Courts’ Limited Ability to Protect Constitutional Rights

Constitutional scholars have generally put faith in courts’ ability to improve the protection of constitutional rights. While courts have limited means to enforce their own decisions, the literature suggests that their decisions are implemented either when courts enjoy strong legitimacy or when they bring functional benefits to other branches. In this Essay, we call this conventional wisdom into question. We present data suggesting that the existence of independent courts does not increase the probability that governments will respect constitutional rights. We outline four reasons why this might be so. First, courts that too frequently obstruct the political branches face court-curbing measures. Second, courts avoid high-profile clashes with the political branches by employing various avoidance canons or deferral techniques. Third, courts protect themselves by issuing decisions that are mostly in line with majoritarian preferences. Finally, courts are ill equipped to deal with certain types of rights violations like torture and social rights. All these accounts offer a potential explanation for why courts’ ability to enforce constitutional rights is more limited than is commonly believed.

Introduction

In October 2015, Poland’s newly elected conservative government moved swiftly to neutralize the country’s Constitutional Tribunal.1 After refusing to swear in the judges appointed by the outgoing government, it amended the Law on the Constitutional Tribunal to alter the court’s quorum requirements for reaching a valid decision. When the constitutional court declared some of these measures unconstitutional, the government simply refused to publish its rulings. By now, the tribunal has fallen fully under the government’s control.

This Polish constitutional blitzkrieg is one of the latest examples of a series of attacks on constitutional courts globally. In 2012, Hungary’s right-wing government adopted a new constitution that both allowed the government to pack the constitutional court with government supporters and stripped the court of many of its powers.2 Around that same time, the Council of Europe received reports of death threats against Romanian judges and attacks on their independence.3 In Georgia, Ukraine, and Kyrgyzstan, new governments stripped the constitutional courts of much of their powers in the early 2000s after those courts had helped to oust their respective authoritarian leaders.4 A decade earlier, the Russian constitutional court lost a series of confrontations with President Boris Yeltsin, leading to a shutdown and reconstitution of the court just two years after it was established.5 Such incidents are not confined to Eastern Europe: similar events have recently occurred in Sri Lanka,6 Egypt,7 Pakistan,8 and Turkey,9 among other countries. Even courts in democracies with a strong tradition of judicial independence are not immune from attacks, as reports from Israel10 and South Africa11 reveal.

These developments are concerning because judges are typically seen as the main “guardians of the constitution”: the ones who ensure that governments will not overstep their powers or encroach on citizens’ rights.12 Indeed, an independent judiciary, equipped with the power of judicial review, has long been touted as critical for the protection of constitutional rights. A common view is that, although the presence of a constitutional right alone may be insufficient to stop governments from later restricting that right, courts provide a way for citizens to validate their rights against the government.13 Courts serve this role primarily by invalidating laws, regulations, and practices that violate constitutions’ rights protections.14 They can also reinterpret laws and regulations so that they do not violate rights and can further award compensation and other remedies to citizens whose rights have been encroached on. Courts, then, are the primary defense mechanism against rights encroachment. Indeed, scholars have celebrated “rights revolutions” simply because courts have started to enforce rights.15 Scholars have further argued that constitutional courts guard democracy itself; they facilitate transitions to democracy by providing insurance to potential political losers16 and protect fragile democracies against one-party rule.17

The faith in courts is widespread not only in the academic literature but also in policy circles. Organizations like the World Bank and US Agency for International Development (USAID) have spent billions of dollars on strengthening judicial independence and capacity around the world, relying, at least in part, on the assumption that functional, independent courts will enforce rights.18 Indeed, the sweeping global expansion of judicial power,19 sometimes characterized as a “judicialization of politics,”20 has generally been met with approval from both scholars and policymakers.

Our research, however, suggests that the presence of independent courts alone might not be enough to stop a government determined to curb its citizens’ rights. As part of a multiyear research project, we have explored, through both quantitative analysis and case studies, whether and how constitutional rights guard against actual rights violations.21 One of the more puzzling findings from our research is that constitutional rights do not appear to be better protected in countries with independent courts equipped with the power of judicial review (which we refer to here as “constitutional courts”).22 While there is a positive correlation between judicial independence and respect for rights in general, we do not find that countries with independent courts are better at upholding their constitutional commitments than countries without such courts.

In trying to make sense of this puzzle, we argue that rights enforcement ultimately falls on citizens themselves. When citizens are organized, they can act strategically to resist rights encroachments through strikes, protests, civil disobedience, and mobilizing the political opposition, as well as litigation. Coordinating such action, however, is not easy and is prone to coordination failure. In earlier work, we have argued that for some rights, it is easier to overcome such collective-action problems because they are practiced by and within formal organizations. 23 This is the case for the right to unionize, which is practiced by trade unions that mobilize for the protection of workers’ rights; for the right to form political parties, which is practiced by political parties that mobilize to protect the right of parties to participate in elections; and for the freedom of religion, which is typically practiced within religious organizations that can take actions to protect religious freedom. Indeed, our statistical analysis reveals that the right to unionize, the right to form political parties, and the freedom of religion are associated with better rights practices.24 Based on case studies in Tunisia, Myanmar, and Russia, we have found evidence that these rights become self-enforcing because of the enforcement actions taken by trade unions, political parties, and religious groups. For individual rights—such as free speech or the prohibition of torture—such enforcement cannot be taken for granted, because mobilization is prone to coordination failure.25

Importantly, when organized groups of citizens mobilize to protect rights, litigation is merely one of the available tools to protect their interests. For example, our case study on religious freedom in Russia reveals that religious groups have mobilized to protect religious freedom by lobbying sympathetic lawmakers, circulating petitions, engaging in public discourse, and organizing education campaigns, in addition to resorting to litigation.26 Courts, then, are merely one of the defense mechanisms against rights encroachments, and perhaps not even the most important one.

Our goal in this Essay is to present some of the global data on the relationship between independent constitutional courts and constitutional-rights enforcement and to set forth some explanations for why courts might be less powerful than is commonly assumed. The remainder of this Essay unfolds as follows. Part I reviews the two main theoretical accounts for how and why courts might be able to enforce rights. Part II presents data suggesting that independent courts do not increase the protection of constitutional rights. The statistical analysis that underlies our ultimate conclusion is available in the Appendix.27 Part III explores limitations inherent in judicial review that may explain why judicial review does not appear to have improved protections of constitutional rights.

I. Theories of Judicial Review: Legitimacy and Functional Benefits

The finding that independent courts are often powerless to enforce the constitution against overbearing governments might come as a surprise to many. When confronted with the puzzle of why political actors would obey the constitution’s constraints on their power, legal scholars and practitioners are often quick to point to the judicial branch.28 The president and Congress will ultimately refrain from taking unconstitutional actions because courts strike down laws and regulations that contradict the constitution, or so the argument goes.

It is not obvious, however, that courts should be successful in enforcing rights against the government. One of the fundamental features of constitutional law is that it lacks an external, super–state enforcement authority capable of coercing political actors to comply with the constitution.29 When it comes to ordinary law—such as codes, statutes, and other rules that apply to private actors within a state—the state is the source of law, and it has power to enforce it against its private subjects.30 In constitutional law, however, the state is not only the source of law, but also its subject, meaning that the only actor empowered to enforce law against the state is the state itself.31

The same is true for judicial decisions enforcing the constitution.32 As Alexander Hamilton famously observed, the judiciary lacks “influence over either the sword or the purse.”33 The judiciary ultimately depends on the executive branch to enforce its rulings. The executive branch may not always be inclined to do so, especially when the executive’s own actions are at issue. To illustrate, consider President Andrew Jackson’s (likely apocryphal) reaction to the Supreme Court’s Worcester v Georgia34 decision: “Well, John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!”35 As this statement illustrates, it is not obvious that governments will respect judicial rulings that curb their power.

There are two main explanations in the literature for how the judiciary can enforce constitutional rights even when the political branches dislike the judicial decision. The first set of explanations—legitimacy theories—holds that courts can do so when they enjoy high levels of legitimacy as an institution. The second set of explanations—functional theories—suggests that independent courts, equipped with the power of judicial review, bring important functional benefits, such as aiding coordination and providing focal points, that outweigh the costs of complying with occasional unfavorable rulings.

A. Legitimacy Theories

A line of research has argued that constitutional court decisions are complied with because of the courts’ legitimacy.36 The idea is that courts can draw on what Professor David Easton called “diffuse support”—that is, “a reservoir of favorable attitudes or good will” toward the institution—“that helps members to accept or tolerate outputs to which they are opposed.”37 High levels of diffuse support, or legitimacy, can mitigate dissatisfaction with unpopular opinions.38 Thus, when a court is perceived as legitimate, its decisions are more likely to be complied with, regardless of the support for the decision itself.

Legitimacy is something that courts build over time. In a study of the high courts of eighteen EU member states, Professors James Gibson, Gregory Caldeira, and Vanessa Baird find that building legitimacy requires gaining support among successive, nonoverlapping constituencies.39 If courts always favored the same groups, however, they would not be perceived as legitimate.40 For example, Professor Heinz Klug has argued that the South African constitutional court’s initial success can be explained by the fact that it favored different constituencies, striking down old apartheid legislation and newer African National Congress (ANC) laws alike.41 Legal scholars have further suggested that legitimacy can be built through legal techniques such as precedent-based reasoning, “investing rhetorical effort in maintaining neutrality,” and carefully crafting decisions so that they appear to be based on legal reasoning alone.42 Courts can further use various techniques to avoid high-profile clashes with the political branches that have the potential to undermine their legitimacy.

Of course, tension may arise from courts’ desire to issue well-reasoned decisions, on one hand, and distributing legal victories evenly, on the other. It is unclear to what extent these two phenomena respectively impact judicial legitimacy. Regardless, the lesson of the legitimacy view is that when stakeholders view the court as the rightful arbiter of constitutional rights, it adds to the court’s reservoir of good will and favorable attitudes. When there is widespread support for the institution as a whole, this increases the likelihood that the government will comply with adverse decisions or else the government itself will lose popularity and may face electoral consequences.

By its nature, legitimacy is usually acquired slowly and easily diminished. A court that frequently appears to disfavor one side—especially when that side is the government—can quickly lose legitimacy. When its legitimacy is depleted, a court may find that decisions that lack specific support are simply not enforced. The court might also witness various other forms of backlash, such as court packing, a change in judicial appointment procedures, or other strategies to curb the court’s independence. We return to this point in Part III.

B. Functional Theories

A second set of explanations focuses on the functional utility of courts. Perhaps the best-known functional theory emphasizes courts’ ability to clarify law and to provide focal points for coordination.43 For example, a well-functioning government needs to coordinate on a set of rules on how to elect the president, how many deputies to elect to parliament, how to divide power between the national government and subnational units, and where to place the capital city.44 While the initial task of coordinating these rules falls on the constitution itself, the judiciary can further aid coordination by clarifying the rules and announcing when political actors have overstepped their powers. Thus, courts supply focal points that increase stability and predictability.45

It is because of the benefits derived from the supply of focal points that governments comply with judicial decisions they do not like. As Professor Russell Hardin notes, supporters of presidential candidate Al Gore ultimately acquiesced in the Bush v Gore46 Supreme Court decision because, even though they (and a majority of the electorate) had chosen Gore, people feared that undermining the Court might foster the sort of political crisis that, in other times and places, has led to unrest, disorder, and even violence.47 Thus, the long-term benefits of having rules by which to play the political game, and the existence of a final arbiter to police these rules, may outweigh the short-term costs of unfavorable decisions.48

Notably, these coordination benefits are more relevant to structural issues than rights, as it is the day-to-day operation of government in which coordination is needed most.49 Constitutional rights, by contrast, do not typically solve coordination problems; this raises the question of whether the coordination-based explanation for compliance extends to judicial decisions that enforce the constitution’s rights provisions.50 Yet, constitution writers do not generally give courts jurisdiction over structure alone. Today, it has become almost unimaginable to draft a constitution that does not include a bill of rights.51 Because political actors value an independent court to interpret the constitution’s structural rules, those actors are also willing to comply with a certain number of rights-related and other rulings that might not serve their short-term interests.52 Although some of those decisions impose costs on the political branches, general compliance is less costly than piecemeal noncompliance, because such ad hoc noncompliance would undermine the courts’ ability to provide valuable clarity on important governance rules.53 This logic suggests that courts might be able to enforce rights at least occasionally, as long as the costs of such decisions do not outweigh the benefits of having a neutral arbiter that supplies focal points.

There are other functional benefits that can flow from having an independent constitutional court. Professor Tamir Moustafa argues that Egyptian President Anwar Sadat created an independent constitutional court to attract foreign investors, and that until recently, the Egyptian government complied with the court’s decisions in order to reap the long-term benefits of foreign investment.54 Similarly, Professor Martin Shapiro notes that the Constitutional Court of Italy owes its success to the fact that it was established as a case-by-case defascification tribunal when the Italian legislature, after World War II, was unable to remove fascist elements from the Italian legal system wholesale.55 It was because of this larger function of the court that the Italian government complied also with those rulings it did not like. Likewise, Professor Tom Ginsburg has suggested that compliance with constitutional decisions occurs because courts are established as a form of political insurance to protect interests of political losers, and those in power are aware that they themselves might need such protection in the future.56 What these accounts share in common is that they emphasize that the functional benefits associated with having a court might outweigh the costs of complying with occasional unfavorable rulings. Regardless of the exact mechanisms, these various accounts suggest that the judiciary might have the power to turn constitutional rights into something more than mere parchment barriers because having a court is valuable to those in power.

Just like legitimacy can be depleted, functional benefits can lose their value. When courts too frequently obstruct the political process, the costs of complying with judicial decisions might outweigh the functional benefits provided by the court. The possibility of backlash is particularly salient when the court issues many unfavorable rulings based on the bill of rights, for which there are fewer coordination benefits to begin with. In such cases, courts may find their jurisdiction stripped or their decisions overturned by constitutional amendment. We also return to this issue in Part III.57

II. Empirical Evidence

Although the legitimacy and functional theories may have appeal, a systematic analysis of the available quantitative data reveals little support for the idea that courts improve compliance with constitutional rights. In this Part, we briefly describe other scholars’ empirical research on the impact of constitutional courts on the protection of constitutional rights and then present some of our own data and empirical results on the subject.

A. Prior Literature

We are not the first to explore the ability of courts to affect constitutional-rights enforcement. Setting aside normative and doctrinal work, which often takes this ability for granted, the question has been addressed in both the qualitative comparative constitutional law literature and in a handful of prior quantitative studies.

The bulk of the comparative constitutional law literature has been quite bullish on the ability of courts to enforce constitutional rights.58 Comparative constitutional scholars have marveled at high-profile human-rights decisions from courts around the world and analyzed such cases extensively in both academic articles and textbooks.59 Two features of the comparative literature are worth noting. First, studies tend to focus on a handful of countries with active and powerful courts, such as Hungary (prior to the rise of the Fidez government), South Africa, Colombia, and India.60 This focus has the potential to skew our impression on courts’ impact. Indeed, cases in which courts have their wings clipped or lack independence entirely are rarely analyzed.61

Second, many of these studies take high-profile constitutional court cases as evidence that constitutional courts are making a difference. One example is Professor Charles Epp’s classic work on rights revolutions. Epp contends that a “rights revolution” has the following conditions: constitutional rights, constitutional courts, rights consciousness, and a legal support structure for mobilization comprising lawyers and organizations that bring cases.62 However, Epp does not inquire whether high-profile judicial decisions actually impact rights on the ground. Many other studies work from the same assumptions.63

Relatively few studies have explored the transformative effect of judicial decisions themselves. The ones that do tend to be less optimistic about courts’ ability to enforce rights than those who treat judicial decisions as the dependent variable. Professor Gerald Rosenberg’s famous study of the ability of US Supreme Court to bring about social change is an illustration.64 Rosenberg shows that, while the US Supreme Court has issued a number of important rights-protecting decisions, many such decisions were ignored or had limited impact. Another important study on social-rights enforcement finds that constitutions’ social-rights provisions are increasingly enforced by courts in Latin America, but that their transformative impact is limited.65 Specifically, based on an in-depth study of Colombia, Professor David Landau finds that judicial enforcement of social rights tends to direct resources toward higher-income groups that can afford to go to court, and thus the decisions fail to improve the lives of the poor.66

There are also a handful of quantitative studies that explore courts’ ability to enforce constitutional rights, although none have explored the question thoroughly. Most of the relevant quantitative empirical literature has focused on the correlation between courts and rights protections generally. More specifically, studies in both economics and political science have found that countries that have independent courts tend to have more respect for rights, including property rights67 and a range of individual rights.68 Economists have further suggested that independent courts can bring about economic growth.69

Only a handful of studies have directly explored courts’ ability to enforce constitutional-rights provisions—rather than to document a general correlation between courts and rights—using quantitative methods. An early study by Professor Frank Cross of a cross section of fifty-three countries found that independent courts did not increase the enforcement of constitutional protections against unreasonable search and seizures.70 In a more comprehensive study, James Melton suggests that constitutional protection of the freedom of expression, association, and movement impact actual respect for these rights in authoritarian regimes with high levels of judicial independence (although there are very few of such regimes).71 Most recently, Charles Crabtree and Professor Michael Nelson have found that the presence of independent courts actually decreases the impact of some constitutional rights and has no significant effect for others.72

Importantly, in none of these papers is the impact of independent judicial review on constitutional-rights enforcement the main object of enquiry. In the remainder of this Part, we will provide an impression of our overall findings by presenting descriptive data. Full results using statistical methods are available in the Appendix.

B. Data

To explore the relationship between judicial review and constitutional-rights enforcement, we first need data on constitutional-rights protections and actual respect for those rights in practice. We focus on nine constitutional rights: (1) the right to unionize (“Unionization”); (2) the right to form political parties (“Political Parties”); (3) the freedom of religion (“Religion”); (4) the right to gender equality (“Gender Equality”); (5) the prohibition of torture (“Torture”); (6) the freedom of expression (“Expression”); (7) the freedom of movement (“Movement”); (8) the right to education (“Education”); (9) the right to healthcare (“Health”). We choose these rights for a combination of substantive and practical reasons. The primary substantive reasons are that we wanted to explore rights that are substantively important, cover a wide range of issue areas, and include a number of different kinds of rights (including both civil and political rights and social and economic rights; and including both rights that are practiced within organizations and rights that are practiced individually). The primary practical reason is that we wanted to focus on rights for which there are time series data on the protection of those rights over time.

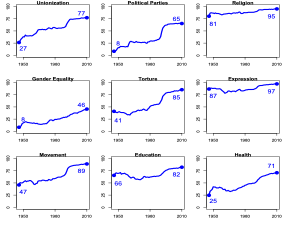

Figure 1 depicts the prevalence of these rights in the world’s constitutions from 1946 to 2010. All twelve rights are more common in 2010 than they were in 1946, but there is considerable variation in the current prevalence of these rights. This ranges from just 46 percent of countries that have a right to gender equality to 97 percent of countries that have a constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression.

Figure 1. Percent of Countries with Rights in Their Constitutions

To explore their impact, we match each of these twelve constitutional rights (de jure rights) to a measure of human-rights outcomes (de facto rights) within the country. These measures, which are based on the annual country reports from Amnesty International and the US State Department, have all been used in prior research on human-rights outcomes, including our own.73 For social rights, our measures of de facto rights variables are measures of social spending by the government. Table 1 lists the dependent variable we use to measure the effectiveness of each of the constitutional rights.

|

De Jure Right |

De Facto Measure |

Source |

|---|---|---|

|

Unionization |

worker: de facto respect for the right to strike/unionize. |

CIRI |

|

Political Parties |

elecsd: de facto respect for right to form political parties. |

CIRI |

|

Religion |

new_relfre: de facto respect for freedom of religion. |

CIRI |

|

Gender Equality |

hgi_ame: Historical Gender Equality Index, which is a composite indicator that includes information on gender inequality in women’s life expectancy, marriage age ratio, seats in parliament, years of schooling, and labor force participation, among other things. |

Dilli, et al (2014) |

|

Torture |

latentmean: latent measure of repression. |

Fariss (2014) |

|

Expression |

speech: de facto respect for freedom of press/expression. |

CIRI |

|

Movement |

dommov: de facto respect for freedom of movement. |

CIRI |

|

Education |

spending_edu: percentage of GDP spent on education. |

World Bank |

|

Health |

spending_health: percentage of GDP spent on healthcare. |

World Bank |

C. Descriptive Exploration

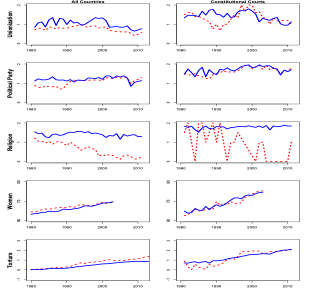

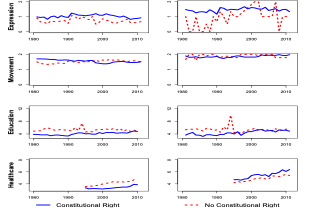

Using these data, we explore whether independent judicial review improves the protection of constitutional rights. In Figure 2, the left panel depicts the average de facto rights measure for countries with and without the right in their constitution. As Figure 2 shows, countries with constitutional rights do not have noticeably better human-rights outcomes. Figure 2 reveals that the freedom of religion might be a noticeable exception. In a more systematic statistical analysis in which we control for a range of confounding factors, we find that religious freedom, the right to form political parties, and the right to unionize, are each associated with better rights practices.74 Interestingly, all these rights are organizational rights, meaning that they are practiced within organizations (organized religion, political parties, and trade unions). In our previous work, we have argued that their organizational character might render them self-enforcing because of the enforcement actions that religious groups, political parties, and trade unions can initiate.75

Figure 2. Effect of Constitutional Rights on Rights Outcomes

We next explore whether this relationship between de jure and de facto rights is different in countries that have an independent judiciary equipped with the power of judicial review (a “Constitutional Court”). The right panel of Figure 2 presents the same graphs, but this time only for countries that have independent constitutional courts. We consider a country to have an independent constitutional court if: (1) the country is coded as having an independent judiciary by the widely used CIRI measure of judicial independence developed by Professors David Cingranelli, David Richards, and K. Chad Clay;76 and (2) we coded the country as having judicial review of its constitution.77 As Figure 2 shows, countries that meet these conditions do not have substantially better rights outcomes than countries that do not meet them. Although there is substantial movement in the lines for countries without constitutional rights and constitutional courts in a few of the graphs, this is largely the case when there are very few countries with constitutional courts without the right (for example, freedom of expression).

Although these results are merely exploratory and do not control for a range of relevant factors that can influence rights outcomes, they provide suggestive evidence that simply having an independent constitutional court does not automatically mean that a constitutional right is more likely to be respected in practice. In the Appendix, we use a range of statistical models and control for confounding factors. In our preferred specifications, reported in Appendix A, we do not find that the interaction between having any of these constitutional rights and an independent constitutional court is positive and statistically significant (the interaction between the freedom of movement and having a court is statistically significant but negative). In some of our robustness checks, we find a few instances of a positive interaction (for religion, torture, and speech), but these are not robust to alternative specifications. In general, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that there is no effect.78

III. Constitutional Courts’ Limitations

How is it possible that courts’ impact on constitutional-rights enforcement is so limited? Both the legitimacy and functional theories suggest important explanations for why court decisions could matter. But they also reveal inherent limitations in the power of judicial review. When a court frequently issues unfavorable rulings against those in power, it may start losing legitimacy or the functional benefits of having an independent court may pale in comparison with their costs. As Professor Shapiro has put it, there exists a tension between judicial lawmaking and judicial independence.79 When judges make law, as inevitably happens in the interpretation of often ambiguous constitutional provisions, they invite attacks on their independence.

This Part explores four explanations for why courts may have limited power to enforce constitutional rights. Specifically, it suggests that: (1) courts may face court-curbing measures; (2) courts employ various doctrinal tools to avoid conflict with the political branches; (3) courts issue decisions largely in line with majoritarian preferences to avoid high-profile clashes with the political branches; and (4) courts are institutionally ill equipped to deal with certain types of rights violations, such as torture and social rights.

A. Court Curbing

When a court is consistently out of step with political coalitions, political actors may retaliate against the court. Such measures are commonly referred to as “court curbing”—that is, “actual changes to the Court’s institutional power—through jurisdiction stripping, court packing, or other legislative means.”80 Such measures can be passed through constitutional reform, legislative measures, or the overturn of long-standing conventions.81 Regardless of the form, their goal is to limit courts’ powers.

Although some have speculated that court-curbing measures are rare because courts will act strategically to avoid them, there are numerous real-world cases. Perhaps the most famous example is President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s court-packing plan. When the US Supreme Court repeatedly struck down legislation during the 1930s, Roosevelt responded with a plan to alter the composition of the court.82 While Roosevelt’s proposal never came to pass, Arizona and Georgia successfully packed their highest courts recently. Exploiting the fact that their state constitutions do not specify how many judges should be on the state supreme court, Republican-controlled legislatures successfully increased the number of judges on their respective supreme courts.83

There are many more recent examples. For instance, the Hungarian Constitutional Court, which struck down roughly one-third of all legislation it reviewed between 1990 and 1995,84 witnessed a range of court-curbing measures after the opposition party gained over two-thirds of the seats in the parliament in 2010.85 The government curbed the court’s power in three ways: (1) by amending the process for nominating constitutional judges as to remove veto power from the opposition parties; (2) by excluding from its jurisdiction many fiscal matters; and (3) by significantly expanding the size of the court, thus allowing Fidesz to appoint rubber-stamp judges.86 It further abolished the actio popularis, which had allowed all citizens to bring a case to court, regardless of whether they were personally affected by the challenged laws or regulations.87 In the Hungarian case, most of these measures were passed through a series of constitutional amendments and the writing of a new constitution.88

In neighboring Poland, the right-wing Law and Justice Party has successfully neutralized the country’s Constitutional Tribunal by amending a series of ordinary laws that change how judges are appointed.89 In Israel, after the supreme court rendered a series of mostly unpopular decisions favoring rights over national security, it saw proposals to restrict its powers and to revise the procedures by which judges are appointed.90 Another recent example is the Constitutional Court of Turkey. The Turkish court has long been a staunch defender of the strong secular protections in the Turkish constitution. To that end, it has banned political parties—including the two previous iterations of the ruling Justice and Development Party91 —and declared amendments to the constitution that would allow the wearing of the headscarf on university campuses to be unconstitutional.92 In response, the Turkish government has resorted to constitutional reforms to alter the power and composition of the court.93 More recently, in the wake of a failed coup attempt, the country has witnessed an all-out assault on judicial independence, and the imprisonment of many judges, including two members of the constitutional court.94

While court curbing might take different forms, in many of these cases political branches retaliated against courts after periods of sustained judicial activism, whereby popular majorities resist judicially imposed constraints on their power. While we lack a systematic record of all attempts at court curbing, these recent attacks on high-profile courts in new democracies suggest that courts that stand in the way of the political branches may have their wings clipped.

B. Judicial Self-Restraint

Courts also have ways to steer clear of high-profile political confrontations in the first place. First, they can employ avoidance doctrines, such as “passive virtues” in the United States95 and the “margin of appreciation” doctrine developed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which allow them to avoid highly charged political questions.96 Second, courts can delay the application of their decisions through the use of deferral techniques to avoid direct clashes with the political branches.97 This technique is commonly used by courts in many countries.98 In our case study on religious freedom in Russia, we found that one of the biggest victories for religious groups came when the constitutional court denied retroactive application of a law that would otherwise have revoked the registration of new religious groups.99 In this case, the Constitutional Court of Russia did not declare the law to be unconstitutional, but rather interpreted it to neutralize its most harmful effects. In the same vein, Professors Yonatan Lupu, Pierre Verdier, and Mila Versteeg show that national courts are more successful in enforcing the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) when they interpret domestic laws in line with the ICCPR than when they strike these laws entirely, exactly because the former allows courts to avoid high-profile political confrontations.100

These various forms of self-restraint may allow courts to build legitimacy so that they can occasionally spend their political capital on a particularly egregious violation. In some cases, such self-restraint is built into the constitution. Professor Stephen Gardbaum argued in favor of “weak-form” judicial review, such as the notwithstanding mechanism in Canada, whereby the legislature has the ability to override judicial rulings.101 According to Gardbaum, weak-form judicial review produces fruitful dialogue between the political and judicial branches, but ultimately leaves the final word on the constitution to the political branches, thereby preserving the long-term independence of the courts.102 He suggests that such weak forms are particularly desirable in new democracies that do not have a long tradition of judicial independence. Professor Mark Tushnet has similarly suggested that weak forms of judicial review are desirable in the enforcement of social rights, which is inherently more political in nature.103 In these cases, constitutional designers shelter courts from high-profile clashes with the political branches by giving the political branches the final say on the constitution.

While these various techniques can ensure the independence of courts in the longer run, their usage implies that courts, in many cases, will steer clear from rendering high-profile decisions that enforce constitutional rights.

C. The Majoritarian Character of Courts

Instead of employing doctrinal tools to avoid certain questions, courts can also decide to issue rulings that are largely in line with the preferences of the political branches. Indeed, a large body of research implies that courts alter their behavior strategically in response to their broader political environment.104 Scholars of the US Supreme Court have long observed that the Court rarely issues decisions that are truly countermajoritarian in nature. As early as the 1950s, Professor Robert Dahl observed that “the policy views dominant on the Court are never for long out of line with the policy views dominant among the lawmaking majorities of the United States.”105 Although the justices themselves commonly claim that popular opinion should not affect judicial interpretation,106 many have observed that judicial decisionmaking tends to align with political preferences at the national level.107 Importantly, if judicial decisions reflect the preferences of popular majorities, we should not expect them to issue decisions about constitutional rights that are truly countermajoritarian in nature. By contrast, they may be more likely to rule against a small group that attempts to repress large parts of the population. This, indeed, was exactly James Madison’s insight when he suggested bills of rights are better suited to protect against the problem of minorities taking advantage of the majority108 than against rights violations by majorities against minorities.109

There are different explanations for why court rulings are often majoritarian in nature. One is the possibility of court curbing. A body of political science literature has postulated “that periods of Court curbing are followed by marked periods of judicial deference to legislative preferences.”110 Indeed, Roosevelt’s court-packing plan famously produced Justice Owen Roberts’s “switch in time” and brought the Supreme Court in line with popular preferences.111 Building on this insight, Professors Lee Epstein, Jack Knight, and Olga Shvetsova suggest that courts should stay within the “tolerance intervals” of the political branches in order to avoid attacks on their independence.112 Over time, the size of the tolerance intervals might increase as the court builds legitimacy; until then, courts are better off staying within the “safe areas, or else they will face political backlash.113 Epstein, Knight, and Shvetsova illustrate this point by analyzing the case law of the ill-fated first Russian constitutional court, which was suspended by President Yeltsin in 1993, a mere two years after its inception. They show that this court decided a number of highly charged political disputes before it had built up a reservoir of good will, and offer this as an explanation for its early demise.114

A second explanation for why courts rule in line with popular preferences is the knowledge that unpopular decisions might be overturned or simply remain unimplemented. Scholars of the US Supreme Court have theorized that when judicial decisions can be overturned through legislation, courts will pick their preferred policy from those policy options that are unlikely to be overturned.115 Presumably, the same logic applies to constitutional amendments, whereby courts try to avoid decisions that will likely result in constitutional amendments, especially in those countries for which constitutions are relatively easy to amend. For example, when the Indian Supreme Court struck down land reform laws in the name of private property in the 1960s and 1970s, it saw relentless pressure from the legislature, which kept overturning the court’s decisions through constitutional amendment, until the court switched its position.116 In the German context, Professor Georg Vanberg has found that German judges take the policy preferences of political actors into account, because “they must often rely on legislative majorities to abide by, and sometimes even to carry out, their decisions.”117

Finally, courts may rule in line with political branches because they share the preferences of those who appointed them. That is, even when courts are fully independent, judges are typically appointed and confirmed by the political branches, who often appoint judges who share their preferences. This likely has a moderating effect on courts’ desire to stand up against the political branches, especially as long as the party that appointed them remains in power. What is more, in a context in which courts are not independent, courts can simply become agents of the executive. To illustrate, the Venezuelan Supreme Court recently issued a ruling that assigned the congress’s power to the court itself, thereby effectively stifling opposition against the executive.118 In this scenario, we can no longer view the court as enforcing majoritarian preferences (the congress, after all, was democratically elected); rather, it is acting as an agent of the executive that appointed the court. While our analysis in this Essay focuses on courts that are considered to be independent, it is worth observing that, in many parts of the world, courts lack independence entirely.

D. Institutional Limitations

Courts are also institutionally ill equipped to deal with certain types of rights violations. Importantly, courts are unable to continuously monitor behavior, and instead depend on certain cases to reach the court. One type of rights violation that is unlikely to reach the court is torture. Torture tends to take place in secret, behind closed doors, and in violation of existing legal norms. Although there are occasional attempts to create a legal space for torture—as in the infamous US torture memos119 —torture is usually an extralegal affair.120 Thus, constitutional courts are unlikely to be presented with laws or regulations that legalize torture and can be struck down. Moreover, the lack of information on torture further hurts courts’ ability to award individual remedies for torture victims.121 The prohibition of torture, therefore, might be particularly hard to enforce.

Some have suggested that courts are also institutionally ill equipped to enforce social rights, such as the right to education or the right to healthcare.122 Enforcing these rights requires courts to make decisions that are essentially political in nature, as they involve the allocation of scarce funds.123 Courts have found various ways around such limitations. The South African Constitutional Court famously defers to the political branches when it comes to social rights; it merely requires the government to have a reasonable policy in place without dictating the substance of this policy.124 Many other courts have focused relief for individual plaintiffs, without ordering systematic remedies that would affect larger groups of people.125 The Colombian Constitutional Court’s tutelas that have ordered the government to pay for individual’s health treatments, pensions, or provide other subsidies, fit this “individualized enforcement” model.126 Finally, some courts have interpreted social rights as a nonretrogression principle, meaning that they have stricken austerity measures and other rules and regulations that reduce social benefits.127 Such “negative injunctions” have been employed in Brazil, Hungary, and Argentina, among other countries.128 The flipside of these various approaches is that courts have only very rarely ordered system-wide reforms to transform social justice. What is more, some studies have observed that the individualized enforcement model, which is the most common in many countries, might come at the expense of social mobilization.129 Rather than organizing and mobilizing to persuade the government to provide social rights, individuals might simply go to court to ensure the delivery of certain services to themselves. If social mobilization is indeed the key to rights enforcement, as we suggest elsewhere, then judicial enforcement could hamper the implementation of social rights.130

Conclusion

The data we presented suggest that constitutional courts are less impactful than is commonly believed. Of course, our findings leave many questions unanswered. Probably the most pressing among them is: If not primarily through constitutional courts, how should we enforce constitutional rights?

We have argued elsewhere that constitutional-rights provisions need to be self-enforcing to be effective. That is, they need to be supplemented by protective constituencies that have a stake in preserving these rights and that can make it costly for a government to violate rights.131 Such protective constituencies include trade unions, organized religion, and political parties. For such groups, litigation is an important tool, but not the only one. They can also organize protests, mobilize the political opposition, organize petitions, educate the public, and engage in acts of civil disobedience.

Indeed, one possibility raised by our analysis is that the enforcement of judicial decisions itself depends on the existence of protective constituencies. There is some support for this conjecture in the literature. For example, scholars of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights have observed that the court’s rulings are more likely to be implemented when there are groups that mobilize for their implementation.132 Similarly, it has been observed that the South African Constitutional Court’s famous Republic of South Africa v Grootboom133 decision on the right to housing was never fully implemented, while its Minister of Health v Treatment Action Campaign134 decision on antiviral HIV/AIDS drugs did get implemented. This difference has been attributed to the fact that there were no committed groups to follow up on the Grootboom decision, while the Treatment Action Campaign, an NGO committed to provision of HIV/AIDS medication, did push for implementation and created a broader social movement around the decision.135

The existence of civil-society groups that push for implementation, then, might be key to courts’ effectively enforcing the constitution. There are other possible factors that could impact the extent to which judicial enforcement of constitutional rights is effective. It is possible that some subset of courts may be better able to protect rights—for example, those situated in long-standing democracies or countries with respect for the rule of law. One important task for future research is to discover under what conditions independent courts are most impactful and the possible drivers of their success.

Appendix

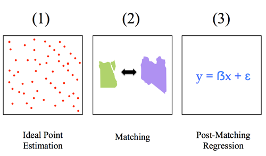

Our primary statistical analysis uses the three-step research design depicted in Figure A.136 In Step 1, we first calculate the probability a country would have a specific right within its constitution. To do so, we use a matrix of eighty-seven possible constitutional rights to calculate a constitutional “ideal point” for each country in each year. We then are able to calculate the probability a country would have a given constitutional right.

In Step 2, we match country-year observations that have a given constitutional right to other country-year observations that do not have the specific right. Our matching algorithm uses the ideal point estimates from Step 1, along with the “standard” variables used in the human-rights literature.

In Step 3, we run regressions on the matched datasets. These regressions include variables for whether a country has a given constitutional right and all of the variables included in the matching process. We also include an interaction term between the variables “Constitutional Right” and “Constitutional Court.” This is our variable of interest.

Figure A. Three-Step Research Design

This Appendix presents three versions of our results. In Section A, we present the results using the process described above. In Section B, we present results without preprocessing our data with matching (in other words, we skip Step 2). In Section C, we present results without preprocessing our data with matching while also including country fixed effects. Although we find a positive and statistically significant interaction effect in a couple of specifications, this is not consistent across specifications for a single right. In other words, we do not find consistent evidence that an independent judiciary, equipped with the power of judicial review, is able to strengthen the enforcement of constitutional rights.

A. Baseline Results

| Organizational Rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unionization | Political Parties | Religion | |

| Constitutional Right | 0.815*** (0.252) |

0.652*** (0.244) |

1.080**(0.423) |

| Constitutional Court | 0.148 (0.831) |

–0.370 (0.616) |

— |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –0.405 (0.941) |

0.386 (0.709) |

0.962 (0.632) |

| Probability of Right | –0.605* (0.341) |

0.558 (0.347) |

0.056 (0.923) |

| Polity | 0.124*** (0.341) |

0.263*** (0.035) |

0.052 (0.047) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 0.223* (0.134) |

0.223 (0.146) |

–0.267 (0.254) |

| Population (ln) | –0.270*** (0.087) |

0.062 (0.085) |

–0.331*** (0.112) |

| Interstate War | –0.127 (0.489) |

–0.446 (0.379) |

0.156 (0.386) |

| Civil War | 0.282 (0.468) |

–0.499 (0.468) |

–0.379 (0.672) |

| Civil Society | 3.023*** (0.809) |

2.901*** (0.540) |

3.276*** (1.212) |

| Regime Durability | 0.008* (0.004) |

0.014*** (0.006) |

0.014* (0.008) |

| Youth Bulge | –0.014 (0.022) |

–0.008 (0.030) |

–0.056 (0.044) |

| Observations | 1,426 | 1,390 | 482 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant and year fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table. A variable is omitted because it is collinear with the interactional between Constitutional Court and Constitutional Right.

| Individual Rights | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Equality | Torture | Expression | Movement | |

| Constitutional Right | –0.781 (1.046) |

–0.288* (0.160) |

0.236 (0.537) |

0.252 (0.344) |

| Constitutional Court | –1.721 (2.681) |

–0.247 (0.238) |

— | 13.946*** (0.913) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –1.761 (3.034) |

0.481 (0.293) |

–1.603 (2.114) |

–13.066*** (1.090) |

| Probability of Right | 4.260*** (1.591) |

–0.114 (0.168) |

–0.198 (1.059) |

0.493 (0.380) |

| Polity | 0.357*** (0.108) |

0.028* (0.016) |

0.151 (0.097) |

0.224*** (0.048) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | –0.445 (0.637) |

0.197** (0.076) |

–0.025 (0.273) |

0.678*** (0.176) |

| Population (ln) | –0.792 (0.501) |

–0.239*** (0.061) |

–0.085 (0.209) |

–0.766*** (0.126) |

| Interstate War | 0.320 (1.164) |

–1.009*** (0.192) |

0.453 (0.677) |

–0.574 (0.419) |

| Civil War | –1.054 (1.281) |

–0.472*** (0.171) |

–0.445 (0.479) |

0.409 (0.666) |

| Civil Society | 0.442 (2.230) |

1.429*** (0.335) |

4.236*** (1.165) |

0.199 (0.976) |

| Regime Durability | 0.016 (0.018) |

0.007** (0.003) |

0.007 (0.014) |

–0.010 (0.007) |

| Youth Bulge | –0.604*** (0.133) |

–0.048*** (0.015) |

–0.119* (0.063) |

0.060* (0.032) |

| Observations | 954 | 1,126 | 204 | 812 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant and year fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table. A variable is omitted because it is collinear with the interactional between Constitutional Court and Constitutional Right.

| Socioeconomic Rights | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education | Healthcare | |

| Constitutional Right | –0.002 (0.113) |

–0.026 (0.065) |

| Constitutional Court | –0.125 (0.250) |

0.352 (0.564) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | 0.007 (0.325) |

–0.465 (0.560) |

| Probability of Right | –0.075 (0.112) |

–0.004 (0.098) |

| Polity | 0.026*** (0.009) |

0.011 (0.007) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 0.189*** (0.069) |

0.107 (0.074) |

| Interstate War | 0.330 (0.234) |

–0.197 (0.125) |

| Civil War | –0.837 (0.575) |

–0.005 (0.123) |

| Urban Population | –0.008*** (0.003) |

–0.001 (0.002) |

| Population over 65 | –0.010 (0.013) |

0.037** (0.015) |

| Inflation | –0.002*** (0.001) |

–0.000*** (0.000) |

| GDP Growth | –0.029*** (0.010) |

–0.011*** (0.003) |

| Spending t–1 | 0.899*** (0.031) |

0.833*** (0.075) |

| Observations | 188 | 472 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant and year fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

B. Without Matching

| Organizational Rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unionization | Political Parties | Religion | |

| Constitutional Right | 0.919*** (0.276) |

0.431** (0.201) |

1.383*** (0.459) |

| Constitutional Court | 0.880* (0.462) |

0.515** (0.254) |

–0.719 (0.619) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –0.501 (0.490) |

–0.048 (0.312) |

1.460** (0.648) |

| Probability of Right | –0.409 (0.306) |

0.236 (0.253) |

–0.800 (0.834) |

| Polity | 0.090*** (0.020) |

0.229*** (0.022) |

0.066*** (0.022) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 0.036 (0.095) |

0.177* (0.090) |

0.091 (0.095) |

| Population (ln) | –0.176*** (0.058) |

–0.018 (0.049) |

–0.269*** (0.057) |

| Interstate War | –0.230 (0.332) |

–0.143 (0.272) |

0.031 (0.268) |

| Civil War | –0.239 (0.301) |

–0.552 (0.497) |

–0.577* (0.350) |

| Civil Society | 3.065*** (0.471) |

2.572*** (0.472) |

3.146*** (0.458) |

| Regime Durability | 0.003 (0.004) |

0.012*** (0.003) |

0.009*** (0.003) |

| Youth Bulge | –0.038*** (0.014) |

–0.003 (0.016) |

0.059*** (0.016) |

| Observations | 4,763 | 4,763 | 5,309 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant and year fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

| Individual Rights | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Equality | Torture | Expression | Movement | |

| Constitutional Right | –0.498 (1.024) |

–0.394** (0.166) |

–0.042 (0.324) |

–0.038 (0.350) |

| Constitutional Court | –2.230 (1.484) |

–0.263 (0.225) |

–1.521 (0.928) |

0.405 (0.726) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | 1.230 (1.641) |

0.537** (0.226) |

1.874** (0.947) |

–0.029 (0.767) |

| Probability of Right | 3.830*** (1.215) |

–0.098 (0.163) |

0.198 (0.614) |

0.178 (0.341) |

| Polity | 0.251*** (0.094) |

0.007 (0.011) |

0.138*** (0.018) |

0.132*** (0.025) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 0.108 (0.521) |

0.329*** (0.059) |

0.271*** (0.084) |

0.414*** (0.138) |

| Population (ln) | –0.679** (0.331) |

–0.146*** (0.031) |

–0.120** (0.051) |

–0.184** (0.072) |

| Interstate War | –0.168 (0.838) |

–1.031*** (0.145) |

0.082 (0.190) |

–0.521* (0.295) |

| Civil War | –1.560* (0.911) |

–0.540*** (0.130) |

–0.434 (0.361) |

–0.231 (0.513) |

| Civil Society | 0.547 (2.102) |

1.493*** (0.240) |

3.575*** (0.426) |

1.225** (0.517) |

| Regime Durability | 0.025** (0.012) |

0.007*** (0.003) |

0.006 (0.004) |

0.006 (0.005) |

| Youth Bulge | –0.437*** (0.080) |

–0.016** (0.008) |

0.011 (0.015) |

0.017 (0.016) |

| Observations | 2,679 | 5,255 | 4,763 | 5,315 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant and year fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

| Socioeconomic Rights | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education | Healthcare | |

| Constitutional Right | 0.069 (0.058) |

0.006 (0.038) |

| Constitutional Cour | 0.036 (0.065) |

0.010 (0.052) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –0.065 (0.068) |

0.065 (0.071) |

| Probability of Right | –0.046 (0.044) |

–0.076* (0.041) |

| Polity | 0.001 (0.003) |

0.003 (0.002) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 0.058** (0.028) |

0.016 (0.023) |

| Interstate War | –0.007 (0.061) |

–0.028 (0.050) |

| Civil War | –0.074 (0.082) |

–0.060 (0.046) |

| Urban Population | –0.001 (0.001) |

–0.001 (0.001) |

| Population over 65 | –0.003 (0.004) |

0.016*** (0.004) |

| Inflation | –0.000* (0.000) |

–0.000** (0.000) |

| GDP Growth | –0.009** (0.004) |

–0.012*** (0.004) |

| Spending t–1 | 0.946*** (0.013) |

0.937*** (0.020) |

| Observations | 1,967 | 2,885 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant and year fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

C. Without Matching + Country Fixed Effects

| Organizational Rights | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unionization | Political Parties | Religion | |

| Constitutional Right | 0.287*** (0.083) |

0.092 (0.057) |

0.550*** (0.132) |

| Constitutional Court | 0.230*** (0.087) |

0.156*** (0.059) |

0.013 (0.147) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –0.096 (0.104) |

0.002 (0.078) |

0.170 (0.152) |

| Probability of Right | 0.175* (0.103) |

0.229*** (0.061) |

–0.429*** (0.116) |

| Polity | 0.006 (0.007) |

0.048*** (0.005) |

0.016*** (0.006) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | –0.002 (0.024) |

0.024 (0.025) |

–0.011 (0.024) |

| Population (ln) | –0.018* (0.010) |

0.009 (0.012) |

0.010 (0.009) |

| Interstate War | 0.026 (0.073) |

–0.102 (0.062) |

–0.015 (0.079) |

| Civil War | 0.009 (0.063) |

–0.041 (0.072) |

0.087 (0.095) |

| Civil Society | 0.579*** (0.148) |

0.404*** (0.099) |

0.485*** (0.124) |

| Regime Durability | –0.002 (0.001) |

0.001 (0.001) |

–0.000 (0.001) |

| Youth Bulge | 0.004 (0.005) |

0.001 (0.004) |

–0.001 (0.004) |

| Observations | 4,763 | 4,763 | 5,309 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant, year fixed effects, and country fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

| Individual Rights | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Equality | Torture | Expression | Movement | |

| Constitutional Right | 0.761 (0.595) |

–0.230* (0.133) |

0.159 (0.169) |

0.142 (0.172) |

| Constitutional Court | 0.504 (0.513) |

–0.032 (0.140) |

0.095 (0.095) |

0.150** (0.075) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –0.317 (0.625) |

0.264* (0.157) |

0.009 (0.104) |

–0.067 (0.091) |

| Probability of Right | 4.286*** (1.296) |

0.163 (0.122) |

0.016 (0.156) |

–0.025 (0.135) |

| Polity | –0.016 (0.061) |

0.021*** (0.008) |

0.030*** (0.005) |

0.016** (0.007) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 1.252** (0.528) |

0.025 (0.030) |

0.014 (0.021) |

0.031 (0.030) |

| Population (ln) | 0.163 (0.328) |

0.011 (0.014) |

–0.003 (0.011) |

–0.017 (0.015) |

| Interstate War | –0.809 (0.500) |

–0.413*** (0.120) |

–0.046 (0.047) |

–0.125* (0.075) |

| Civil War | –0.138 (0.506) |

–0.104 (0.108) |

–0.015 (0.063) |

0.027 (0.143) |

| Civil Society | –1.692 (1.053) |

0.623*** (0.157) |

0.429*** (0.110) |

0.256 (0.170) |

| Regime Durability | 0.011 (0.023) |

0.004*** (0.001) |

0.001 (0.001) |

0.000 (0.002) |

| Youth Bulge | –0.058 (0.059) |

–0.006 (0.006) |

–0.004 (0.004) |

–0.008 (0.005) |

| Observations | 2,679 | 5,255 | 4,763 | 5,315 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant, year fixed effects, and country fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

| Socioeconomic Rights | ||

|---|---|---|

| Education | Healthcare | |

| Constitutional Right | 0.144 (0.126) |

0.460** (0.215) |

| Constitutional Court | 0.142 (0.134) |

0.148 (0.113) |

| Constitutional Right x Constitutional Court | –0.158 (0.138) |

–0.030 (0.137) |

| Probability of Right | –0.148 (0.141) |

–0.504 (0.309) |

| Polity | 0.010 (0.007) |

0.003 (0.008) |

| GDP per Capita (ln) | 0.094* (0.049) |

0.040 (0.035) |

| Interstate War | 0.113 (0.106) |

0.038 (0.078) |

| Civil War | 0.014 (0.099) |

0.052 (0.092) |

| Urban Population | 0.011 (0.007) |

–0.000 (0.008) |

| Population over 65 | –0.018 (0.019) |

0.030 (0.027) |

| Inflation | –0.000*** (0.000) |

–0.000 (0.000) |

| GDP Growth | –0.013*** (0.005) |

–0.014*** (0.005) |

| Spending t–1 | 0.770*** (0.025) |

0.644*** (0.060) |

| Observations | 1,967 | 2,885 |

Note: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1. Robust standard errors are clustered by country in parentheses. All specifications included a constant, year fixed effects, and country fixed effects; however, we omit them from the table.

- 1See Tomasz Tadeusz Koncewicz, Polish Constitutional Drama: Of Courts, Democracy, Constitutional Shenanigans and Constitutional Self-Defense (I×CONnect, Dec 6, 2015), archived at http://perma.cc/JC8P-QYTG. See also Joanna Fomina and Jacek Kucharczyk, Populism and Protest in Poland, 27 J Democracy 58, 62–63 (Oct 2016).

- 2See Stephen Gardbaum, Are Strong Constitutional Courts Always a Good Thing for New Democracies?, 53 Colum J Transnatl L 285, 295–97 (2015).

- 3See Neil Buckley, Judges Caught in Romania Power Struggle (Fin Times, Aug 7, 2012), online at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/113332a2-e0af-11e1-8d0f-00144feab49a.html#axzz40TxNtdGl (visited Aug 29, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable).

- 4See Alexei Trochev, Fragmentation? Defection? Legitimacy? Explaining Judicial Roles in Post-Communist “Colored Revolutions,” in Diana Kapiszewski, Gordon Silverstein, and Robert A. Kagan, eds, Consequential Courts: Judicial Roles in Global Perspective 67, 67–68 (Cambridge 2013).

- 5See Lee Epstein, Jack Knight, and Olga Shvetsova, The Role of Constitutional Courts in the Establishment and Maintenance of Democratic Systems of Government, 35 L & Society Rev 117, 135–37 (2001).

- 6For example, in November 2012, the Sri Lankan parliament successfully impeached the chief justice of the supreme court after the court held that various parts of a government’s controversial bill were inconsistent with the constitution. Accused of misuse of power, the chief justice was removed from her office by the Sri Lankan president who ignored a court of appeals’ decision finding the impeachment process illegal. Other judges received threatening phone calls. See Sri Lanka: New Chief Justice Sworn In (NY Times, Jan 15, 2013), online at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/16/world/asia/sri-lanka-new-chief-justice-sworn-in.html (visited Dec 13, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable); Sri Lanka Ruling Party MPs Move to Impeach Top Judge (Express Trib, Nov 1, 2012), archived at http://perma.cc/46ZM-KNEQ; Hafeel Farisz and Dasun Rajapakshe, Appeal Court Judges Get Threatening Calls (Daily Mirror, Jan 8, 2013), archived at http://perma.cc/F4TB-TW7K.

- 7In August 2012, in Egypt, the newly approved constitution reduced the size of the Supreme Constitutional Court from nineteen to eleven members, retaining the ten longest serving members and the chief justice. This was widely viewed as a political move to remove the anti–Muslim Brotherhood justices, including the court’s only female member. See Jeffrey Fleishman and Reem Abdellatif, Egypt President Mohamed Morsi Expands Authority in Power Grab (LA Times, Nov 22, 2012), archived at http://perma.cc/6ALA-43CF; Liliana Mihaila, Why the Reduction in SCC Justices? (Daily News Egypt, Dec 24, 2012), online at http://dailynewsegypt.com/2012/12/24/why-the-reduction-in-scc-justices/ (visited Dec 13, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable).

- 8In the mid- to late 1990’s, after repeated clashes between Pakistan’s government and the supreme court, then–Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto “aggressively sought to pack the courts with judges regarded as loyal to her party’s interests—ignoring basic rules concerning qualifications for appointment and seniority-based conventions for elevating judges, and further manipulating judicial composition by appointing ad hoc judges and transferring judges between courts.” Anil Kalhan, “Gray Zone” Constitutionalism and the Dilemma of Judicial Independence in Pakistan, 46 Vand J Transnatl L 1, 40 (2013). The current Pakistani prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, “proved no less aggressive, clashing with the Supreme Court over appointments and other issues and later engaging in an ugly effort to remove the chief justice, which culminated in a physical attack on the Supreme Court building by a mob of Sharif’s supporters.” Id.

- 9See Gulsen Solaker, Turkish Judge Defies Erdogan with Attack on ‘Dire’ Allegations (Reuters, Apr 25, 2014), archived at http://perma.cc/8N3V-6W4Q (describing the conflict between then–Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the constitutional court).

- 10See Jonathan Lis, Kulanu Balks at Likud Demand to Weaken Israel’s Supreme Court (Haaretz, Apr 21, 2015), online at http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-1.652811 (visited Oct 5, 2017) (Perma archive unavailable) (describing recent attempts by the government to reduce the supreme court’s power and change the court’s appointment mechanism).

- 11See Gardbaum, 53 Colum J Transnatl L at 298 (cited in note 2) (noting that President Jacob Zuma described some of the constitutional court’s judges as “counter revolutionaries” and has asked for a review of the court’s power and an evaluation of whether the court has stood in the way of socioeconomic transformation).

- 12See Carl Schmitt, The Guardian of the Constitution ch I.1–3, in Lars Vinx, ed, The Guardian of the Constitution: Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the Limits of Constitutional Law 79, 79–90 (Cambridge 2015) (Lars Vinx, trans).

- 13See, for example, Stephen Holmes, Precommitment and the Paradox of Democracy, in Jon Elster and Rune Slagstad, eds, Constitutionalism and Democracy: Studies in Rationality and Social Change 195, 236–37 (Cambridge 1988); Daniel A. Farber, Rights as Signals, 31 J Legal Stud 83, 92–93 (2002).

- 14See Richard H. Fallon Jr, The Core of an Uneasy Case for Judicial Review, 121 Harv L Rev 1693, 1728–31 (2008).

- 15See, for example, Charles R. Epp, The Rights Revolution: Lawyers, Activists, and Supreme Courts in Comparative Perspective 7–8 (Chicago 1998) (noting that a “rights revolution” consists of “judicial attention to the new rights, judicial support for the new rights, and implementation of the new rights” whereas implementation is “the extent to which courts have issued a continuing stream of judicial decisions that enforce or elaborate on earlier decisions”); David R. Boyd, The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment 7 (UBC 2012) (“Because of the prominent role of courts in this process, the rights revolution is closely tied to constitutionalism and the judicialization of politics.”).

- 16See Tom Ginsburg, Judicial Review in New Democracies: Constitutional Courts in Asian Cases 21–33 (Cambridge 2003) (“By ensuring that losers in the legislative arena will be able to bring claims to court, judicial review lowers the cost of constitution making and allows drafters to conclude constitutional bargains that would otherwise be unobtainable.”).

- 17See Samuel Issacharoff, Fragile Democracies: Contested Power in the Era of Constitutional Courts 132–36 (Cambridge 2015).

- 18See, for example, David M. Trubek, The “Rule of Law” in Development Assistance: Past, Present, and Future, in David M. Trubek and Alvaro Santos, eds, The New Law and Economic Development: A Critical Appraisal 74, 74 (Cambridge 2006) (noting that the World Bank has spent $2.9 billion on rule-of-law reforms since 1990).

- 19See Ran Hirschl, Towards Juristocracy: The Origins and Consequences of the New Constitutionalism 1–3 (Harvard 2004) (describing the judicial empowerment that resulted from the “sweeping worldwide convergence to constitutionalism”).

- 20See C. Neal Tate and Torbjörn Vallinder, The Global Expansion of Judicial Power: The Judicialization of Politics, in C. Neal Tate and Torbjörn Vallinder, eds, The Global Expansion of Judicial Power 1, 5–6 (NYU 1995).

- 21See generally Adam S. Chilton and Mila Versteeg, Do Constitutional Rights Make a Difference?, 60 Am J Polit Sci 575 (2016); Adam S. Chilton and Mila Versteeg, The Failure of Constitutional Torture Prohibitions, 44 J Legal Stud 417 (2015); Adam S. Chilton and Mila Versteeg, International Law, Constitutional Law, and Public Support for Torture, 3 Rsrch & Polit 1 (Jan–Mar 2016); Adam S. Chilton and Mila Versteeg, Rights without Resources: The Impact of Constitutional Social Rights on Social Spending, J L & Econ (forthcoming), archived at http://perma.cc/VV7C-TTGV; Adam S. Chilton, Maria Smirnova, and Mila Versteeg, Constitutional Rights in Action; a Case Study on Religious Freedom in Russia (unpublished manuscript).

- 22See, for example, Chilton and Versteeg, 60 Am J Polit Sci at 584–85 (cited in note 21).

- 23See id.

- 24See id at 582–84.

- 25See id.

- 26Chilton, Smirnova, and Versteeg, Constitutional Rights in Action (cited in note 21).

- 27Similar results will further feature in our forthcoming book manuscript and have partly been featured in our peer-reviewed publications.

- 28See Jack Goldsmith and Daryl Levinson, Law for States: International Law, Constitutional Law, Public Law, 122 Harv L Rev 1791, 1830–31 (2009) (observing that constitutional scholars rarely ask why the constitution is complied with, and that “[w]hen such questions are raised . . . the answers tend to begin and end with judicial review”).

- 29See id at 1795. See also Gillian K. Hadfield and Barry R. Weingast, Constitutions as Coordinating Devices, in Sebastian Galiani and Itai Sened, eds, Institutions, Property Rights, and Economic Growth: The Legacy of Douglass North 121, 122 (Cambridge 2014); Russell Hardin, Why a Constitution? (“Why a Constitution? (2013)”), in Denis J. Galligan and Mila Versteeg, eds, Social and Political Foundations of Constitutions 51, 53, 65–66 (Cambridge 2013); Daryl J. Levinson, Parchment and Politics: The Positive Puzzle of Constitutional Commitment, 124 Harv L Rev 657, 662 (2011); Martin Shapiro, The European Court of Justice: Of Institutions and Democracy, 32 Isr L Rev 3, 8 (1998).

- 30See Goldsmith and Levinson, 122 Harv L Rev at 1795–96 (cited in note 28).

- 31See John Austin, The Province of Jurisprudence Determined 364 (Legal Classics 1984) (originally published 1832) (noting that “without men to enforce them,” constitutions are “merely idle words scribbled on paper or parchment”); Frederick Schauer, The Force of Law 89–92 (Harvard 2015).

- 32See Dieter Grimm, Judicial Activism, in Robert Badinter and Stephen Breyer, eds, Judges in Contemporary Democracy: An International Conversation 17, 26 (NYU 2004) (“It is the specific weakness of constitutional courts that the power is in the hands of those who are affected by their decisions.”).

- 33Federalist 78 (Hamilton), in The Federalist 521, 522–23 (Wesleyan 1961) (Jacob E. Cooke, ed) (deeming the judiciary the “least dangerous” branch).

- 3431 US 515 (1832).

- 35See Richard H. McAdams, The Expressive Powers of Law: Theories and Limits 58 (Harvard 2015).

- 36See, for example, David Easton, A Systems Analysis of Political Life 267–68 (Chicago 1979); David Easton, A Re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support, 5 British J Polit Sci 435, 450–53 (1975); James L. Gibson and Gregory A. Caldeira, The Legitimacy of Transnational Legal Institutions: Compliance, Support, and the European Court of Justice, 39 Am J Polit Sci 459, 461 (1995); James L. Gibson, Gregory A. Caldeira, and Vanessa A. Baird, On the Legitimacy of National High Courts, 92 Am Polit Sci Rev 343, 344–46 (1998); Richard H. Fallon Jr, Legitimacy and the Constitution, 118 Harv L Rev 1787, 1794–96 (2005). Recent work by Professors Tom Ginsburg and Nuno Garoupa conceptualizes some of these same ideas as judicial reputation. See Nuno Garoupa and Tom Ginsburg, Judicial Reputation: A Comparative Theory 14–23 (Chicago 2015). There is a related strand of research, tracing back to Max Weber, that deals with the legitimacy of law more broadly, which we set aside here. There is also a strand of legitimacy theory that is more normative in character. See generally, for example, Daniel Bodansky, The Legitimacy of International Governance: A Coming Challenge for International Environmental Law?, 93 Am J Intl L 596 (1999). There are also studies focused on procedural legitimacy. See generally, for example, Tom R. Tyler, Procedural Justice, Legitimacy, and the Effective Rule of Law, 30 Crime & Just 283 (2003).

- 37Easton, A Systems Analysis of Political Life at 273 (cited in note 36). See also Easton, 5 British J Polit Sci at 444 (cited in note 36).

- 38This distinction is used by most political science accounts on legitimacy. See, for example, Gibson and Caldeira, 39 Am J Polit Sci at 474–76 (cited in note 36); Gregory A. Caldeira and James L. Gibson, The Legitimacy of the Court of Justice in the European Union: Models of Institutional Support, 89 Am Polit Sci Rev 356, 365–67 (1995); Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird, 92 Am Polit Sci Rev at 348–52 (cited in note 36); Yonatan Lupu, International Judicial Legitimacy: Lessons from National Courts, 14 Theoretical Inquiries L 437, 440–45 (2013).

- 39See Gibson, Caldeira, and Baird, 92 Am Polit Sci Rev at 354–55 (cited in note 36).

- 40See Shapiro, 32 Isr L Rev at 11 (cited in note 29) (suggesting that a court that “consistently favors some of the power holders over others” will not be seen as neutral, which might undermine its success).

- 41See Heinz Klug, Constitutional Authority and Judicial Pragmatism: Politics and Law in the Evolution of South Africa’s Constitutional Court, in Kapiszweski, Silverstein, and Kagan, eds, Consequential Courts 93, 109–12 (cited in note 4).

- 42See Fallon, 118 Harv L Rev at 1840–41 (cited in note 36). See also Philip Bobbitt, Constitutional Fate: Theory of the Constitution 5, 234–35 (Oxford 1982) (suggesting different styles of constitutional argument that can improve legitimacy); Shapiro, 32 Isr L Rev at 9 (cited in note 29).