The Unexpected Role of Tax Salience in State Competition for Businesses

Competition among the states for mobile firms and the jobs and infrastructure they can bring is a well-known phenomenon. However, in recent years, a handful of states have added a mysterious new tool to their kit of incentives used in this competition. Unlike more traditional incentives, these new incentives—which this Article brands “customer-based incentives”—offer tax relief to a firm’s customers rather than directly to the firm. The puzzle underlying customer-based incentives is that tax relief provided to the firm’s customers would seem more difficult for the firm to capture than relief provided directly to the firm—strange, as a state’s primary goal is to subsidize the firm’s investment in the state.

After examining the emergence of this new form of incentive, this Article offers a novel explanation for its use and potential for success. Specifically, the Article argues that the effects of predictable consumer biases, particularly with respect to the salience of the tax relief provided by the incentives to consumers, cause customer-based incentives to differ substantively from traditional incentives in ways that are beneficial to both firms and states. Customer-based incentives thus present an example of how taxpayer behavior can influence the substantive effects of tax provisions, even causing two provisions with the same goal to differ on the ground. Taking these behavioral effects into account provides opportunities to increase the effectiveness of tax provisions.

Introduction

In 2012, Amazon agreed to invest $130 million in building two fulfillment centers and to create 1,500 jobs in New Jersey in exchange for the state relieving Amazon of its sales-tax-collection obligations.1 That New Jersey took action to lure Amazon into the state is unexceptional; states have long competed with each other over mobile firms by providing specific firms with targeted economic development incentives to encourage those firms to invest in the states.2 Until very recently, however, few, if any, states had provided such incentives in the form that New Jersey provided to Amazon,3 a form that this Article labels “customer-based” incentives. Instead, targeted economic development incentives have traditionally taken the form of such things as income tax credits and property tax abatements.4 For example, in 2013, New Jersey’s close neighbor Maryland provided Amazon with $43 million worth of tax credits in exchange for Amazon’s opening a one-million-square-foot distribution center and employing one thousand people in the state.5 Though “traditional incentives” like those provided by Maryland are unremarkable, customer-based incentives are anything but.

This Article introduces customer-based incentives to the academic literature by arguing for their remarkability and their place in states’ efforts to lure mobile firms and the jobs and infrastructure they bring. After providing an overview of how customer-based incentives function and the apparent oddity of their use, I argue that predictable consumer biases cause individuals to react to customer-based incentives in ways that make those incentives more effective at luring firms to the offering state and more beneficial to society as a whole than traditional incentives. This conclusion explains why the emergence of customer-based incentives is not so odd after all and, at a higher level, demonstrates that the form of a tax provision can affect its substantive consequences; policymakers can improve the efficiency and equity of tax provisions, particularly tax relief provisions, by incorporating the lessons of behavioral research into the design of those provisions.6

Customer-based incentives and traditional incentives represent two ways a state can achieve the substantive policy of encouraging a particular firm to invest in the state. Through traditional incentives, the state provides the firm with direct tax relief;7 through customer-based incentives, the state provides tax relief to the firm’s customers when they transact with the firm.8 The difference between customer-based incentives and traditional incentives may appear irrelevant when actors are economically rational; a firm can adjust its prices to capture as much of the tax relief provided through either form of incentive as it prefers.9 Further, when one relaxes the assumption of rational actors, there also seems to be a real danger to Amazon or any similarly situated firm that it would not be able to capture the tax relief from customer-based incentives; its customers might not tolerate the firm raising pretax prices to capture the relief. Research into consumers’ perceptions of fairness in pricing confirms the likelihood of this result; thus, the tax relief from customer-based incentives should be expected to stick with customers, at least to some degree.10 Thus, the emergence of customer-based incentives is somewhat mysterious; why break from the status quo of traditional incentives in favor of what appears to be a less firm-friendly form of incentive?

The effects of tax salience on consumer behavior provide an answer to this mystery. Tax salience refers to the level of awareness taxpayers have of a tax provision.11 Thus, when a consumer wants to spend $1,000 on a new laptop from Amazon but the additional $60 of sales tax stops her from doing so, that sales tax is salient to her. Research into tax salience demonstrates that many tax provisions—particularly sales taxes—may be “undersalient” to consumers; consumers ignore these taxes to some degree.12 Returning to that same consumer, when the sales tax is undersalient to her, she might completely ignore that $60 of sales tax and purchase the laptop anyway, even though she ultimately spends $1,060 and exceeds her preferred budget. Other tax provisions can be “hypersalient” to consumers, meaning that consumers overreact economically to the provisions.13 The laptop purchaser might perceive a hypersalient sales tax as the economic equivalent of $120 instead of $60, making her even less likely to purchase the laptop. However, if tax relief can be made hypersalient to consumers, then they will overreact to its economic value; $60 of sales tax relief might feel like $120 to the laptop purchaser, causing her great satisfaction when purchasing from a firm receiving customer-based incentives, such as Amazon.

Hypersalience of the tax relief from customer-based incentives may seem outlandish at first; however, consumers’ behavioral biases make it not only feasible but likely. For instance, research has demonstrated that people suffer from a behavior termed “tax-label aversion”—people value not paying something labeled a tax just for the mere fact that it is labeled a tax.14 Because customer-based incentives offer consumers tax relief, those incentives trigger consumers’ tax-label aversion. Therefore, a firm receiving customer-based incentives can promote sales-tax-free shopping and expect a bump in demand because people simply do not like taxes.15 Traditional incentives do not offer this advantage because consumers are unlikely to think they are being relieved of taxes, even if the firm lowers prices to pass along the tax relief from traditional incentives. This suggests that, when it can invoke tax-label aversion in its customers, a firm can get more of a benefit from customer-based incentives than traditional incentives, explaining why Amazon would request customer-based incentives.16

Any hypersalient tax relief provided through customer-based incentives should be expected to benefit not only firms but also states, further explaining the emergence of customer-based incentives. Customer-based incentives are likely to generate more benefits for society than traditional incentives, all else being equal. These societal benefits result primarily from two sources. First, because of tax-label aversion, consumers feel more satisfaction when shopping at a firm receiving customer-based incentives than they would otherwise.17 Second, because a firm receiving customer-based incentives is less likely to capture the tax relief offered than a firm receiving traditional incentives, customer-based incentives are more likely than traditional incentives to undo the harmful effects to society of the original taxes.18 Taxes reduce the amount of beneficial transactions in a society and thereby reduce overall social welfare. When customers retain the tax relief provided by the state, it is as though the original taxes were never imposed; society is restored to a pretax world. If the firm retains the tax relief, as can be expected to happen in the case of traditional incentives, society remains in the after-tax world and the harmful effects of taxation are not eliminated.19

States have additional reasons to potentially prefer customer-based incentives. A common concern regarding traditional incentives is the fear of the tax relief being used to finance activities outside of the state—that the money the state lays out will somehow “escape” the state by the firm’s actions.20 Because the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives is directly tied to in-state consumption, those incentives are not plagued by the escape issue.21 Also, customer-based incentives provide tax relief—even if only nominally—to anyone willing to shop from the recipient firm, which may make customer-based incentives more equitable in public opinion.22 However, certain customer-based incentives involve a form of selective nonenforcement of taxes by the state that may be perceived as particularly unfair and politically undesirable (though the states’ current experiences should soften this concern).23 Customer-based incentives may further increase social welfare if they are perceived as more equitable and less subject to abuse than traditional incentives, but, at a minimum, these additional aspects of customer-based incentives further demonstrate how such incentives can differ from traditional incentives.

In sum, the goals of this Article are twofold: first, to introduce customer-based incentives to the academic literature; and second, to use those incentives to demonstrate that the form of a tax provision can affect its substantive consequences. To these ends, the Article proceeds in four Parts. Part I details the different forms of targeted economic development incentives, providing an in-depth look at how customer-based incentives function and describing their recent emergence and potential for growth. Part II then questions the puzzling emergence of customer-based incentives, the benefits of which appear more difficult for a firm to capture than those arising from traditional incentives. Part III offers a solution to this puzzle: the salience of the tax relief from the two different forms of incentives affects the benefits they produce for firms in ways that make customer-based incentives more appealing than traditional incentives. Part IV then examines the potential benefits of customer-based incentives to states, providing a basis for why a state would prefer customer-based incentives to traditional incentives as a matter of policy.

I. The Different Forms of Targeted Economic Development Incentives

Targeted economic development incentives have long been a part of state government spending, as states compete for mobile firms and the jobs and infrastructure they bring.24 This Part provides a brief overview of such incentives before narrowing its focus to customer-based incentives. Traditionally, targeted economic development incentives have provided specific firms with direct tax relief through such things as income tax credits and property tax abatements, like Maryland provided to Amazon,25 or with subsidies through such things as state-sponsored job training programs and infrastructure construction.26 In exchange, the state offering the incentives often hopes to bring (or retain) jobs, investment in infrastructure, and economic growth to the state, along with the additional tax revenues that accompany such things.27

This Article focuses on targeted economic development incentives providing tax relief. The overarching ability of such incentives to influence mobile firms’ decisions is the topic of much debate,28 which I do not enter. The fact remains that most, if not all, states offer targeted economic development incentives. Though many commentators conclude that the incentives’ impact on firms’ decisions is relatively small, they tend to admit that states offer the incentives anyway due to the perceived high-stakes competition for jobs and other drivers of economic growth.29 Targeted economic development incentives providing tax relief can take a number of forms. Traditional incentives are relatively uncomplicated; through them, the state provides direct tax relief to the firm, and the firm is then free to take advantage of that tax relief however it prefers.30 In contrast, customer-based incentives do not provide direct tax relief to the firm but instead provide tax relief to the firm’s customers.

The remainder of this Part details customer-based incentives more closely by first examining how they function and then inspecting their recent emergence. Though customer-based incentives are not necessarily limited to the area of sales taxes, the discussion will focus on sales-tax-based, customer-based incentives given that these are the only type of customer-based incentives provided by states so far. For these purposes, there are no meaningful differences between how a state imposes its sales tax or between sales taxes and use taxes.31 Therefore, for ease of discussion, all sales taxes and use taxes will collectively be referred to as “sales taxes.”

A. How Customer-Based Incentives Work

Understanding how customer-based incentives operate provides the necessary background for considering how they differ from traditional incentives. There are three parties directly involved in the provision of a customer-based incentive: the state, the firm, and the firm’s customers.32 The state provides the customer-based incentive, the firm receives the customer-based incentive, and the firm’s customers are relieved of their obligation to pay taxes on purchases from the firm. This tax relief for the firm’s customers is the defining attribute of a customer-based incentive, and it can conceivably take two forms: direct relief of the taxes imposed on purchases from the firm, and indirect relief from taxes. Customer-based incentives providing the former will be referred to as “direct customer-based incentives,” and those providing the latter as “indirect customer-based incentives.” The primary benefits of customer-based incentives—direct or indirect—to the firm are straightforward. Beyond the administrative cost savings that come with not having to collect sales taxes,33 the firm receives the competitive advantage of being physically present in the state34 and its customers not having to pay sales taxes on their purchases from it.35 This competitive advantage may result in both more customers and more profits per customer if the firm also raises its pretax prices to capture some of the tax relief offered by the incentives.

Direct customer-based incentives are rare, if not nonexistent. Such incentives presumably would be provided through statutory or regulatory language exempting purchases from a certain firm from sales taxes.36 In this scenario, there would be no sales tax owed on transactions with the firm, so the firm would not collect any taxes. Though direct customer-based incentives are rare, direct relief of sales taxes is not a foreign concept; such relief can be found in the statutes of all of the forty-five states (and the District of Columbia) that impose sales taxes. For example, exemptions for or lower tax rates on purchases of groceries,37 purchases from nonprofit organizations,38 or purchases in designated enterprise zones39 all provide direct tax relief to consumers. Though the goals of these exemptions may not always be economic development, they encourage consumers to buy groceries instead of restaurant meals, to buy from nonprofit instead of for-profit organizations, and to shop in enterprise zones instead of outside the zones. Enterprise zones—designated areas in which a state lowers tax rates and business regulations in an effort to stimulate economic growth and employment40 —offer a good example of direct tax relief for economic development purposes that direct customer-based incentives might imitate in a more targeted way. Indeed, enterprise zones provide a possible starting point from which direct customer-based incentives might evolve should states desire to venture into offering such incentives.41

In contrast, a state provides indirect customer-based incentives by relieving the firm of its obligation to collect sales taxes. Thus, the state does not formally relieve the firm’s customers of their obligations to pay sales taxes (the taxes are still owed), but instead the firm never collects the taxes, effectively relieving the customers of the taxes. This effective tax relief arises because individual compliance with sales tax obligations—technically, use tax obligations—is dismally low when a vendor does not collect the taxes at the time of sale, and the states’ efforts to overcome this low level of compliance have been largely ineffective.42 Thus, in the current state of affairs, if a vendor does not collect sales tax from an individual, the sales tax will not be paid; relieving firms of their sales-tax-collection obligations results in sales tax relief for their customers.

Though indirect customer-based incentives are a new phenomenon, most consumers have enjoyed a form of indirect tax relief for some time. Under Supreme Court precedent, remote vendors—vendors without a physical presence in the taxing state, such as online and mail-order vendors—are beyond the states’ taxing authority.43 Remote vendors do not collect sales taxes from their customers because they are not obligated to.44 And because individual consumers do not self-report and pay their sales taxes on their purchases from remote vendors, the consumers receive indirect tax relief on those purchases.45 According to one study, consumers’ failure to self-report and pay sales taxes not collected by online vendors contributed to an estimated $11.4 billion in lost revenues among all states in 2012.46 Anyone who has made a purchase online on which sales tax was not collected and who did not subsequently pay the tax has experienced this unintentional form of indirect tax relief, albeit by breaking the law.

B. The Emergence of Indirect Customer-Based Incentives

Though the future of indirect sales tax relief for purchases from remote vendors is unclear,47 indirect customer-based incentives are emerging. This Section examines this emergence and argues that such incentives are poised to grow in usage as a practical matter. In recent years, a handful of states have provided Amazon with indirect customer-based incentives by agreeing to delay the enforcement of Amazon’s sales-tax-collection obligations in exchange for Amazon’s commitment to create and maintain a certain number of jobs in the states and to invest certain amounts in facilities in the states.48 The states do not appear to have provided customer-based incentives (direct or indirect) to any firm other than Amazon yet;49 however, their use is ripe for analysis given their recent emergence.

That Amazon is the first mover does not mean that it is the sole candidate for customer-based incentives; other firms would benefit from them as well, and states should be expected to offer them to other firms as the potential benefits of the incentives—discussed in the following parts—become clearer.50 Even so, widespread use of the incentives might not be expected for a number of practical reasons. First, sales-tax-based, customer-based incentives necessarily have a diminishing return as more are offered. The competitive advantage that arises from the incentives relies on the firm not collecting sales taxes even though its competitors do.51 The higher the percentage of competitors collecting sales taxes, the larger the competitive advantage will be. While customer-based incentives will likely never reach the scale of traditional incentives, they can be tailored to address this problem. For one thing, they can be offered on a temporary basis, allowing the state to shift the incentives among firms over time.52 This might increase competition for the incentives, improving the advantages states receive in return. It might also decrease the value of the customer-based incentives to the first firm to receive them if the customer loyalty it gained is diminished by the sales-tax-free shopping made available elsewhere.53 A better solution to the problem of diminishing returns may be to limit the customer-based incentives geographically, to allow for multiple firms to receive them simultaneously in one state. Thus, customer-based incentives might best be administered on a local level.

Additionally, the reason a firm is seeking out targeted economic development incentives may affect whether customer-based incentives are appealing. If the firm needs predictable assistance in order to invest in the state, then customer-based incentives will not be as effective in luring the firm as traditional incentives because customer-based incentives do not provide block grants of known tax relief—the firm must engage in commercial activity before it sees any benefit from customer-based incentives and the size of that benefit remains uncertain. However, if the firm is looking to increase its returns, customer-based incentives may be appealing as they are not as concrete as traditional incentives tend to be—the more commercial activity the firm engages in, the higher the benefit from customer-based incentives. There is the potential that the benefit for the firm from the customer-based incentives will be larger than the set amount provided by traditional incentives.54

Finally, customer-based incentives appear to have a limited universe of potential recipients—vendors responsible for collecting sales taxes. However, this does not have to be the case. One can conceive of a state offering people income tax credits for engaging in transactions with a particular firm; similar general incentives are made available by the federal government for purchasing energy-efficient goods.55 What is important to the customer-based incentive form is that tax relief is provided to someone that interacts with a firm as a result of that very interaction with the firm. The firm may then figure out how to capture some of that tax relief if it pleases. Creative policymakers should be able to find ways to create customer-based incentives in a variety of contexts.

Thus, many of the practical limitations on the growth of customer-based incentives are not insurmountable. Customer-based incentives will likely never fully replace traditional incentives, but there is no reason that a state could not provide both to a firm. Policymakers should thus invest time in better understanding how the incentives work and ways to make them more effective.

II. The Puzzle of Customer-Based Incentives

Though customer-based incentives appear primed to take on a larger role in states’ economic development efforts, whether states should actually expand their use of such incentives may—or, at least, should—depend on whether the difference in form between customer-based incentives and traditional incentives has substantive effects. Otherwise, the simple administrative costs of adopting a new form of incentive should cause states to prefer to continue relying on traditional incentives. Before the next Parts analyze the potential benefits of customer-based incentives over traditional incentives, this Part argues that at least one difference between the two types of incentives makes the emergence of customer-based incentives appear quite odd. Because of predictable consumer biases regarding fairness and losses, firms should be expected to have more difficulty capturing the tax relief offered through customer-based incentives than that offered through traditional incentives.

The fact that customer-based incentives provide tax relief to a firm’s customers rather than directly to the firm does not necessarily mean that the firm will not receive any of the economic value of that tax relief. Because the taxes relieved are still levied generally, market prices should continue to reflect after-tax prices if the marketplace is competitive. If the firm controls its prices after receiving the incentives, it can keep them at the after-tax, pre-incentives level, capturing the full benefit of the tax relief.56 The ability of the firm to control prices depends on its relative competitive position to consumers.57 One of the key characteristics of targeted economic development incentives is that they provide firms with a competitive advantage by lowering their costs of doing business or the costs of doing business with them; therefore, it is assumed that the firms have strong competitive positions vis-à-vis their customers, as those firms are the only ones able to offer lower after-tax prices.58 Thus, firms receiving targeted economic development incentives may be expected to control the post-incentives prices of what they sell.

If it is assumed that the firm’s ability to control prices is entirely unimpeded, then there is no reason to think that the firm’s ability to capture tax relief provided through customer-based incentives is meaningfully different than its ability to capture tax relief provided through traditional incentives. Numerous theories have demonstrated that, when rational actors and no transaction costs are involved, the initial distribution of rights (or benefits, or burdens, etc.) among parties should not matter; the parties will transact with each other to reach their preferred balance of rights.59 It is not surprising that the form of targeted economic development incentives should not matter under the same assumptions; the firm will be able to adjust pricing to reach its preferred balance. However, relaxing the assumption that a firm has entirely unimpeded control over prices after receiving targeted economic development incentives introduces some stickiness to the pre-incentives prices. In other words, when the firm faces transaction costs to changing its prices, pre-incentives prices should be expected to remain in effect until the value of the tax relief captured by changing prices outweighs the transaction costs. Two major transaction costs to firms in adjusting their prices are considered here: the costs imposed by the fairness concerns of consumers and the costs imposed by the pain consumers feel from losing tax relief to which they feel entitled.60

A. The Fairness of Pricing Changes

Research demonstrates that people value being treated fairly and are willing to suffer economic harm to themselves in order to punish those they perceive to be acting unfairly.61 Perhaps the most well-known research in this area involves the ultimatum game experiment.62 In this experiment, two participants are given the opportunity to share a sum of money; one participant proposes a distribution between the two, and the other participant may either accept or reject the proposal.63 If the proposal is accepted, both participants get their proposed share of the money; if the proposal is rejected, neither participant receives anything.64 Contrary to the expectations of rational actor theory, participants routinely reject low-ball offers—they are willing to suffer economic harm to avoid being treated unfairly and to punish the first participant for making an unfair proposal.65 More complex iterations of the ultimatum game reach similar results.66 This suggests that if a firm is perceived as unfairly adjusting (or not adjusting) its prices after receiving targeted economic development incentives, customers may punish the firm by refusing to shop with it.67 A firm should therefore consider how consumers can be expected to react to price changes in response to the receipt of incentives and the potential costs of establishing unfair prices.68

Researchers have studied how consumers judge the fairness of price changes. In one influential study, Professors Daniel Kahneman, Jack Knetsch, and Richard Thaler conducted a series of telephone surveys in which they posed a number of scenarios to consumers to determine how the consumers judged the fairness of different pricing practices.69 This research demonstrated that consumers tend to judge the fairness of pricing changes based on the interaction of two reference points: the firm’s reference profit and the customer’s reference price.70 These reference points are established prior to the proposed change;71 for purposes of this analysis, it is assumed that the pre-incentives profit and price are the appropriate reference points (though as developed below, what exactly the pre-incentives price is in consumers’ minds is not clear). Further, the research demonstrates that customers feel entitled to their reference prices but permit firms to protect their reference profits at the expense of the reference prices;72 thus, it is perceived as fair for a firm to increase prices as the result of increased costs of doing business, but it is perceived as unfair for a firm to increase prices due to increased market power.73 Interestingly, people judge it fair for a firm to maintain prices even if its costs of doing business decrease.74 Thus, people expect to be charged the reference price, and fairness requires only that the firm not take advantage of increased market power to raise prices.

What do these findings mean in the context of targeted economic development incentives? Certainly, consumers are not going to object on fairness grounds to a firm lowering its prices. But will the firm face pushback for maintaining after-tax, pre-incentives prices? Traditional incentives provide direct tax relief to the firm, lowering its costs of doing business; thus, consumers’ fairness concerns should not affect the ability of a firm receiving such incentives to maintain pre-incentives prices and thereby increase its profits. For example, suppose a jeans-selling firm receives a traditional incentive. Prior to receiving the incentive, it sold jeans to Amy for a price of $100 and generated a profit of $20. The firm’s reference profit is $20, and Amy’s reference price is $100. If the traditional incentive provided the equivalent of $10 of tax relief for each sale, the firm would be able to maintain the $100 reference price and increase its profit to $30 on each sale without offending the fairness sensibilities of its customers—it would not be pressured to pass along a portion of the tax relief to its customers. Assuming a 5 percent sales tax, Amy would pay $105 total for her jeans regardless of whether the firm receives the traditional incentive. One might expect the $105 after-tax price to be Amy’s reference price, but whether Amy’s reference price is $100 (the pretax price) or $105 is irrelevant; when the firm maintains its pretax price, the after-tax price is the same as well.

On the other hand, maintaining after-tax prices after receiving customer-based incentives may trigger fairness concerns in consumers. This result will occur if consumers view the pretax price instead of the after-tax price as the reference price. Because customer-based incentives eliminate the sales taxes consumers pay, maintaining the pretax price does not result in the same after-tax price; to maintain the after-tax price and capture the tax relief, the firm would need to increase the pretax price it charges. As the firm faces no threat to its reference profit as a result of the customer-based incentives, consumers will be unwilling to sacrifice their reference price; the increase in the pretax price will be rejected on fairness grounds.

When consumers do not pay attention to sales taxes, the consumers should be expected to think of the pretax price as the reference price, as that is the price the consumers are basing their decisions on.75 Research into “tax salience”—which has garnered increasing amounts of academic attention in recent years76 —demonstrates that consumers often fail to fully take sales taxes into account before making purchasing decisions.77 Tax salience refers to the level of awareness a taxpayer has of a tax provision.78 This concept can be split into two components: first, awareness of the economic effects of the tax provision—“market salience”—and second, awareness that the tax provision is the source of those economic effects—“practical salience.”79 Though market salience, which the next Part returns to in further detail, and practical salience, which the next Section examines in more detail, are related and may inform one another, they are distinct concepts.80 To illustrate the difference between them, consider the example of liquor excise taxes which are included in the posted price of the liquor rather than separately stated. Professors Raj Chetty, Adam Looney, and Kory Kroft found that consumers responded economically to such taxes as one would rationally expect them to respond—an increase in tax lead to a proportionate decrease in demand.81 Thus, the excise taxes were fully market salient to the consumers. However, the researchers also found that the liquor consumers were not aware that the excise taxes were the source of price increases, blaming the business for the increases instead of the taxing state.82 This result indicates that the taxes were not practically salient to the consumers.

The tax salience research indicates that a firm receiving traditional incentives will not face fairness transaction costs when maintaining its pretax prices to capture the tax relief provided, but that a firm receiving customer-based incentives (at least sales-tax-based ones) may if it must raise pretax prices to capture the tax relief provided. Unless consumers can be convinced to adopt after-tax prices as their reference prices, the firm is less likely to capture the tax relief from customer-based incentives than that from traditional incentives. However, even if sales taxes become salient to consumers such that after-tax prices become their reference price, another bias—loss aversion—may hinder the firm’s ability to capture tax relief from customer-based incentives.

B. Practical Salience and Loss Aversion

As noted, practical salience refers to the awareness that a tax provision is the source of economic effects that a person experiences.83 If a tax provision is practically salient to a person, the person should be expected to react to the provision in such ways as protecting or attacking it both politically and in their interactions with nonpolitical actors.84 Exactly how tax provisions become practically salient and how people will react to practically salient taxes are often difficult things to predict.85 People are motivated to take action for a number of reasons, of which the practical salience of tax provisions is only one.86 Even so, this Section discusses different reactions that can be expected to arise from the practical salience of tax relief from the different forms of targeted economic development incentives, arguing that the lower practical salience of tax relief from indirect customer-based incentives than that from direct customer-based incentives explains why firms would prefer tax-collection-obligation relief rather than direct tax relief for their customers.

Studies indicate that factors affecting the practical salience of a tax provision include the burden the provision places on the taxpayer, particularly in terms of compliance;87 the transparency of how the provision works;88 and whether the provision directly falls on the taxpayer.89 Thus, the market salience of a tax provision is likely to inform its practical salience; if a taxpayer realizes the economic burden of the tax, the tax provision is more conspicuous than if the burden were not noticed. However, market salience does not fully define practical salience; even tax provisions that have a high degree of market salience may have a low degree of practical salience.90 Consider the excise taxes on liquor discussed earlier; the excise taxes were market salient but were not practically salient.91 Liquor consumers dissatisfied with the high price of liquor might not understand that a source of their dissatisfaction is the excise taxes, and therefore the consumers might not react to the taxes practically.

Tax relief from the different forms of targeted economic development incentives should be expected to have different levels of practical salience for consumers. Some basic level of practical salience of tax relief provided by targeted economic development incentives should exist for consumers; watchdog groups and government agencies issue reports regarding such incentives that spur people to take action for or against them.92 However, tax relief from traditional incentives should be less practically salient to consumers than relief from customer-based incentives because the tax relief from traditional incentives does not directly fall to consumers. Further, indirect customer-based incentives should be less practically salient to consumers than direct customer-based incentives because, although the tax relief from indirect customer-based incentives is directly experienced by the consumers, the process by which consumers receive that relief is not as transparent as the process behind tax relief provided through direct customer-based incentives.93 Thus, on a scale, traditional incentives will have the least amount of practical salience to consumers, indirect customer-based incentives will fall in the middle, and direct customer-based incentives will have the highest amount of practical salience, all else being equal.94

The lower practical salience to consumers of traditional incentives and indirect customer-based incentives may cause consumers to fail to perceive the full extent to which those incentives are the source of tax relief that flows through to them. On the other hand, the higher practical salience of direct customer-based incentives to consumers should cause consumers to be more aware that the tax relief they receive comes from those incentives. The practical salience levels of the various forms of targeted economic incentives are important because of a behavior known as loss aversion—reacting more strongly to losses than gains from the status quo.95

Research has demonstrated that people commonly display loss aversion, iterations of which are referred to as the endowment effect or the status quo bias.96 In one of the most famous experiments, researchers gave mugs to some participants and nothing to others.97 They then asked the participants how much money they would be willing to accept to part with the mugs and how much money they would be willing to pay to acquire a mug, respectively. The values placed on the mugs by those who were given them were significantly higher than the prices others were willing to pay to acquire them. When the roles were switched, the same people who earlier had placed higher values on the mugs they possessed indicated that they would not pay as much to acquire a mug, demonstrating that people place a higher value on losing things already possessed than gaining the same things. In the tax context, Professors Edward McCaffery and Jonathan Baron have demonstrated that people suffer from a form of loss aversion they term “penalty aversion”—people prefer things labeled bonuses, such as a child bonus, which come across as gains, to things labeled penalties, such as a childless penalty, which come across as losses, even if the end results are the same.98

When consumers view the status quo as the tax relief from targeted economic development incentives falling to them, loss aversion will inhibit the firm’s ability to capture that tax relief; the firm’s price increases would decrease demand for its goods more than expected as customers feel the pain of losing the tax relief they thought was theirs. The additional practical salience to consumers of the tax relief provided through direct customer-based incentives makes consumers more likely to view their receiving that tax relief as the status quo. On the other hand, because traditional incentives and indirect customer-based incentives frame the relief provided as that of the firm (either direct tax relief or the relief of a collection obligation), the tax relief consumers receive through those incentives appears as a gain to consumers instead of a loss.99 The status quo in these instances is the firm receiving an incentive and the customer paying sales tax. Further, statutory incidence can go a long way in defining the status quo;100 though a firm could conceivably promote its nonobligation to collect sales taxes when it receives either direct or indirect customer-based incentives, granting that collection relief to the firm on the books makes people more likely to view the status quo as the firm receiving a benefit.

Thus, because indirect customer-based incentives inhibit the impact of loss aversion, firms should be expected to prefer them over direct customer-based incentives. However, the mystery of why a firm would prefer customer-based incentives over traditional incentives in the first place still remains; unlike customer-based incentives, traditional incentives should trigger neither loss aversion nor fairness concerns in consumers. The following Part provides an explanation for this mystery by arguing that customer-based incentives provide a larger benefit to firms than traditional incentives, even if the firm is unable to capture the actual tax relief provided through the incentives.

III. The Tax Salience Solution to the Customer-Based Incentives Puzzle

State policymakers can implement their substantive policy goals in a variety of forms. For instance, a state wishing to encourage economic development by convincing a firm to invest in the state can provide that firm with traditional incentives or customer-based incentives (or some mix of the two). Without passing judgment on the effectiveness of targeted economic development incentives generally, this Part uses such incentives as a case study to demonstrate that the choice of a tax provision’s form is significant; different forms of taxation intending to implement the same policy can generate different substantive effects because they have different levels of salience to consumers. In particular, differing levels of market salience—the awareness of a tax provision that affects a person’s economic decision-making101 —should cause consumers to react more strongly to the tax relief provided through customer-based incentives than that from traditional incentives. Coupled with the preference for indirect customer-based incentives detailed in the prior Part, this result provides a solution to the puzzling emergence of indirect customer-based incentives.102

A. The Degrees of Market Salience

As alluded to, recent research has demonstrated that tax provisions have differing levels of market salience to taxpayers.103 Tax provisions can be undersalient, fully salient, or hypersalient.104 The idea of full salience serves as a baseline for measuring when a tax provision is undersalient or hypersalient—tax provisions that are fully salient to a taxpayer have rationally expected effects on the taxpayer’s economic decision-making. In contrast, tax provisions that are undersalient have smaller-than-expected effects on the economic actions of those affected,105 and tax provisions that are hypersalient have greater-than-expected effects.106

Theory suggests that a behavior termed “spotlighting” affects the market salience of a particular tax provision to the taxpayer.107 Spotlighting refers to the tendency of a person to focus on particularly conspicuous components of a price or transaction to the exclusion of other components, thereby misperceiving the total cost of the transaction.108 Thus, taxes paid manually by the taxpayer are more salient than taxes paid automatically,109 immediate taxes are more salient than delayed taxes,110 and aggregated taxes are more salient than broken-up taxes,111 all because the total cost of the tax becomes more conspicuous.

Sales taxes are a prime example of taxes that may be undersalient; consumers spotlight on tax-free posted prices and ignore the cost of the taxes.112 For example, in one of the more well-known studies, Professors Chetty, Looney, and Kroft ran a three-week-long experiment in grocery stores in which they included the sales tax in the posted price of goods on the shelves.113 This action caused a decrease in sales of the goods, indicating that people had not been paying full attention to the taxes before they were included but instead had spotlighted on the tax-free posted prices. The act of spotlighting on nontax elements of a price or a transaction alone does not necessarily mean that the tax will be undersalient to the parties involved.114 After all, a consumer that spotlights on pretax prices could be aware of the tax generally (that is, it could be practically salient to the consumer) but overestimate its burden. For example, Chetty, Looney, and Kroft posit that the market salience effects they observed in their grocery store experiment derived from consumers believing that calculating the burden of the taxes would be too costly, so they instead ignored the taxes and focused on posted prices.115 This theory requires the consumer to know about the tax but to underreact to it.

At least two predictable behaviors contribute to the likelihood that an ignored tax will become undersalient. First, people display “anchoring bias” when making estimates of unknown values.116 Anchoring causes a person’s estimates to gravitate toward a conspicuous number, even if that number has nothing to do with what is being estimated.117 For instance, in one study, people were asked to spin a wheel numbered 0 to 100 and then estimate various percentages, such as the percentage of African countries in the United Nations.118 Despite the clear arbitrariness of the numbers on the wheel, people’s estimates gravitated toward the number they spun.119 When consumers spotlight on pretax prices, those prices will set an anchor for their estimates of the tax they will owe, causing the consumers to underestimate the taxes.120

Additionally, people display “optimism bias,” which causes them to underestimate the likelihood of losses and overestimate that of gains.121 For example, optimism bias may lead consumers to disregard consumer product safety warnings because the consumers undervalue the possible harms from the product.122 An optimistic consumer that has not calculated the actual value of the taxes that she will owe may similarly underestimate that value.123 However, most of the research on optimism bias focuses on relative risks—the risk an individual faces when compared to other people—and taxes may not fit this mold, potentially weakening the expected effect of optimism bias in the context of the market salience of tax provisions.124 Even so, if a consumer is considering the probability that a certain tax rate will apply, she may be inclined to expect a lower tax rate due to optimism bias.

It should be noted that the research on the salience of sales taxes has focused primarily on shopping in physical stores, not over the Internet.125 As noted, Chetty, Looney, and Kroft theorized that calculating the burden of the taxes would be too costly for consumers, leading them to ignore the taxes and focus on posted prices.126 Education is thought to be one of the primary methods of making taxes more salient,127 and the Internet offers vendors the ability to make sales taxes more salient by offering quick information on after-tax prices, reducing consumers’ calculation costs and making the taxes more immediate.128 Therefore, sales taxes may be more salient on Internet purchases, though the taxes can remain broken up and not necessarily immediately available (they may not show up until the customer goes to a checkout page having already made the decision to buy), so some undersalience concerns may still exist.

Finally, some tax provisions may be hypersalient, affecting taxpayers’ economic actions to a greater degree than expected from rational actors.129 The deduction for charitable contributions has been described as hypersalient because it encourages taxpayers who are not eligible to claim the deduction to make charitable contributions; taxpayers spotlight on the deduction, ignoring the limitations on claiming it.130 As a result, people make more charitable contributions than might be rationally expected from an economic point of view.

This market salience research indicates two ways that the forms of targeted economic development incentives can affect firms differently. First, as discussed above, when consumers adopt pretax prices as reference prices because sales taxes are undersalient to them, firms will have difficulty capturing tax relief from customer-based incentives because of consumers’ fairness concerns.131 Second, if either form of targeted economic development incentives is undersalient or hypersalient to consumers or to firms, then their responses to those incentives will not meet economically rational expectations. The following sections explain why tax relief from customer-based incentives should be hypersalient to consumers but tax relief from traditional incentives should not, causing customer-based incentives to generate more demand for the firm’s goods.

B. The Market Salience of Tax Relief from Targeted Economic Development Incentives to Consumers

Because firms control prices, they also control the amount of tax relief that consumers receive;132 it is the market salience of this amount of tax relief to consumers that is important. If the firm passes no tax relief onto consumers, then there is nothing for the consumers to be aware of and react to economically. The tax relief from the different forms of targeted economic development incentives that is passed on to consumers can be expected to have different levels of market salience to consumers; relief from traditional incentives should be fully salient, but relief from customer-based incentives should have some degree of hypersalience. This difference in salience is what causes customer-based incentives to generate more demand for the firm’s goods than traditional incentives.

The tax relief from traditional incentives should be fully market salient to consumers because when a firm lowers its prices to pass along the tax relief, the economic effect of the relief is immediately available and visible to consumers. There is no need to self-compute the value of the tax relief, nor is the relief disaggregated or delayed. In short, the value of the tax relief is not economically hidden in any way from consumers (they may not realize that the tax relief is the source of the price decreases, but that misperception relates to practical salience, not market salience). Recall again the excise taxes on liquor studied by Chetty, Looney, and Kroft: these taxes were not separately stated to consumers, but instead were included in the posted price of the liquor. This inclusion made the taxes fully market salient—consumers’ preferences responded to increases in the taxes as expected.133

On the other hand, the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives could realistically be undersalient, fully salient, or hypersalient to consumers. However, because consumers are predisposed to finding tax relief hypersalient, as discussed below, and it is in both the state’s and the firm’s interest for consumers to find that tax relief hypersalient,134 hypersalience is the expected result.

Consumers might find the tax relief from customer-based incentives undersalient through the same mechanisms that they find certain sales taxes undersalient. When consumers spotlight on pretax prices and make their purchasing decisions before being exposed to taxes, they underestimate the value of those taxes.135 Like those taxes, the tax relief from customer-based incentives is not immediate and could be overlooked by a consumer spotlighting on pretax prices. Though the consumer may be pleasantly surprised to find that she received tax relief for taxes she was not paying attention to, that tax relief would not affect her economic decision-making.

Similarly, the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives might be fully salient to consumers in the same way that other sales taxes are fully salient.136 As noted, Chetty, Looney, and Kroft posit that spotlighting on pretax prices occurs because consumers think that the personal cost of calculating after-tax prices is too high for the benefit obtained.137 However, consumers could be easily debiased by providing them with information on after-tax prices prior to their decision-making process through such mechanisms as posting after-tax prices in stores or displaying a tax calculator or after-tax prices online.138 Providing consumers with immediate information on post-incentive prices or the explicit amount of tax relief provided to them should make that tax relief fully salient.

Finally, consumers could find the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives hypersalient—they might overreact economically to the tax relief. This result may seem fanciful initially, but consumers are primed toward this result because of two behaviors: tax-label aversion and optimism bias. Research demonstrates that people are affected by tax aversion—they have negative preferences for taxes.139 A subcategory of tax aversion is tax-label aversion, in which people value the relief of charges labeled taxes; the tax label itself affects people’s preferences.140 For example, Professors Abigail Sussman and Christopher Olivola, through a series of surveys, found that people were (i) more likely to drive thirty minutes out of their way to buy a television sales-tax-free than to drive the same distance for a slightly larger price discount, (ii) willing to stand in line longer for a tax-free purchase than an identically discounted purchase with tax, and (iii) more likely to prefer tax-free municipal bonds than other bonds, even when the final economic return was equivalent.141 Other commentators have observed overconsumption resulting from sales tax holidays offered by states.142 The satisfaction people feel from avoiding taxes adds to their desire to transact with a firm receiving customer-based incentives, causing what appears to be an overreaction to the actual value of the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives. All the firm needs to do to enjoy the resulting increased demand is make the consumers aware that they can shop sales-tax-free if they shop with the firm.143 In this vein, many online vendors have promoted sales-tax-free Internet shopping as a major reason to purchase from them instead of local vendors.144

In addition, if the consumer understands that she will be receiving sales tax relief, but does not precisely know the amount of the relief, the consumer’s optimism bias may cause her to overestimate the value of the tax relief. As noted, this bias causes people to underestimate losses and to overestimate gains.145 Thus, for any given reference price, consumers can be expected to underestimate the losses from having to pay sales taxes and to overestimate the gains from the tax relief provided if they understand that such taxes and tax relief will be in place but do not know the value of those things. The same actions a firm takes to trigger its customers’ tax-label aversion could also trigger this overestimation of the relief if the firm avoids providing any hard numbers regarding the amount of tax relieved.146 Further, assuming the customer is focusing on the idea of receiving tax relief, anchoring bias may not affect the consumer’s estimation of the tax relief because there is no initial value given to the consumer on which to anchor.147 However, a consumer might anchor to posted prices if the idea of tax relief is not conspicuous enough; this result might lessen the hypersalience of the tax relief.

Though the actual scale of the hypersalience of tax relief from customer-based incentives is uncertain, because research indicates that consumers can—and are likely to—find such tax relief hypersalient, customer-based incentives can be expected to generate more benefit for the firm than traditional incentives.148 In fact, the firm may benefit without altering its prices at all (though the option to do so remains); it can maintain reference prices and still be more competitive than its peers.149 The increased demand for the firm’s goods resulting from any hypersalience of customer-based incentives’ tax relief thus should lead the firm to prefer customer-based incentives over traditional incentives of the same amount.150 For a firm like a remote vendor, already experiencing the effects of such hypersalience, customer-based incentives offer the opportunity to maintain that status quo after investing in the state;151 traditional incentives do not.

C. The Market Salience of Tax Relief from Targeted Economic Development Incentives to Firms

Might the market salience of tax relief from targeted economic development incentives to firms affect which form is preferable? This Section argues that, because firms’ economic reactions to the two forms of targeted economic development incentives are likely to be similar, those reactions should not lead to the forms generating different effects. When discussing the firm’s economic reactions to the various incentives, it is more accurate to consider the reactions of the managers, owners, and customers of the firm, as the firm itself does not have awareness.152 The reactions of the customers were discussed in the prior Section.

The market salience of the tax relief provided through traditional incentives is unlikely to be misperceived by the managers of the recipient firm because the relief is negotiated, direct, and immediate.153 The negotiation process offers the managers the opportunity to overcome any existing misconception of the firm’s tax burden by requiring them to consider the value of the tax relief being offered (and thus the initial tax imposed), as well as any limitations on it. Further, the managers’ rationally expected response to the tax relief is buoyed by the fact that the relief is provided directly to the firm and is immediate in the sense that the managers are aware of it prior to making any business location decisions and pricing decisions. Similar to the case with traditional incentives, tax relief from customer-based incentives should be fully salient to the firm’s managers. Though the tax relief is not provided directly to the firm, its value is not obscured to the managers by that fact because the firm must negotiate for the incentives and the incentives are also immediate.

In the same way that consumers should be expected to find the tax relief from traditional incentives fully market salient—because the relief is passed along to them through changes to posted prices154 —a firm’s owners should find the tax relief from either form of targeted economic development incentives to be fully market salient. Neither form of incentives causes tax relief to fall directly to the owners; relief is passed through to them only in the form of dividends or changes to the value of their ownership interests. These objective measures of value offer little opportunity for owners to misperceive the economic value of the tax relief provided to their firms. Thus, no differences arise in how either form economically affects firms as a result of their behavior because managers and owners of firms should be expected to react similarly to both forms of incentives.155 Therefore, firms’ preference for customer-based incentives should remain intact.

IV. Customer-Based Incentives as Sound Policy?

Firms may prefer customer-based incentives, but what advantages might customer-based incentives offer states?156 This Part argues that customer-based incentives have the ability to generate more benefits for society than traditional incentives because consumers feel more satisfaction from the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives and because customer-based incentives are more likely to reduce the negative effects of the taxes they relieve. Further, there are strong reasons to believe that customer-based incentives will be seen as more equitable than traditional incentives because of the way they provide tax relief, strengthening the case for states to prefer customer-based incentives. To these ends, this Part addresses three significant issues that the form of the incentives might affect: the social welfare each form might generate, the “escape” of tax relief from the state’s economy, and the erosion of civic virtue that results from the nonenforcement of tax laws.157

A. The Effects of Targeted Economic Development Incentives on Social Welfare

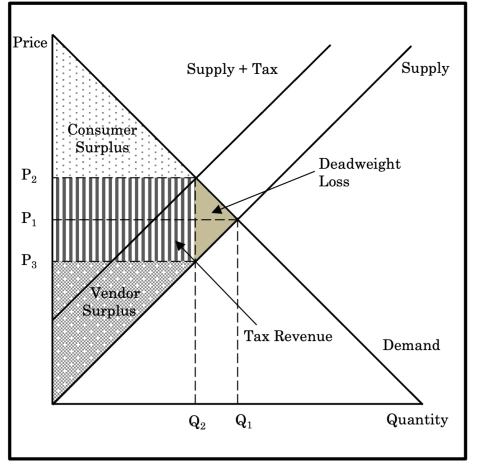

An issue for states to consider when deciding what form of targeted economic development incentive to offer a firm is the potential effects of the different forms on social welfare. Social welfare refers to the overall well-being of society—the accumulation of the benefits generated by interactions within society.158 Tax provisions typically diminish the amount of social welfare by generating what is referred to as “deadweight loss”—the social welfare lost because the cost of taxes causes people to stop engaging in otherwise-beneficial transactions.159 Figure 1 presents a basic graphical representation of these concepts: the “vendor surplus” represents the benefits the vendor receives from selling a good; the “consumer surplus” represents the satisfaction the customer receives from purchasing the good; in combination, the vendor surplus and consumer surplus represent the total amount of social welfare generated; the “deadweight loss” triangle represents the social welfare lost because of the additional cost of taxes imposed on the sale of the good, and the “tax revenue” rectangle represents the amounts of vendor surplus and consumer surplus that the state claims through the taxes. Tax provisions can also affect the distribution of social welfare among the members of society either progressively (redistributing from the better-off to the worse-off), regressively (redistributing from the worse-off to the better-off), or proportionally (not redistributing at all).160

Figure 1. Social Welfare with Tax Provisions

In general, policymakers should prefer policies that maximize social welfare and that distribute that welfare in an equitable manner,161 and this Section is devoted to showing that traditional incentives and customer-based incentives can generate different effects on social welfare solely as a result of their different forms. This is a critical insight because it shows that form matters when implementing substantive tax policy; a state can improve social welfare by carefully designing a tax provision. In order to focus solely on the expected effects on social welfare of the form of the incentives, this Section relies on two key assumptions. First, it is assumed that the different forms of targeted economic development incentives are equally effective at achieving the goal of boosting the state’s economy by creating jobs, encouraging investments in infrastructure, and enlarging economic activity.162 That is to say, a dollar of tax relief provided through a traditional incentive will result in the same amount of economic growth as a dollar of tax relief provided through a customer-based incentive. A corollary to this assumption is that the two forms of incentives will bring the same amount of economic detriment to the recipient’s competitors.163 Second, it is assumed that a state providing targeted economic development incentives will respond in the same way to its reduced tax revenues regardless of the form which those incentives take. In other words, to finance the incentives, the state will cut spending or raise taxes in the same way for traditional incentives and customer-based incentives. Under these assumptions, the only remaining relevant consideration is that traditional incentives deliver tax relief directly to the firm and customer-based incentives deliver tax relief to the firm’s customers.

1. Targeted economic development incentives and social welfare.

Can targeted economic development incentives increase or decrease the deadweight loss associated with the taxes they relieve?164 Can they affect the distribution of social welfare? If the answer to either question is “yes,” then policymakers should be careful when designing their tax provisions in order to most effectively achieve their goals. The answers to the above questions depend on a number of factors. The first factor is whether one of the parties is able to control who ultimately receives the tax relief provided by controlling post-incentive prices.165 As discussed earlier in the Article, it is assumed that a vendor receiving targeted economic development incentives will have this control.166 If the vendor controls prices, it could keep them at the pre-incentives level, capturing the full benefit of the tax relief.167

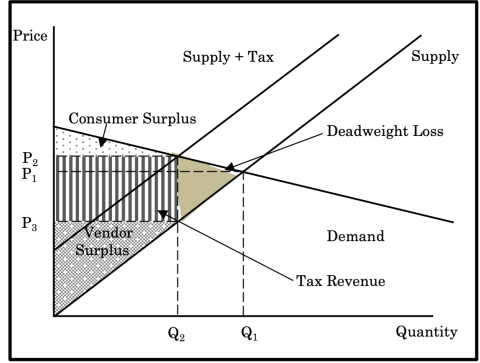

The second important factor is the elasticity of the supply and demand curves—how much supply and demand change in response to price changes. The more elastic a supply or demand curve is, the more extreme responses are; a small increase in price would significantly reduce demand and significantly increase supply for a highly elastic good.168 Elasticity matters in determining who bears the burden of a tax; the party with the more elastic response to price changes will bear less of the tax burden.169 Thus, if demand for a good is more elastic than supply, consumers bear less of the tax burden than vendors, as demonstrated graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Social Welfare with More Elastic Demand

Considering these two factors together, it becomes clear that targeted economic development incentives can—but will not always—affect social welfare. To reach this conclusion, it is important to recognize that tax relief provided through targeted economic incentives does not necessarily result in the elimination of the deadweight loss created by the taxes. Because the taxes are still levied generally, market prices should still reflect after-tax prices. Therefore, the firm can keep prices at after-tax prices, and the deadweight loss will remain.170 Because of this result, it may be helpful to think of tax relief as a refund of taxes rather than the elimination of taxes; for the taxes to be refunded, they must have been imposed in the first place.

Targeted economic development incentives will have no effect on the amount of social welfare if it is in the firm’s interest to keep prices at the after-tax, pre-incentives level (price P2 in the Figures); such incentives will increase social welfare if it is in the firm’s interest to reduce prices to the pretax level (price P1 in the Figures), sharing the relief with consumers and eliminating the deadweight loss from the tax.171 To see when these two results should be expected, a comparison of Figure 1 to Figure 2 is helpful. In either case, a firm receiving incentives will recapture the vendor surplus that had gone to the state as tax revenue;172 the important consideration is how much consumer surplus is available in comparison to the additional vendor surplus the firm could generate by eliminating the deadweight loss. Keeping prices at the pre-incentives level P2 allows the firm to capture the consumer surplus that had previously gone to the state as tax revenue; lowering prices to the pretax equilibrium level P1 allows the firm to generate additional social welfare (and thus vendor surplus) by eliminating deadweight loss, though the firm will not capture any consumer surplus. In Figure 1, the consumer surplus going to the state is greater than the vendor surplus eliminated by the deadweight loss (the lower portion of the deadweight loss triangle); thus the firm should prefer to keep the pre-incentives price and capture the consumer surplus that had gone to the state as tax revenue. The deadweight loss will remain. However, Figure 2 demonstrates that as the elasticity of demand increases, the amount of vendor surplus eliminated by the deadweight loss grows and the amount of consumer surplus going to the state decreases. At some point, the amount of eliminated vendor surplus will exceed the amount of consumer surplus captured by the state, and the firm will prefer to return to the pretax price P1, eliminating the deadweight loss and increasing the amount of social welfare.

Targeted economic development incentives can also affect the distribution of social welfare. When a firm captures all of the tax relief, there is a redistribution of welfare from consumers to the firm (that is, the firm captures the consumer surplus that had previously gone to the state as tax revenue). Whether this distribution is progressive, proportional, or regressive will depend on the status of the consumers and how the welfare is distributed by the firm. As a firm is not an individual, the social welfare it captures will ultimately fall to others, such as owners of the firm (through increased valuation of the firm), workers at the firm (through increased compensation), or customers of the firm (through lower prices).173 If the firm does not capture the tax relief, but instead eliminates the deadweight loss from the original tax, the distribution of social welfare returns to the pretax balance. Again, the progressivity, proportionality, or regressivity of this distribution will depend on the status of the consumers and how the vendor surplus is distributed by the firm.

Because the discussion has so far assumed that the firm and consumers are economically rational actors with full awareness of the incentives provided, there is nothing to indicate that customer-based incentives and traditional incentives affect social welfare differently due to their different forms. This result is unsurprising. Recall that numerous theories have demonstrated that the initial distribution of rights among parties should not matter in a rational-actor model; the parties will transact with each other to reach their preferred balance of rights.174 The form of targeted economic development incentives should not matter under the same assumptions. However, relaxing these assumptions exposes how the different forms can be expected to have different effects on social welfare.

2. Customer-based incentives’ ability to increase social welfare.

This Section argues that customer-based incentives are more likely than traditional incentives to increase social welfare, both by eliminating deadweight loss and by increasing consumer surplus. These results arise from the restrictions consumer biases place on firms’ ability to control prices and potentially from the hypersalience to consumers of the tax relief customer-based incentives offer.

As discussed, maintaining after-tax prices after receiving customer-based incentives may trigger fairness concerns or loss aversion in consumers.175 These results inhibit a firm from altering its pricing so as to capture the tax relief customer-based incentives offer.176 Such concerns and the resulting inhibitions are not present in the case of traditional incentives.177 Thus, the tax relief from customer-based incentives is more likely than that from traditional incentives to be shared with the firm’s customers; external factors pressure the firm into doing so. As the prior Section detailed, when consumers retain the tax relief, it is as though the taxes were never imposed—deadweight loss is eliminated, and social welfare is generated. Therefore, the state should have some preference for customer-based incentives over traditional incentives.

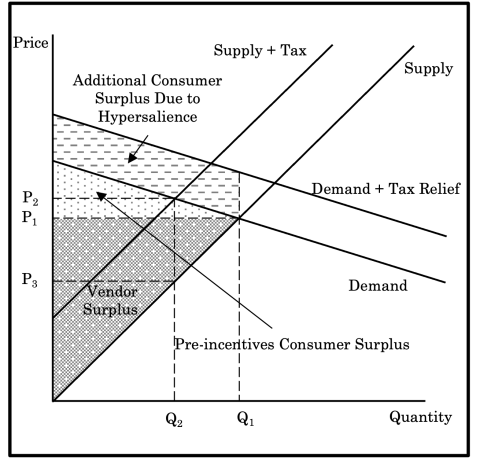

Additionally, that consumers can, and are likely to, find the tax relief provided by customer-based incentives hypersalient may cause customer-based incentives to generate more social welfare than traditional incentives.178 When the tax relief is hypersalient, consumers derive more satisfaction from purchasing from the firm than from other vendors, so the demand curve shifts up.179 This shift in demand (which does not occur in the case of the fully market-salient tax relief from traditional incentives) generates additional consumer surplus, and thus additional social welfare.180 In other words, a smaller amount of customer-based incentives can achieve the same result as a larger amount of traditional incentives because customer-based incentives cost the state less. Figure 3 demonstrates this effect by building on Figure 2, which shows a situation in which the firm would elect to return prices to the pretax equilibrium point. However, the potential for increased social welfare as a result of the hypersalience of the tax relief from customer-based incentives relies heavily on the assumption that traditional incentives and customer-based incentives would burden the recipient’s competitors in the same amount.181 If customer-based incentives result in more harm to the recipient’s competitors than traditional incentives (as might happen if customer-based incentives affect the relative demand for the recipient’s products more than traditional incentives), the net effect on social welfare of customer-based incentives may be less positive.

Figure 3. Social Welfare with Hypersalient Customer-Based Incentives

Even so, this Section has presented a number of reasons to suspect that customer-based incentives can generate more social welfare than traditional incentives. Thus, the use of customer-based incentives should not be dismissed out-of-hand on social-welfare grounds. So long as customer-based incentives have a better upside than traditional incentives in this regard, customer-based incentives should be appealing to states seeking to improve net social welfare. However, the overall effects on social welfare of any targeted economic development incentive will ultimately depend on a large number of factors of which the form of the incentive is only one. For instance, though this analysis has assumed such factors away,182 providing customer-based incentives to certain concentrated industries may prove particularly harmful to overall social welfare, as increased demand for one firm permits it to push its competitors out of business. A state seeking to improve net social welfare must balance the impact of the choice of firm with the impact of other such factors.

The following sections take a closer look at two such factors—the “escape issue” and the “civic virtue issue”. These are examined because they are commonly raised issues regarding the fairness of traditional incentives. People may derive more satisfaction, thus generating more social welfare, if the form of incentive selected better addresses these issues than the other does. In other words, people may be more satisfied when the form of tax provision selected is viewed as more equitable than other forms. The following discussion further demonstrates that the two forms can have different substantive effects and suggests that there are strong reasons to suspect that customer-based incentives will be considered more equitable than traditional incentives, improving their appeal.

B. The Escape Issue

Some critics of traditional incentives argue that the design of traditional incentives allows the firm to use the tax relief provided to finance activities in other states or to leave the state before fulfilling its obligations, causing the benefits of the incentives to “escape” the state in a way that is unfair to the state’s residents.183 In a sense, the firm using the tax relief to finance outside activities is merely a bargaining issue; the state should have required the firm to do more in the state for the incentives if it expected more. Money is fungible, and the fact that a firm uses tax relief to finance activities elsewhere does not mean that the firm did not fund its activities in the state. However, if a firm leaves the state before fulfilling its obligations, then the escape problem becomes more legitimate. In any event, a state’s citizens may not be comfortable with the possibility that any state-provided tax relief escapes the state.

As a basic response to the escape issue, many states have added various clawback provisions to their traditional incentives offerings which require the firm to return some portion of the incentives if it fails to meet its obligations.184 However, clawback provisions are rife with issues and have proven somewhat ineffective.185 As a primary matter, including the provisions decreases the value of the tax relief to the firm due to the risk that the firm may have to pay back some of the relief in the future, so more tax relief may have to be provided.186 Additionally, legal disputes can arise over whether the provisions apply when a firm leaves the state, creating costs for both parties and decreasing the likelihood that the state would be made whole even if it were entitled to be.187 Further, states may be reluctant to include or enforce clawback provisions because of the message doing so would send to other firms it hopes to lure in the future. One of the justifications for offering targeted economic development incentives is to show how business-friendly the state is; cutting against that display may be harmful to the state’s economic development goals.188

Customer-based incentives are less likely than traditional incentives to suffer from the escape issue, and thus do not need the support of awkward clawback provisions. The tax relief provided through customer-based incentives is directly tied to in-state activities, and to the extent that the relief is passed through to customers (as the above analysis indicates is likely), the relief is less likely to escape the state because individual consumers are likely to be less mobile than firms. To the extent the tax relief is captured by the firm, there may be larger escape concerns; however, because their tax relief is tied to in-state consumption, customer-based incentives discourage the firm from ceasing to engage in economic activity in the state. Finally, because the tax relief from customer-based incentives is spread out over time (due to the nature of sales and use taxes), the firm receives no lump-sum relief as it might through traditional incentives, mitigating the possibility of a misalignment in favor of the firm between what the state has paid out and the investments the firm has made in the state. If anything, the state is paying later for investments now when it provides customer-based incentives, so there is little risk of those payments financing activities outside of the state. Therefore, customer-based incentives appear far more capable of addressing the escape issue than traditional incentives and may be preferred by members of the public for that reason.

C. Civic Virtue: The Nonenforcement Issue