Knowing the Law

One important prerequisite to state compliance with higher-order legal rules is a convergence of public opinion on the existence and nature of those rules. We present original data from a nationally representative sample of U.S. residents that captures knowledge of higher-order legal norms, allowing us to explore the plausibility of the hypothesis that people have sufficient knowledge of higher-order law to enforce it. To do so, we polled U.S. residents about their positive and normative views on the existence of sixteen rights and government powers, experimentally manipulating whether the right or power flowed from constitutional or international law. We also asked respondents to state how certain they were about their positive knowledge. Our key findings are that knowledge of both constitutional and international law is limited and, relatedly, that there is not much agreement among respondents on what either requires. Yet constitutional knowledge is higher than international legal knowledge, especially for some provisions like the right to bear arms and the right to a jury trial. These findings underscore and provide an explanation for why coordinating to deter and punish constitutional violations is difficult.

I. Knowledge and the Enforcement of Higher-Order Legal Norms

Ensuring compliance with laws that constrain the state is one of public law’s central challenges. The major challenge to enforcing these laws—constitutional rules and many international treaties—is that no external enforcer is authorized to coerce the state into compliance. Unlike disputes over private contracts, property, and torts, for which a state apparatus can resolve disagreements between private citizens and coerce compliance, the social contract has no comparable external enforcement mechanism.1 For these rules—what have been called “higher-order law”2 and “[l]aw for [s]tates”—to be upheld, then, the state must be incentivized to uphold it in other ways.

In a democracy, a primary method for enforcing higher-order legal norms is the electorate’s punishment of elected officials who violate or threaten to violate them by ensuring that they are not (re-)elected. When removal from office is not immediately available, citizens can also impose costs on government officials through protest or by engaging in civil disobedience. In some systems, courts are also available to enforce constitutional rules—though, in most systems, not reliably. Both theory and a wealth of empirical evidence show that credible threats to impose these costs can deter violations at the margins.3

This mechanism, however, must necessarily overcome at least three hurdles to succeed.4 These difficulties have been analyzed extensively in legal and political science research, but they have only recently become the subject of empirical inquiry. First, citizens must value the higher-order law as law and oppose its transgression per se. Otherwise, where a majority of the electorate is indifferent to (or supportive of) violating the constitution or an international obligation, transgressing it will usually carry few consequences.5 One emerging body of literature has explored to what extent people actually oppose constitutional and international law violations per se. These studies use an experimental research design to explore whether respondents who hear that certain policies violate higher-order law are less willing to support those policies.6 The insights from this literature are mixed: citizens are sometimes positively swayed by higher-order legal norms; but, in other contexts, these norms have no effect or even backfire.7

A second obstacle to ensuring higher-order legal compliance is that the electorate must value the underlying norms enough that they are willing to take actions that impose political costs on violating governments. This challenge poses a “collective action problem.”8 Some research has explored the mechanisms by which people use higher-order legal institutions to overcome these collective action problems and promote government compliance. For instance, Beth Simmons argues that civil-society mobilization is one key to enforcing human rights treaties.9 In the book that animates this special issue, Adam Chilton and Mila Versteeg find that formal organizations—such as religious groups, trade unions, and political parties—are useful in overcoming collective action problems in constitutional enforcement. Namely, armed with the rhetorical tool of illegality, these organizations can be instrumental in coordinating the kind of collective action that makes violations costly.

The third obstacle to ensuring higher-order legal compliance is logically prior to those above: members of the electorate must have some degree of consensus about what these rules are and what constitutes breaking them. Reaching this consensus requires solving a form of coordination problem.10 Chilton and Versteeg find that formal organizations can do so by persuading the public that certain dubious government actions rise to legal violations. To illustrate, religious organizations are often critical in arguing that certain government actions—like requiring employers to provide contraceptives to their employees (in the United States) or limiting the preaching of a religion to a religious site (in Russia)—amount to constitutional violations.

Many questions remain about how to solve the fundamental coordination problem that can frustrate higher-order legal enforcement. One critical, unanswered empirical question is how much members of the electorate agree on what the higher-order legal norms are and what constitutes violating them. Such a shared understanding is at the heart of coordination problems: people must agree that certain actions violate higher-order rules before they even consider mobilizing to challenge them as illegal. Indeed, those who have conceptualized constitutional and international enforcement as coordination problems have emphasized the importance of “common knowledge”11 or shared understandings.12 They see higher-order legal norms as focal points, which allow a group of actors to agree on when to punish a government for violations.13 When legal provisions have focal power, they provide clarity on when government actions amount to violations and, as a result, give citizens something to rally around in the face of government repression.

Consider a game of tug-of-war. A team’s success depends on all the team members pulling in unison in the same direction. But pulling hard is exhausting, and people can only do it for so long (assuming they agree to pull at all).14 If members pull whenever they want and at different times, with some pulling while others rest, the team can never put much force on the rope and will certainly lose. To have any hope of winning, there needs to be a clear signal that everyone receives about when to pull and in which direction—a designated referee or captain to say: “pull now, this way!” Likewise, political mobilization that occurs haphazardly or disjointedly because not everyone agrees on when or how to move will be less successful than mobilization that is simultaneous and coordinated. A legal rule can provide that clear signal.

To what extent do constitutional and international rules actually serve as successful focal points, though? Human rights provisions are often notoriously vague: legal experts are often divided on what they require in specific situations. The lack of determinacy complicates the kind of decentralized enforcement actions that many theorists believe to be key to enforcing the rules. Vagueness is not necessarily fatal so long as there exists a consensus, that is, a shared understanding of what the higher-order rule requires. To what extent these shared understandings exist in particular contexts is an empirical question that, to our knowledge, has not yet been probed. In the next Part, we examine this question using original data from a survey conducted on a representative sample of some 3,400 U.S. residents.

II. Knowledge of Higher-Order Law: An Empirical Exploration

A. Unpacking Legal Knowledge

In conceptualizing knowledge of higher-order law, it is useful to distinguish four different concepts. First, there is positive-authority recognition. Recognition of positive authority is a positivist concept that makes the judgments of established legal authorities the arbiter of what the law is, where such a consensus exists. We believe that people are often capable of recognizing what controlling institutions and authorities say the law is, even if they disagree as to what the law should be. For instance, most people who passionately wish to outlaw abortion in the United States nonetheless appear to acknowledge that, per Roe v. Wade (1973), Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), and their progeny, courts currently recognize the constitutional right to an abortion in many circumstances. One challenge to this concept of recognition of positive authority is that the contours of many constitutional and international legal rules are not well settled. Courts, enforcement bodies, and other experts often do not know or disagree among themselves.

The second concept is shared understanding. Shared understandings of higher-order law capture the extent to which members of the electorate hold a consensus on what that law is—what it requires and forbids—regardless of whether that understanding is embraced by the designated legal authorities. For instance, there is a widespread belief among Americans that so-called “hate speech”—e.g., racist or religion-based denigration—not only should not be protected under the First Amendment’s free speech provision, but in fact is not constitutionally protected in practice. Thus, the degree of shared understanding of the constitutional law on hate speech is reasonably high. (As it happens, that shared understanding is wrong: federal courts have long recognized that such speech is, in most circumstances, protected.15 ) While there is no single threshold over which a legal norm has sufficient consensus for it to be “shared,” suffice it say that—all other things being equal—the greater the consensus, the higher the likelihood of coordinated mobilization.

Third, there is the concept of knowledge certainty, or people’s confidence in their degree of legal knowledge. A person who is very certain about her understanding of what the law says, even incorrectly, will be less susceptible to being persuaded of an alternative view. Conversely, a person who acknowledges having only a weak sense of what the law says will likely be amenable to varying arguments about what it is. An advocacy campaign to convince the public of the government’s transgressions will likely find more traction with her.

Fourth and finally, there is the concept of normative view. A normative view is a belief about what the law should be. A normative view is conceptually distinct from both what legal authorities say the law is and what lay people say the law is. Of course, understandings about what others—including legal authorities—believe the law says may influence a person’s view of what the law should be. But, as with the anti-abortion activist above, a person may recognize how the controlling law is currently understood but believe that the current interpretation is immoral or otherwise undesirable.16

For decentralized constitutional enforcement to occur, shared understandings are arguably most important of the four—almost certainly more important than actual knowledge. When many citizens agree that certain government action constitutes a transgression of some higher-order law, it is not always essential that a judge will agree; citizens can often make those actions costly regardless. Knowledge certainty, that is, how much people think they know, is also important: people need to be somewhat confident that they know the law for them to initiate enforcement action. People’s normative views are also less relevant, unless the divergence between people’s normative views and the actual constitution becomes so large that people move to change the constitutional order.17 In our experimental survey described below, we capture all four concepts.

B. Methods

We fielded a survey intended to capture each of these four concepts for both constitutional law and international law. We asked a representative sample of approximately 3,400 U.S. residents sixteen questions about rights for citizens and noncitizens, government power limitations, and the structure of government. We randomly varied (at the respondent level) whether the questions referred to constitutional law or international law. Thirteen questions referred to citizen rights and government power. For these questions, we asked the same questions for both constitutional law and international law, and respondents were asked to choose from two possible answers: “yes” and “no” (or “true” and “false”).

The three other questions were related to government structure or separation of powers. The constitutional law version of these questions varied substantively from the international law version, though they considered similar subjects, namely, representative government, high-court business, and the relationship between higher- and lower-order law. Because the thirteen questions on rights and government power were identical for constitutional law and international law, we compare knowledge across these two areas. Table 1 lists our sixteen questions, with our understanding of the agreed-on—i.e., “correct”—answer for each in brackets.

To capture knowledge certainty, we also asked respondents how confident they were about their answer to each question. For each of the questions, we asked the following: “How confident are you that your response is correct?” Respondents selected from a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (“Not At All Confident (I have no idea)”) to 5 (“Extremely Confident (I am quite certain)”). Using these answers, we calculated respondents’ perceived knowledge. Finally, to measure normative views, we asked respondents what they thought the law should be regarding that right, power, or structure, asking respondents to rate their preferences on a four-point scale.

Table 1: Sixteen Constitutional Law and International Law Knowledge Questions.

| According to prevailing interpretations of U.S. [constitutional/international] law today: |

|---|

|

Rights Questions |

| Structural Questions (correct answer in brackets) | Structural Questions (correct answer in brackets) |

|---|---|

| 14. According to the Constitution, how many senators represent each state in Congress? [answer: 2] 15. The majority of cases before the U.S. Supreme Court involve which of the following: [answer: disputes between private parties involving issues of federal law] 16. True or False: according to U.S. constitutional law, laws made by state and local governments are required to conform to the Constitution. [answer: true] |

14. According to the United Nations (UN) Charter, how many permanent members sit on the UN Security Council? [answer: 5] 15. The majority of cases before the International Court of Justice (sometimes called the World Court) involve which of the following: [answer: disputes between countries involving treaty issues] 16. True or False: according to international law, laws made by U.S. state governments are required to conform to international law. [answer: true] |

C. Results

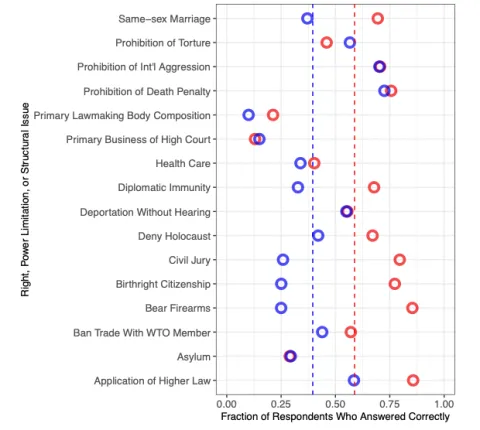

Analysis of the respondents’ answers reveals both constitutional knowledge and international legal knowledge are fairly low, although knowledge of constitutional law is higher than knowledge of international law. We should note that, for the international legal questions, we asked respondents what international law requires as it applies to the United States and used that standard in determining the correct answer.18 Figure 1 depicts the percentage of respondents who answered each question correctly. The red circles mark percentages for constitutional law; the blue circles denote the same for international law. The red dashed line marks the mean percentage across all sixteen constitutional law questions; the blue dashed line marks the same for all international law questions. Because fourteen of the sixteen questions had binary-choice answers, we are interested in the extent to which answers deviate from 50%.19 Figure 1 reveals that constitutional law knowledge is higher than 50%, which means that respondents do better than random guesses. Specifically, across the sixteen questions, the average respondent answers 58.8% of the constitutional questions correct. And if we remove the two structure questions that have multiple answers, the mean percent correct rises to 64.7%. While this is not particularly high (because someone with no knowledge at all would be expected to answer 50% of questions correctly), it is statistically significantly higher than random guessing. It is also substantially higher than international law knowledge: across the sixteen questions, the average respondent gets 39.6% of the international law questions correct (and excluding the two structure questions, 43.4%). This means that, for international law, respondents actually do worse than random guesses.

Figure 1: Percentage of Respondents Who Answered Question Correctly

Note: Plot depicts percentage of respondents who correctly identified the existence or nonexistence of higher-order provisions. Red depicts constitutional law; blue depicts international law. The vertical dashed lines represent the mean value for each type of law.

Several further observations are worth noting. First, people have substantially more knowledge in some areas of constitutional law than others. As Figure 1 shows, the right to bear arms, the right to a jury trial, and birthright citizenship are best understood, which is unsurprising considering that these rights are an important part of American popular culture. The right to asylum for noncitizens, for example, is much less well understood.

Second, it is worth noting that people give similar answers for the constitutional and international law version of a given right or limitation (even though each respondent received questions about either constitutional law or international law, not both). This finding suggests that respondents might have some latent concept of what the higher-order “law” requires, without distinguishing between the particular bodies of law. (This observation is bolstered by the fact that respondents gave similar normative responses to constitutional and international law questions, as presented in Figure 4 below.) To illustrate, approximately 75% of respondents believe that there is a right to a jury trial in both constitutional law and international law, even though this right is protected only by constitutional law.

Third, in assessing the existence of these rights and power limitations, people tend to err on the side of the right or limitation’s existence, meaning they overestimate the extent of higher-order legal protections. For example, about 60% of respondents believe the U.S. Constitution (and international law) protects the right to healthcare, even though neither does. Likewise, over 70% of respondents believe that both constitutional and international law provide a right to asylum for noncitizens, even though neither protect this right. Similarly, over 75% of respondents believe that both constitutional and international law provide a right to birthright citizenship, even though this right is protected by the Constitution only. This finding reflects that people have an overly optimistic picture of what rights are legally protected.

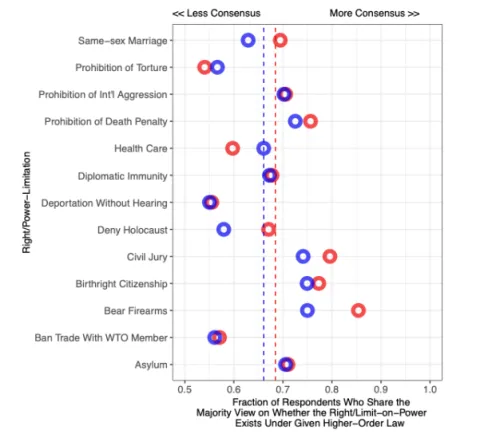

Shared understandings of both constitutional law and international law are likewise limited. Figure 2 depicts the percentage of respondents who selected the most common answer for each of the fourteen questions on rights and limitations of government for which respondents were presented with two answer choices. Here, 50% means that there are no shared understandings (because if no one had any knowledge at all and chose randomly, we would expect 50% to choose the right answer and 50% to choose the wrong answer). Across all fourteen questions, the average level of agreement for constitutional law is 68%, while for international law it is 66%. These percentages are closer together than for actual knowledge, reflecting the fact that people often assume that rights are protected both under constitutional law and international law but that the international legal rights are not in fact in effect in the United States. Figure 2 again reveals that shared understandings are highest for some rights: the right to bear arms, the right to a civil jury, and birthright citizenship. It also reveals again that levels of shared understandings are quite similar for constitutional law and international law.

Figure 2: Objective Consensus Among Respondents by Issue

Note: Plot depicts the percentage of respondents who gave the most popular response about the existence or nonexistence of the higher-order provisions. Red depicts constitutional law; blue depicts international law. The vertical dashed lines represent the mean value for each type of law.

But while knowledge and shared understandings are limited, people are nonetheless fairly confident about their legal knowledge. Figure 3 shows respondents’ self-reported confidence in each of their responses. For each right, limitation, or structural issue, it depicts a probability density function showing the distribution of responses for constitutional law (red) and international law (blue) on a five-point scale. It reveals that respondents are rather confident about their legal knowledge. The average stated level of confidence is 3.9 for constitutional law and 3.7 for international law. Thus, respondents are somewhat more confident about their constitutional law knowledge than their international law knowledge, but not by much. Perhaps more interestingly, Figure 3 reveals that people are more confident about some questions than others. The figure plots the provisions from the highest to the lowest level of constitutional law confidence, declining down each column from left to right. It reveals that respondents are most confident about the right to bear arms—not surprising, considering the many public debates surrounding this right. The right about which respondents are second-most certain—same-sex marriage—is also a widely debated topic, especially since the Supreme Court decided the issue in 2015 in Obergefell v. Hodges.

Figure 3: Confidence About Constitutional Law and International Law Knowledge

Note: Plots depict the density of respondents’ confidence about their knowledge of the existence of higher-order provisions on a-five-point scale from “Not At All Confident” (1; left) to “Extremely Confident” (5; right). Red depicts constitutional law; blue depicts international law. The vertical dashed lines represent the mean value for each type of law.

Finally, the degree of normative support varied significantly among the different provisions. Figure 4 shows the distribution of respondents’ preferences for whether each provision should exist on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (“definitely should not exist”) to 4 (“definitely should exist”). As Figure 4 shows, some rights like health care (3.26/4, constitutional; 3.25/4, international) and the right to a civil jury (3.21/4, constitutional; 3.10/4, international) are quite popular, while others like prohibiting the death penalty (2.16/4, constitutional; 2.19/4, international) and diplomatic immunity (1.86/4, constitutional; 1.87/4, international) are rather unpopular. Yet as the considerable overlap between red and yellow in each plot illustrates, whether the provision was presented as constitutional or international had little effect on respondents’ support. The mean level of support was 3.02 for constitutional law and virtually the same, 3.00, for international law. Thus, it appears that peoples’ views about the normative desirability of rights and limits is considerably stronger than their preferences for which of the two higher-order sources of law provides them.

Figure 4: Preferences for Constitutional and International Law Rights and Limits

Note: Plots depict the density of respondents’ preferences for the existence of higher-order provisions on a four-point scale from “definitely should not exist” (1; left) to “definitely should exist” (4; right). Yellow depicts constitutional law; red depicts international law. The vertical dashed lines represent the mean value for each type of law.

III. Conclusion

We make four key findings. First, people have more knowledge, as well as more shared understandings, of constitutional law than international law. Second, for both positive and normative questions, people give similar answers for the constitutional questions and the international law questions, suggesting that they have some latent concept of what higher-order “law” requires without distinguishing between the particular bodies of law. Third, in assessing the existence of these rights and power limitations, people tend to err on the side of the right or limitation’s existence, meaning they overestimate the extent of higher-order legal protections. Fourth, even though actual levels of knowledge are fairly low, people are fairly confident that they know the law, meaning that there is a discrepancy between how people rate their knowledge and their actual knowledge.

Our study was conducted in the United States, so we cannot state to what extent our findings are generalizable. It has been widely observed that the United States is unique in its attitudes towards international law and, especially, constitutional law. For international law, the United States is a global leader in the development of international law, though in some areas including human rights, the United States supports creating international norms but commits to them less dependably.20 For constitutional law, it has widely been observed that the U.S. Constitution is unusually old, short, and particularly ambiguous,21 yet nonetheless widely venerated and an important part of public discourse.22 The fact that the Constitution is part of public discourse, even a civil religion, means that knowledge and shared understandings might be higher in the United States than in other parts of the world.

Nonetheless, our core finding is that knowledge about the Constitution and international law is relatively low and, relatedly, that there exists little shared understanding of what constitutional law and international law require. While further empirical analysis is necessary, these findings showcase the challenges inherent in decentralized legal and political enforcement of higher-order law.

- 1See Adam Chilton & Mila Versteeg, How Constitutional Rights Matter 27 (2020); see also Jack Goldsmith & Daryl Levinson, Law for States: International Law, Constitutional Law, Public Law, 122 Harv. L. Rev. 1791, 1795 (2009); Daryl J. Levinson, Parchment and Politics: The Positive Puzzle of Constitutional Commitment, 124 Harv. L. Rev. 657, 662 (2011); Russell Hardin, Why a Constitution?, in The Social and Political Foundations of Constitutions 51, 53 (Mila Versteeg & Denis J. Galligan eds., 2013); Gillian K. Hadfield & Barry R. Weingast, Constitutions as Coordinating Devices, in Institutions, Property Rights, and Economic Growth: The Legacy of Douglass North 121, 122–23 (Sebastian Galiani & Itai Sened eds., 2014).

- 2By “higher-order law” we mean law that is not unambiguously inferior to federal statutes. This is true for both international law and constitutional law. See Kevin L. Cope, Congress’s International Legal Discourse,113 Mich. L. Rev. 1115, 1123 (2015).

- 3See Chilton & Versteeg, supra note 1, at 25–58.

- 4See Hadfield & Weingast, supra note 1, at 123.

- 5See generally, e.g., Kevin L. Cope & Charles Crabtree, Migrant-Family Separation and the Diverging Normative Force of International Law and Constitutional Law (2021) (unpublished manuscript) [hereinafter “Cope & Crabtree, Migrant-Family Separation”].

- 6Notable studies include: Geoffrey P.R. Wallace, International Law and Public Attitudes Toward Torture: An Experimental Study, 67 Int’l Org. 105 (2013); Adam S. Chilton, The Influence of International Human Rights Agreements on Public Opinion: An Experimental Study, 15 Chi. J. Int’l L. 110 (2014); Geoffrey P.R. Wallace, Martial Law? Military Experience, International Law, and Support for Torture, 58 Int’l Stud. Q. 501 (2014); Yonatan Lupu & Geoffrey P.R. Wallace, Violence, Nonviolence, and the Effects of International Human Rights Law, 63 Am. J. Pol. Sci. 411 (2019); and Adam S. Chilton & Mila Versteeg, International Law, Constitutional Law, and Public Support for Torture, Res. & Pol., Jan.–Mar. 2016, at 1.

- 7The following studies document backfire effects: Kevin L. Cope & Charles Crabtree, A Nationalist Backlash to International Refugee Law: Evidence from a Survey Experiment in Turkey, 17J. Empirical Legal Stud. 752 (2020); and Cope & Crabtree, Migrant-Family Separation, supra note 5.

- 8Chilton & Versteeg, supra note 1, at 32; see also id. at 32–33; William H. Riker & Peter C. Ordeshook, A Theory of the Calculus of Voting, 62 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 25 (1968); Thomas R. Palfrey & Howard Rosenthal, A Strategic Calculus of Voting, 41 Pub. Choice 7 (1983); Jon Elster, Rationality, Morality, and Collective Action, 96 Ethics 136 (1985).

- 9Beth A. Simmons, Mobilizing for Human Rights: International Law in Domestic Politics (2009).

- 10See Chilton & Versteeg, supra note 1, at 30–31.

- 11Hadfield & Weingast, supra note 1, at 123 (arguing that “to coordinate the enforcement actions of willing participants, individuals must all share similar beliefs about what the law requires[—]what is right and what is wrong” and that “all these beliefs must be common knowledge”).

- 12See generally James D. Morrow, Order Within Anarchy: The Laws of War as an International Institution (2014).

- 13See Barry R. Weingast, Political Foundations of Democracy and the Rule of Law, 91 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 245, 246 (1997) (describing these points as stable “focal solution[s]”). For a critique, see Chilton & Versteeg, supra note 1, at 31.

- 14Separately, a tug-of-war also involves a potential collective action problem, in that members of the team may be incentivized to free ride on others’ efforts if, for any given team member, the marginal cost of his pulling exceeds the value derived from the marginal increase in chance of victory that his pulling produces. Solving this problem does not address the coordination problem described above, and vice versa.

- 15See, e.g., R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377, 391 (1992) (holding as unconstitutional a law that criminalized racially motivated cross-burning on another’s property).

- 16In all law, but constitutional law especially, the line between what the law is and what it should be is sometimes blurred. Laypeople and jurists, including Supreme Court justices, often speak about what the Constitution says, influenced in part by what they think it should say. For example, the view that the Due Process Clause imposes only procedural requirements and does not require that laws conform to some notion of substantive fairness is common among textualists and originalists—who cite the text and intent of the Constitution, which suggest no substantive fairness requirement—despite the fact that substantive due process is now firmly entrenched in constitutional jurisprudence. Likewise, consider how someone might answer the question whether the Second Amendment recognizes an individual right to bear arms. The Supreme Court held in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) that it does; but that question is still hotly debated among legal historians, other jurists, and the public. A person who knows of Heller’s holding but thinks the Court got it wrong might reasonably respond either “No” or “Yes” to the question above.

- 17Russell Hardin theorizes about when people might re-coordinate the constitutional order as a whole. See generally Russell Hardin, Liberalism, Constitutionalism, and Democracy (1999).

- 18Although our survey questions made this explicit, it is possible that some respondents answered the questions based on whether the principle exists in international law generally, without considering whether these legal commitments apply to the United States. For example, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights protects a right to healthcare; but the United States is not a party to this treaty, and Americans are therefore not entitled to the rights it provides. Notably, those respondents who stated that international law protects a right to healthcare might have answered the question for international law in general, not for international law as it applies to the United States.

- 19We randomized whether respondents were first presented with “yes” or with “no” to counter the first-option bias. We also removed participants who took less than 3.5 minutes (half of the median response time) to complete the survey.

- 20See generally American Exceptionalism and Human Rights (Michael Ignatieff ed., 2005).

- 21See Mila Versteeg & Emily Zackin, Constitutions Unentrenched: Toward an Alternative Theory of Constitutional Design,110 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 657, 659–60 (2016).

- 22See David S. Law & Mila Versteeg, The Declining Influence of the United States Constitution, 87 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 762, 854–55 (2012).