Constitutional Comprehensibility and the Coordination of Citizens: A Test of the Weingast-Hypothesis

It has been argued that easily comprehensible constitutions can help citizens in acting collectively and opposing their government, should it transgress constitutional limits (we call this the “Weingast hypothesis”). To test this hypothesis, we generate constitutional comprehensibility indices. However, based on these indices, we find only scant support for the Weingast hypothesis. Reassuringly, we find that higher levels of constitutional compliance by the executive are associated with less politically motivated mass protest.

I. Introduction

Some constitutions promise paradise on earth. It is, therefore, not surprising that in many countries constitutional reality does not keep pace with constitutional promise. The difference between constitutional promises and constitutional reality can be described as a de jure-de facto gap. Why this gap is large in some countries, but rather small in others, might be one of the most important research questions for constitutional scholars.1

One explanation for noncompliance, offered most clearly by Professor Barry R. Weingast, revolves around the ambiguity of the constitutional document. If the meaning and implications of the text are crystal clear and government behavior can be evaluated as either violating the constitution or complying with it, then it will be easier for citizens to hold the government accountable for constitutional violations. The clarity of the constitution can, hence, be interpreted as a factor facilitating citizens’ collective action vis-à-vis their government.2

To date, Weingast’s argument has not been tested because no measure for the comprehensibility of constitutions was available. Here, we introduce indicators that measure the comprehensibility of constitutions. They are based on a measurement tool originally developed to determine the readability of texts given to students. We find that there is substantial variation in constitutional comprehensibility. Our new indicators allow us to test whether higher levels of comprehensibility are, indeed, associated with a higher likelihood of protest.

We offer two contributions to the literature. First, while there is a small literature that has used text analysis tools to understand the basic properties of constitutions, this is the first study to measure the comprehensibility of constitutional text. Second, we add to another small literature that tries to empirically test the different predictions of Weingast’s political economy model. Professors Timothy N. Cason and Vai-Lam Mui, for example, study the role of communication in coordinating citizens’ resistance in lab experiments. However, coordination via communication, as studied by Cason and Mui, is difficult when many actors are involved or when free speech is (socially or politically) suppressed. Thus, constitutions can facilitate coordination via communication or even substitute for communication in the coordination of resistance. We provide the first test for whether constitutional text can serve the citizens as a coordination device. We do not find robust evidence in favor of this hypothesis, which suggests that making constitutions more comprehensible is not a silver bullet for making politicians comply with their constitution.

The rest of this Essay is organized as follows: Part II spells out the theoretical underpinnings of the new comprehensibility indicators and Part III describes the new indicators in detail. Part IV presents our empirical analysis and discusses our findings, before Part V concludes.

II. Theory

Constitutions are the most fundamental layer of the formal institutions of the nation state. Passing and enforcing statutory legislation is legitimized by reference to the constitution. Constitutions themselves need to be self-enforcing, i.e., the various actors involved in their implementation need to be given sufficient incentives to comply with the constraints of the constitution, rather than to violate them. It has been argued that the separation of powers is one important means to increase the likelihood of constitutional compliance, because if all actors involved in the separation of powers meticulously guard their competences, they are likely to foil most attempts by others to overstep their respective competences. However, in practice many constitutions are violated by those who govern, which casts doubt on the ability of the separation of powers alone to make constitutions self-enforcing.

Citizens could play an important role in incentivizing those who govern to comply with the constitution. If attempts to breach constitutional rules are met with fervent opposition, this will make such attempts costly and, hence, less likely to occur. For opposition to emerge, citizens need to overcome the dilemma of collective action. People frequently do not manage to act collectively, even if they have virtually identical preferences, because of every individual’s temptation to free ride on the efforts of the others. This dilemma of collective action is amplified here by the fact that citizens first need to agree that the government is indeed transgressing the constitution.

To attain agreement on the illegitimacy of government actions, the content of the constitution needs to be as easily and unambiguously comprehensible as possible. Only then can the constitution serve as a focal point, allowing citizens to coordinate their behavior and to jointly oppose the government. The notion of focal points was introduced by Professor Thomas Schelling, who argued that people might be able to solve complex coordination problems by drawing on the salience of particular outcomes or actions.3

Weingast develops a very similar argument, envisioning a coordination game played by a government and two citizens. The government can transgress the citizens’ rights, i.e., the rules of the constitution. It can only be stopped and punished if both citizens simultaneously (and without communication) exert costly effort to do so. Resistance by one citizen is costly only to that citizen, but without consequence to the government. Weingast argues that the less ambiguous a constitution is, the higher the likelihood that the citizens will be able to coordinate their behavior based on that constitution. The government only has an incentive to comply with the constitution if it expects successful coordination among the citizens.4

To function as focal points, constitutions must be easily comprehensible. After reading them, most people should come to the same conclusion regarding the permissiveness of a particular government action. If most citizens agree that this action is not in line with the constitution, successful coordination of a protest, i.e., collective action, becomes more likely.

Of course, comprehensibility may be a necessary condition for collective action, but it cannot be a sufficient condition for it. Participation in the production of a public good (here “opposition”) still comes at a cost that might be substantial. Under many regimes, opponents of the government may end up in jail, or worse. Professor Gillian Hadfield and Weingast argue that the likelihood that the opposition coordinates successfully depends on its members’ beliefs about other people’s likely actions. The law is particularly important in coordination when private preferences are falsified under perceived social pressure and are hence unobservable.

In sum, the comprehensibility of a constitution appears to be a necessary condition for the ability of citizens to coordinate their behavior should their government try to violate constitutional constraints. This is because a high level of comprehensibility facilitates a shared evaluation of government actions as being either constitutional or unconstitutional. Comprehensibility is not a sufficient condition though, because even if most citizens agree that the government has breached the constitution, collective action is still not guaranteed. In the next Part, we propose indices that measure the comprehensibility of constitutions.

III. Measuring Constitutional Comprehensibility

A. Conceptualizing Indicators

Before the comprehensibility of constitutions can be measured, comprehensibility needs to be defined. Linguists explain comprehension of a text as readers understanding the ideas that the text supposedly communicates. In light of this, the comprehensibility of a text can be defined as the aggregate effect of all relevant linguistic features of that text on comprehension. For example, if a text comprises long sentences, this feature will negatively impact the process of comprehension, but if the text is composed of simpler words, a reader will understand it more easily.

Traditionally, linguists have measured the comprehensibility of a text based on the difficulty of the individual words and the length of the sentences used in the text. Following this approach, a text is marked as less comprehensible when it includes a higher share of difficult words (typically defined as those with more syllables) or longer sentences on average. “Flesch-Reading-Ease” and the “Flesch-Kincaid-Grade-Level” are well-known examples of this conception of comprehensibility. More recently, scholars have turned to approaches that analyze deeper structural elements of a text and how those elements affect the process of comprehension. In these approaches, cohesion is the decisive linguistic trait for the comprehensibility of a text, and generally refers to elements of a text that help a reader understand the interrelationships between different elements of the text. Professor Danielle McNamara et al.’s Automated Evaluation of Text and Discourse with Coh-Metrix provides an up-to-date conception of cohesion, which is also the one adopted here. Its authors define cohesion as linguistic features of a text that guide a reader in connecting ideas in a text to each other and in connecting them to a topic of text.

As constitutions are written in technical language, traditional approaches tend to indicate only low levels of comprehensibility and fail to properly measure differences between constitutional texts. Cohesion-based measures of comprehensibility are more sensitive to differences in comprehensibility across constitutional texts, which are more subtle than simply the difficulty of individual words and the length of sentences.

We use the Coh-Metrix software to measure the comprehensibility of constitutional text. This application is well-suited for our purpose, because it was developed to measure different dimensions of cohesion in a text. An advantage of this application is that it offers aggregate indices in addition to those which focus only on a single dimension of cohesion. We choose three aggregate indices that we believe are most suitable to measure cohesion in constitutions. These are: referential cohesion, deep cohesion, and a connectivity index.

Referential cohesion measures the number of word overlaps between two sentences. The overlap can be measured locally and globally. While a local overlap refers to shared words between two adjacent sentences, a global overlap refers to shared words between one sentence and all other sentences in a text. Our first indicator of interest, the referential cohesion index, counts all meaningful words, which are shared locally and globally. When a sentence repeats a meaningful word of a previous sentence and provides new information about that word, it establishes a relationship between the previous mention of the word and some new information. For instance, in “John studies hard. John is a good student.” the word “John” is repeated in the second sentence, which reveals that there is a relationship between these two sentences. The referential cohesion index is constructed based on the number of overlaps found in the text.

To measure deep cohesion, Coh-Metrix counts the number of causal and intentional connectives in a text (examples are terms such as “because” or “therefore”). Then, the count is normalized with the number of overlaps in the text because the number of causal and intentional connectives in a cohesive text should be roughly as many as overlaps in the text which indicate relationship between two sentences. Finally, connectivity measures the relationships other than causal and intentional ones (e.g., the word “than” in the sentence: “a is greater than b”).

These three indicators provide the closest match to our definition of cohesion, while capturing different aspects of it. First, a cohesive text, according to our definition, is one in which ideas are introduced in relationship to each other. Referential cohesion captures that aspect of the definition. Second, these relationships should be clarified using different connectives. The deep cohesion index and the connectivity index measure that aspect. Finally, the indices we use as independent variables are aggregated from more detailed subindicators.

B. Describing Constitutional Comprehensibility

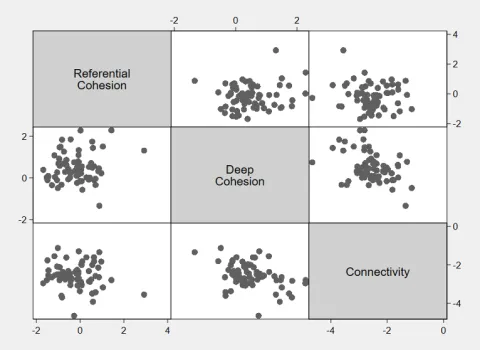

Before we move on to use our three comprehensibility indicators in evaluating the hypothesis put forward by Weingast, we outline their basic properties. Figure 1 illustrates that there are at most moderate statistical associations between the three indicators. The strongest bivariate correlation exists between our deep cohesion indicator and the indicator for connectivity (r = -0.38).

Figure 1: Constitutional comprehensibility indicators

Not only are our comprehensibility indicators not strongly correlated among each other, they also show no correlations with other important country characteristics. Democracy (as measured by the polity2-indicator), PPP-adjusted income per capita from the Penn World Table, and constitutional length (as measured by the Comparative Constitutions Project),5 are not statistically associated with any of the indicators of constitutional comprehensibility. However, countries’ legal origin is systematically associated with their constitution’s comprehensibility, with common law-countries showing significantly higher levels of referential and deep cohesion, but lower levels of connectivity than countries of other legal origins.

IV. Empirical Analysis

To estimate the ability of constitutional text to help citizens coordinate collective action against the government, we estimate the following empirical model:

$protest_{i,t} = α + β × comprehensibility_{i,t} + γ × X_{i,t} + ε_{i,t}$

Our sample covers 52 countries over the years 1990 to 2017. The models are estimated by ordinary least squares, and standard errors are clustered on the country level. The limited sample size is due to the availability of data for the different indicators used in our analysis. We chose to drop only one country, Taiwan, from the sample, as it constitutes a dramatic outlier in our indicators of constitutional comprehensibility and could therefore singlehandedly drive our empirical results. The special case of the Taiwanese constitution clearly deserves further scrutiny.

For the dependent variable, protest, we rely on two alternative indicators contained in the V-DEM 10 dataset.6 These continuous latent variables reflect the occurrence of mass mobilization (i.e., the frequency and size of mass mobilization events) to either support democracy or to support an autocratic regime. The advantage of these indicators over other indicators of protest is that they are focused on politically motivated protest and that, within this category, protest in support of democracy is distinguished from protest in support of autocracy. The Weingast hypothesis should be evaluated based on the occurrence specifically of pro-democratic protest. Our first indicator (v2cademmob) captures events that are organized to advance or protect democratic institutions, such as free and fair elections, or to support civil liberties, such as freedom of association and speech. Mass events can take different shapes, such as demonstrations, strikes, or sit-ins. Our second dependent variable (v2caautmob) captures events that are organized explicitly in support of nondemocratic political leaders and forms of government. These events are typically organized by nonstate actors, but state-orchestrated rallies are also considered.

In estimating the association between constitutional comprehensibility and protests against governments, a number of potentially important confounders, X, need to be accounted for. As we emphasized in Part II, comprehensibility alone is insufficient for opposition against government when it reneges on the constitution. To isolate the coordination-enabling effect of high levels of comprehensibility from the capacity of a society to organize for the provision of club goods and public goods, we include a variable describing the prevalence of civil society organizations, which also originates from V-Dem.

As we are particularly interested in anti-government protests that are caused by governments not complying with the constitution, a variable depicting governments’ constitutional compliance is needed. The V-Dem dataset contains a continuous latent variable “executive respect for the constitution” that ranges from “members of the executive violate the constitution whenever they want to, without legal consequences” to “members of the executive never violate the constitution.” We expect higher executive respect of the constitution to be associated with fewer protests against government. Moreover, we expect that governments’ respect for the constitution plays a bigger role in places where the constitution is more easily comprehensible (and, vice versa, constitutional comprehensibility should translate into protest only if the government indeed tries to renege on the constitution). The direct effect of constitutional compliance on the occurrence of anti-government protest can be interpreted as an alternative, weaker test of Weingast’s hypothesis.7

The propensity to protest against government is potentially also influenced by slow-moving cultural variables. In 1991 Professor Geert Hofstede et al. proposed to distinguish five cultural dimensions. Regarding one of them, which he calls “uncertainty avoidance,” he observed that citizens in countries scoring high on this cultural trait were

“pessimistic about their possibilities of influencing decisions made by authorities. Few citizens are prepared to protest against decisions made by the authorities, and their means of protest will be relatively conventional, like petitions and demonstrations. In the case of more extreme protest actions, like boycotts and sit-ins, most citizens in strong uncertainty avoidance countries favor that these should be firmly repressed by the government.”8

If people do not believe they can influence government behavior, they are unlikely to protest. This is why we control for Hofstede’s uncertainty avoidance score.

Table 1 presents our results for our first indicator of constitutional comprehensibility, referential cohesion. The first two columns in each regression table are based on the intensity of pro-democratic protest as the dependent variable, followed by two columns explaining the intensity of pro-autocratic protest. We estimate one model respectively with and without an interaction between constitutional comprehensibility and constitutional compliance. The latter model specification serves to determine if the effect of constitutional comprehensibility depends on the level of constitutional compliance, and vice versa. Regarding our control variables, we observe that uncertainty avoidance is associated with increased pro-democratic protest, which contradicts the expectation formulated by Hofstede that it should have a negative effect. However, this result only holds for two of our three dependent variables and is thus not very robust. Interestingly, we find that the existence of a strong and organized civil society is not related to more pro-democratic protest, but to significantly less pro-autocratic protest. This exact pattern holds irrespective of how constitutional comprehensibility is operationalized.

Regarding referential cohesion, we find that, consistent with our expectation and the argument formulated by Weingast, more easily comprehensible constitutions are associated with a higher likelihood of pro-democratic protest. The effect on pro-autocratic protest is not statistically significant. It does not come as a surprise that higher levels of constitutional compliance are associated with lower levels of both pro-democratic and pro-autocratic protest. However, we do not find a significant interaction between constitutional comprehensibility and constitutional compliance, i.e., their respective effects on protest are independent of each other. The unconditional effect of constitutional compliance on protest is not only highly statistically significant, but also robust to our different model specifications.9

| Variable | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-democratic protest | -0.54 | 1.10 | -2.36 | 3.69 |

| Pro-autocratic protest | -1.08 | 1.09 | -2.17 | 3.30 |

| Referential Cohesion | -0.19 | 0.73 | -1.69 | 1.43 |

| Deep Cohesion | 0.47 | 0.69 | -1.34 | 2.28 |

| Connectivity | -2.56 | 0.61 | -4.66 | -1.35 |

| Uncertainty Avoidance | 69.21 | 23.19 | 13.00 | 104.00 |

| Civil Society | 1.22 | 0.89 | -1.52 | 2.92 |

| Const. Compliance | 1.37 | 0.97 | -2.43 | 3.21 |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Avoidance | 0.015** (0.005) |

0.015** (0.005) |

-0.005 (0.005) |

-0.005 (0.005) |

| Civil Society | 0.168 (0.141) |

0.165 (0.138) |

-0.392** (0.117) |

-0.387** (0.116) |

| Referential Cohesion | 0.320* (0.144) |

0.204 (0.218) |

0.127 (0.176) |

0.323 (0.331) |

| Const. Compliance | -0.530*** (0.116) |

-0.504*** (0.109) |

-0.411*** (0.115) |

-0.455*** (0.130) |

| Ref. Cohesion*CC | 0.095 (0.132) |

-0.159 (0.179) |

||

| Constant | -0.989* (0.443) |

-1.031* (0.440) |

0.336 (0.446) |

0.407 (0.444) |

| Observations | 1,266 | 1,266 | 1,266 | 1,266 |

| Countries | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 |

Note: OLS coefficient estimates with country-clustered standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable in models (1)–(2) [/(3)–(4)] is mass mobilization for pro-democratic [/pro-autocratic] aims. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Avoidance | 0.010 (0.006) |

0.008 (0.006) |

-0.011* (0.004) |

-0.012** (0.004) |

| Civil Society | 0.106 (0.152) |

0.093 (0.147) |

-0.325** (0.117) |

-0.333** (0.117) |

| Deep Cohesion | -0.147 (0.194) |

0.264 (0.231) |

-0.373* (0.155) |

-0.105 (0.158) |

| Const. Compliance | -0.478*** (0.122) |

-0.290* (0.139) |

-0.389** (0.126) |

-0.266 (0.148) |

| Deep Cohesion*CC | -0.438* (0.164) |

-0.286* (0.129) |

||

| Constant | -0.618 (0.529) |

-0.612 (0.544) |

0.748* (0.367) |

0.752* (0.360) |

| Observations | 1,266 | 1,266 | 1,266 | 1,266 |

| Countries | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 |

Note: OLS coefficient estimates with country-clustered standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable in models (1)–(2) [/(3)–(4)] is mass mobilization for pro-democratic [/pro-autocratic] aims. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty Avoidance | 0.012* (0.005) |

0.012* (0.005) |

-0.007 (0.005) |

-0.007 (0.005) |

| Civil Society | 0.070 (0.144) |

0.072 (0.145) |

-0.437*** (0.116) |

-0.462*** (0.115) |

| Connectivity | -0.178 (0.258) |

-0.151 (0.377) |

0.118 (0.138) |

-0.163 (0.246) |

| Const. Compliance | -0.464*** (0.114) |

-0.519 (0.454) |

-0.400** (0.117) |

0.176 (0.398) |

| Connectivity*CC | -0.022 (0.182) |

0.225 (0.153) |

||

| Constant | -1.313 (0.878) |

-1.243 (1.113) |

0.812 (0.646) |

0.086 (0.826) |

| Observations | 1,266 | 1,266 | 1,266 | 1,266 |

| Countries | 52 | 52 | 52 | 52 |

Note: OLS coefficient estimates with country-clustered standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable in models (1)–(2) [/(3)–(4)] is mass mobilization for pro-democratic [/pro-autocratic] aims. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Tables 2 and 3 show results analogous to Table 1, but for them we replaced our indicator for constitutional comprehensibility with deep cohesion and connectivity, respectively. Although Table 2 does not show a significant association between deep cohesion and pro-democratic protest, the interaction term brings to light a more complex relationship. Although constitutional compliance is directly related to a reduced level of (pro-democratic and pro-autocratic) protest, a sizable share of the effect of constitutional compliance on protest depends on the comprehensibility of the constitution. Where constitutions are less comprehensible, compliance matters less to the occurrence of politically motivated protest. Just like the results in Table 1, the regression results in Table 2 appear to support Weingast’s hypothesis, although in a somewhat different fashion. However, once we move to Table 3 where an index of connectivity serves as our indicator of constitutional comprehensibility, we do not find any evidence that the comprehensibility of the constitution matters for political protest. Yet, constitutional compliance does.

To sum up our empirical results: Even with a conservative interpretation of the evidence produced by our regression analysis, we seem to have generated two important insights for constitutional scholars. The first finding is that constitutional compliance is a powerful predictor of political protest. Where the executive does not comply with the constitution, both pro-democratic and pro-autocratic protest can be expected. Our second finding is that whether and in what way the comprehensibility of the constitution matters to political protest appears to depend largely on how constitutional comprehensibility is operationalized. Based on referential cohesion, we find a direct and positive effect of constitutional comprehensibility on pro-democratic protest. Using an indicator of deep cohesion, we find that constitutional comprehensibility moderates the relationship between constitutional compliance and protest. Constitutional compliance is more effective in preventing protest where the constitution scores high on deep cohesion. Finally, if constitutional comprehensibility is operationalized as our indicator of connectivity, it does not seem to matter at all to political protest. The fact that empirical results depend dramatically on how constitutional comprehensibility is measured indicates an urgent need for further research on how it should be measured and what robustness tests should generally be performed.

V. Conclusions and Outlook

In this Essay, we have asked whether the comprehensibility of constitutions is a significant factor in determining whether a government will remain within its constitutional competences or breach the constitution. In a much cited paper, Weingast argued that more comprehensible constitutions would make it easier for citizens to coordinate and act jointly against a government that oversteps its competences. In this paper, we have tested that assertion by first creating indicators of constitutional comprehensibility and then applying them to test whether anti-government protest is indeed more likely at higher levels. The result is rather disappointing, in that it depends heavily on how constitutional comprehensibility is operationalized. However, we do find strong evidence that noncompliance with the constitution is a powerful predictor of mass protest. Further research on how constitutional comprehensibility should be measured is thus urgently needed. At this point, it is not clear whether writing easily comprehensible constitutions could help to prevent autocratic backsliding. This is consistent with previous literature, for example on the constitutional right to resist, which also suggests that a constitutional panacea cannot be expected.

- 1Stefan Voigt, Constitutional Economics: A Primer 89 (Cambridge 2020).

- 2L. L. Fuller famously names clarity as one of eight aspirational principles of legality. L. L. Fuller, The morality of the law (Yale 1969).

- 3Schelling used the example of two individuals trying to meet each other in a city without the ability to communicate. Focal meeting points could be a train station, a marketplace, city hall, or similar places. Later, Mehta et al. and Sugden and Zamarrón confronted experimental subjects with similar coordination problems and found that focal points differ substantially across cultures.

- 4This view is compatible with interpreting constitutions as sets of conventions. This interpretation is developed in more detail in Stefan Voigt’s article, Implicit Constitutional Change-Changing the Meaning of the Constitution Without Changing the Text of the Document.

- 5See also Christian Bjørnskov and Stefan Voigt’s Constitutional Verbosity and Social Trust.

- 6Pemstein et al. describe the measurement model underlying the V-DEM indicators.

- 7We consider it a weaker test because it only links rights violations to protest, but it is not clear if this protest wouldn’t also occur as a reaction to government repression in the absence of a written constitution. If, however, the comprehensibility of the written constitution can be linked to the occurrence of protest, this strongly suggests that it is the written constitution itself, and not social norms in general, that helps coordinate citizens’ collective action vis-à-vis the government.

- 8Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede & Micheal Minkov, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind 127 (1991).

- 9Note that the coefficient estimate is to be interpreted differently in models including an interaction between constitutional compliance and constitutional comprehensibility.