Democracy’s Deficits

Barely a quarter century after the collapse of the Soviet empire, democracy has entered an intense period of public scrutiny. The election of President Donald Trump and the Brexit vote are dramatic moments in a populist uprising against the postwar political consensus of liberal rule. But they are also signposts in a process long in the making, yet perhaps not fully appreciated until the intense electoral upheavals of recent years. The current moment is defined by distrust of the institutional order of democracy and, more fundamentally, of the idea that there is a tomorrow and that the losers of today may unseat the victors in a new round of electoral challenge. At issue across the nuances of the national settings is a deep challenge to the core claim of democracy to be the superior form of political organization of civilized peoples.

The current democratic malaise is rooted not so much in the outcome of any particular election but in four central institutional challenges, each one a compromise of how democracy was consolidated over the past few centuries. The four are: first, the accelerated decline of political parties and other institutional forms of popular engagement; second, the paralysis of the legislative branches; third, the loss of a sense of social cohesion; and fourth, the decline in state competence. While there are no doubt other candidates for inducing anxiety over the state of democracy, these four have a particular salience in theories of democratic superiority that make their decline or loss a matter of grave concern. Among the great defenses of democracy stand the claims that democracies offer the superior form of participation, of deliberation, of solidarity, and of the capacity to get the job done. We need not arbitrate among the theories of participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, solidaristic democracy, or epistemic democratic superiority. Rather, we should note with concern that each of these theories states a claim for the advantages of democracy, and each faces worrisome disrepair.

Introduction

History confounds certainty. Barely a quarter century after the collapse of the Soviet empire, it is democracy that has entered an intense period of public scrutiny. The election of President Donald Trump and the Brexit vote are dramatic moments in a populist uprising against the postwar political consensus of liberal rule. But they are also signposts in a process long in the making, yet perhaps not fully appreciated until the intense electoral upheavals of recent years. A percentage or two change in the Brexit vote, or a few tens of thousands of votes cast differently in a few key US states, would certainly have postponed the confrontation but would not have altered the fundamental concerns. With the realignment of the Dutch and French elections, the emergence of a hard-right populism in Hungary and Poland, and the mushrooming of antigovernance alliances in Italy and Spain, deeper questions must be asked about the state of democracy. Italy may have had forty-four governments in a fifty-year span, but power generally rotated among a familiar array of parties, personalities, and policies—until former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi reoriented politics and the current nihilist trends emerged.

Today’s moment is defined by the distrust of two key features of democratic governance: the centrality of institutional order and the commitment to what in game theory would be termed “repeat play,” the idea that there is a tomorrow and that the losers of today may unseat the victors in a new round of electoral challenge. The central idea of contestation, of losers and winners engaged in common enterprise, is ceding to what Professor Jan-Werner Müller refers to as a “permanent campaign”1 aiming to “prepare the people for nothing less than what is conjured up as a kind of apocalyptic confrontation.”2 In rejection of any pluralist account of democracy, “[t]here can be no populism . . . without someone speaking in the name of the people as a whole.”3 Populist impulses shorten the time frame and turn everything into a binary choice, a political life at the knife’s edge. Us or them, success or perfidy, the people or the oligarchs, Americans or foreigners. There can be no spirit of partial victory, of legitimate disagreement, or even of mutual gain through engagement.

At issue across the nuances of the national settings is a deep challenge to the core claim of democracy to be the superior form of political organization of civilized peoples. It is odd, and highly dispiriting, to have to engage this question so soon after democracy seemed ascendant as never before. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and its empire, the twentieth century concluded with democracy having defeated its two great authoritarian rivals, and the popular election of governments spread across a greater swath of the earth than ever before. The imprecise contours of ascendant democracy included generally robust markets, welfarist protections for citizens, a broad commitment to secularism (even in countries with an established church), and liberal tolerance of dissent and rival political organizations. All of this was packaged in robust constitutional protections of civil liberties and the integrity of the political order. Francis Fukuyama’s embellished claim that the end of history was upon us4 accurately captured the sense that electoral democracy alone seemed to lay claim to political legitimacy.5 Further, the opening to democracy invited economic liberalization, and the resulting market exchanges were allowing huge masses to rise from poverty, even in holdout autocratic states like China or Vietnam.

Clearly the era of democratic euphoria has ended. The rise of Islamic terrorism and the failure of the Arab Spring were certainly warning shots, but grave as these might be, they did not challenge the core of democratic government. The inevitable trade-off between security and liberty that accompanies external threats to democratic regimes is a serious challenge and can itself compromise core legitimacy. But democracies that withstood what Professor Philip Bobbitt terms the “long war” of the twentieth century6 were unlikely to come undone in the face of enemies who sought to target civilians but were in no position to pose a sustained military threat of any kind. Even the problematic military engagements in Afghanistan or Iraq bitterly divided democratic societies but did not threaten an epochal confrontation with democracy itself.

Instead, the current moment of democratic uncertainty draws from four central institutional challenges, each one a compromise of how democracy was consolidated over the past few centuries. The four I wish to address are: first, the accelerated decline of political parties and other institutional forms of popular engagement; second, the paralysis of the legislative branches; third, the loss of a sense of social cohesion; and fourth, the decline in state competence. While there are no doubt other candidates for inducing anxiety over the state of democracy, these four have a particular salience in theories of democratic superiority that make their decline or loss a matter of grave concern. Among the great defenses of democracy stand the claims that democracies offer the superior form of participation, of deliberation, of solidarity, and of the capacity to get the job done. We need not arbitrate among the theories of participatory democracy, deliberative democracy, solidaristic democracy, or epistemic democratic superiority. Rather, we should note with concern that each of these theories states a claim for the advantages of democracy, and each faces worrisome disrepair.

I. Participation: Failing Political Parties

[P]olitical parties created democracy and [ ] modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties.

—E.E. Schattschneider7

[P]arties [are] the distinctive, defining voluntary associations of representative democracy.

—Nancy L. Rosenblum8

One indicator of the age of the American Constitution is the absence of any role for political parties, by contrast to Article 21 of the German Constitution, for example.9 The Framers of the US Constitution equated parties with factions, and aimed for a form of democratic politics that would rise above sectional concerns, immediate gratification of wants, and the risk of succumbing to the passions of greed and envy. But as early as the first contested presidential election in 1796, the Founding generation discovered the need to coordinate national candidacies in furtherance of a political program. They quickly formed the very factions they had sought to avoid, now organized as incipient political parties. Even in the Founding era, partisan actors learned that they could not mobilize the rather inert mass of the population into a national campaign without coordination of resources, messages, and programmatic commitments for governing. Each of these undertakings required not only the right of citizens to participate electorally in self-governance, but the creation of intermediary institutions that could mobilize citizens into partisans.

Not until the twentieth century were political parties granted constitutional recognition as part of the fabric of democratic politics—indeed, the first nineteenth-century constitution that addressed the status of political parties was that of Colombia in 1886, and there in order to ban parties. By contrast, the constitutions of the twentieth century privileged political parties as the galvanizing force of democratic politics.10

As experience in electoral self-government grew, democrats throughout the world learned that parties provide a forum for the integration of the different interests that must coalesce for successful policymaking, more so in first-past-the-post elections than in proportional representation systems. Even in parliamentary systems, some form of aggregation is necessary to draw sufficient attention to the party platform and to make the party a desirable suitor in forming a governing coalition. But mostly parties were the institutional mechanism for translating interests and ideology into governance. Politics is the art of the possible, even if what is possible and necessary at any particular moment fails to inspire. Without parties, responsible and productive governance rested on the happenstance of enlightened leaders rather than an institutionalized mechanism for taking hard decisions, cutting deals, accepting short-term costs for longer-term gain, and all the mechanisms that define wise stewardship.

In the United States, parties served as the political expression of the spirit of voluntary associations critical to the young Republic. As Alexis de Tocqueville noted, “Americans of all ages, all conditions, and all dispositions, constantly form associations. . . . Wherever, at the head of some new undertaking, you see the government in France, or a man of rank in England, in the United States you will be sure to find an association.”11 By the time Tocqueville came to America, political parties were emerging as among the most salient of these associations. As they matured through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, parties provided the organizational resources for political campaigns, selected candidates, coordinated platforms, and disseminated information about politics.12 In exchange, parties dispensed patronage and access to power, the glue that held the activist wings of the party in check and that allowed a coordinating discipline to be imposed on the party’s elected representatives.13 As I have written elsewhere, the organizational fabric of parties came undone in the United States in the late twentieth century, partially as a result of legal reforms that left significant aspects of party governance outside the control of party leaders,14 and partially through external factors, such as the rise of low-cost social media and the mechanisms of direct access to funding and the party constituency.15

Examined globally, the American experience of tottering political parties appears emblematic rather than exceptional. The result in country after country is the dissolution of the discipline of political parties in favor of a politics of free agency formed largely around the personae of individuals or momentary issues, devoid of a sustaining institutional presence. In the American context, Professor Richard Pildes describes this central feature of contemporary politics as the process of political fragmentation: “[T]he external diffusion of political power away from the political parties as a whole and the internal diffusion of power away from the party leadership to individual party members and officeholders.”16

But the breaking up of central institutions extends far beyond the domain of politics—the economic conglomerates of yesteryear, such as ITT and Gulf & Western, were long since dismantled in favor of independent specialized units.17 In the political domain, fragmentation is a fact of life in all democratic countries, meaning that attempts to find the causal roots at the national level will necessarily be incomplete. The process of what is termed “fissuring” in labor economics18 reflects the broad destabilization of large integrated organizations in the face of technological change, ease of communication, globalization, and other pressures on previous advantages of scale. Whether across supply markets or in the domain of politics, ease of communication and transportation puts pressure on broad horizontal organizations whose prime advantage was access to markets, economic or political. In Coasean terms, it becomes less administratively burdensome to buy rather than make, and firms can become a purer form of their particularized specialization.

The same is true in the political domain, in which access to voters and donors is no longer coordinated through the large umbrella of the political parties. Populists eschew political parties and social media allows direct appeals for both money and support.19 Part of the ability of populists to bypass established party structures is no doubt the failure of the political parties to adapt to the modern era. But the cumulative result is the decline of the parties as the locus of democratic politics and the rise of the individual-centered definition of politics. As parties fragment, a spiral ensues. Targeting specific groups of voters, activists, and donors requires more focused and generally more extreme messages. Broad-tent parties become an impediment to a new form of politics that channels passion rather than rewarding the necessarily limited returns from governance. More broadly, the disengagement from the parties leads to what Professor Emanuel Towfigh terms the “party paradox,” in which parties, though necessary to democratic functioning, become a contributing source of disenchantment with the political process: “This paradox of representation may reduce the acceptance of political decisions by the electorate and contribute to the overall disillusion with democracy.”20 The result, well captured by Professor Peter Mair in his work on “hollowed out” European democracies, is that politics “has become part of an external world which people view from outside,” as opposed to the old world in which they participated.21

Weakened political parties do not have the institutional fortitude to withstand hostile challenges from outsiders, as evident in the United States, where President Trump and Senator Bernie Sanders (the former a marginal affiliate of the Republicans, the latter not even a member of the Democratic Party) were able to displace established party figures, and in the case of Trump, walk away with the party endorsement and ultimately the presidency. In place of programs and governance, candidacies are now centered on individuals and elections are framed as referenda on the leadership of those individuals. Even in Germany, the country that has best resisted the assault on democratic institutions, there is a noted increase in the personalization of the campaigns of Chancellor Angela Merkel.22 Candidate-driven elections are increasingly the norm in Europe as parties that emerged from the capacity to gain parliamentary representation are no longer needed as an electoral platform.23 Even the desultory elections for the European Parliament witnessed an effort to attract personalities to the candidate roster in a vain attempt to boost voter turnout.24 Direct candidate appeal to voters goes hand in hand with the documented fragmentation of political parties in, among other places, Bolivia, Bulgaria, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, France, Guatemala, India, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, and Thailand.25 Mair summarizes this well:

Parties are failing, in other words, as a result of a process of mutual withdrawal or abandonment, whereby citizens retreat into private life or into more specialized and often ad hoc forms of representation, while the party leaderships retreat into the institutions, drawing their terms of reference ever more readily from their roles as governors or public-office holders.26

In this sense, the desperate gambit of Prime Minister David Cameron to seek to solidify his political base by appealing to plebiscitary alternatives to parliament emerges from the failure of political discipline in the legislative setting.27 It well follows the pattern in the European Union of seeking to alter its perceived democratic deficit through greater use of referenda and other tools of direct democracy.28 Put less delicately, Nigel Farage, the leader of the UK Independence Party (UKIP), touted the Brexit vote as the story of the British people telling the political elite to stick it: “It is, after all, rather extraordinary that more than half the voting population defied a large majority of its own elected parliament, all of the traditional political parties, and virtually every important institution in the country—from the Central Bank to the leaders of industry to the trade unions.”29 Nor did the Brexit fiasco prevent embattled Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi from turning to a constitutional referendum to shore up his government in 2016, with the same disastrous results.30 The immediate need to seek political ballast through a plebiscite may reflect the momentary political crises in Britain or Italy. But the allure of referenda reflects the disenchantment with political parties, and the desperate effort to restore governing authority simply confirms the weakness of parliaments as authoritative institutions. Rather than offering a lifeline to government, these referenda are a desperate gambit reflecting the problems that gave rise to Brexit in the first place: “[T]ensions have grown in most Western nations between the existing processes of representative democracy and calls by reformists for a more participatory style of democratic government.”31

If Brexit highlights the perceived weakness of political parties as coordinators of democratic politics, it raises the question of the root cause of that weakness. In substantial part, the weakness follows from the simple fact that the parties cannot claim to speak for much of a constituency. In other words, they have significantly lost their participatory quality. To give but one example, in 1950, 20 percent of Britons were members of political parties; as of 2014, that figure was about 1 percent.32 In the United States, according to the Pew Research Center’s yearly studies of American political behavior, party identification is at an observed all-time low. Currently, 39 percent of Americans identify as independents, 32 percent as Democrats, and 23 percent as Republicans: “This is the highest percentage of independents in more than 75 years of public opinion polling.”33

Party failures are intrinsically connected to the demise of the institutional supports of those parties. Throughout the twentieth century, parties relied heavily on other forms of organization to provide their active constituency. For the Democratic Party in the United States, for the Labour Party in Britain, and for the social-democratic parties of Western Europe, that organizational backing came heavily from the labor unions.34 For the Republicans in the United States and the Tories in Britain, and the Christian democrats and conservative parties in Europe, the organizational ties were to the chambers of commerce or other locally based representatives of small businesses and agricultural interests.35

Taking the United States as an example, the decline of underlying institutions is as precipitous as the decline of parties. Union density today is at an all-time low since the New Deal created federally mandated rights of collective bargaining. Union decline captures only a part of the picture. Significant as well is the shift in composition of the unionized workforce reflected in the domination of unionization in the public sector. While about 11 percent of the American workforce is unionized, the figure for the private sector has fallen below 7 percent, while public sector unionization remains at about 35 percent.36 Not only have unions declined outright, but perhaps more significantly, they have ceased to be an independent source of support for political parties outside the state realm. To the extent that unions centrally become the expression of public employees, they no longer organize a constituency independent of the political realm. Instead, labor unions are largely an expression of the political party to which they are affiliated, and become another political actor whose fortunes are tied to that party’s electoral capabilities.37 Not surprisingly, efforts to consolidate Republican political power at the state level, as exemplified by Governor Scott Walker in Wisconsin, seek to undermine the power of public-sector unions as a proxy for the Democratic Party. These are not battles reflective of participatory engagement by diverse sectors of the society, but power struggles within the state itself.

On the other side of the ledger, we find a corresponding erosion of broadscale institutional engagement. In the United States the best example comes from the evolution of the Chamber of Commerce from the organizational representative of local enterprise to the exponent of the interests of concentrated capital: “Mention the Chamber of Commerce, and most people think of a benign organization comprised mostly of small business owners who meet for networking and mutual support in local chapters across the U.S. But today’s Chamber is anything but that.”38 The Chamber’s interests are now highly focused around a small number of industries and interests, including “tobacco, banking, and fossil fuels.”39 According to one article, 64 donors were responsible for more than 50 percent of all donations to the Chamber, while 94 percent of its donations came from a pool of just 1,500 top donors.40

Across the political spectrum, parties become tied not to broad-based constituency organizations, but to much narrower sectional interests, already well entrenched in the corridors of power. The claim of parties as a special arena of participatory engagement in the democratic project wanes accordingly. The parties emerge hollowed out, just as do their organizational bases of support.

II. Deliberation: The Weakness of Legislative Branches

[Deliberative] collective decision-making ought to be different from bargaining, contracting and other market-type interactions, both in its explicit attention to considerations of the common advantage and in the ways that that attention helps to form the aims of the participants.

—Joshua Cohen41

[T]he democratic method is that institutional arrangement for arriving at political decisions which realizes the common good by making the people itself decide issues through the election of individuals who are to assemble in order to carry out its will.

—Joseph A. Schumpeter42

Rarely would Professor Joshua Cohen and Joseph Schumpeter be lumped together in theories of democratic legitimacy. Yet they both look to a discursive element to raise the capacity of democratic governance to reach the common good, and to reach beyond mere sectional claims on spoils. For Cohen and the more classic deliberativist tradition, the domain of discourse is in public participation and direct engagement.43 For Schumpeter and those in his tradition, myself included, elite competition in the electoral arena provides the foundations for citizen engagement and education, and the ensuing retrospective accountability for the exercise of governmental power.44

Under either view, democratic political theory justly emphasizes the educational gains of deliberation in an engaged citizenry.45 Even when citizens in modern democracies govern through representatives rather than as a collective body, periodic elections guarantee that citizens encounter political arguments that may be removed from their everyday lives.46 Elections compel deliberation among the citizenry as candidates and parties attempt to sway and educate. That deliberation then translates into the legislative arena as elected officials seek to translate campaign promises into governing policies.

For present purposes, we limit our discussion to the institutionalization of deliberation in the legislative arena rather than in the lived experiences of the citizenry. Democracies are conceived around legislative power, from Magna Carta’s parliamentary check on the Crown, to the expansive role of Congress defined by Article I of the Constitution, to the revolutionary emergence of parliamentary power throughout the nineteenth century. Colloquially, Americans once spoke of the Senate as the “world’s greatest deliberative body.”47 It is no overstatement to say that this is the world’s ennobling democratic inheritance. Or, put another way, the hallmark moments of twentieth-century authoritarian rule are intertwined with the rejection of parliamentary deliberation and with compromise in favor of the plebiscitary triumphs of a Hitler or Mussolini.48

The legislative arena, at least in theory, is the clearest institutionalized setting for democratic deliberation. In its classic rendition, it is the arena in which “participants of deliberation, before counting votes, are open to transform their preferences in the light of well-articulated and persuasive arguments.”49 On this view, the process of deliberation transforms democratic politics because it “requires the participants to display the reasons why they support a particular stand. It comprehends an exercise of mutual justification that allows a thorough type of dialogue before a collective decision is taken.”50

Yet, in the modern era, the words “Congress” and “dysfunction” seem to go together like a horse and carriage, with some apology to Frank Sinatra. Consider that the total enacted legislation annually by the US Congress has declined considerably from the 1970s, in which as many as 804 bills were passed, to the most recently finished Congress, in which only 329 bills were passed.51 But focusing on the United States misses much of the picture. Across a number of markers, the legislative branches of mature democracies have declined as centers of policy debate and formation. In their place, executives have adopted more muscular policymaking roles, checked primarily by courts.

This is a large topic to which I have devoted an entire monograph.52 But for the current presentation, consider just one partial indicator of the trend over time in the United States. Since President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fabled first hundred days in office ushered in the transformative New Deal, presidents have routinely devoted themselves to hitting the ground running, using the initial period of pride among the partisans and disorganization among the vanquished to show muscular leadership. The effort to blaze through the first hundred days has not changed, but the form has. The number of legislative initiatives of the first hundred days has dropped steadily, from seventy-six new statutes under Roosevelt, to seven and fourteen under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, respectively.53 Even though, of course, presidents do not pass legislation, and even though they might often confront a Congress or a chamber with an opposition majority, the drop-off does not mean presidential inaction. While legislation has dropped, executive decrees have increased throughout the modern period. Consistent with this trend, President Trump had no significant legislative activity at all during his first hundred days in office, and the number of substantial legislative initiatives amounted to zero.54

The failure of the participatory side of democratic politics ties directly to the difficulties encountered on the deliberative side. Parliamentary democracies are centered on the parties. Candidates run as part of a slate, and the demand for a larger share of seats in parliament is what offers the prospect of national stewardship. In theory, there are so many competing interests, and such inconsistency in potential political outcomes depending on who has control of setting the agenda and deciding what is presented in what form, that there is a risk of complete incoherence in the legislative process.55 The cycling-of-preferences problem, the great insight of Professor Kenneth Arrow and the ensuing study of public-choice theory, threatens to collapse the capacity of any legislative body charged with policy leadership.56 The need for coordination is apparent, with the Supreme Court long ago observing that parties emerged “so as to coordinate efforts to secure needed legislation and oppose that deemed undesirable.”57

The result of parliamentary dysfunction is correspondingly rising executive unilateralism,58 the increased dependence on administrative law to set policy, and the central checking role of the courts as restraints on presidentialism—even in formally parliamentary systems. Doctrinally, the absence of congressional action not only removes the central democratic branch from the reins of government, but also makes judicial constraint more difficult. Following Justice Robert Jackson’s famous Steel Seizure typology, the power of the executive is at its “lowest ebb” when the president seeks to countermand the actions of Congress.59 The unstated flip side of Jackson’s observation is that the pathway for judicial repudiation of executive action is correspondingly easier when Congress has blazed the trail. When Congress fails to act, the mechanisms of democratic constraint are compromised.

For Jackson, congressional inaction posed the most difficult issues for democratic governance and, by extension, for the judiciary. As he framed the problem:

When the President acts in absence of either a congressional grant or denial of authority, he can only rely upon his own independent powers, but there is a zone of twilight in which he and Congress may have concurrent authority, or in which its distribution is uncertain. Therefore, congressional inertia, indifference or quiescence may sometimes, at least as a practical matter, enable, if not invite, measures on independent presidential responsibility. In this area, any actual test of power is likely to depend on the imperatives of events and contemporary imponderables rather than on abstract theories of law.60

In the absence of legislative initiative, executive power naturally rushes to fill the void, whether through governance by direct decree or by indirect administrative command. Without the legislative branch offsetting the powers of the executive, the job of defining the boundaries of prerogative power and regulatory authority falls to the judiciary. As Jackson cautioned, the lines of judicial engagement are least clear—the “zone of twilight”61 —when there is institutional failure in the legislature, and the “least dangerous branch” finds itself at risk of open conflict with the executive.62

There is nothing distinctly American about hypertrophic executive power in the modern era. Even before the UK Supreme Court had to engage the authority of the prime minister to implement Brexit, a topic to which I shall return in concluding,63 the British government confronted the military consequences of executive unilateralism in the disastrous Iraqi campaign.64 One proposal, from the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution, would have implemented limitations similar to those of the American War Powers Act,65 obligating parliamentary approval for any long-term military engagement.66 As future Prime Minister Gordon Brown observed at the time, “Now that there has been a vote on these issues so clearly and in such controversial circumstances, I think it is unlikely that except in the most exceptional circumstances a government would choose not to have a vote in Parliament [before deploying troops].”67 The lack of accountability and the absence of parliamentary engagement was confirmed by the 2016 Chilcot Report, whose many condemnations of Prime Minister Tony Blair included criticism of unilateral decisionmaking by the executive.68

It is not possible in this one exposition to engage the extensive discussions at the level of national democracies on parliamentary failure to check the executive. A review of the literature shows a persistent theme among both academic commentators and pundits to be the collapse of responsible government at the parliamentary level.69 The causes for that collapse identified in the academic literature include concerns about thresholds of representation, party fragmentation, increasing presidentialism and semipresidentialism, and the displacement of parliamentary authority by international accords or, in the case of Europe, the overreach of Brussels.70 Pundits are more inclined to point to the venality or corruption of parliamentary officials, though in some countries, such as Brazil, the two come together.71

Parliamentary democracies are centered on the parties. Candidates run as part of a slate and the demand for a larger share of seats in parliament is what offers the prospect of national stewardship. The collapse of parliaments compounds the consequences of the collapse of parties, and the two are both the cause and effect of each other. Invariably, the locus of political activity shifts to the executive, and the defining feature of democratic politics turns to the triumphalist claims of the victorious head of state. Consider this account of contemporary politics:

What we are seeing in the presidential campaigns . . . is that the more chance the candidates have of winning—or the more chance they think they have of winning—the more they are prepared to play the game that I call “national presidentialism.” They go in for speeches that amount to saying: “If I’m elected, then everything . . . is going to be different because I’m the only one able to lead this country.” . . . All that matters is how the candidate is going to be able to restore [the nation’s] image once he or she has been given supreme power.72

This account of contemporary politics would ring true in many democracies around the world, the United States clearly included. In my native Argentina, such “caudillo politics”73 has generally been the mark of the demise of democracy rather than its fulfillment. That this particular statement happens to be about France and that the speaker is Daniel Cohn-Bendit, the leader of the 1968 student uprising, only makes it a bit more piquant.74

III. Solidarity: The Threats to Social Cohesion

A central theme of my work on Fragile Democracies concerns the inherent difficulty in democratic governance in the absence of a democratic polity. Strikingly, and perhaps paradoxically, elections are seen in post–World War II state formation as the means toward the creation of a democratic state rather than a system of choice among those already committed to a common enterprise of collective governance.75 In countries emerging from colonial rule or despotic regimes, elections were the confirmation of a democratic transformation, even as they often served as the marker of who would hold state authority in a world of unfinished “us-versus-them” business.76 Our era of diversity may applaud the benefits of such broad democratic aspirations, but citizens of Burundi or Bosnia-Herzegovina or Iraq would well understand the frailties of democracy without a solidaristic commitment to a collective future.

The role of communitarian solidarity suffers from the traumas of the twentieth century, from Nazism to the ethnic slaughter in the Balkans. One reads back with horror at Carl Schmitt proclaiming that “[d]emocracy requires [ ] first homogeneity and second . . . elimination or eradication of heterogeneity.”77 The unmistakable message is that “[a] democracy demonstrates its political power by knowing how to refuse or keep at bay something foreign and unequal that threatens its homogeneity.”78

Yet, a look back at our democratic inheritance shows how central earlier generations thought the sense of shared identity, and that the ties between social cohesion and self-government are not an invention of twentieth-century reaction. In the background of the Founding documents of constitutionalism in the United States is the claim, no doubt jarring from a slave society, that the American blessing of liberty could be traced to the conception of homogeneity of the population, a claim that hauntingly echoes in Schmitt. In the words of John Jay, in Federalist 2:

Providence has been pleased to give this one connected country, to one united people, a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion, attached to the same principles of government, very similar in their manners and customs, and who, by their joint counsels, arms and efforts, fighting side by side throughout a long and bloody war, have nobly established their general Liberty and Independence.79

Jay may today be the least celebrated of the authors of The Federalist Papers, but the sentiment was widely shared, with John Stuart Mill later extending the argument to make it not simply an observation about America but a prerequisite for democracy: “Free institutions are next to impossible in a country made up of different nationalities. Among a people without fellow-feeling, especially if they read and speak different languages, the united public opinion necessary to the working of representative government can not exist.”80

Liberal theorists, notably including John Rawls, continued into the twentieth century the tradition of making claims for just treatment of citizens turn, at least in part, on a shared sense of “political traditions and institutions of law, property, and class structure, with their sustaining religious and moral beliefs and underlying culture. It is these things that shape a society’s political will.”81 The arguments do not sound in the need for consanguinity so much as the continued importance of a sense of collective identity in order to sustain citizen self-government. Democratic politics has long provided a critical forum in which solidarity could blossom. Across democratic societies, political parties provided the organizational framework for sports leagues, adult education projects, and newspapers—all of which served as intermediaries between citizens and the broader society. These agencies of civil society are weakened and leave citizens increasingly disengaged from political life, as reflected in declining voter participation rates across the democratic world. The problem of a lack of collective identity is more acute at the higher levels of efforts at European governance being compromised by trying to craft a democracy without a demos.

Among the contemporary challenges in advanced democratic societies are significant erosions in the sense of collective solidarity that provided the historic glue for the common project of democratic governance. For immediate purposes, I focus on two: the challenge of immigration and the challenge of declining living standards of the broad mass of the population—the toilers and voters of democratic states. There are many manifestations of contemporary social dissolution. But the combination of economic insecurity and the presence of perceived outsiders seems invariably to lead to fear of the other as taking over and blame on the other for a corresponding loss in social standing and wealth. The point here is not the normative claim that this sense is or is not justified, or even the positive claim of a causal relation between immigration and economic malaise. Rather, the issue is the democratic challenge posed by widespread sentiments among the laboring classes of being under siege. There is not a populist movement in a western democracy at present that does not play to both xenophobia and economic insecurity. The immediate question is why these strains have such force at present, and why they seem to operate in tandem.

While the answers are no doubt complex, they must begin with an assessment of the empirical realities of modern democratic societies, still reeling from the financial meltdown of 2008. The brute fact is that there is a loss of cohesion that accompanies high periods of immigration until the new immigrants are integrated into the national consensus.82 What Americans celebrate as the melting pot is undoubtedly a process of change and recreation of the national identity, but provides for mechanisms of integration of waves of immigrant populations. Even in the best of circumstances, the process of integration and the corresponding accommodation of prior governing values will take time. What hopefully ends up a richer cultural environment (oftentimes with side improvements from food to music) invariably begins as a project of social and linguistic strain.

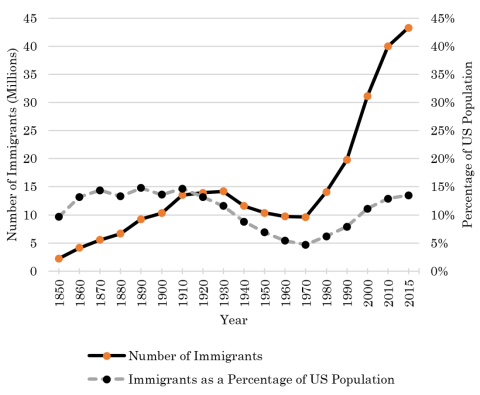

Taking the United States as the key example, Figure 1 shows that there is no escaping the fact that immigration has risen dramatically in the past quarter century and that the level of foreign-born Americans is at its highest in a century—precisely the time of the last great burst of nativist populism in the United States.

Figure 1. Number of Immigrants and Their Share of the Total US Population, 1850–201583

What is striking here, apart from any concerns about the distribution of immigrant labor skill levels, or even the number of legal versus illegal immigrants, is just the sheer number. The last immigration-fueled nativist turn transformed American politics for a generation, including closed-border constraints on immigration, isolationist politics, and even Prohibition directed at the drinking habits of recent immigrants.

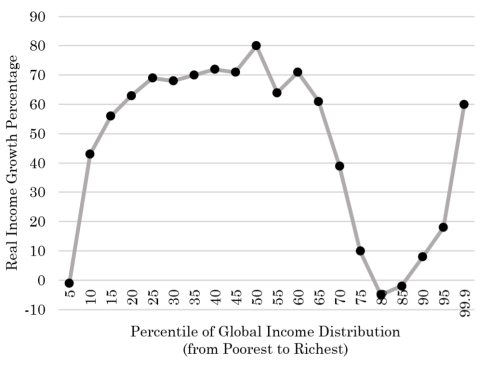

The challenge of immigration emerges politically in tandem with the sense of loss in the economic sphere. In what is referred to as the “elephant curve,” produced by the World Bank and reproduced in Figure 2 below, there is a graphic depiction of a global redirection of wealth over the twenty-year period leading into the financial meltdown, perhaps as significant as any ever recorded.84 The graph shows a stunning rise in the real incomes of the great majority of the world’s population, with huge numbers being lifted from poverty—primarily, though not exclusively, the result of the Chinese economic transformation.

Figure 2. Global Income Growth from 1988 to 200885

With the exception of the very poorest of the poor, the past thirty years have witnessed a transformation of lives around the world from extreme poverty to levels of income, health, material possessions, and life prospects that begin to challenge those of the advanced industrial democracies. The graph further reflects the rise of finance and the dominance of the top 1 percent, a subject of democratic challenge for some form of equitable redistribution. But the most important part of this chart is the downward curve at which real levels of income variously increased at significantly lower rates, stagnated, or even decreased over the same twenty-year period. This is the two deciles of the world’s population found at roughly the 65th to 85th percentiles of world income distribution. That group is roughly the working classes and lower middle classes of the advanced industrial countries that form the longest-standing core of democratic societies.

As a normative matter, redistribution from wealthier nations to poorer ones in a period of rising wealth must be applauded. The economic dislocations in the advanced industrial countries translate on the ground into hundreds and hundreds of millions of people being lifted from truly destitute conditions. But the global processes that have done much to alleviate human suffering do not dampen the consequences of the inability of the advanced societies to cushion the domestic effects of international migration and global economic integration or to redistribute internally from the winners to the losers of globalization.

The democratic sense of solidarity comes under siege as the laboring backbones of the advanced industrial countries find themselves challenged by a lost sense of recognizing their country amid rapidly changing demographics. It also comes as the rest of the world is exerting downward pressures on their living standards and as wealth shifts markedly to other parts of the world. As voters, these threatened groups in advanced societies were the backbone of the major parties of twentieth-century democracy—the labor and social-democratic parties on the left, and the Christian democratic and center parties on the right.

Both labor and the center-right parties were traditionally cautious to be negative on immigration and cross-border trade.86 While their policies differed, each saw a central part of its political role as protecting the always vulnerable working class and small entrepreneurial class, including the highly subsidized agricultural classes in countries like France, from economic dislocation. Both immigrants and the entry of cheaper goods from abroad threatened the less dynamic sectors of the advanced world economies. This is especially true for the working classes. Private-sector labor unions saw immigration as a source of downward pressure on wages and resisted it as such. By contrast, public-sector unions primarily attend to the level of government expenditures on employment and tend to be neither protectionist on trade nor cautious on immigration.87 When we look to the upper Midwest voting for President Trump, the decayed industrial north of England voting for Brexit, or the frayed industrial towns of northern France voting for the National Front, the message of governmental failure to provide for basic social security rings loudly. And, when coupled with the sense of the traditional institutions being disengaged from working class concerns, the field is left open to populist anger, whether from the right or left.

Indeed, the message resonates in those communities feeling left behind. One simple measure in the United States is to break down the vote by county, the basic unit of local governance. Trump won roughly five times as many counties as Hillary Clinton, but the counties that Clinton won included almost all the largest and most dynamic urban areas of the country—indeed, although a numerical minority, the counties won by Clinton generated 64 percent of the national gross domestic product.88 In Britain, the same pattern obtained in the Brexit vote. Leaving aside Scotland and the eastern precincts of Northern Ireland (where voters were probably more inclined to leave the United Kingdom than the European Union), the Brexit vote matched the economic prospects of the local populations. Brexit lost in London and the relatively prosperous South, and carried most of the rest of the country, save for a few areas of economic resurrection in Manchester and Liverpool.89 Put another way, Brexit was the dominant choice of those over forty, the generations that had felt declining wage prospects, but not the generation under forty.90 Comparable distributions could be found in the French presidential elections, as well.91

The groups threatened by declining economic prospects, a sense of isolation in their own countries, and the combined effects of foreign threat delivered Brexit and Trump’s victories in the upper Midwest. Now feeling vulnerable, these voters are increasingly deserting their former political affiliations in favor of angry populist reactions, frequently led by demagogic appeals to isolation and the sense of lost horizons. From Brexit to Italy’s Five Star Movement to Trump to the National Front to Spain’s Podemos, the trends are dramatic. The historic array of postwar political parties offered neither economic security nor a sense of political protection from outsiders, and were displaced by those much closer to the sense of populist dismay.

In particular, the financial crisis of 2008 appears to have been the defining blow that exposed the frailty of democracies. The sudden economic dislocation stressed the already weak political institutions of governance and the ability of traditional political parties to offer prospects of remediation.92 For the laboring classes of the advanced democracies, for whom the decades leading to 2008 had often offered a steady decline in relative real-wage growth, confidence in any remnant of the political status quo to cushion the further postcrisis economic decline was exceedingly low.93 Without functioning politics, democracies are ill prepared to offer security, redistribution, or optimism about life prospects for their citizens. That huge numbers of the populations of the democratic countries no longer trusted in the solidaristic commitment of the society or its capacity to protect them fueled the current populist backlash.

IV. Getting It Done

Democratically produced laws are legitimate and authoritative because they are produced by a procedure with a tendency to make correct decisions.

—David M. Estlund94

Over the past two centuries, democracies have outfought, out-innovated, and outproduced their rivals. With singular capacity, democracies raised the living standards of the broad masses of their populations, raised education levels to permit citizen engagement, and at the same time were able to trust powerful militaries to protect them from foreign assault without succumbing to military rule. History is obviously much more complicated and this is a somewhat tendentious reading, but it captures the ideological consensus that prevailed after the collapse of the Soviet empire and the brief era of presumed democratic universalism.

As Professor Branko Milanovic’s elephant curve chart on income distribution95 shows, however, the optimistic story is under serious challenge. The China/Singapore models96 of authoritarian rule coupled with high state competence highlight an emerging feature of democracies: the presence of multiple veto points blocking the creation of public goods and equitable policies. Mature democracies include mechanisms of transparency, due process, and participation that provide an entry point for private interests to block undesired governmental action.97 Under such circumstances, it is easier to block than to build and the result is to raise the costs of public endeavors dramatically. Fukuyama terms this the rise of “vetocracy,” defined as “a situation in which special interests can veto measures harmful to themselves, while collective action for the common good becomes exceedingly difficult to achieve. Vetocracy isn’t fatal to American democracy, but it does produce poor governance.”98 Easy confirmation can be found in the wobbly efforts of the Republicans in the US Congress to pass from a party of opposition to a party of governance on their signature demand for the repeal of the Affordable Care Act.99 After seven years of campaigning on a promise to repeal Obamacare, a clear Republican majority in the House of Representatives had trouble even proposing legislation to be submitted to a congressional vote.100

The central claim to superior competence of democracies is not the process of governance but the outputs that result; deliberation is necessarily slower and more complicated than decree. At some point, however, deliberation is not a process of citizen inputs but a public-choice nightmare in which vested sectional interests can marshal resources to overwhelm the passive majority. The result is a failure of public policy leadership and a collapse into rewards for privileged access to the strongest forces in government, almost invariably the executive. As I have described the process elsewhere, “the ‘three C’s’ of consolidated power take hold: clientelism, cronyism, and corruption.”101 The result is “weak democracies with autocratically minded leaders, who govern through informal, patronage networks . . . . [C]lientelism binds many citizens to ruling elites through cooptation and coercion.”102 Such failing democracies have no necessary organizational superiority to more decisive regimes, and indeed the presence of numerous veto points to action may actually make democracies less capable.

Consider an example from major new airport construction, a massively complex undertaking that has not even been attempted in the United States since the opening of the Denver airport in 1995. An international traveler to Beijing cannot help but be awed by the majestic beauty of the Terminal 3 international arrivals. Built for the opening of the Beijing Olympics, and designed by English architect Norman Foster, its dramatic arches evoke both the red lacquer motifs of Imperial China and the bird’s nest design of the Olympic stadium. The new terminal was constructed, from design to completion, in four years, a massive effort that included three work crews a day, laboring on rotating eight-hour shifts.103

By contrast, compare Terminal 3 with Heathrow’s Terminal 5 in London. Like Terminal 3 in Beijing, Heathrow’s Terminal 5 is designed by Norman Foster. Yet it is at best functional, a desperately needed additional space for an overcrowded airport. It has no grandeur, no inspiration, no sense of tribute to a rising power—and it took twenty years to complete.

When pressed about this in a BBC interview, Foster acknowledged the gains in completion time in China from more efficient labor use, lower regulatory demands, ease of siting, and a host of other factors. But even on Foster’s account, there were years of delay that could not be accounted for. Instead what emerges is the capacity of Chinese authorities to simply get the job done: “[Y]ou’ve taken out the democratic process, you’ve taken out the plan, so that comes down to decision making, it comes down to having a very, very clear idea of objectives and getting on with it.”104 At the end of the day, the capacity to produce turned on the difficulties of democracy, an observation that challenges democratic claims of superior capacity. Thus, Foster contrasts the British perspective—“[O]h well, it took a long time but we are a democratic society”—with the societal “hung[er] for change and [ ] for progress” driving rapid production in China.105

Of course, my home airport in New York is LaGuardia, which makes Terminal 5 look like paradise. Among New York’s signature contributions to democratic dysfunction is the much ballyhooed opening of the Second Avenue subway extension in 2017, a mere eighty-eight years after it was initially proposed. Even more striking than the delay were the extravagant costs, themselves a self-imposed problem of poor governance. Digging a subway in a dense urban environment necessitates disrupting delivery of gas, water, telecommunications, and so forth. Doing so efficiently in turn requires coordination so that service disruptions and alternative sources can be adjusted. The builder of the subway found coordination among the various utilities and regulatory agencies that covered each service so daunting that it decided the only solution was to dig deep into the bedrock of Manhattan so as to avoid having any contact with any other utilities or administrators.106 The result is that more than eighty years after first proposed, the Second Avenue subway finally opened in 2017, encompassing a total of four subway stops, running a grand total of about three kilometers, and pricing in at a whopping figure of almost $2 billion per kilometer.107

The capacity to cushion the dislocations of the modern global economy and the press of immigration is another measure of state competence. Germany’s capacity to integrate the former East Germany confirms the difficulty of the enterprise, even among people who already shared a language and a clear national identity. It is here that all the themes of democratic stress come together. The inability of institutional political actors to debate policy, to appeal to collective interest, and to assure through competent leadership all drain the vitality of the democratic project. Populist anger is stoked by state incompetence and increased clientelism for those with privileged access to the executive. Weakened forms of participation and deliberation, in turn, compound the sense of democratic failure.

Conclusion

The picture of democracy presented here is certainly somber, but it need not be funereal. The identified deficits in democratic governance are serious, no doubt. But the advanced industrial democracies are sophisticated societies with great internal resources. Three are worth noting here because they are significant sources of resilience. Undoubtedly there are many more, but these three flow immediately from the discussion above, and the last points back to the rule of law, a topic thus far not addressed.

First, waves of populist anger tend to be conjunctural. The immediate spark for the latest political tide appears to be the consequences of the financial crisis of 2008. Economic recovery is the likeliest source of any easing of enraged politics. But populist reaction translates poorly into governance, as the US Republican Party has shown in its hesitating transition from opposition to ruling. The current populist wave began at least a decade earlier in Latin America than in Europe or the United States, and it is now sputtering out amid corruption scandals and the inability to achieve deliverance.

Second, democratic states abound in civil-society institutions that resist the anti-liberalism of caudillo politics. One of the main failings of the Founding constitutional vision in the United States was the lack of any space for intermediating institutions that stood between the state and the citizenry. Tocqueville’s observations about the notable abundance of association in the young Republic may be generalized to all democratic countries, including the more state-oriented political orders of Europe. Even a strict Montesquieu-inspired division of government powers proved not to anticipate the manner in which democratic societies function. From the press to community associations to political parties to churches there is far more resilience than just a formal account of the separation of powers between the legislature and the executive.

Third, democratic societies develop thick legal institutions bounded by the rule of law. Moments of populist passion confront constitutional constraints and the restraining force of constitutional courts, as I addressed at length in Fragile Democracies.108 The Brexit vote provides a useful illustration. Although advocacy for popular initiatives in Britain has a long history, going back at least to Professor A.V. Dicey more than a century ago,109 the process is relatively unutilized and the relation between the subjects of referendum and ensuing governmental action remains unclear. As the House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution concluded, “[W]e regret the ad hoc manner in which referendums have been used, often as a tactical device, by the government of the day.”110

In the aftermath of Brexit, Prime Minister Cameron departed the scene and a chastened Tory government formed under Prime Minister Theresa May, itself further weakened by a disastrous gamble on rapid-fire elections. The government allowed the Brexit vote to stand as the will of the people and took the first steps toward unwinding Britain’s participation in the European Union. This provoked a legal challenge leading to a remarkable discussion in the UK Supreme Court on the nature of British democratic governance. In an approach that hearkens back to Justice Jackson’s careful dissection of the delicate balance of powers between the executive and the legislature, the Court framed the inquiry: “[The] Act envisages domestic law, and therefore rights of UK citizens, changing as EU law varies, but it does not envisage those rights changing as a result of ministers unilaterally deciding that the United Kingdom should withdraw from the EU Treaties.”111

That a weak government had appealed directly over the head of Parliament to enraged voters did not alter the institutional commitments to the democratic supremacy of Parliament. Nor could the prime minister invoke plebiscitary approval as a substitute for proper institutional process:

The question is whether that domestic starting point, introduced by Parliament, can be set aside, or could have been intended to be set aside, by a decision of the UK executive without express Parliamentary authorisation. We cannot accept that a major change to UK constitutional arrangements can be achieved by ministers alone; it must be effected in the only way that the UK constitution recognises, namely by Parliamentary legislation. This conclusion appears to us to follow from the ordinary application of basic concepts of constitutional law to the present issue.112

Rule-of-law principles may not serve to brake the more worrisome manifestations of populist anger. In some countries, as in Hungary and increasingly in Poland, the institutions may be overwhelmed by the concerted forces of politics. But they can provide a necessary challenge and an avenue of repair. In the words of the US court confronting the Trump administration’s proposed travel bans and the administration’s claims to unaccountable executive discretion:

There is no precedent to support this claimed unreviewability, which runs contrary to the fundamental structure of our constitutional democracy.

. . .

[Our cases] make clear, courts can and do review constitutional challenges to the substance and implementation of immigration policy.

. . .

[T]he Government’s “authority and expertise in [such] matters do not automatically trump the Court’s own obligation to secure the protection that the Constitution grants to individuals,” even in times of war.113

- 1Jan-Werner Müller, What Is Populism? 43 (Pennsylvania 2016).

- 2Id at 42.

- 3Id at 20.

- 4See Francis Fukuyama, The End of History?, 16 Natl Interest 3, 4 (Summer 1989) (“What we may be witnessing is not just the end of the Cold War, . . . but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”).

- 5At the peak of the democratic wave, in 2000, Freedom House listed 120 countries, 63 percent of all nations, as meeting the baseline criteria for democratic governance. Adrian Karatnycky, Freedom in the World 2000 (Freedom House, 2000), archived at http://perma.cc/7DMN-H6EX (“[E]lectoral democracies constitute 120 of the 192 internationally recognized independent polities.”).

- 6Philip Bobbitt, The Shield of Achilles: War, Peace, and the Course of History xxi–xxii (Alfred A. Knopf 2002) (“This war . . . began in 1914 and only ended in 1990. The Long War, like previous epochal wars, brought into being a new form of the State—the market-state.”).

- 7E.E. Schattschneider, Party Government 1 (Farrar & Rinehart 1942).

- 8Nancy L. Rosenblum, On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship 459 (Princeton 2008).

- 9See Ger Const Art 21.

- 10See Tom Ginsburg, Constitutions as Political Institutions, in Jennifer Gandhi and Rubén Ruiz-Rufino, eds, Routledge Handbook of Comparative Political Institutions 101, 106 (Routledge 2015) (“In our work on the Comparative Constitutions Project, [Zachary] Elkins, [James] Melton, and I identify certain core provisions to written constitutions. . . . In the nineteenth century . . . few constitutions mentioned political parties, while most written in the twentieth century do so.”).

- 11Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America 979 (Floating Press 2009) (Henry Reeve, trans) (originally published 1840).

- 12See V.O. Key Jr, Politics, Parties, and Pressure Groups 210–11, 244 (Thomas Y. Crowell 1942).

- 13See id at 243–44; Samuel Issacharoff, Outsourcing Politics: The Hostile Takeover of Our Hollowed-Out Political Parties, 54 Houston L Rev 845, 858 (2017).

- 14See Issacharoff, 54 Houston L Rev at 864–66 (cited in note 13).

- 15See id at 866–70.

- 16Richard H. Pildes, Romanticizing Democracy, Political Fragmentation, and the Decline of American Government, 124 Yale L J 804, 809 (2014).

- 17See Gerald F. Davis, Kristina A. Diekmann, and Catherine H. Tinsley, The Decline and Fall of the Conglomerate Firm in the 1980s: The Deinstitutionalization of an Organizational Form, 59 Am Sociological Rev 547, 563 (1994) (discussing the rapid shift away from the conglomerate form in the 1980s, including Gulf & Western’s reorganization as Paramount Communications); John G. Matsusaka, Corporate Diversification, Value Maximization, and Organizational Capabilities, 74 J Bus 409, 412–14 (2001) (charting acquisitions and divestments by Gulf & Western and ITT from 1958 to 1988). See also Edward B. Rock, Adapting to the New Shareholder-Centric Reality, 161 U Pa L Rev 1907, 1921–22 (2013) (describing incentives for conglomerates to spinoff “unrelated businesses” and noting such spinoffs by Sears, CBS, DuPont, and AT&T).

- 18See generally David Weil, The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It (Harvard 2014).

- 19For a more detailed discussion of how direct-democratic procedures, such as direct appeals to voters by populist candidates, weaken political parties, see Emanuel V. Towfigh, et al, Do Direct-Democratic Procedures Lead to Higher Acceptance Than Political Representation? Experimental Survey Evidence from Germany, 167 Pub Choice 47, 49 (2016).

- 20Id at 48–49.

- 21Peter Mair, Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy 43 (Verso 2013).

- 22See Harald Schoen and Robert Greszki, A Third Term for a Popular Chancellor: An Analysis of Voting Behaviour in the 2013 German Federal Election, 23 German Polit 251, 251 (2014):

In the 2013 German federal election, the trend towards increased electoral volatility and fragmentation continued. . . . [I]n the 2009 election the conservative CDU/CSU fought a personalised campaign in which it aimed successfully to capitalise on Merkel’s increased popularity. In the 2013 election, the CDU/CSU campaign was, once again, focused on Chancellor Merkel, who was now the unchallenged leader of her party.

- 23See generally Chris J. Bickerton and Carlo Invernizzi Accetti, Democracy without Parties? Italy after Berlusconi, 85 Polit Q 23 (2014) (describing fragmentation across the spectrum of Italian politics). See also Marc Bühlmann, David Zumbach, and Marlène Gerber, Campaign Strategies in the 2015 Swiss National Elections: Nationalization, Coordination, and Personalization, 22 Swiss Polit Sci Rev 15, 25 (2016) (“[T]he personalization with nationwide ‘party stars’ is a new phenomenon in Switzerland.”).

- 24See, for example, Hermann Schmitt, Sara Hobolt, and Sebastian Adrian Popa, Does Personalization Increase Turnout? Spitzenkandidaten in the 2014 European Parliament Elections, 16 EU Polit 347, 347–48 (2015):

The 2014 European Parliament elections were the first elections where the major political groups each nominated a lead candidate (Spitzenkandidat) for the Commission presidency in the hope that this would increase the visibility of the elections and mobilize more citizens to turn out.

. . .

The potential to increase political participation was . . . at the heart of the European Commission’s support for the Spitzenkandidaten innovation, as they hoped this could ‘contribute to raising the turnout for European elections.’

- 25See Pedro O.S. Vaz de Melo, How Many Political Parties Should Brazil Have? A Data-Driven Method to Assess and Reduce Fragmentation in Multi-party Political Systems, 10 PLOS One 1, 2 (Oct 14, 2015), archived at http://perma.cc/27ZA-2EY2.

- 26Mair, Ruling the Void at 16 (cited in note 21).

- 27See David Cameron Promises In/Out Referendum on EU (BBC, Jan 23, 2013), archived at http://perma.cc/DAG4-RGHX (describing pressures that Cameron faced from within his own Conservative Party and from challenger UKIP that pushed him to call for the Brexit referendum); Tom McTague, Alex Spence, and Edward-Isaac Dovere, How David Cameron Blew It (Politico, Sept 12, 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/X4AP-MGL2 (describing organizational and legislative failures by Cameron’s Conservative Party preceding the Brexit referendum).

- 28See, for example, Andres Auer, European Citizens’ Initiative: Article I-46.43 1 Eur Const L Rev 79, 79 (2005) (outlining the EU’s “new device of participatory democracy”).

- 29Jeremy Shapiro, Brexit Was a Rejection of Britain’s Governing Elite. Too Bad the Elites Were Right. (Vox, June 25, 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/9586-AQA7.

- 30See Jason Horowitz, Italy’s Premier, Matteo Renzi, Says He’ll Resign after Reform Is Rejected (NY Times, Dec 4, 2016), online at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/04/world/europe/italy-matteo-renzi-referendum.html?smid=pl-share&_r=0 (visited Oct 11, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable) (“Prime Minister Matteo Renzi said he would resign after voters decisively rejected constitutional changes.”).

- 31Russell J. Dalton, Wilhelm Bürklin, and Andrew Drummond, Public Opinion and Direct Democracy, 12 J Democracy 141, 141 (Oct 2001).

- 32What’s Gone Wrong with Democracy (The Economist, Mar 1, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/2KWC-8XCH.

- 33Trends in Party Identification, 1939–2014 (Pew Research Center, Apr 7, 2015), archived at http://perma.cc/N9C8-SZBM.

- 34See generally J. David Greenstone, Labor in American Politics (Knopf 1969) (documenting American labor’s symbiotic relationship with the Democratic Party through the first half of the twentieth century); Peter L. Francia, Assessing the Labor-Democratic Party Alliance: A One-Sided Relationship?, 42 Polity 293 (2010) (contrasting modern organized labor’s continued support for Democratic candidates with Democratic failures to deliver pro-labor policy).

- 35See generally Daniel Ziblatt, Conservative Parties and the Birth of Democracy (Cambridge 2017) (chronicling the organizational rise of the British and German conservative parties).

- 36Megan Dunn and James Walker, Union Membership in the United States *2–4 (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Sept 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/5VPC-YDKB.

- 37The concern over the legal implications of the distinct role of public-sector unionism in the United States goes back at least to Harry H. Wellington and Ralph K. Winter Jr, The Limits of Collective Bargaining in Public Employment, 78 Yale L J 1107, 1116, 1124–25 (1969).

- 38David Brodwin, The Chamber’s Secrets (US News & World Report, Oct 22, 2015), archived at http://perma.cc/8SJU-E53D. See also generally Alyssa Katz, The Influence Machine: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Corporate Capture of American Life (Spiegel & Grau 2015).

- 39Brodwin, The Chamber’s Secrets (cited in note 38):

Founded in 1912, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce has been shaped by its CEO Tom Donohue into a powerful lobbying and campaigning machine that pursues a fairly narrow special-interest agenda. It’s now the largest lobbying organization in the U.S. (ranked by budget). It mostly represents the interests of a handful of so-called “legacy industries”—industries like tobacco, banking and fossil fuels which have been around for generations and learned how to parley their earnings into political influence. The Chamber seeks favorable treatment for them, for example, through trade negotiations, tax treatment, regulations and judicial rulings.

- 40Id. See also Katz, The Influence Machine at xiii (cited in note 38) (discussing the “undisclosed financial contributions to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce” made by “industries that provide vital goods and services but at mounting costs to society”).

- 41Joshua Cohen, Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy, in Alan Hamlin and Philip Pettit, eds, The Good Polity: Normative Analysis of the State 17, 17 (Basil Blackwell 1989).

- 42Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy 250 (George Allen & Unwin 1976) (originally published 1942).

- 43Cohen, Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy at 21–26 (cited in note 41).

- 44See Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy at 247–49 (cited in note 42).

- 45See Cohen, Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy at 18–20 (cited in note 41).

- 46Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy at 248–49 (cited in note 42).

- 47See George Packer, The Empty Chamber (New Yorker, Aug 9, 2010), archived at http://perma.cc/SR7D-72JJ.

- 48Hitler’s regime consolidated power through a number of direct referenda in the 1930s, including those withdrawing Germany from the League of Nations and combining the offices of chancellor and president into that of the führer. These referenda were initiated and controlled by the German executive branch. See generally Arnold J. Zurcher, The Hitler Referenda, 29 Am Polit Sci Rev 91 (1935). In Italy, Mussolini maneuvered to give the Fascist Grand Council the power to approve election lists throughout the 1920s, shifting the Italian parliament from a deliberative (though gridlocked) electoral body to a single-party “Corporative Chamber” approved by popular plebiscite: “Our aim is to create a Corporative Chamber without an opposition. We have no desire nor need for any political opposition.” The Fascist Grand Council and the Italian Election, 5 Bull Intl News 3, 4 (1929) (quoting Mussolini).

- 49Conrado Hübner Mendes, Constitutional Courts and Deliberative Democracy 14 (Oxford 2013).

- 50Id at 15.

- 51Statistics and Historical Comparison (GovTrack), archived at http://perma.cc/3BVH-AT7D (showing that the 95th Congress passed 804 bills while the 114th Congress passed 329).

- 52See generally Samuel Issacharoff, Fragile Democracies: Contested Power in the Era of Constitutional Courts (Cambridge 2015).

- 53Julia Azari, A President’s First 100 Days Really Do Matter (FiveThirtyEight, Jan 17, 2017), archived at http://perma.cc/852T-G5DF.

- 54The major congressional actions took the form of an expedited procedure to withdraw regulatory decrees within a fast-track window. There were no new legislative initiatives of any substance. See David Leonhardt, Donald Trump’s First 100 Days: The Worst on Record (NY Times, Apr 26, 2017), online at http://nyti.ms/2pleYVE (visited Oct 11, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable).

- 55See Kenneth J. Arrow, A Difficulty in the Concept of Social Welfare, 58 J Polit Economy 328, 328–31 (1950) (discussing the confusion attendant to any attempt to amalgamate the social and voting preferences of a diverse whole).

- 56See generally id (laying out Arrow’s impossibility theorem and the inevitability of preference cycling). See also Richard H. Pildes and Elizabeth S. Anderson, Slinging Arrows at Democracy: Social Choice Theory, Value Pluralism, and Democratic Politics, 90 Colum L Rev 2121, 2183–86 (1990) (arguing that institutional arrangements may mediate Arrow’s predicted cycling).

- 57Ray v Blair, 343 US 214, 221 (1952).

- 58See generally Samuel Issacharoff and Richard H. Pildes, Between Civil Libertarianism and Executive Unilateralism: An Institutional Approach to Rights during Wartime, 5 Theoretical Inquiries L 1 (2004) (surveying the response of American courts in periods of crisis when the executive asserts a need for unilateral action).

- 59Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co v Sawyer, 343 US 579, 636–38 (1952) (Jackson concurring).

- 60Id at 637 (Jackson concurring).

- 61Id (Jackson concurring).

- 62How this conflict plays out is the subject of Rosalind Dixon and Samuel Issacharoff, Living to Fight Another Day: Judicial Deferral in Defense of Democracy, 2016 Wis L Rev 683, 706.

- 63See notes 108–12 and accompanying text.

- 64See generally House of Lords Select Committee on the Constitution, Waging War: Parliament’s Role and Responsibility (HL Paper 236-I, July 26, 2006), archived at http://perma.cc/MF99-F78K.

- 65Pub L No 93-148, 87 Stat 555 (1973), codified as amended at 50 USC § 1541 et seq.

- 66Waging War at *5 (cited in note 64) (“The purpose of our inquiry has been to consider what alternatives there are to the use of the Royal prerogative power in the deployment of armed force . . . and in particular whether Parliamentary approval should be required for any deployment of British forces outside the United Kingdom.”). In the following years, the interplay between the prime minister and Parliament developed informally, until the point in 2014 when “the prime minister acknowledged that a convention of Commons approval now existed.” Philippe Lagassé, Parliament and the War Prerogative in the United Kingdom and Canada: Explaining Variations in Institutional Change and Legislative Control, 70 Parliamentary Aff 280, 289 (2017).

- 67Brown Calls for MPs to Decide War (BBC News, Apr 30, 2005), archived at http://perma.cc/86MH-QDHX.

- 68See The Report of the Iraq Inquiry: Executive Summary, HC 264, 58, 83 (July 6, 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/H5T3-EWNR (critiquing Blair’s actions, the report noted that “there should have been a collective discussion by a Cabinet Committee or small group of Ministers on the basis of inter-departmental advice agreed at a senior level between officials at a number of decision points which had a major impact on the development of UK policy before the invasion of Iraq”).

- 69See, for example, Michael Foley, The British Presidency: Tony Blair and the Politics of Public Leadership 108 (Manchester 2000) (noting “that Blair and his followers operated on the assumption that parliament was no longer a central force of political significance”); Zachary Karabell, How the GOP Made Obama One of America’s Most Powerful Presidents (Politico, Apr 14, 2016), archived at http://perma.cc/AN8D-BBHE (positing that Republicans in Congress as “the so-called Party of No only provoked the Obama administration into finding innovative ways to exercise [greater unilateral] power . . . . Rather than containing the White House, congressional Republicans liberated it”).