system is a disaster for the public safety of Native people—especially Native women—on reservations, tribes have been largely unsuccessful at pushing for changes to this framework in Congress. Tribes have been asking for an Oliphant-fix to restore their jurisdiction over non-Indians since it was decided in 1978. The one, somewhat frustrating exception, is that after the Supreme Court’s decision in Duro v. Reina that tribes likewise lacked the ability to prosecute non-members Indians, the next year Congress passed a legislative fix restoring tribal jurisdiction over other Indians. There was some pushback from a few U.S. senators concerned about non-members who lacked representation in tribal court or the protection of constitutional rights, but politicking quickly overcame these concerns and a permanent Duro fix was passed. This is in stark contrast to the efforts to get an Oliphant fix, where the concern with how to protect the rights of non-Indian defendants dominates. Only recently have tribes been able to gain back a bit of their jurisdiction over non-Indians with VAWA 2013. This tiny step meant a lot to tribes and domestic violence victims, but did little to change the overall system. It is hard not to look at this history and again see a familiar pattern in Indian law: concern for non-Indians controls Indian law.

The Indian Law and Order Commission Report of 2013 sweepingly condemned this jurisdictional mess and called for tribes to be able to adopt the “American way” of local-governance law enforcement by opting out of the mess into the ability to prosecute all persons and crimes in their territories as long as they provided equivalent U.S. Constitutional rights protections. It likewise called for the creation of a new Federal Circuit Court of Indian Appeals. It went nowhere. The status quo of a fundamentally confusing and largely inadequate justice system for the 1.3 million people (as of 2010) who live on Indian reservations has not particularly worried Congress in the past.

The Commission’s recommendations remain a good idea. The success of tribal prosecutions under VAWA demonstrates both how tribal governments are capable of providing adequate process and that there are systemic offenders in Indian country who can be finally brought to justice by local police who are willing and able to protect their citizens. The pre-Oliphant status quo in which tribes were able to, at the very least, able to—like any other government—prosecute anyone who committed a crimes on their land—especially against one of their citizens—is a bare minimum step in the right direction. But I won’t hold my breath waiting for Congress to care more about what happens to Indians.

But on July 9th, the Supreme Court did something that might change everything. With McGirt, by my best estimate, the Court doubled the number of American citizens who live in Indian Country. Most interestingly, it added 1.5 million non-Indians to the pot of people who must deal with this mess. And, as discussed above, both Congress and the courts have a record of caring enough about non-Indians being stuck in a seemingly unfair legal system to rework Indian law.

We should watch closely to see how the negotiations between the Five Tribes, Oklahoma, and Congress play out, and how non-Indian law enforcement and citizens navigate this new reality. Oklahoma is in the maze now. Non-Indians will come out on the other side of the maze without much changing in the outcome of which government has jurisdiction over them, but they will have to navigate it none the less. The maze of overlapping justice systems will be, at the very least, inconvenient and confusing for many non-Indians. It will also be uncomfortable and particularly frustrating for Oklahoma law enforcement and courts who, I expect, will not enjoy having to constantly assess Indian status.

What’s more, reservation status may bring in additional federal regulations—and potentially even tribal regulation (and taxation)—not of non-Indian private individuals (or dogs), but of powerful industries like oil and gas. Combined with the state’s presumed inability to tax tribal members on their reservation lands, this gives the tribes a lot of economic bargaining power in negotiations with Oklahoma about what kind of reforms they would like to take to Congress. It also gives the tribes capacity to impose additional taxes on a much larger population of tribal members themselves, which could support the provision of even more service they already have the capacity to provide. The Muscogee (Creek) Nation alone operates with an annual budget of $300 million based on its current revenue sources. That’s already half the budget of the City of Tulsa. These Oklahoma tribes are ready and able to do far more governing in their territories, and it would make things much simpler if they were allowed to do more.

Imagine if, in a final twist brought about by McGirt, the jurisdictional system finally becomes more navigable and less confusing for Indians, thanks, ironically enough, to non-Indian interests. We can only hope that the parties involved choose to see the situation as an opportunity to work together to agree on a system that finally cuts through the jurisdictional confusion and allows, at long last, for justice.