The Organization Judge

One of the most alternately celebrated and criticized accomplishments of the Trump administration has been its appellate judicial appointees. In this Essay, I show how President Donald Trump’s appointees follow from, and yet also differ from, the template created by Ronald Reagan, and followed by every president, Democrat or Republican, since. When it comes to credentials, prosecutorial experience, and time spent in legal academia, Trump’s appointees are like those in prior administrations. But they are younger, have spent more time in politics, clerked, are less likely to be sourced from other federal courts, and have spent less time in private practice. I argue that these changes are likely to lead to a less predictable appellate judiciary, and suggest that appointers interested in stable doctrine should choose appellate judges with more private-practice, and less political, experience.

In the 1950s, American corporate executives were overwhelmingly white, male, and valued progression within well-defined hierarchies over creativity. William Whyte dubbed the type the “organization man,” in one of the more famous works of popular management studies of the era.1 In 2001, David Brooks riffed on Whyte’s paradigm with a study of the “organization kid,” a smart, polite, and somewhat docile pursuer of the perfect resume. These kids did not rebel; rather, they complied with the goals their parents had set for them, attaining technical excellence but exhibiting a worrying lack of independence. To Brooks, “they are the logical extreme of America’s increasingly efficient and demanding sorting-out process, which uses a complex set of incentives and conditions to channel and shape and rank.”

The “organization person” paradigm can be applied beyond the bounds of corporate America or higher education.2 The process of acculturating candidates to a rigorous and institutionalized selection and promotion process that prizes conformity and the adoption of the norms of the appointers happens elsewhere. In this Essay, I argue that the paradigm applies to the selection of appellate judges.

We are living in the era—and perhaps, in the Trump administration, the apotheosis—of the organization judge. The New York Times has said that “President Trump’s imprint on the nation’s appeals courts has been swift and historic,” and on March 14, 2020, devoted over 6,200 words to the study of those appointments. Other observers, ranging from far-right to far-left, and including the president himself, have said that Trump’s transformation of the judiciary will be one of his most far-reaching accomplishments. He has appointed two Supreme Court justices, and as of this writing is trying to appoint a third.

I draw upon biographical information of each of President Trump’s appellate appointees confirmed as of January 1, 2020, collected by the Federal Judicial Center, and compare it with the biographies of appointees in the prior five administrations. The data show that, although there is plenty of continuity when it comes to the modern appellate appointments, Trump appointees clerked more often, worked in political jobs more often, and spent less time in private practice than the appellate judges picked by prior administrations.

These facts are worth considering in their own right. They paint a picture of what the judiciary looks like today, and how various resumes make it to the top of the appointers’ lists. But I also offer a normative contribution in this Essay: I argue that this trend is not a good thing, and moreover, there is a simple way that should appeal to pro-business conservatives, and perhaps also to moderates of both parties, to fix it all; we should appoint more judges with more private-practice experience.

The organization-judge era began with Ronald Reagan’s presidential administration, which, of the last six presidents, is the administration with the most similar record of appointments to the Trump administration. President Reagan picked appellate judges with sterling resumes and a known track record designed to ensure ideological predictability. His successors have followed his approach, meaning that one of the themes of judicial appointment strategies regardless of the occupant of the Oval Office has been stability.3 One hundred eighty-six of the appointees between 1980 and 2020 graduated from the same twelve law schools. Twenty-two percent served as federal prosecutors before joining the appellate bench. Twenty-six percent were promoted from state courts. Thirty-six percent had some relationship with academia, serving as a professor or an adjunct before appointment, Thirty-two percent were promoted from another federal court.4 And almost none of the appointees between 1980 and 2020 had substantial experience in a non-law business, elected politics, criminal defense, or working for public interest organizations of either the right or the left.5 These backgrounds applied regardless of the political valence of the administration in question. In sum, appellate judges are of a type, and that type has a reasonably predictable resume.6

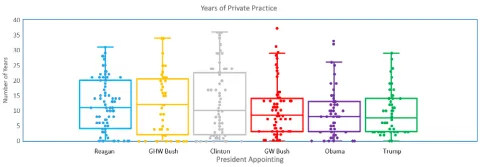

Nonetheless, the Trump administration’s preferences for appellate appointments offers some differences—or, perhaps, some particularly pointed continuations of existing trends. Appellate judges have been increasingly likely to serve as law clerks upon graduating from law school, but only four of Trump’s appellate appointees failed to clerk—far fewer non-clerks than any other administration. Moreover, his appellate picks almost always clerked for conservative judges, and more than a third clerked on the Supreme Court, more than any other administration. After that, Trump’s appellate appointees’ legal careers have been more likely to contain stints in the ivory tower, political appointments in state governments, political jobs in the federal government, or all three of these, than to have the careers of judicial appointees in prior administrations. Fewer of Trump’s appellate appointees were promoted from lower federal courts. Trump’s appellate judges also spent less time in private practice, with thirteen of his appointments having spent five years or less working for a law firm. The mean years of private practice over the average Trump appointee is less than that of any of the prior five administrations, averaging 9.34 years of private practice, while Obama nominees averaged 9.73 years, G.W. Bush nominees 10.5, with the three administrations preceding Bush’s all averaging 11.8 years or more.

The decline of private-practice experience as a prerequisite for appointment animates one of the chief concerns of this Essay. The amount of time that judges of any stripe spend in private practice is decreasing. On average, the hundred-odd justices appointed to the Supreme Court each spent almost seventeen years in private practice before joining the Court.7 Trump’s appellate appointees have done so for slightly more than nine. Trump’s judicial appointees, in other words, increasingly have a bureaucratic, political, or academic background. And often, they have all three. As judicial nominations have become politicized, nominators have dispensed with graybeards and looked to ideologically committed youth to fill appellate vacancies.

To illustrate the point, consider how the career of one of Trump’s most recent appointees, Steven Menashi, compares to one of Reagan’s final appointees, David Ebel. After graduating from Stanford Law School, Menashi clerked for Judge Douglas Ginsburg on the D.C. Circuit and then for Justice Samuel Alito on the Supreme Court, after which he became an Olin-Searle fellow at Georgetown University Law Center. Starting in 2011, he worked at Kirkland & Ellis for six years; he was also a Koch-Searle Research Fellow at the New York University School of Law between 2013 and 2015. In 2016, he left to become an assistant professor of law at George Mason University. There, and before, he took some controversial positions. As the New York Times put it, Menashi “had a trail of inflammatory writings about feminism and multiculturalism.” He joined the U.S. Department of Education in 2017 as Acting General Counsel, an extremely high-ranking position for a young lawyer. And then, in 2018, Menashi was picked to be a special assistant and associate counsel to President Trump. After being nominated to the Second Circuit, and despite being opposed by both of the senators in his home state, “[h]e . . . declined to answer specific questions about his role in the Trump administration on family detentions and education policy.” He was confirmed at the end of 2019, on a closely contested Senate vote.

In contrast, consider one of Reagan’s last appointments, David Ebel. Ebel clerked for Associate Justice Byron White, but that Supreme Court clerkship is about all that his career had in common with Menashi’s. Ebel then joined a law firm, Davis Graham & Stubbs, and stayed there for twenty-two years, including a two-year stint as an adjunct at the University of Denver’s law school. He was confirmed in 1987 by unanimous consent, serving until 2006, when he was succeeded by Judge, now Justice, Neil Gorsuch. Ebel, it turned out, was a moderate judge; time will tell what sort of a judge Menashi will be.8

We will see whether the new resumes lead to a different kind of judicial outcome, but the intuition here is that these judges are more likely to be ideologically committed than were judges with less political and more private-practice experience. Their background may encourage a degree of ideological conformity that is harder to pull off when working as an associate and then a partner at a firm that serves all sorts of clients. Trump’s appointees may also have a different and less cautious view about the costs of significant judicial interventions and the benefits of incremental conservativism. They do not have to adapt their views to fit those of their clients, and their clients, if any, are not diverse: they are conservative politicians and policy advocates, not corporations who can range from technologic visionaries to customer-sensitive consumer-product manufacturers, to smokestack and labor-union–burdened industrialists.

In short, the resumes of the new federal appellate judiciary looks less cautious Burkean conservative and more organization-judge conservative, and the organization looks a lot like the Republican Party—the party itself, as opposed to its supporters.9 Burkeans are suspicious of radical change, and are named after the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher Edmund Burke who was cautious of change partly because the stakes of change, particularly of changing governance, were high and were therefore not to be undertaken lightly.10 Burke believed that “good order is the foundation of all good things,” and that sudden changes to that order was likely to be negative.11 When applied to judicial decision-making, Burkean ideals “conjoin a reverence for tradition with the embrace of constraining ideals of judicial role and craft,” as Richard Fallon has put it.

One form of judicial decision-making that has been in vogue is judicial minimalism, or “the phenomenon of saying no more than necessary to justify an outcome, and leaving as much as possible undecided.” The idea was that judges would decide cases as narrowly as possible, leaving as much as possible undisturbed, and “would offer rationales that could command assent from a broad spectrum of public opinion.” Minimalists, I argue, are Burkean conservatives—which a conservative administration ought to like—and are unlikely to come from the background of the current organization judge.

With this analysis comes a prescription, one that might not appeal to the current president and those who advise him on judicial appointments, but one that might appeal to the business community, to moderates in the Senate, and thereby to a different balance of power in a right-of-center administration. Left-of-center administrations might also prefer Burkean judges with more liberal values. Liberals, of course, might want to recreate the process that the Trump administration has adopted, only with leftist appointees. My recommendation is unlikely to move them.

The president should seek—and senators should demand—to appoint more lawyers to the appellate judiciary with a legal practice background. And if the president and the Senate are inclined to appoint business-friendly cautious conservatives, they should choose more law-firm partners. As I have suggested, Democratic presidents may be better served by the same policy, at least if they want liberal but cautious lawyers. Finally, moderates of both parties may find such appointees more congenial.

In other words, this Essay takes precisely the opposite view of the activist co-founders of Demand Justice, Brian Fallon and Christopher Kang, who have asserted, incorrectly, at least when it comes to the all-important appellate appointments, that “corporate-law partners came to dominate the pool of judicial-nomination candidates” for both parties, and have argued misguidedly that “we don’t need any more corporate lawyers on the federal bench.” Most Americans work for corporations; it is not unreasonable to hope that the lawyers who staff the judiciary understand the context in which they pursue their careers and advance their interests.

In what follows, I review the literature on appellate appointments, and then look at the careers of appointees by the Trump administration, and compare them to prior administrations. I then argue for the advantages of more private practice experience in these appointees, and consider some potential objections to my case.

I. The Organization Context

A. The Mighty Appeals Court

The composition of the appellate judiciary is worth studying because judges are powerful officials in their own right. The power they wield has unsurprisingly led to the production of an academic literature on appellate judges, evaluating them on the basis of their quality, their demographic characteristics, and their ideology, but not often enough on their pre-appointment careers.

Appellate judges sit on three-judge panels and hear every sort of federal appeal, meaning that they have a say in how many of the most important federal laws will be interpreted. Moreover, the number of appealed federal cases is large: the twelve regional federal courts heard 27,926 appeals in 2018. By comparison, the number of cases heard by the Supreme Court is small; in 2018, the Court granted certiorari to 78 petitions for review. The implication is straightforward: court-of-appeals judges receive, as a first approximation, almost no supervision from the Supreme Court.12 They are, in the vast majority of cases, the end of the line for litigants, making the appellate courts, to twist Justice Robert Jackson’s description of the Supreme Court, infallible because they are almost always final.

Federal judges can hold their positions for far longer than any other appointees in the federal government, meaning that these powerful officials serve lengthy terms—really how long they hold their positions is up to their taste and their health regimens, along with their willingness to accept a low-paying, if high prestige, legal job. Once in place, appellate judges are almost impossible to remove. Only fifteen judges have been impeached between 1789 and 2010, and only nine of those were convicted by the Senate.13 The Constitution affords judges lifetime tenure and guarantees them no diminution in salary while in office, and judges’ salaries are among the highest in the federal government.14

Finally, the job offers the tantalizing prospect of an even more influential promotion. These days, the circuit courts nearly always provide the pool of candidates that presidents use to make appointments to the Supreme Court.15 Of the nine current Supreme Court justices, eight first served as federal appellate judges, and the one who did not, Elena Kagan, was nominated to become one, although she was never confirmed.16

While district court judges can obtain their positions through networks that go through their home state senator, appellate appointments have long been controlled by the White House.17 Presidents increasingly want to be sure what they are getting when they are getting an appellate judge, and so they put them, as Jack Knight, Andrew Martin and Lee Epstein have explained, through “extensive screening.”

Given the importance of the federal appellate judge, scholars have tried to create reliable measures of appointee quality, which, if adopted, would add to the extensive screening would-be judges already face. Stephen Choi and G. Mitu Gulati, for example, came up with an approach to evaluate judges based on their citations, productivity, and willingness to write separately from their colleagues. Frank Cross and Stefanie Lundquist proposed their own way of assessing appellate quality, while other scholars ranging from Richard Posner to Larry Lessig have tried to figure out which judges are the most influential, again, through empirical methods, almost always involving citation analysis. Other scholars have evaluated judges on more qualitative grounds.18 That this literature has attracted prominent scholars from across the ideological spectrum is a testament to the importance of appellate judges.

But quality is not the only relevant factor, of course. Federal judges can be evaluated on several different metrics, including age, diversity, and ideology. Many have observed that federal appointees are younger than they used to be, raising the specter of a thirty- or forty-year term for a federal officer, a term that far exceeds the ordinary length of even the longest appointments to agency positions, and one that raises the question as to whether these judges will stay in their positions until retirement, given the riches of the private sector and their relatively brief time in that sector before appointment.19

Others have complained about the ideology of appellate judges these days, a concern I share. Most conservative appointees are associated with the Federalist Society, a group organized to foster conservative legal thought. As the New York Times observed in March, all but eight of Trump’s appellate appointees have been connected with the organization. Membership may serve as a signal of ideological bona fides, although it is difficult to see how membership alone (which is cheap talk) would guarantee some sort of true faith. It is possible that society participation could serve as an extended proving ground designed to separate conservatives from faux-conservatives, and talent from the less talented. For its part, the American Constitution Society purports to play a similar role for liberal lawyers, though few think it has achieved a similar sort of centrality.

While few would argue that organizations designed to develop thinking are beyond the pale, some worry that organizations designed to foster a particular ideological perspective on the law are unlikely to produce even-handed adjudicators. This concern led the Committee on Codes of Conduct of the Judicial Conference of the United States to issue, then retract, a draft advisory opinion in January 2020, concluding that “formal affiliation with the . . . Federalist Society, whether as a member or in a leadership role, is inconsistent with” five canons of the judicial code.20 Still others have observed that the Trump administration has appointed less racially diverse judges than prior administrations and more males than, at least, the Obama administration.21

Ideology, age, and diversity are critical, of course, but this Essay focuses on another difference between the judicial appointments of today and those of the past: their pre-appointment careers. In this, I am in good company. Lee Epstein and Jack Knight long ago observed that Supreme Court justices were increasingly unlikely to serve in private practice. As Epstein and Knight put it, modern justices “lack[ ] experience . . . in the private practice of law that was so characteristic of those appointed before.”22

B. Politicians in Robes?

Some wonder whether it makes sense to study judicial quality. They assume that appellate judges simply vote their ideological preferences rather than reaching objective conclusions about the legal merits of a case. Judges could simply be “politicians in robes.” They are appointed by politicians, who might want to put partisans aligned with their policy preferences in important positions. As Brian Feinstein has observed, “[t]he adage ‘personnel is policy’ is a chestnut that has been used in Washington to describe the importance for a new president to appoint political loyalists.”

The appointments process, and the interest of partisans in it, has changed over time from something that was rather non-partisan to something much more politicized. When the organization-judge era began is not clear, although this Essay places its beginning with the Reagan administration. Over the time of its existence, however, it has become procedurally easier to get nominees confirmed.

Partisan vetting of judicial appointments certainly was not in play in the 1950s, when the moderately conservative president Dwight Eisenhower ascribed his two greatest mistakes in office to his Supreme Court appointees Earl Warren and William Brennan, two lifelong Republicans who turned out to be very liberal lions of the bench.

It may not have been in play to the extent it is today even more recently than the 1950s. In 1991, Einer Elhauge argued that “we do not in fact observe extensive interest group influence over judicial appointments, at least not by interest groups with an economic agenda.” Elhauge thought that, putting aside social questions like abortion and civil rights, the judiciary was less ideological on other questions with hot-button implications in Washington for lobbyists and insiders, such as competition law or corporate free speech, but less salience in the popular imagination.

But times have changed—and they had probably already changed by 1991. Today, judicial confirmations are frequently party-line votes, while in prior administrations, the Senate was much more likely to consent to presidential nominations, as evidenced by the unanimous vote to confirm Judge Ebel. In the 115th Congress, which sat between 2017 and 2019, only one Republican senator ever voted against a Trump nominee; the average Senate Democrat voted against over half of them.

But even as partisanship over appointments has increased, it has become much easier to get an appellate appointment through the Senate. Prior administrations were confronted by a filibuster and blue-slip process that allowed home-state senators to reject proposed appointees, particularly to the trial courts. In the Trump administration, the blue-slip process has been ignored for appellate appointments, and the filibuster has been eliminated. There is some evidence that this has affected the sort of candidate for appointment—they may be younger, more ideologically committed, and more willing to signal their commitment. Senators, in short, now have different kinds of power, and better reasons to invoke partisan interests, than they did in the 1980s. This dynamic makes the consistencies that we see in appellate appointments between 1980 and today all the more interesting.

II. The Pre-Appointment Career of the Modern Appellate Judge

In this Part, I review the ways that organization judges look similar, and the ways that they look different, across administrations, highlighting the real, if not enormous, differences between President Trump’s appellate appointees and their counterparts in other administrations.

A. Appellate Elites

The Trump administration, like Republican administrations before them, tend to value a glittering resume in an appellate judge. If American politics is defined by a party of cosmopolitan elites and the diverse working class squaring off against a party of the white working class and bourgeoisie, you wouldn’t know it from the resumes of Republican appointees. They glitter with fancy clerkships, private school educations, and relatively brief stints at large firm law jobs. The typical Republican-appointed appellate judge, in other words, is an elite, not a workaday lawyer with workaday degrees.23

Both Republicans and Democrats send their “best” to the appellate bench—if best is defined as a relatively narrow slice of Ivy League or Ivy League adjacent trained lawyers who, usually, have landed clerkships. The number of appointees since the Carter administration who went to twelve schools—Columbia, Duke, Northwestern, Texas, Stanford, Virginia, Georgetown, Chicago, Michigan, Yale and Harvard, in ascending order of placements—exceeds the number of appointees that graduated from all other law schools combined. In total, the top three providers of appellate judges are Harvard, with fifty-one appointments, Yale, with thirty-four appointments, and Michigan, with seventeen. Chicago, like Georgetown, can boast of thirteen appointments.24 The preference of Republican presidents for Chicago graduates is evocative: All but one of Chicago’s graduates were appointed to the appellate bench by Republican presidents, and eight of the total by President Trump—but then again, so were all but fifteen of Yale’s along with all but sixteen of the Harvard graduates.

Almost none of the judges appointed after Reagan has had any sort of high-level business experience. And during the Reagan administration, only a few did. One Reagan appointee had served on the executive committee of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, a leading investment bank of the time, and another had been the vice president of the Catawba Corporation, a real estate services company.

By the same token, there are very few criminal defense lawyers or public interest lawyers among the ranks of the appellate judges from either the Democrat or Republican side. The Trump administration is no different in this regard, although some of its appointees have worked for boutiques aligned with particular causes—not public interest firms, necessarily, but firms that might be picked to bring conservative impact litigation.

B. The Puzzling Persistence of Academics

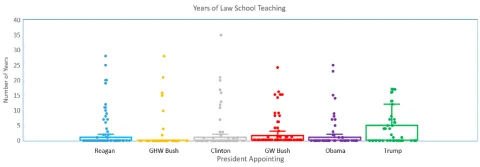

All administrations like to appoint judges with some connection to legal academia, sometimes only as adjuncts, but often enough as tenure-track professors.

The Trump administration and the Reagan administration have put the highest proportion of lawyers with academic careers on the bench.25 Thirty-one of Reagan’s eighty-three appellate appointments and twenty-three of Trump’s first fifty appointments spent some time at a law school. It is, however, fair to say that the impact these judges made as law professors, on aggregate, differed substantially. Reagan’s appointees included three titans of legal scholarship—Richard Posner, Frank Easterbrook, and Robert Bork—along with Pasco Bowman, who was the dean of Wake Forest University and the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s law schools. Posner and Easterbrook are considered among the leading figures of law and economics scholarship, with Posner sometimes mooted as a potential Nobel Prize winner for contributing so much to the development of the influential field. Posner, Easterbrook, and Bork revolutionized thinking about how and when the antitrust, corporate, and contracts laws ought to be enforced and understood.26

Trump’s appointees include only one really well-cited professor: Stephanos Bibas from Penn Law School. His other academic appointments have certainly had respected careers in academia: Neomi Rao, David Stras, Amy Coney Barrett, and Alison Eid had productive careers at good law schools; Joan Larson had a short tenure-track career but a lengthy association with Michigan Law School after her appointment to the state supreme court. But in many cases, the association with academia was passing. Eleven of Trump’s appointees served as adjuncts, some, including Daniel Bress and Kevin Newsom, at multiple schools.

Adjuncting, which could involve a variety of different ways of engaging with a law school, is, to be sure, a reason why academics comprised such a large proportion of appellate appointees across administrations. Nonetheless, many of these adjuncts had lengthy runs with the job. This would not place them in the bosom of the ivory tower but certainly represents repeated engagement with law students and some exposure to scholarly analysis.

One might wonder what is so appealing about the ivory tower, especially in an era where legal academia has begun to separate from the legal profession. While once law professors wrote treatises and restatements designed to reflect the state of the law, Judge Richard Posner presided over an era where professors were less likely to work on doctrine, and more likely to turn to social science to inform their research. There are famous studies establishing that academics have become worse at predicting how the Supreme Court might decide a case than was a computer algorithm, and both the professors and the computer were substantially worse at prediction than a group of District of Columbia lawyers.27 There is little to suggest, these days, in other words, that legal academics might be good lawyers. Yet, presidents still like to draw from their ranks when it comes to picking the most influential lawyers in the land.28

The puzzling persistence of legal academics on the appellate bench is likely attributable to three factors. First, like state appellate judges, academics must write, giving presidents a large body of work to evaluate when considering whether to make an appointment. Not every academic produces as large a trove of material as Judges Posner and Easterbrook, but the on-the-record requirement may help professors survive due diligence in the way that a law-firm partner, who speaks on behalf of others, rather than herself, would not. Second, path dependence is surely relevant: presidents appoint law professors to the bench because, ever since Reagan, that has been a thing that presidents have done, perhaps reassuring potentially skeptical senators that the appointee’s resume is not an outlier, but rather part of an appellate appointment tradition. Finally, as this Essay has argued, academics are advocates for the ways they understand the world, and, as I have suggested, presidents might want those people, particularly if they want a world where judges push their ideological commitments fiercely. Choosing a career in the field is a costly signal, moreover, of a commitment to those ideas; money is being left on the table to pursue them in the less well-paid precincts of the academy.

C. Tough on Crime

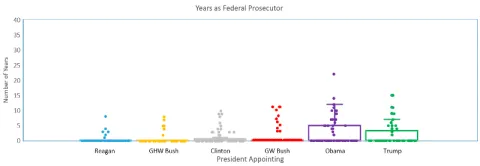

Both Democrats and Republicans agree that former federal prosecutors are well-suited to become appellate judges. Fifteen of Trump’s first fifty appointments spent some time in the U.S. attorney’s office, usually as an assistant U.S. attorney, rather than the U.S. attorney—or head of the office—herself. The numbers essentially match those of all presidents since Reagan and the first Bush administration. While Reagan and Bush were only willing to appoint thirteen prosecutors to the appellate bench between them, the other administrations all essentially doubled that total.

What is different about Trump’s appointees is that their prosecutorial experience essentially ticked a box, instead of representing a career. The median years of service for Trump’s appointees who were prosecutors was three years. For Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, it was eight and nine years respectively. Those prosecutors were all but criminal-law lifers, at least given the decreasing time that appellate judges have to practice before their appointment. Trump’s appointees look more like organization judges adding to their curriculum vita.

It is possible to look at appointees from the U.S. attorney’s office and see cautious bureaucrats, rather than activist judges of the right or left. Prosecutors are, after all, civil servants. But scholars have increasingly worried that modern federal prosecutors lack caution, or indeed any check on their discretion. As Rachel Barkow has explained, “In most cases . . . , the prosecutor becomes the adjudicator—making the relevant factual findings, applying the law to the facts, and selecting the sentence or at least the sentencing range.” The result is that “there are currently no effective legal checks in place to police the manner in which prosecutors exercise their discretion to bring charges, to negotiate pleas, or to set their office policies.” Rick Bierschbach and (now Judge) Stephanos Bibas have also complained that “prosecutors exercise virtually unreviewable discretion in deciding which charges to file, which deals to strike, and which sentences to recommend.”

These critics paint federal criminal law as something governed by plea bargains and prosecutors who hold most of the cards in the negotiations over the content of those pleas. A president in search of activist judges might welcome a group of unconstrained inquisitors to the bench, although the willingness of administrations to tolerate appointees raised in this culture of discretion has crossed aisles and reached back as far as the Clinton era.

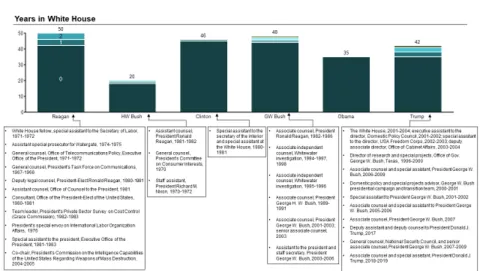

D. Politicians Who Win Robes

President Trump’s appointees have more political experience than do the appointees of prior administrations, with the possible exception of Reagan’s. But that political experience is of a particular kind. Rather than winning elections, these appointees served as counselors to elected officials or heads of departments. President Trump has appointed more officials with political experience at the Department of Justice, more officials with political experience at the White House, and held serve when it came to appointments with experience at the politically sensitive DOJ offices like the Office of the Solicitor General or the Office of Legal Counsel. When it comes to political experience and other federal departments, the Trump administration has outdone both the Obama and the second Bush administrations.

More than any other indicator, this indicator suggests that the president values political experience in his appellate appointees. With eight appointees with DOJ political experience, five in policymaking roles at the Office of Legal Counsel, one from the Solicitor General’s office, seven with White House experience, and six with political experience in other departments, over half of President Trump’s initial appellate appointees have served in a political position in the executive branch. The numbers are small but evocative; one assumes that this sort of background would be conducive to acting as a political operative, or at the very least, inclined to afford the executive branch wide latitude when it comes to judicial review.

Whatever the case, this sort of experience, especially when paired with the appointees selected from political positions in state government, marks the Trump judicial appointees as, although resume-consistent with those of other administrations, different in career before appointment. On background alone, it raises the specter of judges as politicians in robes.29

But if the numbers speak for themselves, one need not assume the most political scenario. There could be a supply-side story. Perhaps appointable candidates on the Republican side serve in political positions because the Republican bench is short, with credentialed conservative lawyers in high demand and small supply. Perhaps the Republican Party or Federalist Society encourages political participation without inculcating some form of executive or conservative activism in those who take up the mantle to serve.

Although, in my view, the story is relatively telling, it is worth noting that executive branch political service is not a requirement for appointment. But the number of Trump appointees who have held political or politically sensitive appointments is high. In this respect, the Trump administration looks most like the Reagan administration. Both administrations appointed a number of judges with DOJ political experience. The Reagan administration appointed eight appellate judges with White House experience; the Trump administration has appointed seven as of 2020. To put it differently, both Reagan and Trump picked more White House experience than the four administrations between them combined, as the below figure shows.30

E. The Rise of the (State) Solicitor General’s Office

If the number of political appointments in the executive branch suggests that the current administration’s judicial appointees are encouraged to have a political role, the rise of experience in the solicitor general’s office requires some more parsing. These offices are relatively new, and reflect the increasingly prominent participation in litigation against the federal government that state attorneys general have made part of their remit.31

It used to be the case that appeals were handed off to experienced, and sometimes sleepy portions of the state attorney general’s office. But most states have now created professionalized solicitor generals who decide what cases to take to federal court and, in some cases, how to handle appeals in state courts.32 These offices are often quite small, and offer their incumbents the prospect of a Supreme Court argument, perhaps over a death penalty case or a section 1983 action against a police officer or prison warden. They have been filled with ambitious lawyers of both the right and the left stripe, depending on the political valence of the state.

The Trump administration has broken new ground in appointing attorneys with state solicitor general experience to the federal courts. It has promoted seven appointees with a solicitor general background, more than all of the other prior administrations combined. One of its appointees served in no less than three western-state solicitor general’s offices: Lawrence VanDyke.33 Three appointees served in the Texas solicitor general’s office: James Ho, Stuart Duncan, and Andrew Oldham. Britt Grant served as the solicitor general of the state of Georgia, Eric Murphy did so in Ohio, Allison Eid did so in Colorado, and Kevin Newsom did so in Alabama. The only other administration that promoted state solicitor generals to the federal bench were the second Bush administration, which appointed Jeffrey Sutton of Ohio to the Sixth Circuit, and Timothy Timkovitch of Colorado to the Tenth Circuit.

All of these appointees obviously, by dint of their SG positions, have experience in appellate advocacy, and in that sense are particularly qualified to serve as appellate judges. But here too, the turn to political positions, and away from private practice is instructive. These positions blood young, politically minded attorneys in relatively high-stakes appellate arguments.34 Moreover, the solicitors general generally choose the cases they wish to handle in person, and which cases are meant to be appealed. In recent years, they have served as the courthouse lawyers for politicized state challenges to federal policies.35 Once again, these officials do not serve as advocates for clients with a broad array of interests and needs, but rather report to an elected attorney general.

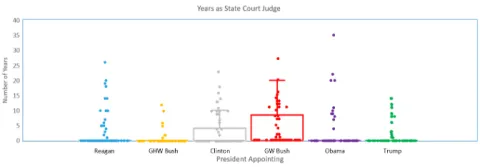

F. The Steady Promotion of State Court Talent

Another fecund source of candidates for appellate appointment that crosses all administrations are state court judges who have demonstrated the capability for a step up, or at least a lateral step, to the federal judiciary.36 Ten Trump appointees have had state-court experience, a number broadly consistent with that of most administrations after George H.W. Bush. Bush the younger promoted by far the most state judges to the federal bench, but an affection for state court judges has been bipartisan. State judges would seem less likely to be politicized, given the often uncontroversial verities of state court litigation. But state courts are certainly places where a conservative judge can demonstrate that they are tough on crime, receptive to the death penalty, and hostile to plaintiffs’ lawyers.37

More often, state courts are sources of diversification for the federal judiciary. They are the places where female appointees can be found, and sometimes minority appointees as well. Five of President Trump’s ten appointees with state court experience are female, and one, Barbara Lagoa, is Hispanic. I view them as a stable source of federal appointments that all administrations share. And during the Trump administration, state courts have promoted more judges to the federal appellate bench than have the federal district courts.

G. The Disappearing Trial Court Promotion

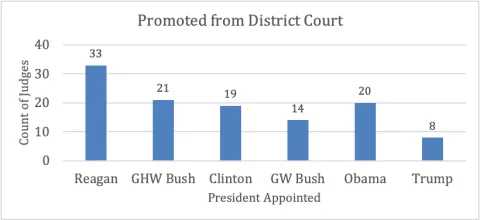

The final important source of appellate talent come from the ranks of the district courts and magistrate judges, but the Trump administration has brought far fewer of these to the appellate bench than did the Reagan administration, the president whose appointing practice Trump otherwise most resembles. Thirty-three of the eighty-three appellate judges Reagan appointed—almost 40 percent—had trial court experience. Eight of Trump’s fifty appointees up to January 1, 2020, or 16 percent, had that sort of experience. It is not that these judges are also-rans in the administration’s thinking—one of them, Amul Thapar, before being promoted to the Sixth Circuit, was placed on the short list of judges who might be promoted to the Supreme Court. But it is the case that appellate appointments, for Trump, are more likely to come from elsewhere.

District court judges, of course, have the sort of track record shared by academics, and perhaps welcomed by appointers interested in establishing what sort of appeals the candidate might find to be convivial. But it is also the case that state courts now attract reasonably talented and well-credentialed appointees now, especially at the high court level, where partisans of various ideological stripes have taken interest in the judicial officeholders, and can serve as an alternative sources of judges with pre-existing track records. Certainly the Trump administration has, like its predecessors, looked to the state courts to meet federal appellate appointment needs.

For whatever reason the current administration has preferred to look for its candidates from other sources—it is the only administration with a single-digit record. The elder Bush promoted over half of his few federal appellate appointments from the lower courts—twenty-one of his forty-one. President Clinton promoted nineteen, and President Obama twenty-one as well. Only the younger Bush evinced anything like President Trump’s preference for alternative sources of appellate talent. Bush promoted fourteen federal judges, comprising 22 percent of his total number of appellate appointees.

H. The End of Military Service

There is one other, somewhat less surprising, change in the careers of appointees to the federal appellate judiciary. As service in the military has declined overall, and as the draft has abated, so has service in the military declined on the resumes of the current administration’s nominees. President Reagan in particular but also both President Bushes were more likely to nominate judges with military experience. None of President Trump’s nominees have military experience, and so did only three of President Obama’s. Reagan’s fifty appointees had a combined 158 years of military experience among them. If anything, the disappearance of military service is one difference between appellate judges and elected politicians, where both parties value prior military service.

The end of military service backgrounds means the end of another culture that does not particularly distinguish between liberal and conservative, but rather, that is designed to give every member of the military a similar perspective, with similar goals and values.

III. The Problems of the Organization Judge

Judicial appointments are one of the principal accomplishments and priorities of Trump’s presidency. He often brings it up in rallies, and tells his audience that it will be one of the keys to his reelection. It has certainly been a priority of his Senate: While many executive appointments remain unfilled, judgeships have been filled as quickly as they have opened. In the first three years of his term, President Trump has appointed one-quarter of the entire appellate judiciary, selecting more judges than either Presidents Obama or Clinton managed in their eight years in office. “We are shattering every record!” the president has tweeted about his judges.

But Trump’s appointments look more political and less experienced in private practice than the appointees from other administrations, which also have trended this way. If the goal is to create a predictable and small-c conservative legal system, with moderate decisionmakers who understand the concerns of the businesses they used to represent, less private practice and more political experience will not work. Many Republicans, to say nothing of median voters, the Chamber of Commerce, and Democrats of all stripes, would find that sort of judiciary more amenable than a less predictable, and more conservative, one. A moderate judiciary is good electoral politics as well as good policy.

The increasing politicization of judges has been a feature of every appellate appointee since the Reagan administration. From what we see from the biographies, lawyers who hope to obtain appellate appointments know that they will be best served with some time in the government, and ideally in academia as well, particularly if they are conservative. Private-sector careers are getting shorter and shorter at the same time.

But it is by no means clear that judges who spent very little time in the private sector are the right choice for a predictable and cautious “least dangerous branch.”38 Instead, private-sector experience might be particularly appealing for an administration that would like to see a judiciary amenable to business and cautious in temperament.39

The differences between two Supreme Court justices who were in the scope of this Essay during their tenures on the D.C. Circuit, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Clarence Thomas, illustrate the main inference drawn in this Essay. Roberts certainly spent time in the government—he spent six years in political or appellate-advocacy positions—but also spent twelve years in private practice. He is often characterized to be the most cautious and incremental of the conservative justices.

Justice Thomas, on the other hand, spent eight years as a political appointee chairing the EEOC, three years working for state government in Missouri, two years working for a Republican senator, two years working as a political appointee in the Department of Education, and two years working in business, for the chemical company Monsanto. His background, in sum, is mostly in political jobs, rather than in private practice.

Thomas, were his opinions to become the majority, would radically transform American governance. He recently has called for the most cited case in administrative law to be overruled, along with, this year, another case affirming it, National Cable & Telecommunications Association v. Brand X Internet Service. For what it is worth, he wrote Brand X. Nonetheless, he concluded, the decision, “has taken this Court to the precipice of administrative absolutism” and was “inconsistent with accepted principles of statutory interpretation from the first century of the Republic.” A Thomas-led Court, in sum, would be willing to overrule old decisions, even recently handed down decisions that Thomas himself wrote or supported.

My claim essentially comes down to the idea that corporate law partners are more likely to be moderate, small-c conservative judges, and less likely to be politicized activists. Judges who spent time as law professors and state solicitor generals have spent their career before appointment selecting ideological positions, and spending their time making the case for them. They are not—or at least not as much—constrained by their clients’ preferences or by the limited resources of a law firm.

In my view, having more ideological judges is a negative development. These appointees did not have to get along with ideologically different lawyers who work at their firms, certainly not at the partner level. They are also more likely to have spent their time pushing conservative policies on behalf of conservative politicians. Or, they spent time in academia, picking the issues on which they would like to work. These jobs required less consensus and moderation then would a business operation comprised of ideologically diverse individuals serving clients with a variety of different needs, who need to get along to prosper in a competitive market.

Nor is it only about ideology. In a country where the vast majority of lawyers are in private practice, the new class of appellate judges do not look much like their profession.40 Even the Center of American Progress, a liberal think tank, acknowledges that “[o]ver the course of a legal career, a lawyer learns about statutes, guidance, legal philosophy, and precedent grounded in the perspective of advocating for that client.” But the modal American client is not a state or federal government agency; it is an organization located in the private sector. Nor is it the case that the federal judiciary benefits from government experience because federal cases are likely to be administrative; instead, criminal and prisoner matters dominate the federal docket.41

Moreover, private-practice lawyers are likely to be more cautious, and therefore more minimalist than lawyers with more political jobs on their CVs. They by definition may have spent less of their time as political advocates, and the advocacy in which they will have engaged will be advocacy on behalf of someone else, a feature that gives them experience in understanding other points of view and different perspectives. Cass Sunstein has suggested that putting ideologically different people together in the same decisionmaking body leads to more moderate decisions, and this sort of culture is likely to be particularly prominent in private firms.

In short, it is in private practice where the Burkean conservatives are more likely to be found, rather than in lawyers with White House and Capitol Hill experience. To the extent that minimalist, stable, and cautious judging is the sort of judging we should want, it is more likely to be found with lawyers who have had to put up with clients who can fire them, who have different perspectives, and who, like most Americans, are engaged in commerce.

If private practice is so good for Republicans, what about for Democrats? In my view, a similar calculus may well apply, although I will not make the full case for it in this brief Essay. Democratic politics today features a number of increasingly fervent activists who seem somewhat out of step with even their own party. For example, Elizabeth Warren, known to be hostile to the appointment of firm lawyers to political positions in the Obama Administration won many followers but very few voters in the most recent Democratic presidential campaign. If most Democrats—and perhaps also the median voter—wish for moderation, minimalist judges with private-practice experience might just be the winning policy maneuver.

I conclude by considering three objections to my proposal.

First, rather than preferring private practice, perhaps we ought to have federal judges come from all sorts of backgrounds. The Center for American Progress makes this argument. But the problem with balancing lawyers from the private sector with those from criminal-defense bar, the ranks of prosecutors, and an array of regulatory lawyers, is that private bar is so much larger than all of those other subfields. If the contribution of the various parts of the legal system were made proportionate to the number of lawyers in the profession, I would have no objection to aspiring to such a distribution among appellate appointees, because then the modal appointee would have the caution of a private-sector lawyer.

Next, one might wonder whether political experience might be a feature, rather than a bug when it comes to judicial appointments. Adjudication, after all, is a form of governance. Perhaps experience in situations where the lawyers report to politicians who have to stand for elections and respond to constituents would help judges make better governance decisions. This objection is not illogical, but it runs in the face of a long literature praising apolitical adjudication. The idea that judges are just “politicians in robes” is, while embraced by particularly nihilistic realists, thought to be an indictment of the judiciary rather than the goal. There is a case to be made that judges should be above politics; many federal judges do not vote for this reason. Emphasizing the importance of political experience is inconsistent with this longstanding priority.

Somewhat related to the value of political experience is the notion that “elections have consequences.” Shouldn’t Republicans who have the power to compose the judiciary as they see fit seek to put the most conservative possible jurists on the courts of appeals? If so, they might establish those bona fides by looking to association in the appropriate ideological society, political experience, and active participation in the relevant ideological network. It is certainly true that appointers have the power to push for the most conservative judges possible, but the point of this Essay has been that their interests, and more generally the interests of the people who elected them, will be served better by more stable and moderate adjudication. This kind of adjudication is more likely to be found in candidates with more private sector experience than the candidates who are currently being nominated for appellate judgeships.

- 1William H. Whyte, The Organization Man (1956).

- 2See, e.g., Najma Dayib, Penn Student Project Deconstructs The Myth Of Getting ‘The Perfect Internship’, The Daily Pennsylvanian (Nov. 6, 2018) (describing efforts by a student organization to normalize non-finance and non-technology internships for undergraduates).

- 3In this regard, cf. Terri L. Peretti, Where Have All the Politicians Gone? Recruiting for the Modern Supreme Court, 91 Judicature 112 (2007) (noting a “striking occupational homogeneity” in the backgrounds of judicial appointments). See also Matthew Fuhrmann, When Do Leaders Free‐Ride? Business Experience and Contributions to Collective Defense, Am. J. Pol. Sci. (forthcoming 2020) (“[L]eaders with business experience are more likely than other heads of government to act as self‐interested utility maximizers”).

- 4See Part III for a deeper analysis of these judges’ pre-appointment careers.

- 5Of course, this has led to some concerns. See, e.g., Emily Hughes, Investigating Gideon’s Legacy in the U.S. Courts of Appeals, 122 Yale L.J. 2376, 2381 (2013) (“almost all federal appellate judges share one thing in common: before they became federal appellate judges, they were not public defenders”).

- 6The claim bolstered by the fact that appellate judges, when separated into groups based on the president who appointed them, do not demonstrate many statistically significant differences on the basis of their prior experience, at least, if using a one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), which measures differences between groups, and is the appropriate test for groups with a variety of different characteristics with one intervention (in this case, appointing president).

- 7For more on the backgrounds of Supreme Court justices, see Benjamin Barton, Our Cloistered, Elite Supreme Court (forthcoming 2021).

- 8Many scholars have attempted to measure the ideology of judicial appointees empirically, though these efforts typically focus on the ideology of the Supreme Court. See, e.g., Adam Bonica, Adam S. Chilton, Jacob Goldin, Kyle Rozema & Maya Sen, Measuring Judicial Ideology Using Law Clerk Hiring (Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics No. 767, 2016); Corey Rayburn Yung, Judged by the Company You Keep: An Empirical Study of the Ideologies of Judges on the United States Courts of Appeals,51 B.C. L. Rev. 1133, 1137 (2010) (“introducing a new technique for measuring the ideology of judges based upon judicial behavior in the U.S. courts of appeals” based on disagreements with each other or with the district court judge’s decision under review). David Nixon has explored using the number of appellate judges appointed after winning election to Congress has a potential measure as well. See David C. Nixon, Political Ideology Measurement Project, Appendix A, Ideology Scores for Judicial Appointees.

- 9The reference is to Edmund Burke, the eighteenth-century Irish philosopher. For a discussion of Burkean views as applied to jurisprudence, see. Richard H. Fallon, Jr., The “Conservative” Paths of the Rehnquist Court’s Federalism Decisions, 69 U. Chi. L. Rev. 509, 449 (2002).

- 10Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) (“Society is indeed a contract. Subordinate contracts for objects of mere occasional interest may be dissolved at pleasure—but the state ought not to be considered as nothing better than a partnership agreement in a trade of pepper and coffee, calico or tobacco, or some other such low concern, to be taken up for a little temporary interest, and to be dissolved by the fancy of the parties. It is to be looked on with other reverence; because it is not a partnership in things subservient only to the gross animal existence of a temporary and perishable nature.”).

- 11Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

- 12See McNollgast, Politics and the Courts: A Positive Theory of Judicial Doctrine and the Rule of Law, 68 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1631, 1647 (1995) (a trio of political scientists arguing that “a secular growth in caseload in the lower courts will cause a loss of doctrinal influence by the Supreme Court” and empower appellate judges).

- 13See William J. Rich, 3 Modern Constitutional Law § 39:6 (3rd ed.).

- 14U.S. Const. art. III, § 1 (“The Judges . . . shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour. . . .”).

- 15Monique Renée Fournet & Lawrence Baum, Evolution of Judicial Careers in the Federal Courts, 1789–2008, 93 Judicature 62, 63 (2009) (noting “the strong tendency to recruit Supreme Court nominees from the ranks of sitting federal judges”).

- 16The exception is Justice Kagan, who was confirmed while serving as the solicitor general of the Department of Justice, as her Federal Judicial Center biography shows. Kagan, although not confirmed, had been nominated to serve in the D.C. Circuit at the end of Bill Clinton’s presidency.

- 17For example, during the Clinton administration, “the White House exerted greater control over the selection of appellate judges, while home-state senators who shared the president’s party recommended candidates who served as presumptive nominees for district court vacancies,” as one White House official explained. Sarah Wilson, Appellate Judicial Appointments During the Clinton Presidency: An Inside Perspective, 5 J. App. Prac. & Process 29, 30 (2003).

- 18See, e.g, Vicki C. Jackson, Packages of Judicial Independence: The Selection and Tenure of Article III Judges, 95 Geo. L.J. 965, 979 (2007) (assuming that, among other things, judges should have “personal integrity; high intelligence; good professional training and experience; the capacity to think and write clearly about legal issues”).

- 19For an analysis of the age issue, see Joseph Fishkin & David E. Pozen, Asymmetric Constitutional Hardball, 118 Colum. L. Rev. 915, 982 (2018) (“Democrats have not pushed through young judges to the same extent as Republicans have.”).

- 20The report drew the same conclusion about the American Constitution Society, a liberal group set up to mimic the Federalist Society. For a critique, see The Editorial Board, Judicial Political Mischief, Wall. St. J. (Jan. 21, 2020).

- 21Stacy Hawkins has argued that “Trump’s judicial appointments reveal an increasingly evident ambition to “whitewash” America.” As another critic put it, “It is stunning to me that 2 1/2 years in, he has not nominated a single African American or a single Latinx to the appellate courts;” 70 percent of the nominees were white men. Carrie Johnson, Trump’s Impact On Federal Courts: Judicial Nominees By The Numbers, Nat’l Public Radio (Aug. 5, 2019) (quoting Kristine Lucius, executive vice president for policy at the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights). The administration has since confirmed nonwhite candidates to the federal bench. Carl Tobias has observed that “a troubling pattern that involved a striking dearth of minority nominees materialized comparatively rapidly.” For a more general consideration of the problem, see Russell K. Robinson, Justice Kennedy’s White Nationalism, 53 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1027, 1060 (2019) (“the federal judiciary remains predominantly white and male”).

- 22They are also less likely to have held high political office (as opposed to the political roles in the White House and DOJ that have been more prominently part of the Trump administration appointees). Id. See also Tracey E. George, From Judge to Justice: Social Background Theory and the Supreme Court, 86 N.C. L. Rev. 1333, 1353 (2008) (considering “the influence of career socialization processes on judicial behavior, focusing particularly on experience as a prosecutor, a public or elected official, an academic, or a judge on another court”).

- 23In their classic study of Chicago lawyers, John Heinz and Edward Laumann concluded that a “fundamental distinction” divided lawyers into “two hemispheres,” one of which “represent[ed] large organizations (corporations, labor unions, or government),” while the other “work[ed] for individuals and small businesses.” John P. Heinz & Edward O. Laumann, Chicago Lawyers: The Social Structure of the Bar 319 (1982).

- 24One could be surprised by the fact that NYU has graduated eight federal appellate judges since 1980, while Columbia has only graduated five, or that Wyoming’s law school has four appointees in the modern appellate judiciary, tied with Cornell and ahead of Berkeley. But such small margins are likely a consequence of happenstance.

- 25President Reagan’s policy was quite intentional, according to one of the lawyers who worked for him at the White House. David O. Stewart, The President’s Lawyer, ABA J., April 1986, at 58, 61 (“President Reagan has drawn heavily from law school faculties in making appellate appointments.”).

- 26“Judges Easterbrook and Posner, and former Judge Bork, advance the broad claim that traditional antitrust law has imposed serious efficiency costs on the American economy.” Peter C. Carstensen, How to Assess the Impact of Antitrust on the American Economy: Examining History or Theorizing?, 74 Iowa L. Rev. 1175 (1989).

- 27See, e.g., Theodore W. Ruger, Pauline T. Kim, Andrew D. Martin & Kevin M. Quinn, The Supreme Court Forecasting Project: Legal and Political Science Approaches to Predicting Supreme Court Decisionmaking, 104 Colum. L. Rev. 1150, 1150 (2004). The more recent effort to develop quantitative techniques to predict Supreme Court outcomes relies on machine learning and has a 70-percent accuracy rate, also higher than the academic success rate from the Ruger study. See Daniel M. Katz, Michael Bommarito & Josh Blackman, A General Approach for Predicting the Behavior of the Supreme Court of the United States, PLOS One, at 2 (April 12, 2017).

- 28The classic citation for this proposition is to Judge Harry Edwards, who argued that “many law schools—especially the so-called ‘elite’ ones—have abandoned their proper place, by emphasizing abstract theory at the expense of practical scholarship and pedagogy.”

- 29James L. Gibson, Judging the Politics of Judging: Are Politicians in Robes Inevitably Illegitimate?, in Charles Gardner Geyh, ed, What’s Law Got to Do with It? What Judges Do, Why They Do It, and What’s at Stake 281 (2011).

- 30Neither administration has been too committed to appointing women. Of the fifty appellate judges appointed during the Reagan administration, three were female. Of the fifty appointed by President Trump, only nine have been female. Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama did better. For example, nearly half of all Obama appointees were female.

- 31For a discussion of their history by, among others, Trump appointee James Ho, who served as the Solicitor General of Texas, see The Rise of Appellate Litigators and State Solicitors General, 29 Rev. Litig. 545, 635 (2010).

- 32“Many states (currently the number has reached thirty-eight) have built state solicitor general offices, modeled after the U.S. Solicitor General and typically staffed by former Supreme Court law clerks.” Allison Orr Larsen & Neal Devins, The Amicus Machine, 102 Va. L. Rev. 1901, 1917 (2016); see also Jeffrey L. Fisher, A Clinic’s Place in the Supreme Court Bar, 65 Stan. L. Rev. 137, 140 (2013) (“Many states have followed [the federal government’s] suit in recent years, establishing or enhancing existing solicitors general’s offices.”); William C. Kinder, Putting Justice Kagan’s “Hobbyhorse” Through Its Paces: An Examination of the Criminal Defense Advocacy Gap at the U.S. Supreme Court, 103 Geo. L.J. 227, 247 (2014) (discussing the rise of the state solicitor general).

- 33Assuming that Texas, along with Nevada and Montana, can be considered a western state.

- 34“Most state solicitors have a background that suggests that they are or will become elite members of the legal profession.” Banks Miller, Describing the State Solicitors General, 93 Judicature 238, 239 (2010).

- 35As a former Texas state solicitor general put it, “there are some cases in which we are absolutely involved in the trial court from day one—when we know the case is going to turn into a bigger appellate case or become a more notable public law case.” Scott Keller, Federalism As A Check on Executive Authority: The Perspective of A State Solicitor General, 22 Tex. Rev. L. & Pol. 297, 298 (2018).

- 36For an in-depth discussion of the phenomenon, see Jonathan Remy Nash, Judicial Laterals, 70 Vand. L. Rev. 1911, 1914 (2017) (assembling “a novel database of movements by judges from a state judiciary to the federal judiciary, or from the federal judiciary to a state judiciary”).

- 37As even Justice Ginsburg has recognized. See David E. Pozen, The Irony of Judicial Elections, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 265, 315 (2008) (discussing Ginsburg’s concerns about the “rising politicization of state courts”).

- 38The phrase is associated with the great constitutional theorist Alexander Bickel, who worried about the democratic deficit created by overweening judicial governance. See Alexander Bickel, The Least Dangerous Branch: The Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics, 16–18 (2d ed. 1986).

- 39Ron Gilson and Robert Mnookin argued that this consistent culture would inculcate the same values in all of the lawyers at a firm, especially in the case of the leading firms. Ronald J. Gilson & Robert H. Mnookin, Sharing Among The Human Capitalists: An Economic Inquiry Into The Corporate Law Firm And How Partners Split Profits, 37 Stan. L. Rev. 313 (1985).

- 40“The “vast majority” of lawyers have engaged in private practice, as opposed to government service or public interest practice.” Russell G. Pearce, The Professionalism Paradigm Shift: Why Discarding Professional Ideology Will Improve the Conduct and Reputation of the Bar, 70 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1229, 1276 n.55 (1995).

- 41Criminal and prisoner appeals were the most common parts of the appellate docket for the year ending in March 2020, according to the data collected by the Administrative Office of U.S. Courts.