Comparative Constitutional Matching: From Most Similar Cases to Synthetic Control?

Comparative constitutional law (CCL) is a diverse field employing multiple different methods.1 Increasingly, however, comparative constitutional scholars are turning their attention to the causal link between various features of constitutional systems and outcomes of interest. This is what Ran Hirschl has labeled the turn from “comparative constitutional law” (CCL) to “comparative constitutional studies” (CCS).

Causally oriented inquiry of this kind aims to understand two different aspects of constitutional practice—first, what drives the adoption of certain constitutional norms and structures; and second, what the causal impact of those norms is likely to be. It also relies on two broad methods: small-n, qualitative methods that rely on principles of case-selection developed in comparative politics; and large-n, quantitative methods that seek to draw causal inferences from the study of a large set of countries over time.

Adam Chilton and Mila Versteeg’s outstanding new book, How Constitutional Rights Matter, fits into this second tradition. They also go beyond existing empirical approaches and rely on a combination of propensity-score matching and event study–based approaches to try and identify truly causal relationships between the adoption of constitutional rights and the protection of certain interests. For instance, does enshrining a right to religious freedom mean that religious organizations are more likely to be able to build houses of worship and hold religious services, free of harassment or intimidation? Does enshrining a right to housing in a constitution increase government spending on social housing, or reduce homelessness or income inequality? Does it provide some other broader benefit? These and related questions are the sorts of questions that Chilton and Versteeg ask, and matching provides a promising tool for answering these questions.

Matching methods (such as propensity-score matching, nearest-neighbor matching, and Mahalanobis-distance matching) create counterfactual country experience and thus assess the impact of constitutional provisions such as rights guarantees. They are promising advances in the toolkit used by comparative constitutional scholars. In this short Essay, however, we suggest that matching techniques also have important limitations in a constitutional context: it is often extremely difficult to identify an appropriate country match. Similar challenges can arise when applying the “most similar” cases principle, which is the equivalent to matching in small-n research.

One response to this difficulty, we suggest, may also lie in a turn from matching to new empirical methods based on a form of “synthetic control.” Our main goal is to offer a suggestion about a productive next step in causal inference in CCS. To that end, we briefly outline the synthetic control approach, which has been influential in economics and political science in recent years, and argue that it has considerable promise for empirical work in comparative constitutional law. In particular, we suggest that synthetic control not only addresses the technical issues with matching, but also addresses an important conceptual issue with the use of empirical methods in CCL. That latter concern is the degree to which “every country is special” and “every constitutional moment is sui generis.” Unlike matching methods, which necessarily group country-year observations into two groups (treated and control), synthetic control allows research designs that either treat a single country as the treated unit or pool together countries that experienced a similar intervention. In fact, one can do both with synthetic control.

I. Matching and the Most-Similar-Cases Principle

Propensity Score Matching (PSM) is a hugely popular technique in social science. Indeed, it has been used or referenced in more 141,000 articles.2 And one of the most promising developments toward providing causal inference in comparative constitutional studies in recent years has been the use of various matching methods. As Chilton and Versteeg put it, “[t]he goal of matching is to pair observations that have been ‘treated’ with a variable of interest with observations that are similar in all theoretically relevant ways but have not received the ‘treatment.’ In our case, this means matching country-year observations from countries with a specific constitutional right to country-year observations from similar countries without the same right.”

This is exactly the right framing. One wants to think about potential outcomes: the value of a unit’s outcome variable after application of the treatment and that same value under non-application (i.e., control). Often, comparativists are claiming, either explicitly or implicitly, that something of interest happened in country a (or some set of countries) that did not happen in country b (or some set of countries) and that we can learn something useful about what would have happened to an outcome we care about by considering the following counterfactual: what would have happened if country b did the same thing that country a did? Since country b didn’t actually do that “thing,” in some sense we will never know the answer to the counterfactual question.

Yet getting around that difficulty is precisely what modern causal inference is all about. Indeed, Rubin’s “potential-outcomes framework” poses the counterfactual comparative question above in explicitly statistical terms, and this framework has guided the development of methods of causal inference ranging from randomized controlled trials, to instrumental variables, difference-in-differences, regression discontinuity, and other research designs—including matching itself.

An approach of this kind also approximates the “most similar cases” principle used by qualitative researchers in comparative constitutional studies. As Hirschl explains, the idea of the most-similar-cases principle is that researchers should select two countries for comparison that are as similar as possible on all relevant background dimensions, but different along the key variable of interest. This also attempts to approximate large-n techniques that control for relevant differences across countries, seeking to understand the causal impact of certain constitutional variables.

There are, however, some well-known and widely acknowledged technical issues with different matching estimators. One of the strongest criticisms, made by King and Nielsen, is that, far from removing bias, PSM may actually make bias worse. It is also well known that various matching estimators have questionable large-sample properties, which calls into question their use in “large-n” analysis. To be more precise, such estimators are non-smooth functionals of the underlying data and are not N1/2 consistent—a basic requirement for use in the type of applied work at issue in CCL. The conditions under which they are consistent in this fashion are quite stringent.

Beyond these technical yet pressing issues, there is also an important question of interpretation of matching estimators as applied in CCS. As Chilton and Versteeg emphasize, “[t]he key assumption of the method is that, after matching on relevant observable variables, the only difference between the observations that will affect the outcome is the treatment.” Of course, all identifying assumptions are stark when stated plainly. But matching in its traditional forms (propensity-score, nearest-neighbor, Mahalanobis-distance) has strong embedded functional-form and other assumptions.

Similar issues arise when applying the most-similar-cases principle, but the difficulties are often more transparent. This principle also means attempting to “match” countries with sufficient similarities across at least four dimensions: the relevant text or language of a particular constitutional provision; relevant constitutional structures; the general legal tradition and history of a given constitutional system; and a country’s broader sociopolitical values, both generally and as they relate to the issue or question under study. In reality, this will be a near-impossible task: at best, one can hope to identify countries with substantial similarities across many of these dimensions, even while acknowledging that they inevitably differ along others. But this will often be apparent to readers, where relevant differences are less apparent in large-n matching approaches.

In the next Part, however, we suggest that a partial solution to these difficulties is a turn toward synthetic control in large-n studies.

II. Towards Synthetic Control?

The Synthetic Control estimator (SC) was first developed by Abadie and Gardeazabal. It uses a data-driven procedure to create a comparison unit in comparative case studies. These case studies can, in principle, be any policy intervention: a longer school day for elementary-school students, the introduction of a carbon tax, or the granting of socioeconomic rights, to name a few.

The primitives of the SC estimator are samples of J + 1 units which, in the context of CCL, might best be thought of as countries. Unit j = 1 is the country of interest or the treated unit and units j = 2, … , J + 1 are the comparison units or donor pool. For each of these units there are data for T0 periods before the intervention, and T1 time periods post intervention.

Since the object of the exercise is to create a combination of units from the donor pool to mimic the treated unit—to create a synthetic control—the analyst uses data on pre-intervention characteristics of the treated unit and the donor pool. For the treated unit, these characteristics are collected in a vector X1 of values, and for the donor pool they are contained in an analogous matrix X0, consisting of the same variables.

The difference between the preintervention characteristics of the treated unit and the synthetic control comprised of a weighted combination of the donor pool is the vector X1 – X1W. One then picks the synthetic control W* that minimizes this difference. A series of papers by Abadie and coauthors detail the SC method. It is worth noting that, from a practical perspective, SC can now be easily implemented in popular and widely used statistical packages such as Stata, Matlab, or R.

A. Synthetic Control and German Unification

Adadie, Diamond, and Hainmuller provide an illustration of the SC method in a political science context. The question they study is: what was the causal effect of German reunification on the gross domestic product (GDP) of West Germany? While, of course, there were many economic and noneconomic reasons for reunification, understanding the economic consequences of political integration is an important issue. Prior to German reunification in 1990, the per-capita GDP of West Germany was approximately three times higher than that of East Germany. What would have happened to West German GDP absent reunification?

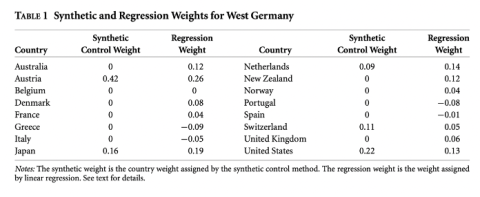

Adadie, Diamond and Hainmuller use the SC method to construct a counterfactual or “synthetic” West Germany, comprised of a weighted average of 16 OECD countries. In fact, it turns out that only five of those 16 countries get positive weights: Austria, Japan, Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United States. This is shown in the following table, which also demonstrates that the weights in the SC method in principle differ from those that would come from constructing a counterfactual using a linear regression. This points to one of the advantages of the SC method—that it does not rely on out-of-sample extrapolation in the way that some other methods do.

Source: Adadie, Diamond, and Hainmuller (2015).

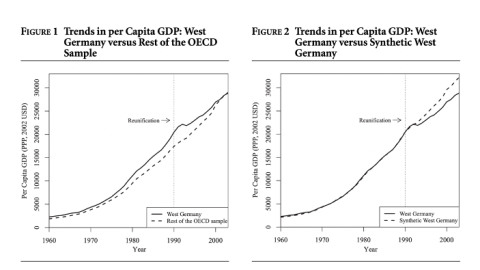

Adadie, Diamond, and Hainmuller go on to illustrate—as the chart below from their paper highlights—that the synthetic West Germany that they construct mimics actual pre-1990 West Germany very closely. The divergence between the solid and dashed lines post-reunification can then be interpreted as the causal effect of reunification on West German GDP. As the authors put it, “our results suggest a pronounced negative effect of the reunification on West German income. We find that over the entire 1990–2003 period, per capita GDP was reduced by about 1,600 USD per year on average, which amounts to approximately 8% of the 1990 baseline level. In 2003, per capita GDP in the synthetic West Germany is estimated to be about 12% higher than in the actual West Germany.”

B. Synthetic Control and Abortion

These same techniques could also readily be applied in a constitutional context. Consider an attempt to understand the effect of German unification on the German Federal Constitutional Court’s approach to abortion. In the Abortion I Case,3 the German Federal Constitutional Court held that West German law legalizing access to abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy was inconsistent with the Basic law and its guarantee of the life and dignity of the fetus.4 The Bundestag, the Court held, was obliged to adopt a regulatory scheme for the “protection of the unborn,” and while it had broad scope to determine the most effective scheme of this kind, that discretion was not unlimited. The response, from the Bundestag, was also to enact new laws prohibiting abortion but providing a range of exceptions or defenses—where pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, the fetus was severely impaired, or the pregnancy threatened a woman’s life or health. In addition, it provided that abortion would not be criminally prosecuted in other circumstances, providing a woman submitted to a form of explicitly pro-life counselling before obtaining an abortion.

Over time, however, there was mounting pressure on this compromise, and the Bundestag sought to expand access to abortion further, including by providing expanded state funding for abortion. This also led to further litigation, including the decision of the German Federal Constitutional Court in the Abortion II Case5 in 1993. The Abortion II Case upheld the capacity of the state to decriminalize abortion, provided it continued to encourage women to continue a pregnancy to term, but imposed constitutional limits on the permitting and funding of non-indicated abortions.

One question comparative scholars, especially those interested in “dialogue” or “weak” forms of judicial review, might ask is what caused this shift on the part of the German Federal Constitutional Court: was the decision a response to dialogue or pressures to revisit the Court’s earlier decision in light of democratic disagreement within both West and East Germany? Or was it a decision that effectively updated the compromise struck in the Abortion I Case in order to respond to German unification, and the larger number of pro-choice voters who entered Germany as a result of unification? Contraception and abortion were widely available in East Germany prior to unification, and many East German women demanded continued access after unification.

Synthetic control also provides a potential means of answering this question.

To answer the question, researchers would need to construct a “synthetic West Germany” based on countries with comparable economic and legal indicators, and in particular, comparable access to abortion at the time of unification. It would then compare this synthetic West Germany to the actual German experience of abortion after unification in order to understand whether a dialogical or updating account provides the best explanation for changes in the German Court’s jurisprudence.

Of course, an approach of this kind would involve complex and difficult judgments about what “comparable” access to abortion meant in this context (for example, would it simply be actual legal access, or include an affirmation of fetal rights as part of the relevant constitutional framework?) But judgments of this kind are inevitable in any form of causally oriented form of comparison. And synthetic control offers a more fine-grained approach to judgments of this kind than techniques such as matching, which make more aggregate, high-level judgments about similarities between countries.

Synthetic control techniques could likewise be used to understand the causal effects of constitutional-rights provisions and decisions on various outcome variables. There is a long list of topics where techniques of this kind could be used, including many of the topics addressed by Chilton and Versteeg in their important new book. But consider abortion as an example: one of the questions frequently posed in the abortion context is whether criminalization of abortion in fact deters access, and thereby promotes fetal life, or simply leads to more unsafe, illegal abortion. And synthetic control could again help answer this question: by constructing a synthetic comparator for a country that moves toward more restrictive abortion laws (such as, for example, in Honduras in 2009 or Poland in 2020), it would allow a more accurate understanding of the causal impact of limiting legal access to abortion.

III. Conclusion

Quantitative and qualitative approaches to comparative constitutional studies are often seen as quite different. And while some scholars, such as Chilton and Versteeg, are seeking to bring the two approaches closer together by using qualitative case studies to test the “plausibility” of quantitative findings, the divide remains real. No qualitative scholar would start with the hypothesis that Chilton and Versteeg test, and no existing large-n databases include all of the variables of interest to those who do qualitative work.

However, synthetic-control techniques offer the potential to help close this divide. One of the limitations of current small-n studies that rely on the most-similar-cases principle is that it is often difficult to identify any one country as “most similar” to another on all relevant dimensions. A turn to synthetic comparison also provides an important means of addressing this concern.

Similarly, one of the limitations of existing quantitative studies, including those that rely on matching, is that they ignore fine-grained differences in judicial practice or legal culture between countries. And again, synthetic control techniques offer a means of addressing this: they allow researchers to construct a synthetic country with the same formal constitutional attributes, and similar decision patterns, as the country under study.

In this sense, the synthetic-control method not only holds out the promise of a technical improvement upon current matching or event-study methods used in CCS, but also could create a bridge between small n and large n studies. By forcing researchers to think in a clear way about what the true counterfactual is, and hence what the true source of variation is in any CCS study, it holds out the promise of improving both qualitative and quantitative studies in the field. And as a technique that arguably falls between a quantitative and qualitative approach, it draws on the strength of both approaches, and encourages more cross-validation between qualitative and quantitative approaches. For that reason alone, it seems worthy of further investigation as a tool for comparative constitutional studies.

- 1Rosalind Dixon, Comparative Constitutional Modalities: An Essay in Honor of Mark Tushnet (Work in progress, 2020).

- 2Gary King & Richard Nielsen, Why Propensity Scores Should Not Be Used for Matching, 27 Political Analysis 435, 435 (2019). For the origins of these techniques, see Paul R. Rosenbaum & Donald B. Rubin, The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects, 70 Biometrika 41 (1983).

- 339 BVerfGE 1 (1975).

- 4For a discussion of Abortion I, see John D. Gorby, Introduction to the Translation of the Abortion Decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of the Federal Republic of Germany, 9 J. Marshall J. Prac. & Proc. 557 (1976). See also Abortion II Case, 88 BVerfGE 203 (1993); Donald P. Kommers, The Constitutional Law of Abortion in German: Should Americans Pay Attention?, 10 J. Contemp. Health L. & Pol’y 1 (1994).

- 588 BVerfGE 203 (1993).