Slicing Defamation by Contract

Slices and Lumps is a recipe book for thinking. Using a deceptively simple analytical framework, the book showcases the power of conceptualizing the world through the prism of “slices” and “lumps.” As Professor Fennell shows, the level of granularity of legal rights and duties—how lumpy they are—can have a marked impact on behavior, which presents another lever for policymakers to pull. Through dozens of examples and discussions, this book provides a vivid illustration of how much insight can be gained by thinking about longstanding problems as problems of optimizing their “lumpiness.” In this short contribution, I will follow the book’s recipe and offer a quasi-policy proposal, quasi-thought-experiment in some of my areas of interest: contracts and torts.

Even at a high level of abstraction, conceptualizing torts and contracts through the prism of slices and lumps reveals important differences. Tort law tends to be lumpy—either the pedestrian was trespassing or not; either the driver was negligent or not; either the factory polluted or not—whereas contract law offers an almost limitless granularity. Indeed, contract law’s ideology is of the freedom to assemble rights and duties from a broad and minimally restrictive menu of options. Consequently, where torts scholars wield a hammer with which they bang on social nails, contracts scholars grip a scalpel. Against this background, I develop here the idea that the tort doctrine of defamation law is too “lumpy” and that defamation law would better achieve its goals if it were “sliced” by contract law. While space limitations prevent me from making the case in full and addressing many possible objections, I hope to dissect enough aspects to motivate a detailed investigation of this idea.

But first, let me motivate my inquiry with the story of Mel Mermelstein. The year is 1980, and the then 54-year-old Auschwitz survivor encountered a public advertisement from the Institute for Historical Review (IHR)—a hate organization operating under a pseudo-academic guise. In the ad, the IHR denied the fact that the Nazis used gas to murder Jews and other minorities. To clothe its message with credibility, the IHR offered a prize of $50,000 to whomever could bring contrary evidence. Mermelstein, who witnessed first-hand the horrors of the Nazi genocidal machine, did exactly that. He approached the IHR with evidence and demanded that it pay for the false assertion. Not to anyone’s surprise, the IHR refused to pay. Mermelstein brought a lawsuit in 1983; the IHR lost and settled for a payment of $90,000 and an issuance of an apology. This outcome tarnished any claim to credibility the IHR had. And while they did not stop making inflammatory statements, the absence of similar financial offers is quite palpable.

In the Mermelstein case, defamation law was mostly irrelevant, as it does not protect groups. For precisely this reason, however, Mermelstein’s story carries interesting lessons for defamation doctrine. We see here, for one thing, how the fact that the statement was not actionable created a credibility problem. Cheap talk is empty talk: It is hard to establish credibility when there is no penalty for lying. This alludes to defamation’s law greatest, yet underappreciated, benefit: lending credibility to speech. It also demonstrates how there are incentives to bridge this gap—to create liability privately when the law fails to do so for the parties—and that private parties may assume potential liability voluntarily. And finally, it shows how credibility is bought at the price of falsification—you can only build credibility by exposing your statement to verification and repercussions. Here, Mermlestein’s response vindicated the truth and helped expunge the veneer of respectability the IHR claimed.

These lessons are timely, as large reforms to defamation law are on the horizon. To understand this future, remember the past: defamation law started as a common-law protection for the reputation of victims of false derogatory speech. The doctrine protected victims through three channels: (1) the deterrent effect of defamation law; (2) redress in case of injury; and (3) vindication of truth in a public forum. In the seminal case of New York Times v. Sullivan, the Supreme Court held that reputation-protection must be balanced against the free speech rights of potential speakers, especially when statements concern public figures. This decision and its progeny led to an environment where media outlets receive broad, although not unqualified, protection from defamation. Recent calls, however, seek to upend this longstanding balance. While the national conversation became embroiled in debates over fake news, Justice Thomas has expressed an intention to revisit New York Times v. Sullivan, a new defamation Restatement was announced, and President Trump has continuously called to expand defamation laws:

“We are going to take a strong look at our country’s libel laws, so that when somebody says something that is false and defamatory about someone, that person will have meaningful recourse in our courts.”

Expanding defamation law will exact a price. Strict defamation laws mean tighter regulation by the courts of speech and the press, the inevitable chilling of free speech, and, some argue, amplification of the harmful effect of fake news. Given these threats, it is pressing to evaluate whether there are alternative means of confronting concerns of fake reporting and false allegations without jeopardizing free speech, free press, or liberty.

Thinking through the prism of lumps and slices helps us to see a better way forward: Defamation by contract. I propose here the application and development of a legal tool called “Truth Bounty,” which will allow parties to slice defamation law’s current tort liability. A truth bounty is a device, not unlike the one used by the IHR, which allows journals and journalists to stipulate a reward, as a bond, to any member of the public who can substantially falsify a story, in accordance with established procedures and standards of proof. Critically, the truth bounty will come in addition to whatever liabilities the media has under existing defamation law and is meant only to replace the proposals to expand media liability through tort liability.

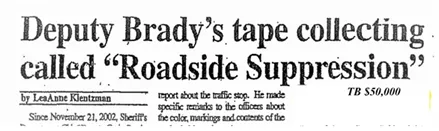

The implementation of truth bounties is designed to be as simple and straightforward as possible. Taking a cue from the UCC and the Incoterms, who use abbreviated notation as a shorthand for complex procedural arrangements, the procedure of a truth bounty can be triggered by the simple “T.B.” and the dollar amount that is at stake. So, for example, next to the story about a corrupt politician, a short notation can be appended “T.B. $50,000”; as the following figure (featured in the case, Klentzman v. Brady) illustrates. This notation will be enough to trigger the bounty and allow any member of the public who can disprove the story to claim the $50,000 prize

By providing such bounties, journals can garner credibility and, thus, readership, distinguishing themselves from unreliable sources. In some sense, the bounty is akin to a contractual warranty, but rather than a warranty of the washer’s engine, it is a warranty of truth. The choice of the bounty itself will be at the discretion of the editor and will depend on a combination of the confidence they have in the story and its sources and commercial factors. Of course, some journals may only post a nominal bounty, which might seem, at first blush, as a loophole. Suspend, for a moment, the disbelief in truth bounties and imagine a social equilibrium where bounties are commonplace. When an editor decides to “deviate” from this equilibrium by posting a low bounty, it looks bad. It immediately alerts the audience that this story is likely bogus, badly researched, or tentative. The deviation, then, comes at a palpable price—to the story, the editor, and the journal. And even if the editor of, say, a tabloid is willing to pay this price and runs the story with a nominal bounty, the audience is on high alert that this story is dubious. This takes most of the sting from the publication, leaving the victim’s reputation largely intact—all of that without even filing a lawsuit.

Are truth bounties realistic? Would journals and editors have an incentive to post truth-bounties? For the most part, the answer seems positive. This may strike some as counterintuitive— why would any publication risk legal-financial liability voluntarily? But the reality is that under defamation law, media outlets are already assuming (some) legal risk for every publication (some more than others), if it pans out as false. Worse, the tort imposes an especially costly liability because of the inherent uncertainty of the victim’s provable harms in court. When the NY Times runs a story about an alleged sexual predator, for example, it is very difficult to anticipate the victim’s recovery—how much business he will lose, what emotional harm he will suffer, etc. This uncertainty is compounded by the regular use of additional punitive damages in this domain. This means that, if found liable, the journal may have to pay millions in compensation. Yet, despite these costs, media outlets regularly publish stories. Interviews with reporters and editors reveal that editors value credibility greatly and, in fact, censor many stories today to avoid loss of reputation. Truth bounties allow reporters to garner credibility and exposes them to a bespoke and known risk of liability.

What is the social case for truth bounties? Truth bounties are, first and foremost, a signaling device. The journal has private information about the reliability of any given story, which is a function of the number of sources consulted, the sources’ reliability, the rigor of the editorial process, the private motivations of sources to share information, the story’s timing, among other factors. While there are many ways in which a journal can communicate its confidence in its stories, there is no more time-honored tradition than putting one’s money where one’s mouth is. Admittedly, even under tort liability, one signals confidence by running a story, as doing so exposes one to liability. The difference is not in signaling per se; both the crow and the nightingale can sing. It is the quality of the signal that makes all the difference. By slicing the truth bounty, the journal can tailor its degree of confidence to the specific story, thus harmonizing the signal and the editor’s confidence in it.

And here is another reason to like truth bounties: they crowdsource the search for truth. Under truth bounties, every member of the audience can claim the prize by disproving the allegation. Often, it will be the victim herself who would be in the best position to claim the bounty, for she will have private information of her innocence. But sometimes, it will be others who will have better access to relevant evidence. If the story alleges that a person committed a crime in Indiana, a store clerk may be able to provide an alibi from the store camera in Mississippi; or if the story alleges that an actor sexually harassed the camerawoman, she might be able to show that they had a consensual relationship. By awarding the bounty to any member of the public who can substantially disprove the story, we encourage the public to share private information and help with the search for truth. While the target may not receive compensation the way she does under current law, truth bounties protect the victims in three ways that are in some ways stronger. First, when a bounty is claimed and this fact is advertised, then the victim’s name will be vindicated. Second, she can gain access to vindicating information she might not otherwise have. While some witnesses may share evidence voluntarily, many remain passive; the incentive created by truth bounties may propel them to come forward. Third, the incentive to wrongfully defame in the first place, given these two considerations, will be diminished.

Truth bounties would also encourage the publication of more stories. If we were to expand liability through lumpy tort liability, every story will expose the paper to a risk of liability of unknown value. The journal will run a story only if the benefits exceed this lumpy cost. This means that on the margin there are some stories that would have been published, had the level of liability been slightly lower. As Fennell notes, “Lumpier choices render intermediate alternatives unavailable and thereby force parties to all-or-nothing (or lump-or-nothing) decisions”—the journal is limited to choosing between publishing a report and assuming all liability or abandoning it altogether. True, publishing these marginal stories means publishing stories that are less reliable than others. To some, this would be a benefit; stories about powerful people like Harvey Weinstein have been floating for a long time but were never published. An earlier publication of these rumors may have been helpful in bringing an end to a series of sexual assaults. Others, however, might worry that such stories could significantly harm their subjects. This concern is assuaged, although not eliminated, by the observation that the harm to victims is lower under a ‘slicey’ system than it would be under an expanded lumpy tort one. The tort liability is very lumpy, making any published story even more credible because the magnitude of liability is larger. For these stories that would be published, the victim is actually better off under a low truth bounty than under a lumpy tort liability.

But perhaps the most compelling argument for defamation by contract is the argument against defamation by torts. Inasmuch as the policy alternative is the expansion of defamation laws to include media outlets, this expansion will come at a palpable price to the freedom of the press. England, for comparison, adopted a strict defamation law. It has since been shunned by many publishers who worry that publishing there would lead victims to engage in libel tourism—forum shopping for favorable defamation laws. This chilling effect on publishing is a real cost to the marketplace of ideas and basic freedoms alike. Expanded tort liability puts a special strain on smaller outlets and investigative reporting, as it imposes a very lumpy cost on them. Expanding defamation law across the board, as is now proposed, would prove considerably more onerous than truth bounties, with worrisome anticompetitive effects on smaller outlets. In this, then, the voluntary use of truth bounties can expand accountability without jeopardizing the freedom of the press.

And, at the risk of exhausting the reader’s patience, here are two final reasons to care about truth bounties. A world where truth bounties are common, as alluded before, is a world with a clear separating equilibrium between high-quality and low-quality journals. That is, it will be easier to distinguish real, valuable reportive journalism from other forms of infotainment. And, if the truth bounties procedures include an escrow account, bonds, or insurance, they can also overcome the judgment-proof problem associated with “shallow-pocket” journals.

If truth bounties are all that, why is it that we don’t see them used more often? A leading reason is enforceability. Professor Daniel O’Gorman recently examined with great attention the enforceability of a special kind of contracts—the ‘prove me wrong’ contracts—which are very similar to truth bounties. Under these agreements, the offeror is offering a payment to any person who can prove them wrong; one familiar example being the Carbolic Smoke Ball case, where a prize of £100 was promised to whomever could prove wrong the seller’s advertisement that directed use of their esoteric drug would prevent the flu. A lady contracted the flu despite following the seller’s instructions and then brought a successful lawsuit. O’Gorman believes that, in general, such cases fail to satisfy the consideration requirement, for the offeror does not derive any benefit from being proven wrong. While in the Carbolic case one could argue that the seller was selling some kind of warranty, the case for consideration is more difficult with truth bounties–as these can be claimed by any member of the public, even if they did not purchase the newspaper or relied to any extent on the truth bounty. Now, I would resist the idea that the consideration tail should wag the contractual dog. I also don’t think that the inducement test under the bargain theory should at all be concerned with whether the induced action is a benefit conferred upon the promise. Suffice it, in my view, that it is objectively determinable that the promise was meant to induce action or at least a promise of action.

In any event, there is a more substantial enforceability hurdle, as demonstrated by the odd case of Kolodziej v. Mason. A defense attorney appeared on TV and argued that his client couldn’t have traveled from the location of his last sighting to the scene of the grisly murder within the time available to him. In making this claim, the lawyer added “I challenge anybody to show me—I’ll pay them a million dollars if they can do it.” An entrepreneuring law student (who else?) took the challenge. He replicated the trip and showed that it could be done in time. But the lawyer refused to pay, and the case was litigated. The judge ruled that there was no contract as the lawyer’s statement was indefinite and hyperbolic, comparable—the judge explained—to stating “I’ll be a monkey’s uncle.” And so, the judge refused to enforce a relied-upon proposal, made by a lawyer on national television, that contained both a price and detailed offer of service.

While Kolodziej does not bar the possibility of agreements that would meet this high enforceability threshold, it does make it more costly and uncertain. Daniel Hemel and Ariel Porat highlight how such costs can easily be prohibitive, as beyond formalizing the offer, the offeror also needs to design relevant procedures for the refutation process—for example, the standard of proof, judge, and choice of law—and then educate the public about them. They also identify another cost of offering a prove-me-wrong contract: It just doesn’t feel right. It appears that making such offers sometimes violates a social norm and makes the offeror appear crass or tone-deaf to social conventions. Hemel and Porat bring the example of presidential candidate Mitt Romney, who appeared out of touch when, in a public debate, he offered to pay $10,000 to Rick Perry if the latter could prove his allegation that Romney supported a nationwide health insurance mandate.

How can we implement truth bounties and slice tort liability? The challenges just presented hold the key. What would be imperative is the creation of an off-the-shelf, turnkey solution, that journals could use at a low cost and courts would reliably enforce. Doing so requires little infrastructure and it can be legislated into existence or even introduced to the new Restatement project, as a voluntary option. The use of designated code word, such as T.B. or Truth Bounty solves a few problems simultaneously. It is not an expression , so it will be easy to verify intent. This should give courts the confidence necessary to enforce these agreements. The use of special language invokes not just a general commitment to pay, but also, willingness to be bound by the specific procedures the truth bounty institution entails. For reasons explored shortly, it will not take long to educate the public on the meaning of this special term. Finally, the conciseness of the term makes its invocation simple, unequivocal, and cheap in terms of print real-estate.

The procedures involved in claiming the bounty should be standardized and carefully developed. Some questions of choice of forum (and in particular, litigation or arbitration), choice of law, standard of proof, escrow, division of bounty among multiple claimants, and so on must be thoroughly analyzed in a way that space does not permit here. In particular, we should think about the necessary level of proof to disprove a story and how retractions (or bounty claims) should be advertised. However, I suggest that none of these issues present an insurmountable challenge; many of the procedures used to prove defamation in courts today can be adopted and a broad range of alternatives would achieve the goals of truth bounties. After creating this instrument, the goal would be to promote its adoption. With a widely adopted truth bounty norm, it will be difficult for journals to deviate without disclosing their lack of confidence.

But getting journals to adopt this policy is admittedly difficult and presents some first-mover problems. Still, if the alternative is the mandatory expansion of libel laws, at least the major outlets can be encouraged to set the standard by example, leading to a cascading effect. Another challenge consists of educating the public on the meaning of truth bounties. But this, too, does not appear very difficult. Libel stories tend to be high profile and seeing that media outlets have an incentive to advertise their reliability, much of the message can be trusted to disseminate organically.

Whether or not I was able to persuade in the viability and desirability of truth bounties, I hope I was able to show that thinking on what we can slice and what we can lump can generate new ideas. Tort law offers a very lumpy protection, consisting of the full scope of the victim’s harms. If one is found to have been negligent, committed trespass, or made a libelous statement, tort law would force her to bear the full scope of her victim’s damages. Such a protection is not objectionable, perhaps, when the entitlement is a classic property right; but it runs into unanticipated problems when there are third party effects. In particular, in defamation law, audiences draw inferences and assign credences based, in part, on the legal consequences of sharing falsehoods. Using a lumpy tort-approach makes certain statements appear more credible than they should be, and others less so. Facilitating the use of truth bounties is a method of slicing this lumpy tort liability and allowing media outlets to more effectively communicate with their audience, while limiting the harmful effect of speculative stories. Fennell’s conceptual framework directs attention to such basic architectural choices we make in the law. “Because a linear relationship between inputs and outcomes is often simply assumed without comment in economic analysis, developing a mental habit of asking ‘what if the effects are nonlinear?’ can often transform the conversation.” At the very least, truth bounties are an exercise in implementing this powerful mental habit.